Investigating The Enigma Of Lingering Mercury In The U.P.

Mercury levels remain high in the lakes, rivers and fish of the western part of Michigan's Upper Peninsula despite a substantial decline in airborne mercury emissions over the past 30 years.

September 11, 2018

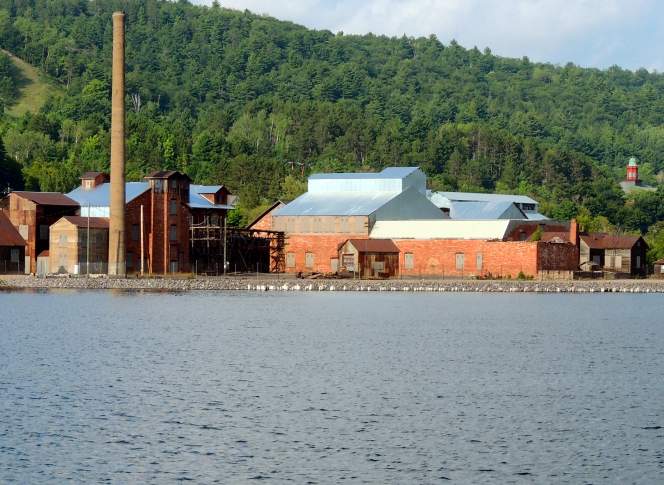

Quincy Smelting Works in Ripley, Michigan

Mercury levels remain high in the lakes, rivers and fish of the western part of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula despite a substantial decline in airborne mercury emissions over the past 30 years, according to scientists from Michigan Technological University and the Environmental Protection Agency.

That’s a “geographic enigma” with health implications, they said in a study published in the March 2018 issue of the journal Environmental Science Processes & Impacts.

The region’s extensive – and growing – wetlands play a major role in the problem. Wetlands are recovering because, as the study observed, “Recently, forested and wetland environments are returning as large northern tracts are converted to state and federal forests and wetland ditching is reduced.”

“We have tried to emphasize the effect of mining superimposed on wetland environments. It’s mining impacts on top of wetland dynamics. That’s important,” said lead author Charles Kerfoot, a biologist and geologist at Michigan Tech.

Mercury emissions in the Lake Superior Basin of Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin have dropped significantly over the past three decades, principally due to a drop in silver, copper, zinc, gold and iron mining and related operations such as smelting, the scientists reported.

People are most often exposed to methylmercury from eating fish and shellfish with high levels of the neurotoxin in their tissues, the EPA says. Among the symptoms are lost peripheral vision, poor coordination, muscle weakness, and impaired hearing and speech.

The hazard isn’t limited to the Great Lakes Basin. “Mercury contamination of the environment from human activity continues to be a global problem,” the study reported.

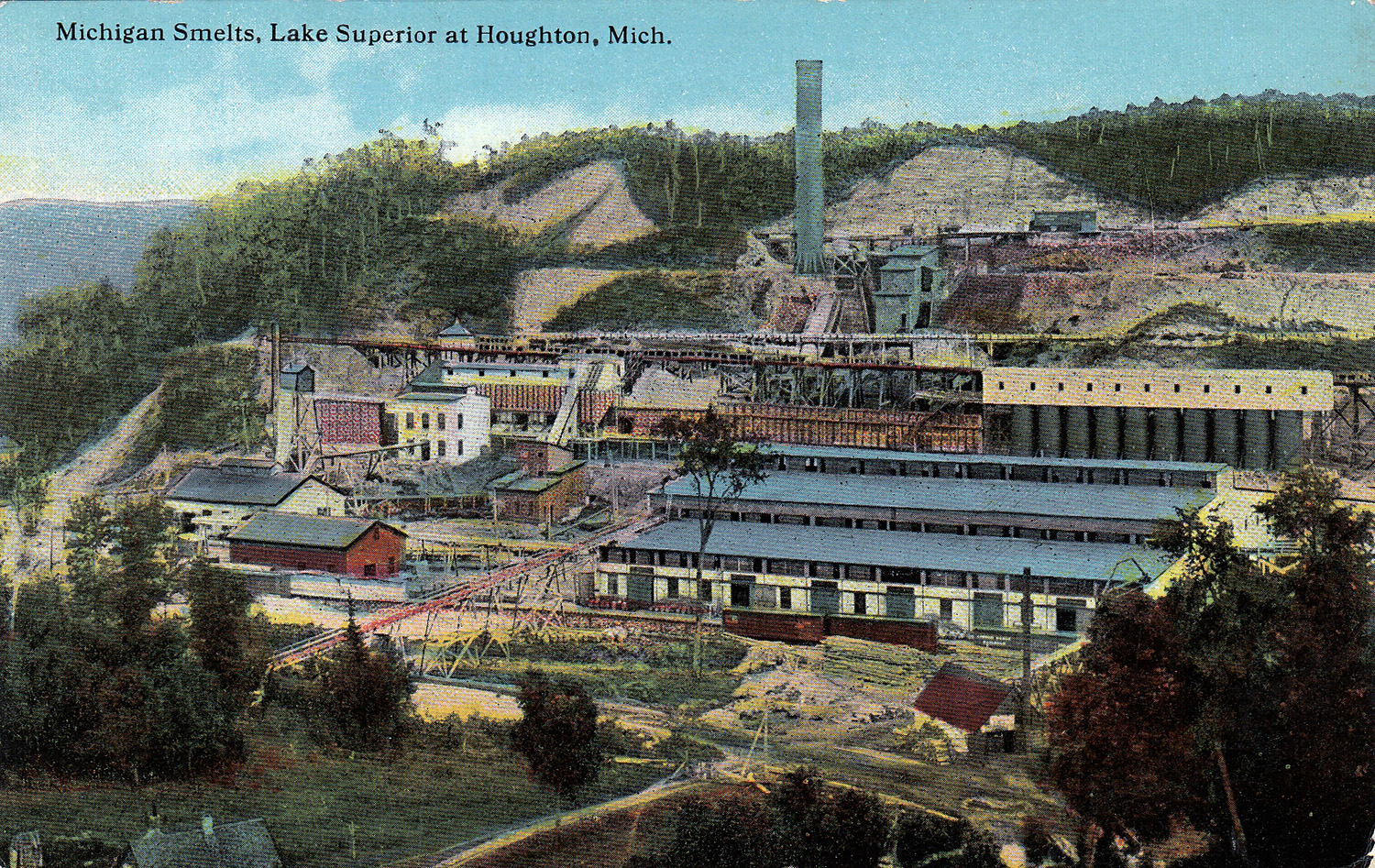

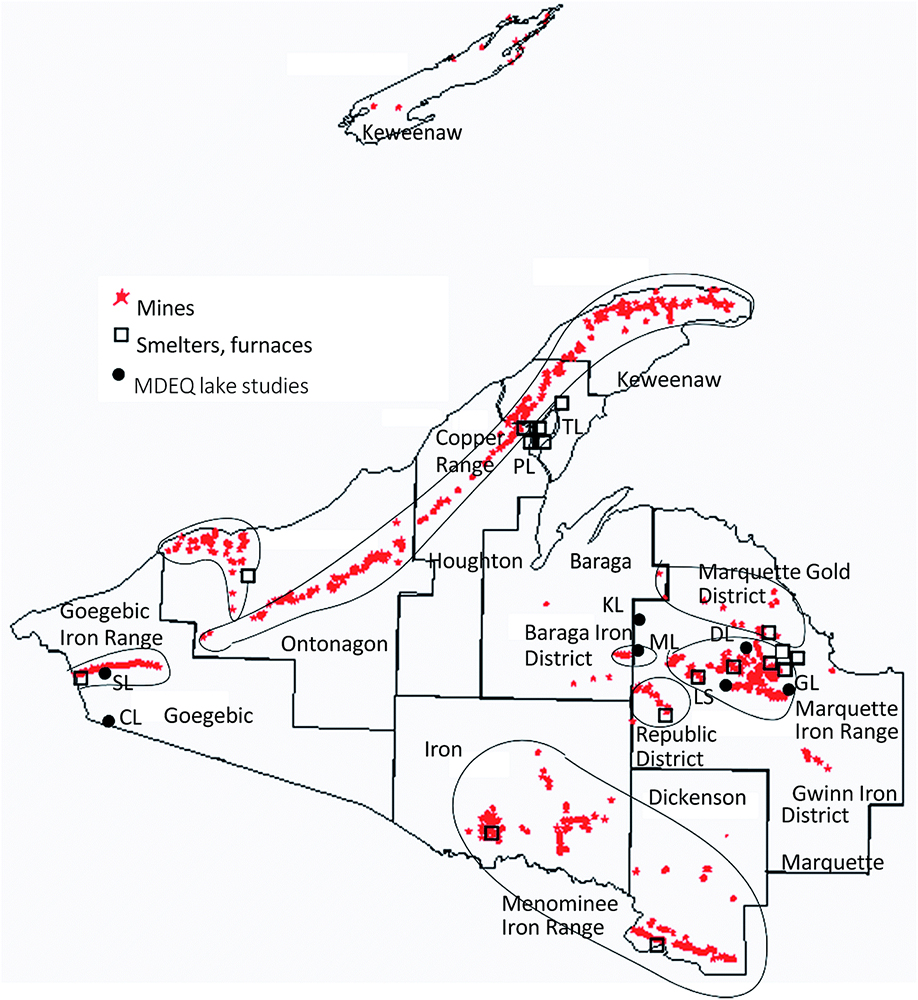

Researchers looked at the “pervasive influence of mining” for a century and half in the Western U.P. That included five smelters and more than 140 native copper mining sites along the mid-rib of the Keweenaw Peninsula, as well as silver and copper mines and a smelter in the Porcupine Copper-Silver District. There also were hundreds of sites in the Baraga, Republic, Marquette, Gwinn and Menominee iron ranges, including about 30 pig iron furnaces in the late 1800s and, more recently, processing of taconite pellets – all emitting mercury.

“Smelter sites are emerging as some of the most contaminated sites,” Kerfoot said. And the study noted that smelters “broadcast mercury over the entire Keweenaw landscape.”

That smelting output, combined with mining emissions, continued “with only brief interruptions” for 140 years, noted the study: “The entire region was industrially active for over a century, economically rivaling downstate.”

Even with the closure of most U.P. mines and smelters, mining remains the source of more than 60 percent of current mercury emissions in the basin, the study reported: “It is clear that legacy mining continues to release mercury into surface waters in the copper mining region of the Keweenaw Peninsula.” Tailings, drainage and piles from mining shafts continue to leach mercury into rivers and streams, and spread mercury over the region’s watersheds.

The increase of wetlands is a major contributor to the problem because mercury can accumulate in them in higher concentrations and for longer periods.

The study noted, “One of the worst landscapes for mining mercury releases is into a wetland environment.” It identified five problem areas in the Lake Superior Basin in particular: the U.P., northeast Minnesota and Ontario’s Thunder Bay, Nipigon and Wawa regions.

In addition to mining, there are other sources of mercury in the region, including emissions from outcrops of natural bedrock.

“We can make a really good case and we answer why there is more residual mercury in the rivers, in the lakes and in the region,” Kerfoot said. “It was in the rocks to begin with and it was mined and released. It’s got the mining components superimposed on wetland environments and in many cases recovering forest.”

Many forests in the area had been devastated. Trees were cut to fuel the mines and smelters, for mining shaft support, or construction and to make paper. Woods were burned to clear land, and wildfires raged.

“The forests are really amazing in terms of their recovery in areas where there has been intensive mining that deforested it,” Kerfoot said. “Along with forest recovery is wetlands recovery.”

As the study observed, “Recently, forested and wetland environments are returning as large northern tracts are converted to state and federal forests and wetland ditching is reduced.”

In addition, Kerfoot said modern mining operations in the U.P. and northern Wisconsin are much more environmentally aware than in the past, with small footprints, placing tailings back into the mines rather than in piles and trying to leave “the least ecosystem impacts.”

As for fish, the researchers noted that there are higher mercury levels in fish from the western U.P. than in those from northern Lower Peninsula watersheds, including bass, walleye and northern pike. “Our studies underscore that the potential risk to human health created by high mercury levels in inland Great Lakes fish is serious,” the report noted.

Additional fish-related research is underway, according to Kerfoot.

For example, Native American tribes in northern Wisconsin are testing fish in 40 lakes used by both their members and the general public. The project intends to sample at least 100 fish from each to identify which lakes and species have the lowest levels of mercury. The information then will be used to provide fish consumption advice, especially for consumers those who are especially vulnerable to adverse health effects of mercury, such as pregnant women.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published on September 4, 2018 by Great Lakes Echo, which covers issues related to the environment of the Great Lakes watershed and is produced by the Knight Center for Environmental Journalism at Michigan State University.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us