Members of northeast Wisconsin's Hispanic community look forward following a century of struggle and advocacy

Spanish speakers came to Wisconsin before it was a state — here's how they've shaped the economy, labor laws and found the American dream.

Wisconsin Watch

April 6, 2022 • Northeast Region

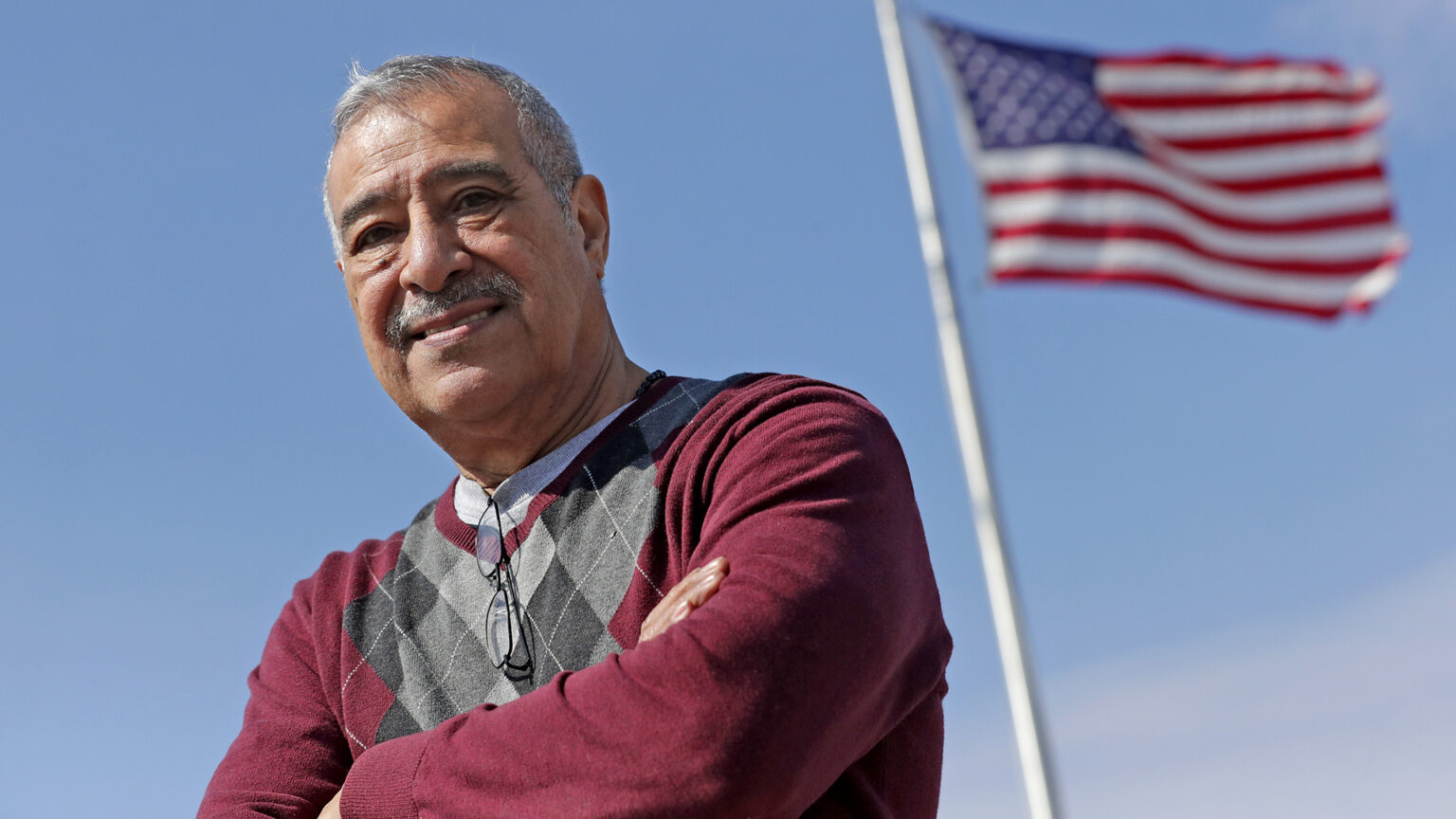

Ernesto Gonzalez Jr. is president of Casa Hispana, a nonprofit in Menasha that serves Hispanic people primarily in the Calumet, Outagamie and Winnebago counties. Gonzales, who spent his early years as migrant farm worker, was among the founders of Casa Hispana. He is shown here on March 16, 2022, in Menasha. (Credit: Dan Powers / Appleton Post-Crescent)

By Ariel Perez and Benita Mathew, Green Bay Press-Gazette

When Carlos Muñoz arrived in the United States in 1973, he was thinking only about vacationing.

Family members who lived in Aurora, Illinois, had been trying to convince him for some time to come to the United States and stay, but he believed he had a good job in Mexico. He did not want to move.

“All my family was here,” he said. “I was the only one living in Mexico, and I had a steady job at the National Bank as an accountant.”

During that visit, his brother-in-law, Esteban de León, who worked as a supervisor at a factory, took him to a shoe store.

Curious, he asked de Leon if he was buying new shoes. No, his brother-in-law answered, “You are. Safety shoes.”

“Why would I need those?” Muñoz asked.

“I want you to work at the factory for a week,” de León told him. “If you like it, you can stay.”

Muñoz worked the job for a week and got paid. Then he worked for another week with a day of overtime pay.

“In Mexico I had a salary-based job. You would work 15 hours and wouldn’t get an extra penny. Here, in two weeks, I made a lot more,” he said. “My perspective changed, I decided to stay.”

From Aurora, he and his family moved to Racine, Wisconsin and then to Oshkosh. At that time, not many Hispanics or Latinos lived in Oshkosh, he said.

“There were like five families, and we all knew each other,” Muñoz said. “Now it’s different. The population has increased considerably.”

Carlos Muñoz Sr. of Fond du Lac, Wis. and his son, Carlos Jr., stand outside Fond du Lac High School on Election Day in 2014, where the father cast his first ballot as an American citizen. (Credit: Fond du Lac Reporter)

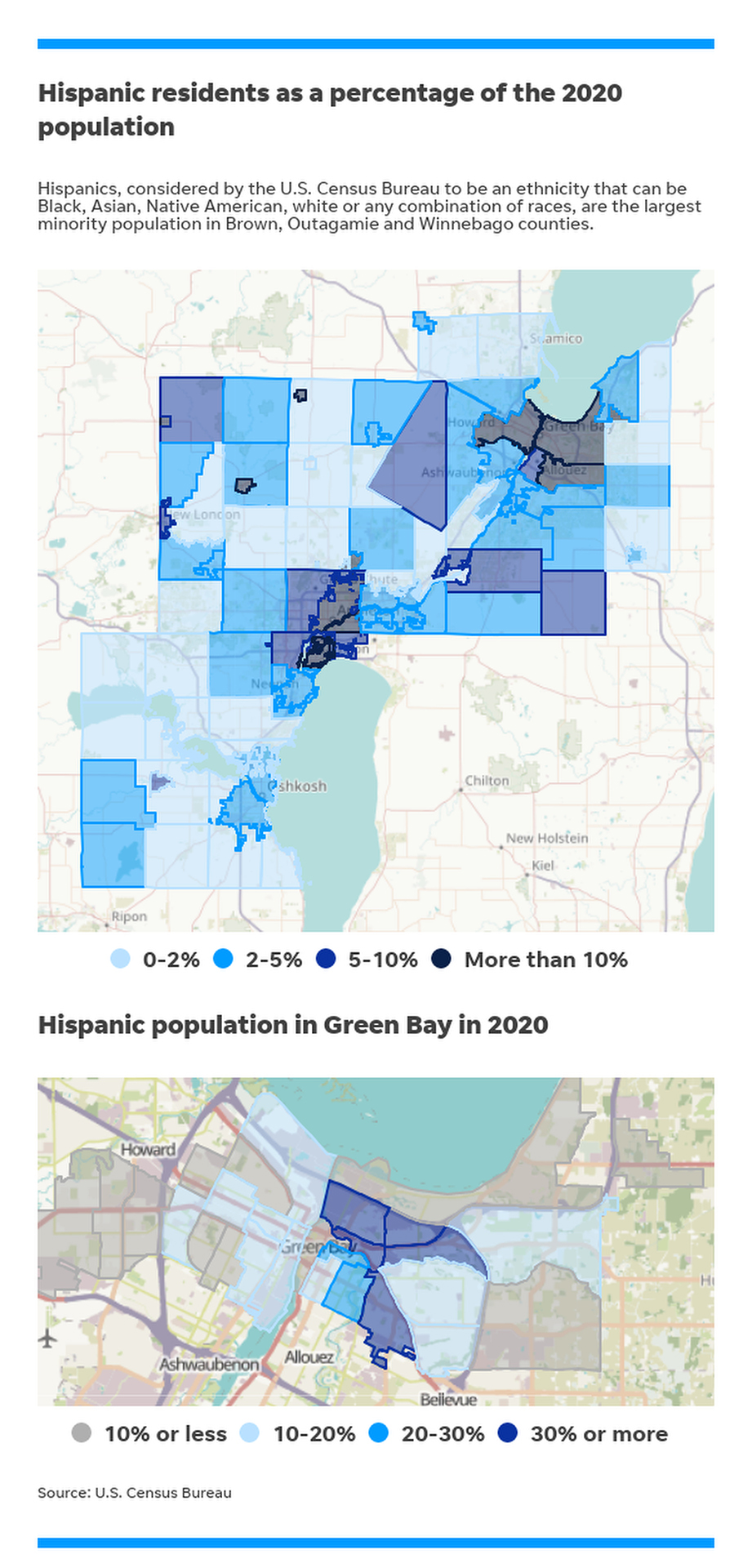

In Oshkosh, the Hispanic population has grown to 3,000 people, or 4.4% of the city’s population. About one-third of those residents moved to the city in the past 10 years, according to the 2020 U.S. Census.

The change in Oshkosh is reflected across northeastern Wisconsin, a place where new Hispanic and Latino arrivals, unlike Muñoz when he moved to Oshkosh, are increasingly able to find established multi-generational communities that offer a support system that eases the move to a new city.

In Green Bay, home to the largest Hispanic population north of Milwaukee, Hispanic people make up more than 40% of the population in the neighborhoods that fall within four census tracts on the city’s east side. Almost one in five Green Bay residents identified as Hispanic in the 2020 census.

Muñoz stayed in northeastern Wisconsin for the same reasons that bring other people to the region: He found security to raise his family and better job opportunities.

After earning a welding license, he worked at Oshkosh Corp. for 35 years before retiring four years ago. In 2014, after moving to Fond du Lac, he became a U.S. citizen and voted for the first time in that year’s November election.

In his spare time, Muñoz focused on building and supporting the region’s Hispanic community. He has, since the early 1990s, organized Mexican celebrations like Cinco de Mayo and nights for Mexican music, dancing and food that draw people from across the region.

There are far more people to reach now than when Muñoz started holding dances in Oshkosh and Omro. More than 45,000 Hispanic and Latino people now live in Brown, Outagamie and Winnebago counties, a number that has increased 45% since 2010.

The U.S. Census Bureau acknowledged in March 2022 that the 2020 census undercounted several groups, including Hispanics, for whom it estimated the census may have missed 5% of the population.

Nonetheless, the census paints a picture of a fast-growing Hispanic population that includes newcomers as well as families that have been here for generations. In fact, the first Hispanic people to come to the state arrived well before Wisconsin achieved statehood.

(USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin)

A long history in Wisconsin

According to historians and articles compiled by the Wisconsin Historical Society, the first Spanish speakers likely arrived in Wisconsin in the late 1700s, when Spain maintained a frontier outpost in St. Louis. Soldiers probably adventured north on the Mississippi and Wisconsin rivers, although such travels are largely unrecorded.

It was in the 1880s when the first prominent Mexican settled in Milwaukee with his family. Accomplished musician and composer, Raphael Baez, became an important personality not just as a musician, but as a teacher, tells Sergio Gonzalez, assistant professor of Latino Studies at Marquette University, in his book “Mexicans in Wisconsin.”

However, there wasn’t a significant migration to Wisconsin until the 1920s, when laws passed in the wake of World War I restricted immigration from southern and eastern Europe.

Corporations and farmers turned to Mexico and the border with Texas to find a new source of low-cost labor.

“Most of them who came here arrived because of work and economic opportunities,” Sergio Gonzalez said.

By the mid-1920s, hundreds of thousands of Mexicans were working in the United States, including several thousand in Wisconsin.

Their numbers declined in the 1930s as work dried up during the Great Depression, but employers again turned to Mexican workers to address a labor shortage as manufacturing and farm production picked up during World War II and men were called to join the military.

A treaty with Mexico in 1942 led to the creation of the Bracero program, a guest-worker program that brought people to the U.S. on short-term work contracts. The program guaranteed fair wages and protection from discrimination, although those requirements were often not honored by employers. By the time the agreement ended in 1964, it had brought more than 4 million workers to the county.

“In the late-1940s, that’s really when the Green Bay area, and the surrounding rural areas, has the first imprint of a Latino population,” Sergio Gonzalez said.

The Bracero (the Spanish word for arms) program ended as farms became increasingly mechanized, but Wisconsin farms and agricultural businesses continued to rely on Hispanic laborers, and the stream of migrant workers coming to Wisconsin remained intact. In Door County, they picked cherries, processed cabbage, beans, cucumbers, potatoes and other crops throughout the state. They tended and harvested Christmas trees.

And Hispanic men and women became a crucial workforce on dairy farms, in canneries and in slaughterhouses.

Meanwhile other Hispanic groups were also arriving in Wisconsin.

According to “Hispanics in Wisconsin: A Bibliography of Resource Materials,” a publication of the Wisconsin Historical Society, Puerto Ricans in the 1950s came to Michigan to harvest field crops.

Between harvests, many of those workers lived in places like Milwaukee and Chicago. Still others migrated to Wisconsin from Lorain, an industrial city in Ohio, which had one of the longest standing permanent population settlements in the Midwest. By 1953, more than 2,500 Puerto Ricans lived in Wisconsin, most of them in Milwaukee.

Cubans arrived in significant numbers in the 1960s after fleeing the revolution that brought Fidel Castro to power. Some of those who fled to Florida were sent temporarily to Fort McCoy and, after screening, moved to Madison, Milwaukee and Green Bay.

“It’s in this period we have the Latino population growing, mostly in southeast Wisconsin, but then you start to see them kind of spread out specifically at the eastern part of the state moving all the way up,” Sergio Gonzalez said.

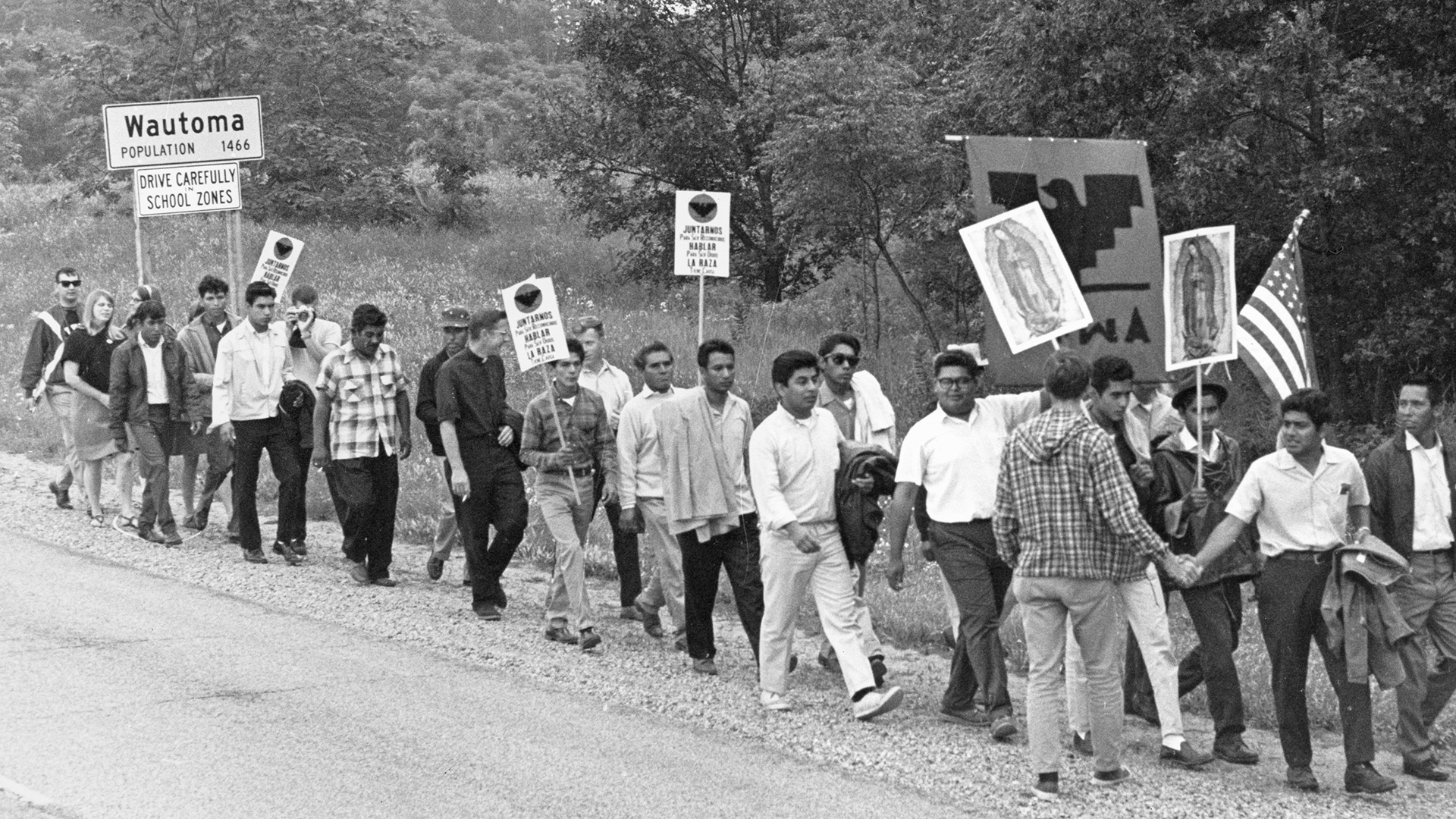

As their numbers increased, Hispanics in Wisconsin also found themselves in a stronger position to fight for better treatment. Jesus Salas, a Texas-born, third-generation American from Wautoma, became a prominent labor organizer for agricultural workers in the 1960s.

Salas’ grandfather had been part of the early wave of migrant workers who each year followed the harvests north, from Texas to Wisconsin and then back south for the winter.

His parents also were migrant workers who, on each year’s journey harvested cucumbers, sugar beets, tomatoes, cotton and other crops. One of his older brothers was born in Wisconsin in 1942.

Salas was born the following year in Texas.

It wasn’t until 1959 that the family decided to settle in Wautoma because Salas’ father wanted his children to finish school and go to college. He and his brother both attended the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh.

He started working with migrants after representatives of the state Department of Children and Families asked him to help start a new child care program for migrant families.

“For the next three years I returned to the labor camps, not to work now, but to recruit children … We grew the day care centers from one center in 1962 to seven of them, serving over 150 children,” he said.

This work sparked his involvement in other efforts to improve working conditions and wages of migrant workers.

At 22, he became a founder of Obreros Unidos, a farmworkers union that organized protests and walkouts at farms and factories across eastern Wisconsin that demanded better pay and improved working conditions.

In 1966, he took the issue to the state Capitol, leading a high-profile march from Wautoma to Madison. His efforts won the support of César Chávez, whose California farmworkers union had risen to national prominence during the Grape Boycott in the mid 1960s.

In 1969, Salas became the executive director of United Migrant Opportunity Services, a Milwaukee-based nonprofit that works to improve employment, education, health and housing opportunities for migrants.

UMOS grew to be a leading force in an effort to encourage workers to leave the migrant stream, settle in Wisconsin and raise their children here. That work to encourage migrants to settle down in places that could provide stable jobs and affordable housing played a significant role in the rapid growth of urban Hispanic populations and the vibrant business communities that have followed.

“We are integral part of the economy of the state of Wisconsin, including Green Bay by the way,” Salas said. “The (Latino) population in Green Bay has increased dramatically, from rural now to urban.”

A man shakes hands with Jesus Salas, founder of Obreros Unidos labor union, during a march from Wautoma to Madison, Wis. to demand better living and working conditions for migrant workers. (Credit: Courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society, WHI-93386)

Gov. Patrick Lucey organized a task force in 1971 to bolster upward mobility among members of the state’s Spanish-speaking communities and more directly address their needs.

This task force held hearings for four days in March of 1971, then turned over a list of recommendations to Lucey regarding education, health and social services, law enforcement and community relations and recreation.

One of the paragraphs in the cover letter read: “We believe the Governor’s office should use its vast moral and political influences to immediate positive results based upon the community needs described in this report.”

The task force’s recommendations provided a starting point, with other efforts by activist groups leading to the bilingual-bicultural education law in 1991, the migrant labor law, and access to a network of social services, Salas said.

“We had the legislative support to affect some of the changes needed at the time,” he said.

From migrant to advocate

Appleton resident Ernesto Gonzalez didn’t plan on moving from Texas to Wisconsin, but he counts himself among those whose lives were changed by the work UMOS did in Wisconsin’s farm fields.

Gonzalez, 70, grew up as a third-generation migrant farm worker. His grandmother and others from his hometown came to Wisconsin in the 1950s each summer to work on crops in Bear Creek. He joined the migrant workforce when he was 18 in 1970.

During the summer, he said, the influx of migrant workers from Texas and Mexico was unmistakable in towns like Shiocton, Wautoma and Plainfield.

“Those towns were majority Hispanic, just for that summer,” he said.

Gonzalez’ older brother, who began working on Wisconsin farms at 15, stayed in Wisconsin after meeting his wife. After Gonzalez finished school in San Antonio and married his wife, his brother urged them to come up for another summer to make enough money to live comfortably in San Antonio. He came, but the latter half of that plan never happened.

“We didn’t make enough money,” Ernesto Gonzalez said. “So, we just stayed, and stayed, and stayed.”

After three years of farm work, Gonzalez was able to stop doing farm work with UMOS’ help.

“They were convincing migrant workers to come work and settle down,” he said. “With a main office in Milwaukee, the United Migrant services was working as far as Sturgeon Bay.”

Eventually Ernesto Gonzalez helped start Casa Hispana, a Menasha-based nonprofit that serves Hispanic people, primarily in Calumet, Outagamie and Winnebago counties.

The organization traces its roots to a scholarship program started by UMOS in 1992. As the Hispanic population grew, Ernesto Gonzalez and other organizers recognized the community needed more services and support.

“We were getting a lot of immigration up north. People from all over were moving in,” Ernesto Gonzalez said. “We gathered some Hispanic leaders, and we started this organization.”

The next generation

Emmanuel Vargas, 19, is the son of Mexican immigrants who came to Green Bay, by way of Ohio, in 2003.

His dad works at the JBS meatpacking plant and his mom at Bay Towel. Vargas’ family lived with his grandparents when he was growing up on Green Bay’s east side. He’s grateful they have always been nearby and able to develop a tight-knit relationship.

“I’m thankful that my parents worked hard to have a roof over our heads, able to work, and to get food and water for me,” he said.

Emmanuel Vargas poses for a portrait at the College of Business building on the campus of Northeast Wisconsin Technical College in Green Bay, Wis., on March 8, 2022. Vargas is studying digital media. (Credit: Samantha Madar / Green Bay Press-Gazette)

That hard work allowed him to live a quintessentially American life, one spent skating downtown, playing soccer in one of the many fields around Green Bay, or finding ways to spruce up his home with his mom.

He also grew up watching vloggers and streamers on YouTube and was curious about how they turned a hobby into a career. Seeing them get paid for recording pranks or playing video games made him realize that he could find a job doing something he loves, while also supporting his family.

“To have that ability and to gain the skills from just watching YouTube videos is helping me to know what’s in store and that anything could happen and nothing’s impossible to do,” he said.

Last fall, he started studying digital media technology at Northeast Wisconsin Technical College in hopes of working in video production, on a movie set or for YouTube.

“To be able to accomplish that childhood dream — it’s God’s work and it would help out tremendously with my family, me and my life situations,” Vargas said.

Ariel Perez is a business reporter for the Green Bay Press-Gazette. You can reach him at [email protected] or view his Twitter profile at @Ariel_Perez85. Contact Benita Mathew at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter at @benita_mathew.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us