Meet the high school students keeping Pulaski from becoming a news desert

Pulaski News is a fixture of one community in northeast Wisconsin, a tool to prepare high school students for the workforce and the last official source keeping residents informed about hyperlocal happenings.

Wisconsin Watch

October 27, 2025 • Northeast Region

A stack of copies of the Pulaski News are for sale at Vern's Do It Best Hardware, Rental and Lumber on Aug. 12, 2025, in Pulaski in northeast Wisconsin. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

This story was produced and originally published by Wisconsin Watch, a nonprofit, nonpartisan newsroom.

“The most important sentence in any article is the first one. If it doesn’t introduce the reader to proceed to the second sentence, your article is dead.”

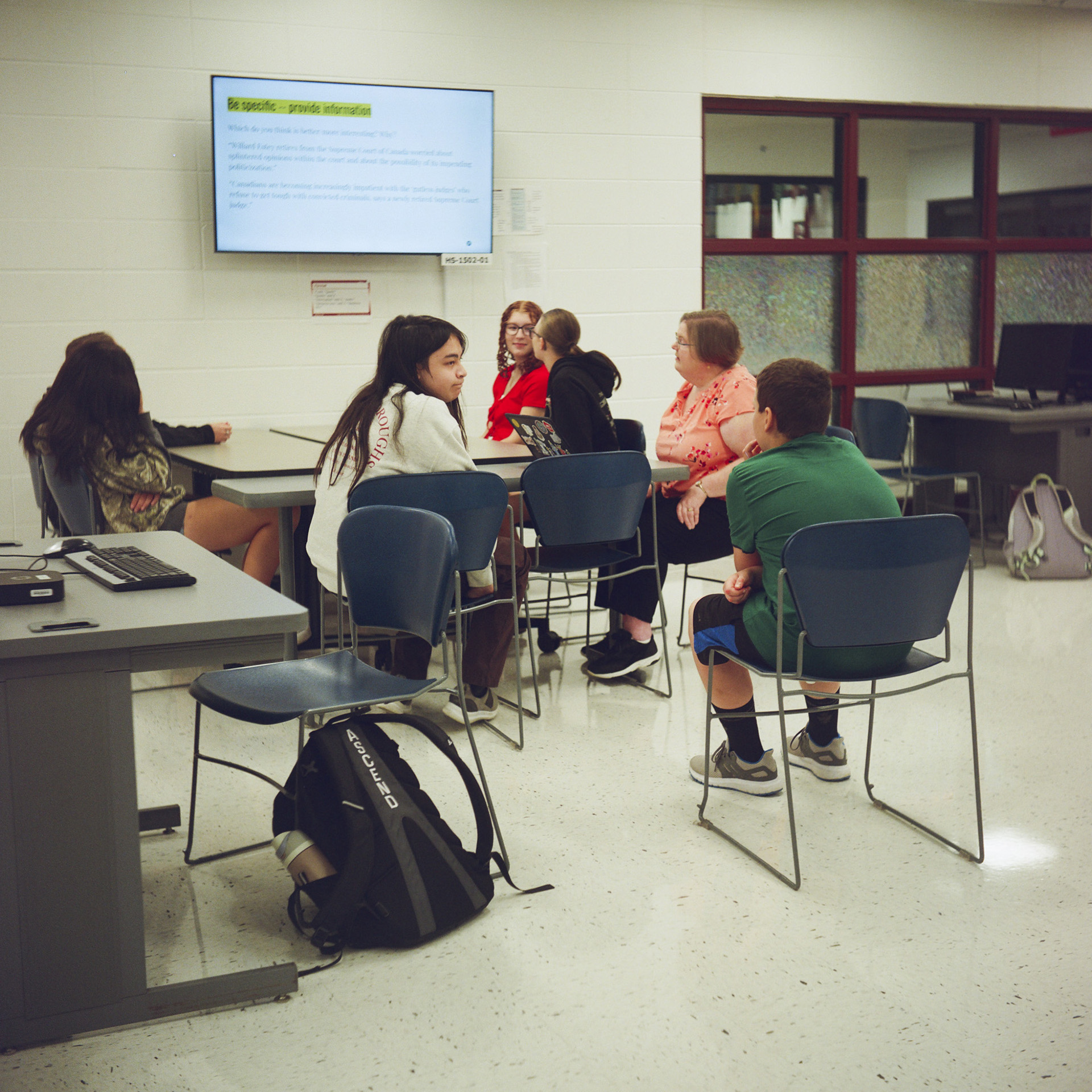

Three weeks into the school year at Pulaski High School, six teenagers sit around a cluster of desks, listening intently as journalism instructor Amy Tubbs taught them the mechanics of writing a news story.

While Tubbs knows it might sound harsh, the task of hooking readers carries weight for the students. For more than eight decades, Pulaski High School’s student newspaper has been the community’s newspaper of record, as the only news outlet consistently covering the rural village.

As local news has dwindled across the country, Pulaski News has become a fixture of the community, a tool to prepare students for the workforce and the last official source keeping residents informed about hyperlocal happenings.

A sign marks the temperature, date and time outside Pulaski High School on Sept. 16, 2025, in Pulaski. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Through routine practice with writing, interviewing, photography and media literacy, the teenagers secure skills that prepare them for life after high school. Students say working for the paper helps them feel closer to their northeast Wisconsin community.

“I joined last year because I really love writing, and I saw this as an opportunity to get to do that,” sophomore Dellah Hall said. “I’m now able to write not just for school and grades, but this is for the community.”

Along the way, the paper has secured a level of community buy-in that might feel foreign to some news organizations today, as trust in news declines. Students nurture this by regularly sharing feel-good stories.

Students listen to a lesson about how to write a news story lede on Sept. 16, 2025, at Pulaski High School in Pulaski. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

For example, freshman Neville Nguyen is writing a profile on a well-known “legend of Pulaski”: an 84-year-old woman who runs the local McDonald’s drive-through every morning. Nguyen’s article is going to be published in the Pulaski News‘ Thanksgiving edition, an annual feature that highlights someone who has something for which to be thankful.

“Its own kind of niche … That’s not necessarily something that a bigger paper is going to pick up … There’s definitely very much a hometown kind of feel to it,” Tubbs said.

‘Pulaski needs a newspaper’

Roughly 20 miles outside of Green Bay, the village of Pulaski sits amid an expanse of farmland. The modest 3,700-person town straddles Brown, Oconto and Shawano counties.

The area has a turbulent history with local news. Residents saw a flurry of different papers stumbling to provide the headlines before Pulaski High School took the reins in the 1940s.

During the 1920s, residents relied on the Pulaski Herald. Archives of the Herald are sparse, but they show it ceased publication by the 1930s, when a resident launched the Pulaski Tri-Copa. In 1939, the Tri-Copa abruptly announced it would be rebranding, ambiguously citing “skirmishes” over the previous year.

“We don’t care to divulge what we have up our sleeve at this time,” the Tri-Copa‘s farewell edition read. “It will be more pleasant to surprise you, but take our word for it, you are going to get more paper for your money.”

Two months later, the paper restarted as the Tri County News. It ran for three years before folding due to financial issues brought on by the Great Depression.

Leaders at Pulaski High School saw an opportunity for their student newspaper, which was roughly four years old, to fill the gap left by the Tri County‘s closure. Ahead of the 1942-43 school year, the paper debuted a new title: The Pulaski News.

The first edition of the rebranded “Pulaski News” was published on Aug. 12, 1942.

“Pulaski needs a newspaper,” the first edition read. “To fill that need; to provide a means of informing the parents and community on the progress of the school; to provide the community proper channels for information, news, and advertising; and give students experience in journalism the Pulaski Board of Education authorized the publishing of a newspaper.”

When Pulaski News began publishing, it was tabloid-sized. A team of students handled the enterprise’s business aspects, including selling ads across the community.

Today, 83 years’ worth of newspapers — including those early editions — live on a classroom shelf in dozens of hardcover books. In its current iteration, the paper is lengthier and printed in color, but the model remains largely the same.

“Pulaski News” archives are stacked on shelves along the wall in a classroom at Pulaski High School on Aug. 12, 2025, in Pulaski. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Although Pulaski’s students fit within a nationwide demographic that consumes much of their news online, the writers still find appeal in the print product’s legacy. Senior Madelyn Rybak said that while she reads the majority of her news online on her phone, writing for Pulaski News makes her want to consume more print stories. Her parents subscribe to the Green Bay Press-Gazette‘s print edition, which she reads.

“I like the feeling of holding the newspaper,” Rybak said. “It kind of feels like I’m more connected to the stories… instead of just being behind my phone.”

A ‘valuable service’

At the front of the Pulaski News‘ classroom, a calendar governing the paper is posted on the whiteboard: Students turn in stories one week before the paper is sent to press every other Tuesday. It’s printed on Wednesdays and delivered on Thursdays. The school mails roughly 1,000 copies to subscribers, who pay $30 or $35 annually. Eight local businesses sell another 100 copies for $1 each.

Each semester, roughly a dozen students work on the paper for class credit. Course enrollment is fueled largely by word-of-mouth between friends or parents encouraging their teenagers to follow in their footsteps. In the summer, students vie for five part-time positions that pay $11 per hour.

The operation has felt increasingly crucial as Pulaski feels the national trend of thinning local news coverage.

Nearby papers once covered Pulaski more closely than they do today. Now, regional news outlets sometimes drop in for flashier stories, such as crime issues, but there’s no source of consistent information about local events beyond what the students publish.

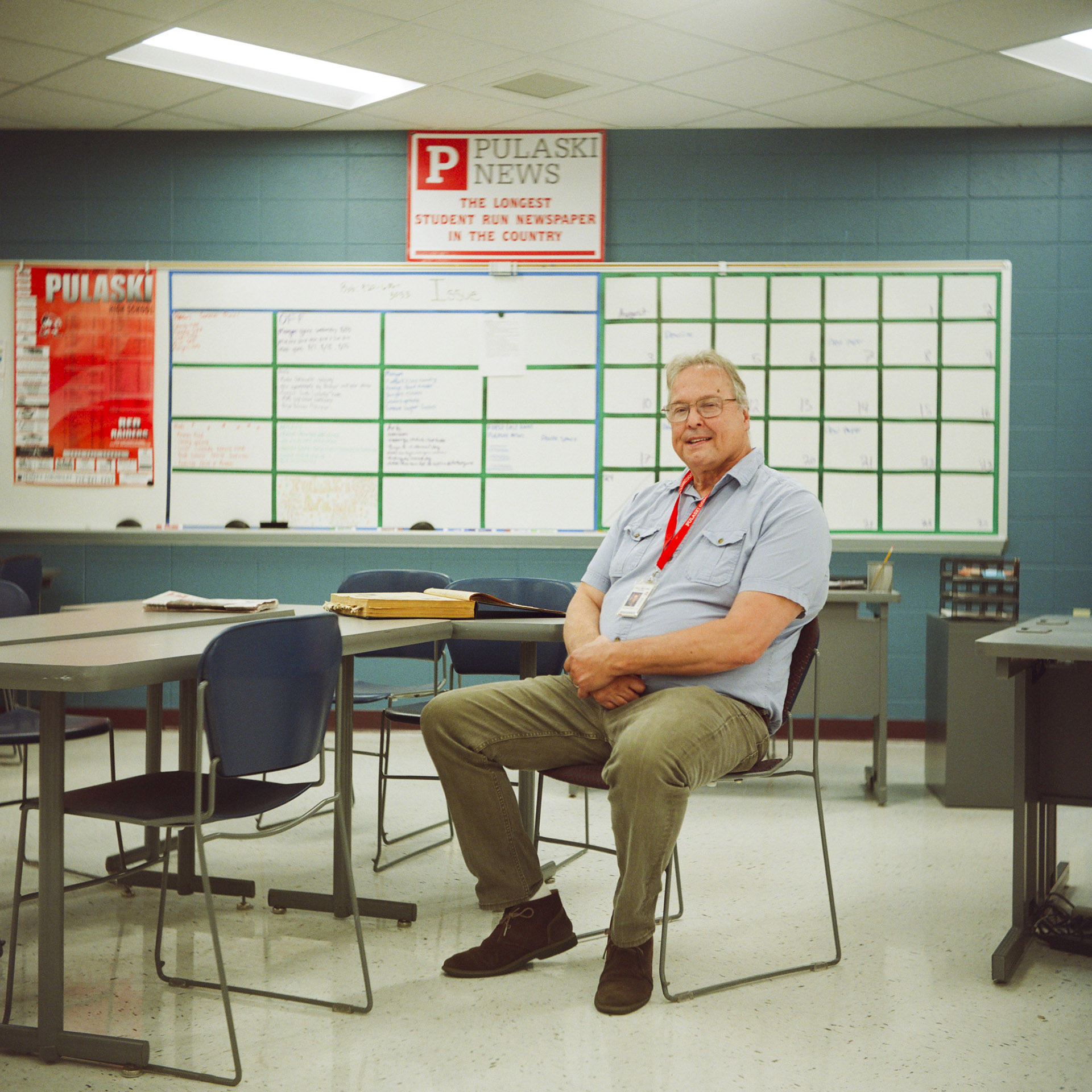

“You’ve seen other local papers close and their communities really don’t have anything,” said Bob Van Enkenvoort, the school district’s communications coordinator and the paper’s editor. “So the district sees this as a valuable community service.”

Though the students fill a hyperlocal information gap, relying on a school-sponsored paper means the town still lacks independent, critical coverage — like an increasing number of places across the U.S.

“It doesn’t really have a good feel for political issues in town, so the community is not all that well served, as far as coverage of local village issues like the village board meetings or growth in the village, so that’s sort of a negative,” said Steve Peplinski, a local resident creating a digital archive of Pulaski’s newspapers for the village’s museum. Peplinski wrote for Pulaski News himself when he was in high school.

- Steve Peplinski carries a box of archived editions of the “Pulaski News” through the attic of the Pulaski Area Historical Society on Aug. 12, 2025, in Pulaski. Peplinski worked for the “Pulaski News” as a reporter between 1965-67. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

- Steve Peplinski looks through a box of archived editions of the Pulaski News through the attic of the Pulaski Area Historical Society on Aug. 12, 2025, in Pulaski. Peplinski works as the secretary of the Pulaski Area Historical Society where he took it upon himself to digitize every issue of the newspaper’s long history. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

While the school district’s administration doesn’t decide what Pulaski News covers — “I’ve never really had anyone say ‘you can’t do this’ or ‘you can do this.’ That’s my decision,” Van Enkenvoort said — the staff generally doesn’t wade into hard news.

Outside of the routine sports, local events and school news, the staff has carved out a niche creating more “positive stories”: They profile interesting community members and spotlight Pulaski alumni doing good deeds.

While some might have trepidation when it comes to speaking with journalists, that “hometown” feel of the paper has resulted in a deep trust among local residents.

“It’s well known in the community,” Van Enkenvoort said. “People understand what the mission is, so I think they are willing to work with the students.”

Bob Van Enkenvoort, Pulaski Community School District’s communications coordinator and “Pulaski News” editor, poses for a portrait during the newspaper’s summer session at Pulaski High School on Aug. 12, 2025, in Pulaski. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Though Pulaski News is district-funded, the paper isn’t immune to the turbulence plaguing journalism today. The subscriber base skews older, and every obituary that publishes is a possible patron, Van Enkenvoort said.

Securing soft skills

The first time Morgan Stewart, a 15-year-old sophomore, picked up the phone to call a subject for her story, she was so terrified that she shook. But over time, those nerves dissipated, and she’s found herself growing into more of a “people person.”

“I think I want to pursue doing journalism,” Stewart said. “I didn’t have much of a plan coming into high school, but after doing this … (Van Enkenvoort) has helped me a lot to find what I love most about Pulaski News, and it’s opened my eyes a lot to the future and what it holds for me.”

- Morgan Stewart, a 15-year-old sophomore, poses for a portrait while working on the summer edition of the “Pulaski News” at Pulaski High School on Aug. 12, 2025, in Pulaski. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

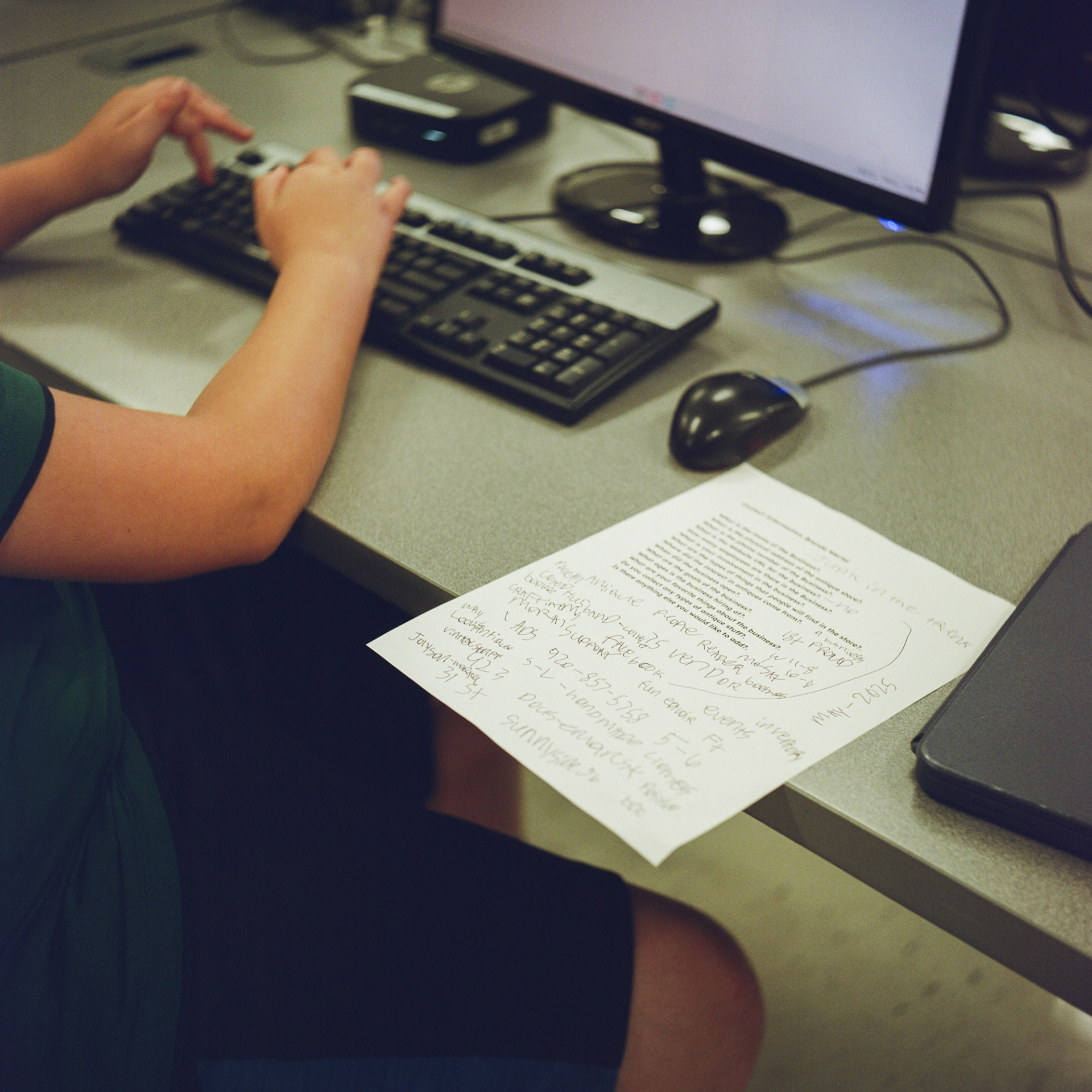

- Neville Nguyen, a freshman, works on a “Pulaski News” story at Pulaski High School on Sept. 16, 2025, in Pulaski. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

There’s always a learning curve at the start of a semester. Students are typically scared to make cold calls. They sometimes try to text community members, only to realize they’re messaging a landline. For their first class assignment, students write profiles about one another to practice asking good questions.

With a few notable exceptions, many students who participate in the Pulaski News aren’t planning to go into the journalism field. But through the routine — and sometimes uncomfortable — work, they learn many “soft skills,” or traits that allow them to communicate and work well with others, Tubbs and Van Enkenvoort said.

- Dellah Hall, a sophomore, works on a “Pulaski News” story at Pulaski High School on Sept. 16, 2025, in Pulaski. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

- Amelia Lytie, a sophomore, poses for a portrait while checking out a camera to use for a “Pulaski News” story at Pulaski High School on Sept. 16, 2025, in Pulaski. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

“We tend to try to get them away from their phones and talk to people face-to-face, so they get used to talking to adults and having to think on their feet and have conversations, which will help them when they’re interviewing for colleges or interviewing for jobs,” Van Enkenvoort said. “A lot of them are just not that comfortable with it at the start, but they get better and they feel more comfortable once they do.”

On paper, the experience allows Pulaski students to complete a class that the state considers “post-secondary preparation,” or training for life after high school. In the 2023-24 school year, 39% of Pulaski High School students participated in a “work-based learning program” like Pulaski News, far above the state average of 9%.

Connecting students to community

While stories on sports games and district updates are commonplace in Pulaski News, students also devise the creative stories that fill the paper. In the process, many become more closely engrained in their community.

Rybak is from Hobart, a roughly 20-minute drive from Pulaski, so she isn’t as familiar with the area as some of her classmates. Working for the paper has helped change that. When there’s pressure to come up with a story pitch, she finds herself scouring the internet and local organizations’ websites for events.

Madelyn Rybak, a 17-year-old senior at Pulaski High School, works on the summer edition of the “Pulaski News” on Aug. 12, 2025, in Pulaski. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

“We encourage the students to try to come up with story ideas for two reasons,” Van Enkenvoort said. “We need everybody’s eyes and ears out in the community. But also, if they come up with a story and they’re excited about it, they typically do a really good job on it.”

At the end of the year, Tubbs asks students to share their favorite stories. Without fail, it’s always the ones centering community members.

- Daniel Roggenbauer, a freshman, works on a “Pulaski News” story at Pulaski High School on Sept. 16, 2025, in Pulaski. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

- Three of the six students working on the “Pulaski News” sit around a table at Pulaski High School on Sept. 16, 2025, in Pulaski. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

That’s true for Rybak, whose standout story in the 2024-25 school year was a front-page feature on Pulaski’s summer school program. She interviewed four teachers, the program director and students who attended classes.

“Our summer school doesn’t really get recognition, even though there’s a lot that goes into it,” Rybak said. “I kind of liked the feeling that I was shining a light on the people who do a lot of work in our community.”

“(The paper) makes me more aware of what’s going on in the community,” she said. “Through interviewing people who I would literally never talk to otherwise, it just helps me get to know the people there that I wouldn’t have known.”

This story is part of Public Square, an occasional photography series highlighting how Wisconsin residents connect with their communities. To suggest someone in your community for Wisconsin Watch to feature, email Joe Timmerman at [email protected].

Miranda Dunlap reports on pathways to success in northeast Wisconsin, working in partnership with Open Campus.

This story was produced as part of the NEW (Northeast Wisconsin) News Lab, a consortium of six news outlets.

![]()

Passport

Passport

Follow Us