Hagedorn says time ran out for Wisconsin's redistricting process

After the U.S. Supreme Court sent the matter back to the state level, the Wisconsin Supreme Court's conservative majority approved in a 4-3 decision legislative redistricting maps it had previously rejected in another 4-3 decision – the swing vote was Justice Brian Hagedorn, who opined the window to consider Voting Rights Act claims had closed.

By Zac Schultz

April 18, 2022

(Credit: Legislative Technology Services Bureau)

“The timing does not work.”

With that phrase, Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Brian Hagedorn summarized why he reversed his prior decision and voted to put the Republican-controlled Legislature’s “least change” legislative redistricting maps in place, essentially locking in that party’s control of the Assembly and state Senate for the next decade.

The timeline to redraw Wisconsin’s legislative boundaries was not a surprise. The redistricting deadlines were known a decade ago, and yet Hagedorn wrote the Court essentially ran out of time to properly fulfill requirements placed on it by the U.S. Supreme Court.

On March 3, Hagedorn joined the three liberals on the state Supreme Court to select legislative and congressional maps proposed by Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat. Republicans appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, saying the maps violated the Voting Rights Act by using the race of voters “without sufficient justification” to determine Assembly boundaries around Milwaukee.

On March 23, in an unsigned decision, the U.S. Supreme Court wrote the Evers maps erred in saying the Voting Rights Act required them to create a seventh Black-majority Assembly district in the area. The Court wrote before invoking the Voting Rights Act, the districts had to meet certain preconditions. While sending the maps back, the Court gave Wisconsin’s Supreme Court options: “On remand, the court is free to take additional evidence if it prefers to reconsider the Governor’s maps rather than choose from among the other submissions.”

The U.S. Supreme Court did not find any violations with Evers’ congressional map. Those remain in place.

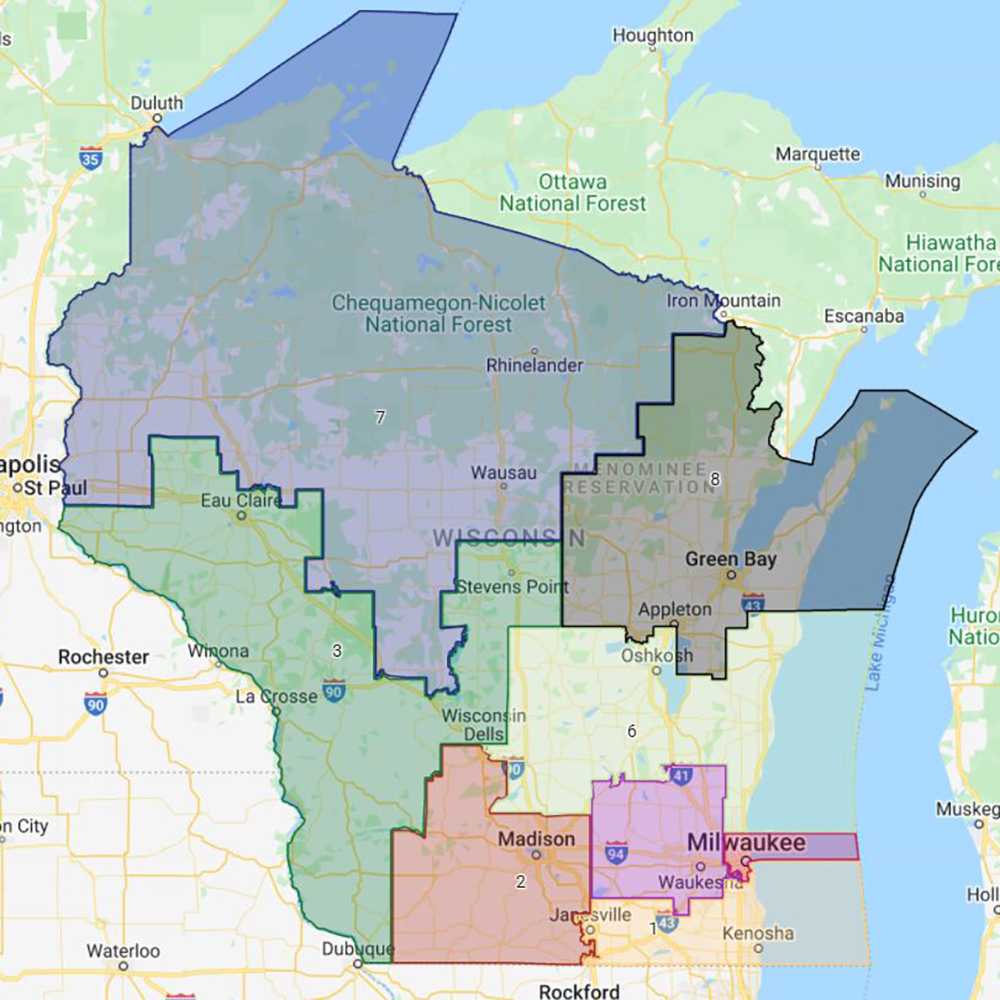

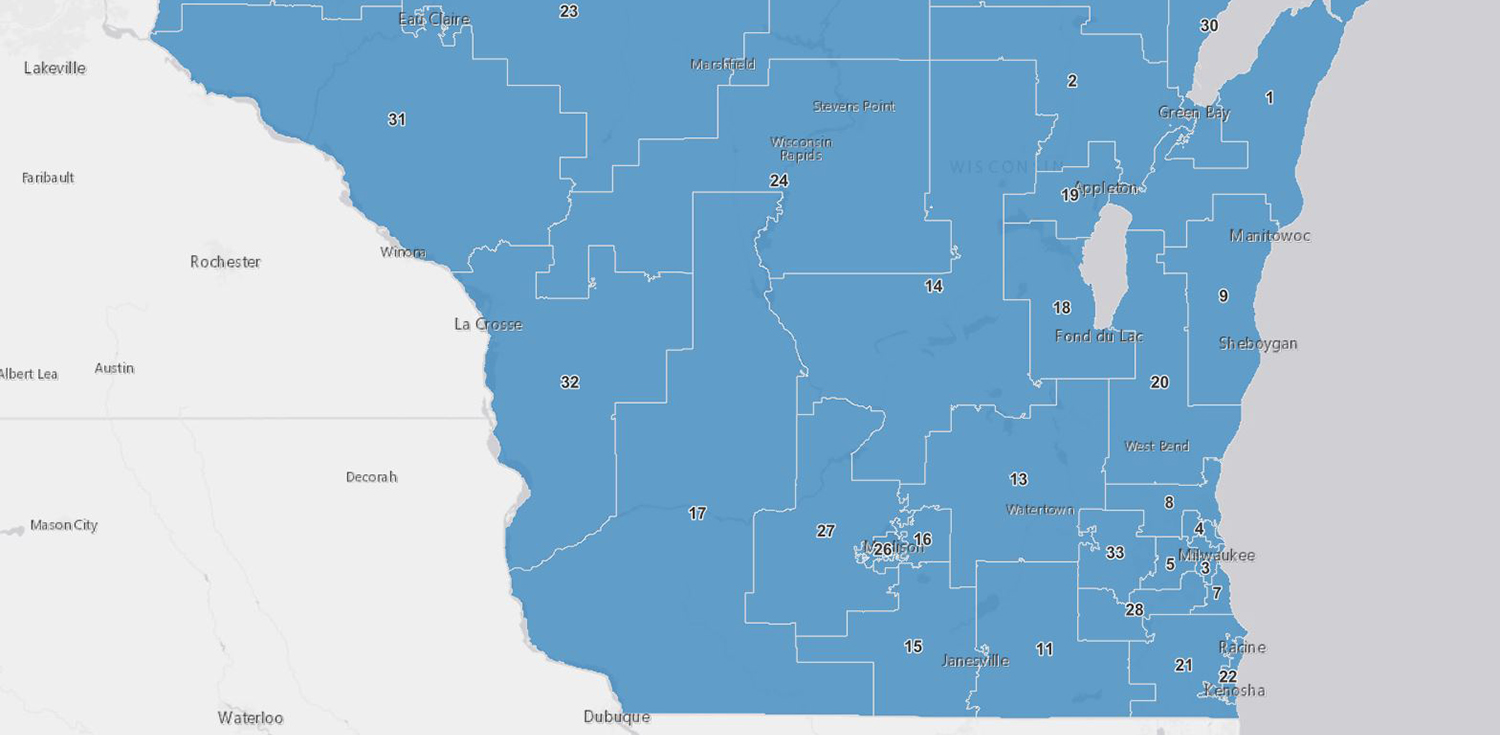

A map shows the “least change” redistricting of congressional seats submitted to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, which approved it in a 4-3 decision. The U.S. Supreme Court denied a request to reject these districts, which means the map will be in place for the 2022 midterm elections. (Credit: Office of Gov. Tony Evers / Google)

In the three weeks following that decision, many Democrats around Wisconsin speculated the state Supreme Court was revising Evers’ maps to put them in compliance with the U.S. Supreme Court. Instead, the state justices were trading barbs in a 147-page decision issued late in the afternoon on Friday, April 15 that included concurrences referencing Star Wars and Eminem and a dissent filled with nautical references and allusions to the Homeric epic the Odyssey.

Hagedorn ended up siding with the three other conservatives on the court and approved the Republican-drawn legislative maps that were introduced by the Speaker and Majority Leader, and passed by the Legislature, declaring they were race-neutral.

“None of the parties have established that the Legislature’s race-neutral maps violate the VRA. At most, the parties in opposition to those maps raise arguments without evidence,” read the majority’s opinion, written by Chief Justice Annette Ziegler, who was joined by Hagedorn along with Justice Rebecca Bradley and Justice Patience Roggensack.

In a concurring opinion, Hagedorn acknowledged the Wisconsin Supreme Court did not know what they were doing: “[a] majority of this court did not understand itself to be adjudicating a VRA claim … Had we understood our task this way, this court likely would have taken a different approach to this litigation.”

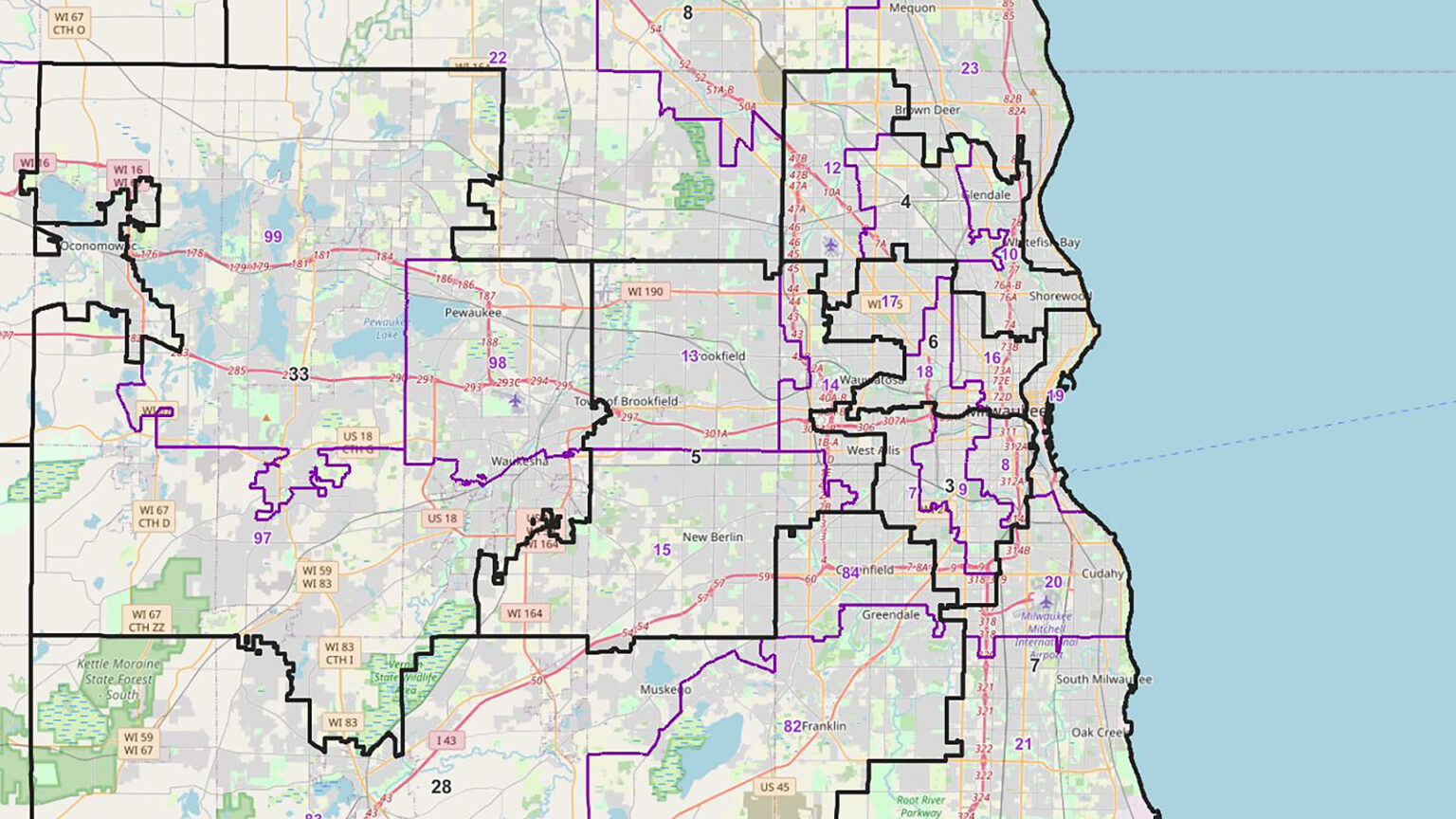

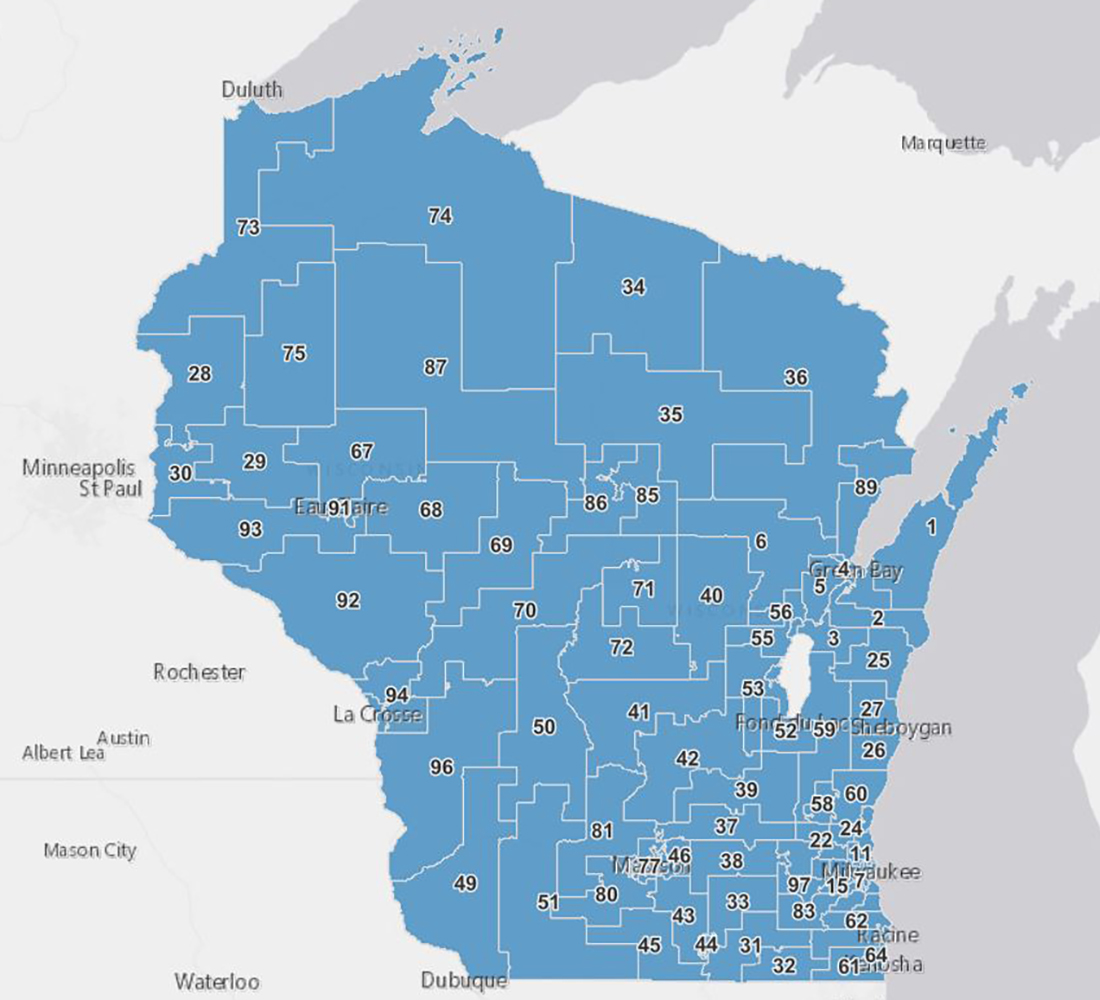

A map shows the “least change” redistricting of Wisconsin Assembly seats submitted to the Wisconsin Supreme Court by the Republican legislative majority. Citing the Voting Rights Act, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the “least change” maps submitted by Gov. Tony Evers , which had been previously approved by Wisconsin’s high court in a 4-3 decision. The state Supreme Court subsequently approved the Republican legislative maps as conforming with the Voting Rights Act in another 4-3 decision. Justice Brian Hagedorn was the swing vote in each instance. (Credit: Legislative Technology Services Bureau)

The Wisconsin Supreme Court has never been directly involved in the redistricting process. In past decades, if the Legislature and governor could not agree on maps the issue was decided in federal court.

The intense focus on this round of redistricting began in 2011, after then Gov. Scott Walker and his fellow Republicans in the Legislature used non-disclosure agreements and a private law firm to create a gerrymandered map that entrenched the latter in power for the next decade.

Counties around the state passed non-binding referenda demanding a non-partisan redistricting process, and Democrats campaigned in the 2020 election on preserving Evers’ veto authority as governor so Republicans couldn’t pass another set of gerrymandered maps.

As the 2021-22 legislative session started, both parties moved to have the issue decided in their preferred venue. Democrats filed suit to have the issue settled in federal court. Republicans filed suit to have the Wisconsin Supreme Court hear the case. Political observers correctly assumed the Republican-controlled Legislature and Evers would not be able to reach a compromise.

Starting in September 2021, the Wisconsin Supreme Court started hearing arguments about how to draw or choose a map. Hagedorn was the deciding vote at each step of the process. When he wrote the decision choosing the Evers maps submitted to fit a “least change” standard sought by the Court, the Justice assumed any challenges based on the Voting Rights Act would be taken up in an appeal.

“Our process of choosing from among a discrete group of proposals — a method recommended by several parties — was a poor vehicle for conducting the kind of VRA analysis the Supreme Court indicates we should have done … we anticipated further litigation involving a fully developed Equal Protection or VRA claim could, and likely would, follow,” wrote Hagedorn in his concurrence.

Despite Hagedorn initially saying he expected a Voting Rights Act analysis to happen after he chose the Evers maps, he subsequently said there’s not time.

“Most notably, our record is, at best, incomplete. One solution could be to develop a fuller record, make factual findings, and adjudicate a VRA claim with a firmer factual foundation. But the timing does not work,” Hagedorn wrote.

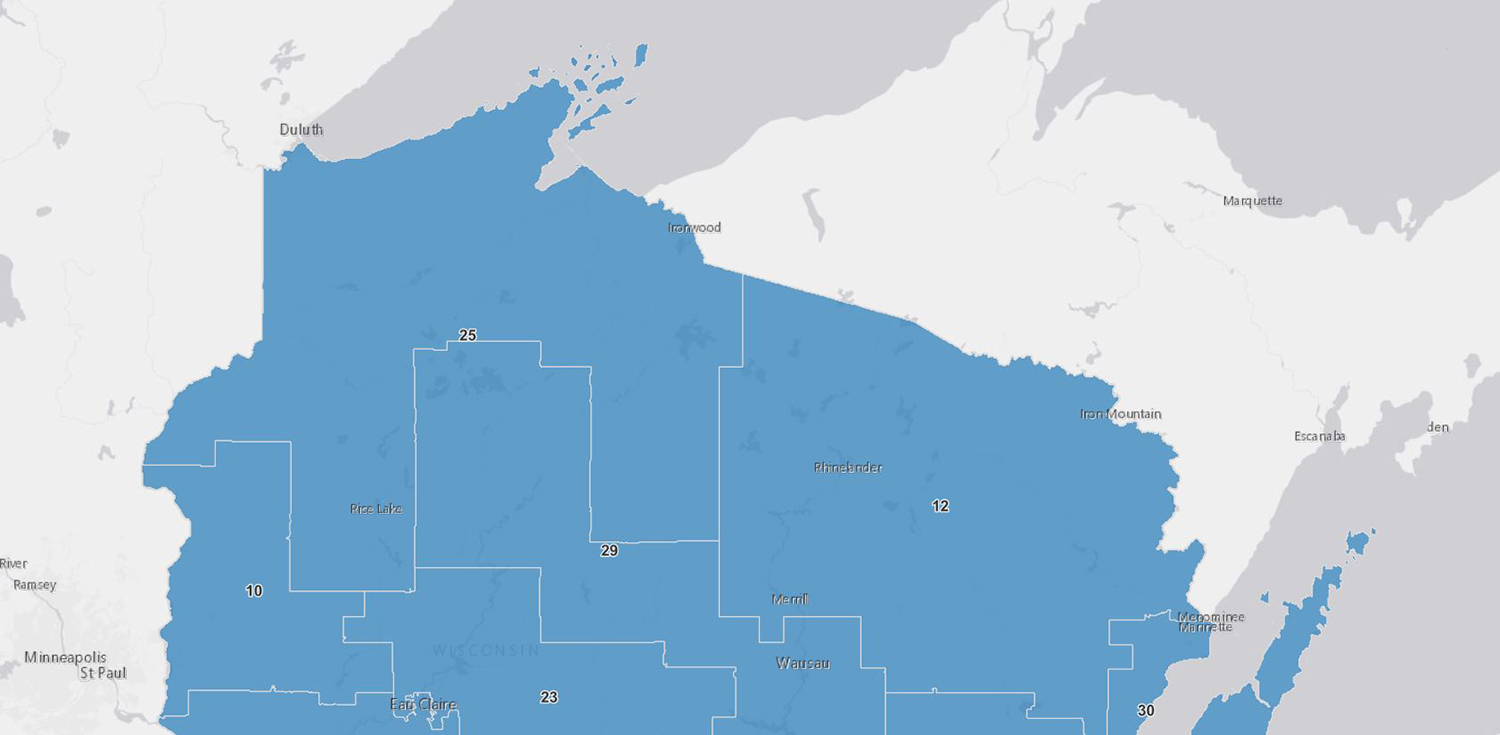

- A map shows the “least change” redistricting of Wisconsin Senate seats in the northern half of the state submitted to the Wisconsin Supreme Court by the Republican legislative majority. (Credit: Legislative Technology Services Bureau)

- A map shows the “least change” redistricting of Wisconsin Senate seats in the southern half of the state submitted to the Wisconsin Supreme Court by the Republican legislative majority. (Credit: Legislative Technology Services Bureau)

April 15 marked the date on which candidates for the fall 2022 election could start circulating nomination papers. Local clerks needed to know the boundaries of the districts because candidates can only gather signatures from voters in their districts. Signatures are due on June 1, and the primary election is on August 9.

“The window of opportunity to conduct a fresh trial with new evidence, new briefing, and potentially new arguments is well past,” wrote Hagedorn.

In the primary opinion, Ziegler wrote it was Evers’ fault for not anticipating a decision from the U.S. Supreme Court that even the Wisconsin Supreme Court didn’t anticipate.

“The Governor stipulated that no discovery outside briefs and expert reports produced for the court was needed. Not once did the Governor notify the court that there was a need to develop a more detailed record or that the procedures adopted by the court failed to permit adequate discovery. The Governor chose to place his case on the evidentiary support included in his briefs and expert reports, and as the Supreme Court held, that evidence was not sufficient to justify racially motivated district lines,” wrote Ziegler.

In her dissent, Justice Jill Karofsky repeatedly referenced Homer’s Odyssey.

“This case has been nothing short of an odyssey——a long wandering marked by many changes in fortune.”

In the ancient epic poem, the protagonist was trying to return home from war, but in this case, Karofsky suggested the first mistake was the Court going on the trip at all.

“Our initial miscalculation was embarking on this journey in the first place,” she wrote.

Karofsky wrote that a federal court could have resolved the Voting Rights Act questions at trial.

“This court, in its hubris and desire to short-circuit a complicated process, thought it knew better. By both adopting a process that aimed to adopt a party submitted map despite glaring partisan motivations and limiting the arguments to appellate-style briefs, written expert reports, and oral presentation to this court, we received too thin a record on which to make determinations with absolute certainty,” wrote Karofsky.

While there will likely be more lawsuits related to the Republican “least change” maps — likely based on the Voting Right Act and the appropriate number of Black-majority Assembly seats around Milwaukee — the rest of the map will “likely” keep lines that favor Republican candidates.

The next round of redistricting will start in 2031 and need to be complete by April 2032.

Karofsky urged next time, the Wisconsin Supreme Court should step aside.

“The redistricting process is likely to stalemate and come before this court again in the future,” she wrote. “And when it does, I hope that we have learned our lesson. I hope that we will permit a politically insulated federal court to manage the task. Federal courts are better able to conduct extensive fact finding through trial-style litigation, a task for which we proved ill equipped.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us