How Milwaukee's top election official worked to restore trust after missteps

The Milwaukee Election Commission has instituted a 26-point checklist to ensure the integrity of ballot counting and reassure the public following criticism of its handling of the 2020 election, when real and perceived missteps fed into false allegations.

Wisconsin Watch

April 9, 2024 • Southeast Region

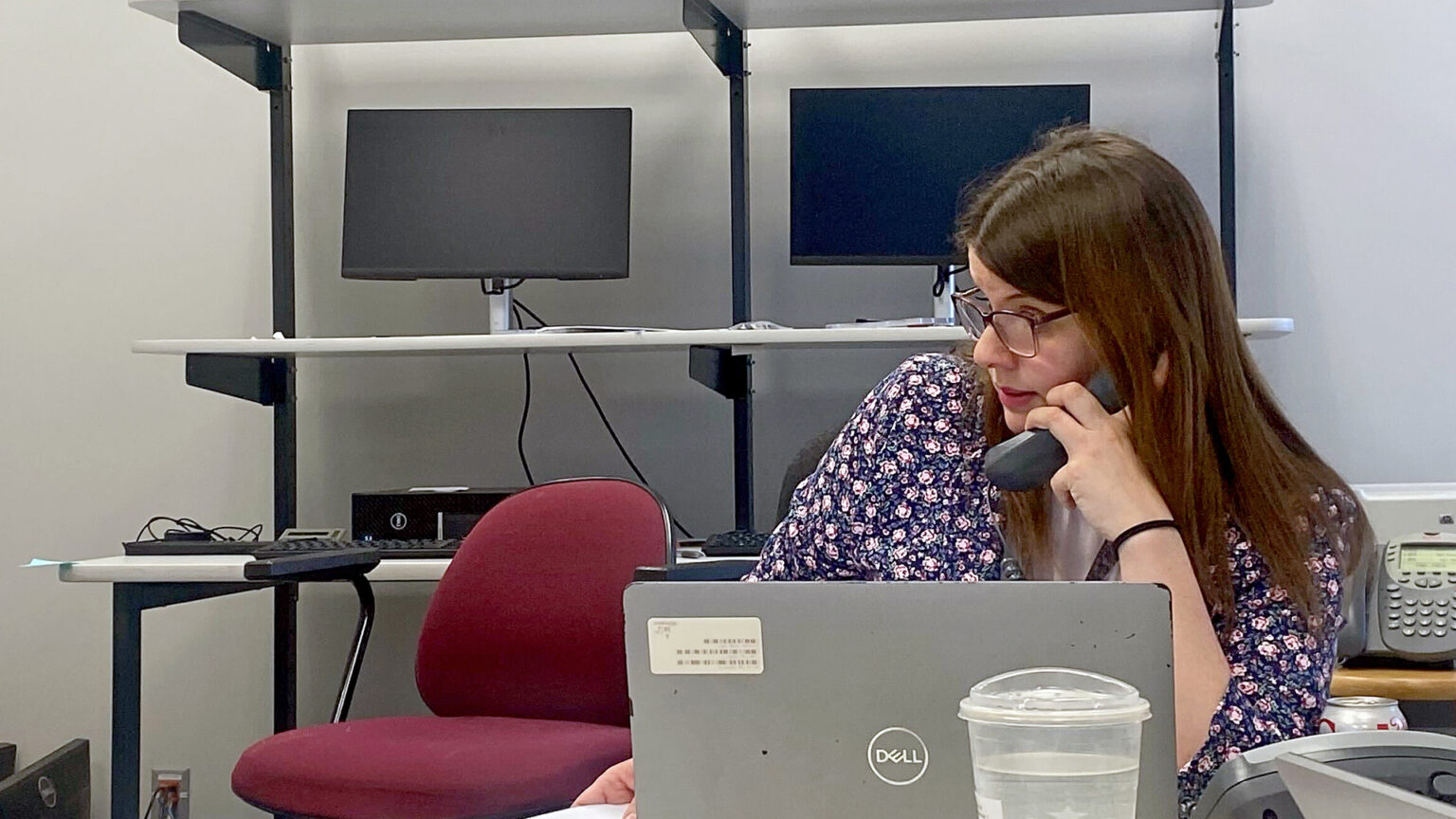

Claire Woodall, Milwaukee's chief election official, works from the Milwaukee Election Commission office on April 2, 2024, at City Hall in Milwaukee. Woodall has implemented a 26-point checklist to ensure missteps from the 2020 election aren't repeated. (Credit: Alexander Shur / Votebeat)

This article was first published by Votebeat and Wisconsin Watch.

Before a single vote is counted at Milwaukee’s central counting facility, Step 1 is for an election official to check every ballot tabulator to make sure the number of absentee ballots processed so far is zero. Hours later, and after several thousand ballots have been scanned, comes the climax: a late-night delivery of the voting results at the county’s election office.

In between is a meticulous process to make sure thumb drives carrying vote totals in Wisconsin’s largest absentee ballot processing facility end up where they’re supposed to, aren’t tampered with and remain tracked through a full chain-of-custody process.

All 26 steps are covered by a checklist that Milwaukee Election Commission Executive Director Claire Woodall developed after the same process went awry four years earlier, landing her in the crosshairs of some who falsely accused her of rigging the 2020 election.

Woodall devised the checklist in consultation with a Republican who was wary of the city’s lack of an official policy for extracting absentee ballot election results and sending them to the county. It was one of a handful of changes Woodall has implemented recently in reaction to criticism of her office’s handling of the 2020 election, when real and perceived missteps fed into false allegations.

The new policies, Woodall said April 2, are about balancing two priorities: “We’re appeasing those folks,” she said of the critics and skeptics. “But we’re also protecting ourselves by giving as much transparency as humanly possible.”

Woodall spoke to Votebeat during the April 2 primary election from her City Hall office, where she and other Milwaukee Election Commission staff spent most of the day troubleshooting minor issues, from political activists electioneering too close to a polling site to voting machines briefly jamming. Meanwhile, city residents cast just over 85,500 votes, including over 26,000 absentee ballots, at 181 polling sites.

The 2020 presidential contest was Woodall’s first general election as Milwaukee’s top election official, and it still hovers over her work.

That year, after officials finished tabulating absentee ballots at the city’s central counting facility in the wee hours after Election Day, Woodall left with a police escort to deliver the flash drives containing the vote totals to the Milwaukee County elections office. But she forgot one of the 12 flash drives at central count, a mistake some conservatives seized on as a flagrant oversight.

Some went further and alleged that Woodall and other election officials tampered with the results, noting that the 3 a.m. slip-up happened right around the time Milwaukee officials updated the results with votes from 169,000 absentee ballots, which broke heavily for Joe Biden.

There’s no evidence of any such tampering, and a recount confirmed the initial election results, but Woodall said her error prompted a Republican election worker, Sheila Stapleton, to suggest creating a new chain-of-custody policy to increase trust with the public.

The suggestion came just before the November 2022 midterm election, around the time the Milwaukee election office was caught in the middle of another scandal, Woodall said.

As city officials prepared to administer the election that year, then-Milwaukee Election Commission Deputy Director Kimberly Zapata told Woodall that she had requested three military absentee ballots under fake names to be sent to the home of a Republican state Assembly member. Zapata was quickly fired, but the news sullied the office’s reputation and shook up Milwaukee’s election operation.

On short notice, Woodall had to take over for Zapata to manage the central count for that election and, in the aftermath of the firing, noticed an air of skepticism among the workers she was supposed to train.

“That weekend, I was just in a mode of like, wow, we have abandoned all trust now after this has been the news story this week.” she said. “And so really just trying to be extra patient and listen to all of their concerns.”

Woodall develops new election policies to restore trust

Stapleton’s concern, the issue she raised with Woodall in 2022, was that there weren’t official policies to make sure the USB drives inserted into tabulators had zero counted ballots before they started recording vote counts, or to ensure the secure transfer of city absentee voting results to the county level.

Without those policies, Stapleton said, “How do we even know what’s going on once the data is taken off the machines?”

Woodall and Stapleton then developed a version of what has now become a 26-point checklist. The goal was to show that the USB drives carrying the city’s absentee ballot election results were visible to the public and untampered with as they moved from the city to the county, she said.

With the new checklist, Stapleton said, “I’m a lot more confident in the process of just knowing that the flash drives have been properly formatted, properly downloaded and properly maintained.”

Per the checklist, after a member of the Milwaukee Board of Absentee Canvassers ensures tabulators show no processed ballots at the start of the day, the election official leading the central count operation — in public view — clears and reformats the flash drives that’ll store the election results from each machine.

Later in the process, after completed absentee ballots are fed into the tabulator, the official goes from machine to machine, inserting the USB sticks in the tabulators to export the results. After every machine’s results are exported, the official places the flash drive in a clear, tamper-proof bag in public view.

On April 2, several election observers along with a Republican and Democratic city election commissioner observed Milwaukee Election Commission Deputy Director Paulina Gutiérrez to deliver the USB drives to the county.

Milwaukee Election Commission Deputy Director Paulina Gutiérrez prepares to export absentee ballot election results from a tabulator on April 2, 2024. (Credit: Alexander Shur / Votebeat)

The city-to-county handoff is a feature of Wisconsin’s decentralized elections, with about 1,850 clerks administering elections at the municipal level and then each providing the results to the state’s 72 county clerks, who are required to post unofficial results to their websites.

The new Milwaukee procedures “support the integrity of the process, to show voters that it is the proper chain of custody so that there’s no perception of inaccuracies occurring,” said Douglas Haag, the Republican commissioner who observed the handoff between the city and county on April 2.

Before the new process, election observer Jefferson Davis said he had “major concerns” about the chain of custody in Milwaukee. Davis, a former Menomonee Falls village president, is a conservative election activist who has entertained and promoted conspiracy theories.

Since then, Davis said, Milwaukee election officials have “done more than they need to, to assure us that this is being done right.”

Davis spent hours at the central count facility on April 2, sitting in front of election workers processing absentee ballots and walking around to watch workers tabulate votes. He checked where the tabulators and their access points were, figured out the floor plan of central count, observed how many election workers were at each table, and watched to ensure the correct ballots were going to the right workers.

“We’re not suggesting anything. We just want to be part of that process, which they’re always very good about,” he said. “You can’t find better people than Claire, Paulina.”

But others remained skeptical.

Just before 8 p.m., as absentee ballot counting was wrapping up, election officials at central count were notified that they just received the Postal Service’s final delivery of the night: 150 absentee ballots. Workers were notified there would be a slight delay in finishing up work.

After officials tabulated those ballots, Gutiérrez and the partisan election commissioners watching her work left central count at about 9:45 p.m. and arrived at the county courthouse about 15 minutes later to deliver the city’s unofficial absentee ballot results.

The results, posted soon after, were enough to swing the previously reported margin on a city referendum the other way, leading to the passage of a measure to spend $252 million on Milwaukee Public Schools.

Shortly after, conservative radio host Dan O’Donnell posted on social media, in an apparently sarcastic reference to the city’s overnight 2020 upload of absentee ballots, “No way: Late night votes in Milwaukee have won an election for liberals. That sort of thing NEVER happens here!”

“I don’t know why anyone thinks voting is real anymore,” another social media user responded.

Election officials and experts have repeatedly explained that updating election results with absentee ballot totals can often cause shifts like this because of the difference in voting patterns between Republicans and Democrats. But even with the new processes and close public scrutiny, their message is often contradicted by people who raise baseless suspicion.

Addressing more election concerns, but still facing hurdles

Other measures grew from Woodall’s effort to address various election concerns since 2020.

In late 2021, Peter Bernegger, an election conspiracy theorist who has been convicted of fraud, filed a public records lawsuit against her alleging that she was part of a “sect” of Milwaukee election officials who, with the help of an unnamed man from Illinois, printed pre-filled ballots for Biden in a “hidden room.”

That room he was referencing was a conference room in the Milwaukee Election Commission’s City Hall office filled with printers, telephones, monitors, and some extra unused absentee ballots.

Although Bernegger’s claims were baseless, Woodall added a keycard lock to the room this year so the commission could track who had access to it. The room previously had key access, and only authorized staff got keys, but it was harder to tell who entered the room, Woodall said.

With the new lock, she said, “We are able to say, look, here’s the audit record of everyone who entered that room: What is the accusation?”

Using a private grant, Woodall also purchased about 20 more cameras to monitor the central count facility.

The purchase wasn’t a direct response to any specific accusations, Woodall said, but rather a proactive measure that will allow city officials to provide video records in case something goes awry — or if somebody makes false allegations that officials want to refute.

Despite Woodall’s efforts, the election office continues to face scrutiny, sometimes for its own mistakes.

Just after Zapata, the former Milwaukee deputy election official, was convicted for absentee ballot fraud and misconduct in office in March, reports emerged that almost 220 Milwaukee residents received absentee ballots for the incorrect ward.

“Horrible week for that to happen,” Woodall said.

The Election Commission alerted the residents, issued them new ballots, and developed plans to make sure only one of the ballots they were issued would be counted, Woodall said.

Woodall said there are still bound to be some mistakes because of human error and technological faults, but she said the goal is to make sure voting is 100% accurate.

“I think all we can do is continue to be totally transparent, both in our successes and our failures … regarding all aspects of election administration.” she said. “I mean, we didn’t hide the wrong ballots. We didn’t try to conceal it. We immediately went public, wanting to alert voters, to double check our work.”

Alexander Shur is a reporter for Votebeat based in Wisconsin. Contact Alexander at [email protected]. This article is made possible through Votebeat, a nonpartisan news organization reporting on voting access and local election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat’s free newsletters here.

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us