In search for ineligible Wisconsin voters, activists uncover gaps — but no plot

Elections officials agree the system to track 'incompetent' voters needs fixing, but claims by conservative groups of thousands of people who have lost voting rights but cast ballots in Wisconsin are overblown.

Wisconsin Watch

October 12, 2022

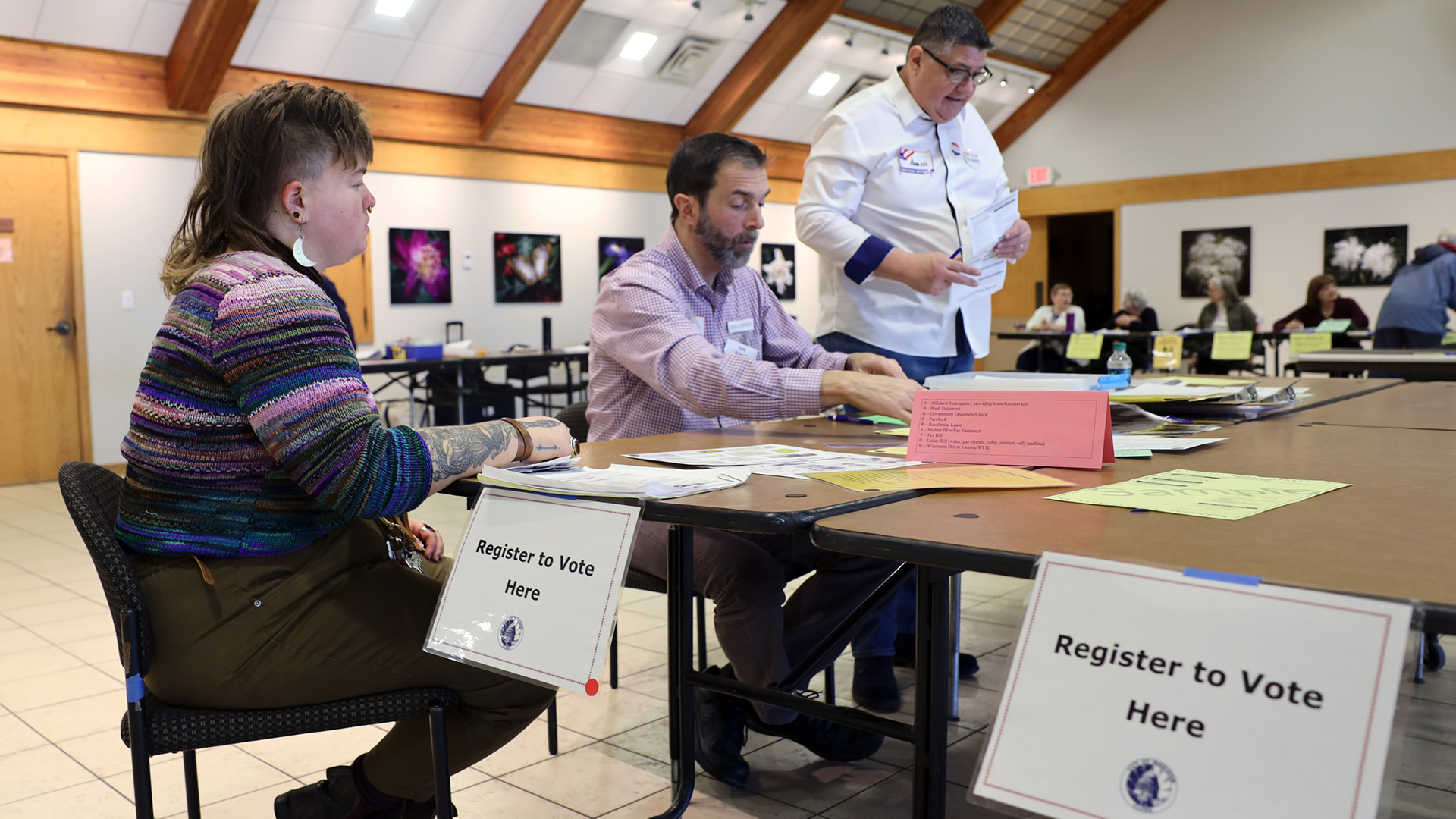

Voting signs are seen outside the polling place at the Catholic Multicultural Center in Madison on Nov. 3, 2020. Conservative activists say holes in the state's voter database have allowed some ineligible voters to cast a ballot. But their efforts also have conflated ineligible and eligible voters and spread misleading information, Wisconsin Watch found. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

Conservative activists are pushing officials to remove thousands of people from Wisconsin’s voter rolls, pointing to holes in the state’s voter database that have allowed some ineligible voters to cast a ballot.

But their efforts also have spread misleading information, Wisconsin Watch found, conflating ineligible and eligible voters and sowing doubts about the upcoming election during a volatile time for American democracy.

Such efforts aren’t unique to Wisconsin. The New York Times reported on attempts in Georgia, Michigan and Texas to have tens of thousands of people removed from voter rolls. The newspaper reported the effort — which includes instructions from an influential think tank with close ties to former President Donald Trump — aims to flood election offices with challenges that are costly and time-consuming.

The activist groups include the Thomas More Society and Wisconsin Voter Alliance, whose members challenged the 2020 election results and worked on the more than $1 million taxpayer-funded 2020 election investigation that Republican Assembly Speaker Robin Vos shut down in August.

Another effort targeting thousands of voters who might have changed addresses is underway by a group run by Peter Bernegger, who previously filed numerous complaints with the Wisconsin Elections Commission that it deemed “frivolous.”

On Sept. 27, Wisconsin Voter Alliance president Ron Heuer, who worked on the 2020 election investigation, warned local clerks that their systems are vulnerable because, by his estimate, there are potentially thousands of people under court-ordered guardianships whose votes could be fraudulently manipulated. He pointed to the case of an Outagamie County nursing home resident who voted in 2020, even though a court had ruled she was “incompetent” to vote months earlier.

Officials acknowledge gaps

A Wisconsin Watch investigation has found a yet-to-be-determined number of Wisconsinites whom a court has deemed incompetent to vote are still listed as active voters — and actually cast ballots in past elections.

Dane County Clerk Scott McDonell said he is reviewing the 1,013 ineligible voters in Dane County deemed incompetent after a sample of 20 included two who were still listed as active in the Wisconsin Elections Commission’s voter files — one of whom voted while ineligible in April 2019.

“We’re going to review our data and make sure it’s accurate,” McDonell told Wisconsin Watch.

The total number, although unknown, is likely too small to have affected the results of the 2020 election, in which 3.2 million cast ballots in Wisconsin.

It is certainly less than Heuer’s claim because in his warning to the state’s 1,800 clerks, he conflated people under a court-ordered guardianship, many of whom can vote, with the much smaller subset of those who have lost voting rights. And the Outagamie case — while indeed an example of someone who shouldn’t have been able to vote in 2020 — shows how administrative error is the most likely reason these ineligible voters cast ballots.

Heuer’s work has already prompted public officials to take action. On Oct. 3, the Wisconsin Elections Commission issued a guide to local election clerks warning they cannot purge voters unless they find “beyond a reasonable doubt” a voter is ineligible. “Inactivating a record based solely on the allegations of a private party,” the agency wrote, “is unwise and may violate the law.”

WEC spokesman Riley Vetterkind acknowledged to Wisconsin Watch the system for tracking incompetent voters could be improved, although it would require a legislative fix to ensure they are tracked the same way as other ineligible voters, such as felons still serving a sentence.

The WEC also has changed its voter data so that the public can’t see the names and addresses of those who have been identified as “incompetent” — data that state law requires court officials to keep private. WEC made the change in August after it released that data to Heuer, who used it to build his case that thousands of ineligible voters could still be on the voting rolls.

Heuer’s group is now suing the court officials who handle guardianship records in 13 counties to access the names and addresses of everyone placed under a court-ordered guardianship. The group’s earlier requests for those records were denied. Heuer said their goal is to determine the true number of ineligible voters who have cast ballots.

The push to purge names from the voter rolls — from Heuer, Bernegger and others — is the latest front by partisan activists who have relentlessly challenged the validity of the 2020 election and now may be trying to create grounds to dispute future election results, according to David Becker, a non-voting board member of the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC), which Wisconsin and 32 other states — run by Republicans and Democrats — use to maintain their voter rolls.

Research finds little fraud

Think tanks on the left and right agree there is little fraud in U.S. elections. The conservative Heritage Foundation tracks “proven” cases of electoral fraud nationwide. By its numbers — which it says are not comprehensive — there were four instances of fraud in Wisconsin in 2020: two of them controversial prosecutions in Fond du Lac County where voters had listed a UPS store where they get their mail as a physical address. Experts have described some of these instances as incorrect votes and not fraud because the voters didn’t know their registration was improper.

Election watchdogs say the specter of systemic corruption at the polls is dangerous because it undercuts the public’s faith in democracy.

“Widespread fraud does not exist,” said Lauren Miller, a lawyer with the liberal Brennan Center for Justice that tracks elections. “It’s always a serious concern when people believe the lie that their elections are rigged.”

Becker said age-old attempts to “artificially inflate” voter list accuracy bring more risks in the current climate.

“When we get to the point where we can’t accept that our side has lost an election, the next natural step is political violence,” Becker said. “And that is not a hypothetical. We have already seen this. When tensions get as high as they are, when grifters have been incentivized to keep the anger going to keep donations flowing in, then you get a very, very dangerous situation.”

Number of incompetent voters disputed

The activists presented their information about incompetent voters to an Assembly committee, which then pressed the Elections Commission on the matter. On Sept. 22, the WEC responded to the Legislature saying it had already begun an independent audit of its voter roll data related to voters deemed incompetent and is working with court officials to “improve the reporting and inactivation” of such records.

Ron Heuer, president of the Wisconsin Voter Alliance, spoke at a Thomas More Society fundraiser in Okauchee on Sept. 29. 2022 about his efforts to investigate the 2020 election. He is leading the group’s investigation into alleged “elder voting abuse.” (Credit: Matthew DeFour / Wisconsin Watch)

On Sept. 27, Heuer warned the state’s more than 1,800 clerks that there are some 15,000 Wisconsin residents under a court-ordered guardianship, but fewer than 1,200 listed in WEC’s voter roll file as incompetent. Heuer concluded the true number of incompetent voters is underreported and thus the whole system is vulnerable to “elder voting abuse.”

But the information he cited was misleading.

The voter roll data file is a constantly updated public record with voter names and addresses that anyone in the public can obtain for $12,500. Heuer obtained a version of the file with about 1,200 names and addresses of voters listed as “ineligible” and the reason “incompetent.”

When Heuer broke down the list by county, he found several counties had zero ineligible voters listed as incompetent. When he shared that information with county court officials, several told him that there were far more people adjudicated incompetent to vote in their county than were listed in the WEC database.

“It really caused a tizzy,” Heuer said.

He then requested guardianship numbers in each county between 2016 and 2021. Based on responses from about a third of the state’s district courts — and using a per capita projection — he came up with the 15,000 estimate.

However, the numbers Heuer used include everyone placed under a guardianship — even though not all of them have lost their right to vote. Also some are deceased — and some may never have been registered to vote — so they wouldn’t appear in the public voter roll file. And some people placed under a guardianship and deemed ineligible years ago may have had their right to vote restored.

WEC keeps incompetent voter data in a non-public file that is accessible to local clerks, who must review it periodically to update the registration status of voters, Vetterkind said.

“It is possible you may find voters who, despite being adjudicated incompetent by a court, registered, continue to be registered, or voted in an election(s),” Vetterkind said, although he declined to estimate how many. “These cases are unfortunately a product of the limitations that state law currently places on the process for centrally compiling adjudicated incompetent records.”

Guardianship numbers parsed

Dane County Clerk of Courts Carlo Esqueda, who is also the county’s register in probate, told Heuer in an August email that there were 1,004 people in Dane County placed under guardianship between 2016 and 2021. But he also warned him that he shouldn’t conflate guardianship numbers with the much smaller subset of incompetent voters. Heuer never asked for the smaller list.

Esqueda told Wisconsin Watch that after removing deceased voters and those who can still legally vote, the number of incompetent voters shrank to 281.

“I have told Mr. Heuer that, as have several of my colleagues, and he refuses to back off at least the strong implication that guardianship equals the loss of the right to vote,” Esqueda said.

Responded Heuer: “In future communications we will be refining our numbers as information becomes available. When we get the info, we will share it with the public.”

McDonell told Wisconsin Watch there are 1,013 people from Dane County listed as incompetent in the WEC’s files since 2007, including 75 marked in the voter file as inactive. In the sample of 20, he found eight had never registered, one was inactive because of a finding of incompetence, nine were inactive for other reasons — such as being deceased — and two were active, including the one who voted. That person was adjudicated in November 2018 and voted in April 2019, but has not voted since, McDonell said.

Possible out-of-state movers targeted

Other groups are also pushing clerks to purge voter rolls. In September, Wisconsin clerks received an email that claimed about 47,789 people had moved out of the state but, according to Bernegger, of the Wisconsin Center for Election Justice, were still active voters.

Bernegger asked clerks around the state to mark those who had left the state as “inactive” on the voter rolls.

In his email, which Wisconsin Watch obtained, he said he used WEC and the U.S. Postal Service’s change of address data to find voters who should be removed.

Wisconsin voters on the list for possible deactivation because they have moved can change their addresses at the polls on Election Day. Here, Alix Yarrow, left, registers to vote at the polling place at Olbrich Botanical Gardens in Madison on Feb. 18, 2020. Yarrow had recently changed addresses within the city. Assisting in the registration process are Kyle Richmond, center, and Aaron Schultz, right. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

Simply relying on something like the USPS database, which is optional and doesn’t include someone’s date of birth, to identify people who moved is problematic, said Becker, the ERIC board member and executive director of the Center for Election Information and Research.

ERIC works with states to identify voters who have moved out of a state and therefore are no longer eligible to vote there. But, he added, each state then relies on its own laws and policies before a voter is removed. In Wisconsin, local clerks contact voters directly to see if they’ve actually moved.

ERIC’s ‘sophisticated’ system

Wisconsin’s GOP-run Legislature mandated that the state join ERIC in 2015 to improve voter roll maintenance.

The software used by ERIC is “extremely sophisticated,” costs a lot of money and uses non-public data to compile the lists sent to states, Becker said.

Election officials and local clerks should strive to keep voter rolls as accurate as possible, Becker said, adding that every state inevitably has voter lists that include people who are no longer eligible and exclude eligible voters.

Both are a problem, he said, but the reality is that “well run” and “largely accurate” voter rolls pose little danger as very few ineligible voters are knowingly or unknowingly voting illegally.

“That number is not zero, but it’s really close to zero,” Becker said. “It’s remarkable how close it is to zero.”

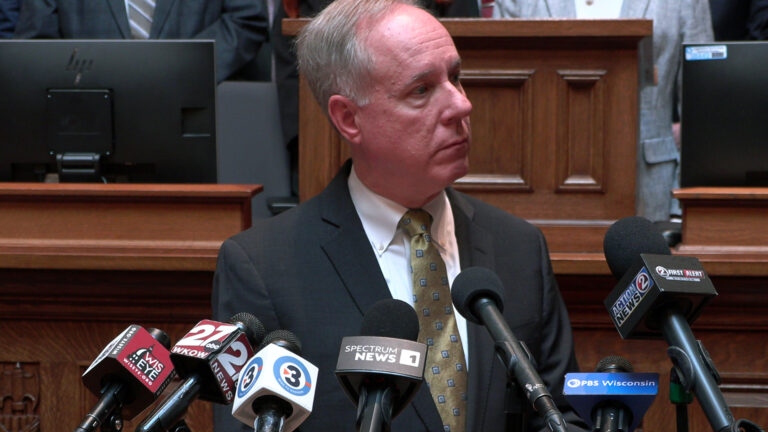

David Becker, executive director and founder of the Center for Election Innovation & Research, briefs the media on growing threats to election professionals at the Wisconsin State Capitol on Dec. 13, 2021. He says efforts by private groups to purge voters are often based on bad or misinterpreted data. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

Keeping the voter rolls accurate is an “essential function for all election officials,” WEC’s Vetterkind said. He added that the work of third-party groups is welcomed as they can sometimes help find “errors and inaccuracies.”

However, Vetterkind said these groups are not screened, can be partisan or can make incorrect statements about the law or rely on incomplete information. Responding to these groups is up to local clerks, Vetterkind said.

Bernegger acknowledged in his September email to clerks that not all 47,000 people he found had definitely moved and were no longer eligible voters. Bernegger and his attorney did not return messages seeking comment.

Activist has history of complaints

Bernegger previously filed complaints with the WEC about voters having improper addresses on their voter registrations. WEC dismissed the complaints, fined Bernegger $2,400 and called the complaints “frivolous.” Bernegger has yet to pay that fine, according to the WEC.

Fond du Lac County District Attorney Eric Toney, the Republican nominee for state attorney general, seized on Bernegger’s information and charged five people with felonies for registering to vote using a local UPS Store address.

One of those people previously told Wisconsin Watch that she didn’t know it was illegal to use that address, where she gets all her mail, as her voting address.

ERIC has become a target of activists, who claim it is a liberal voter fraud plot. Criticisms of the organization are similar to those against ballot drop boxes, absentee ballots and machines that count votes, Becker said, calling them “guardrails of democracy” that have contributed to more accurate and secure elections.

“And when the guardrails of democracy are attacked … that creates a period of uncertainty in which the losing candidate can incite anger and violence,” he said. “And that may be the intended result here. It may be that they’re just trying to set the stage for future anti-democratic behavior to deny any election that they lost.”

Incompetent voter case fuels suspicion

One of the factors driving the activists is that they have found at least one case of an improper vote being cast in 2020 — although a closer look at the circumstances in that case points to administrative error, not a sinister scheme to steal the election.

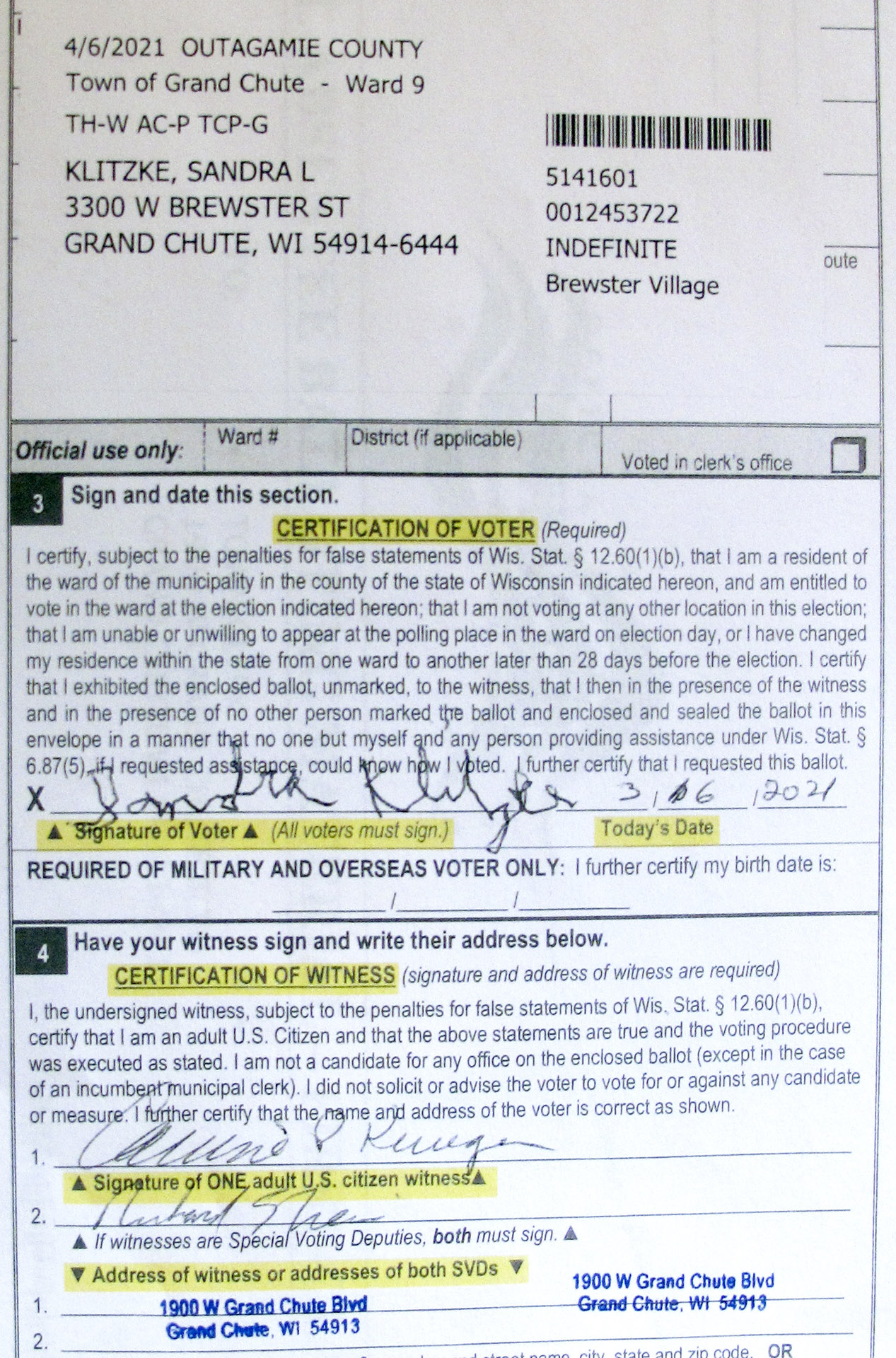

The case involves Sandra Klitzke, a resident of the Brewster Village nursing home in Outagamie County, who had voted in the November 2020 and April 2021 elections, even though a court had removed her right to vote in February 2020.

Thomas More Society lawyer Erick Kaardal interviews nursing home resident Sandra Klitzke in a video that was played at a Wisconsin Assembly elections committee hearing on March 1, 2022. Klitzke voted in 2020 and 2021 despite a court finding her ineligible, most likely due to administrative error. (Credit: Wisconsin Assembly Office of Special Counsel)

On March 31, the Thomas More Society filed a WEC complaint on behalf of Klitzke and her daughter, Lisa Goodwin, who stated she “could not explain why the WisVote voting records would have indicated that my mother voted” in the 2020 or 2021 elections. A third-party law firm investigated and dismissed the complaint on technical grounds in May.

Normally the county register in probate mails notification of an ineligible voter to the WEC, according to Jennifer Moeller, president of the Wisconsin Register in Probate Association. The WEC then updates its information and notifies the local clerk, who is the only official authorized in Wisconsin to deactivate a voter’s registration.

It’s unclear why Klitzke’s name was not switched to “ineligible” in the WEC voter file. Both the WEC and Outagamie County officials said court records related to Klitzke’s guardianship information are confidential under state law.

System breakdown?

Town of Grand Chute Clerk Kayla Filen, who was not clerk at the time, confirmed her office did not deactivate Klitzke’s registration until April 2022.

Klitzke had been registered as an indefinitely confined voter dating back to 2007 and had voted as recently as 2017 before the 2020 election, Filen said. She was also listed as indefinitely confined in 2020. Indefinitely confined voters automatically receive absentee ballots without having to request them, Filen said.

A Wisconsin Watch review of Klitzke’s absentee ballot envelopes from 2020 and 2021 show them both signed in a shaky hand. In the 2020 election — when the WEC suspended the state’s special voting deputy program in nursing homes because of the pandemic — an employee at the county-owned facility had signed as a witness.

This absentee ballot envelope shows that Sandra Klitzke voted in 2021 even though an Outagamie County judge had found her incompetent to vote in 2020. (Credit: Jacob Resneck / Wisconsin Watch)

In 2021, two witnesses from the town of Grand Chute signed the envelope, reflecting the normal process of special voting deputies witnessing nursing home voting.

Outagamie County Executive Tom Nelson, a Democrat, said the case feels “manufactured.”

“They probably had to search high and low to find one case, we all know that there’s a lot of money, there’s a lot of horsepower behind this and for whatever reason, they’re targeting Outagamie County,” Nelson said in an interview. “And I stand by the county clerk, and I stand by the Brewster Village administrator completely and fully.”

Activist undeterred

Heuer said there are more cases out there as “many” people have come forward with stories of loved ones with cognitive disabilities voting.

His group has filed public records lawsuits in Brown, Crawford, Juneau, Kenosha, Lafayette, Langlade, Marquette, Ozaukee, Polk, Taylor, Vernon, Vilas and Walworth counties to obtain the names and addresses of everyone under guardianship. A Juneau County judge ruled against the Wisconsin Voter Alliance on Aug. 24 but the other cases are pending.

Disability Rights Wisconsin opposes the release of the names and lobbied WEC to shield the names of incompetent ineligible voters in the public voting file, said Barbara Beckert, Disability Rights Wisconsin’s external advocacy director.

“A lot of the communication related to this issue over the past year or so while all these different investigations have been going on has been confusing and at best misleading and sometimes very clearly inaccurate,” Beckert said. “Our experience has been that often people under guardianship aren’t certain whether or not they have the right to vote.”

The group has successfully helped restore some people’s voting rights, for example, someone who was deemed incompetent to vote at age 18 because of a developmental or cognitive disability, but is older now and no longer under the guardianship of a parent.

During the pandemic, Beckert said her organization reminded nursing homes across the state that Medicare and Medicaid guidelines require them “to affirmatively support the right of residents to vote.”

“Why aren’t we concerned about the vast majority of people who live in these facilities who have the right to vote and who might not be able to exercise it?” Beckert asked.

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us