Gray Wolf Population In Wisconsin Maintained Even During Hunting Seasons

In an attempt to educate and advocate for state control of the gray wolf population, Wisconsin state legislators Sen. Tom Tiffany, R-Hazelhurst, and Rep. Adam Jarchow, R-Balsam Lake, hosted the Great Lakes Wolf Summit in September 2016.

March 6, 2017

Aerial photo of four gray wolves in winter

In an attempt to educate and advocate for state control of the gray wolf population, Wisconsin state legislators Sen. Tom Tiffany, R-Hazelhurst, and Rep. Adam Jarchow, R-Balsam Lake, hosted the Great Lakes Wolf Summit in September 2016.

The summit, which took place in northern Wisconsin, brought together wildlife experts and representatives from other Great Lakes states, including Minnesota and Michigan.

At the summit, Tiffany stressed the importance of state control of the wolf population. He noted that in the years that wolves were taken off of the federally endangered species list, the state maintained control over the population and, even with hunting seasons, the wolf population maintained steady numbers.

“We had about three seasons where we hunted wolves successfully, and those numbers never dropped below 350,” Tiffany said. “There was no mismanagement by the state, and so I think that people can have confidence because we’ve already done it.”

But did the state really follow the guidelines put in place after the species was relisted? The numbers behind the statement tell a compelling story.

According to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Wisconsin is one of about a dozen states in the nation with a gray wolf population. A wolf pack’s territory can span 20-120 square miles, roughly one tenth the size of the average Wisconsin county, according to the DNR.

The Wisconsin DNR began monitoring the state’s gray wolf population in 1979, according to Adrian Wydeven, coordinator for the Timber Wolf Alliance at Northland College. Wydeven said the state also began to develop plans, policies and educational practices regarding wolves at that time.

By 1980, Wydeven said the gray wolf population in Wisconsin was 25, but by 1990, this number rose 34. According to Wydeven, this is when the Wisconsin wolf population really took off.

In 1999, the DNR drafted the Wisconsin Wolf Management Plan. This 193-page document outlines the long-term course of action for wolf management in the state. Most notably, this plan determined that once the wolf population across the state reached 250 (in areas outside of reservations), the gray wolf species would be delisted from “state threatened to a non-listed, non-game species.”

The gray wolf was federally delisted in 2012 after a 2011 winter survey estimated there to be between 782-824 wolves in the state. With this delisting came a state-led wolf management program and a renewed wolf hunting season.

DNR carnivore specialist Dave MacFarland explained that a state-led wolf management plan gives the Wisconsin DNR the ability to take lethal action against wolves. He said when the state first gained control of the wolf population, the population numbers were well within the parameters set in the 1999 plan.

But MacFarland said that even even though the state followed its management plan, there was controversy because not everyone agreed with the state’s objectives laid out in the Wisconsin Wolf Management Plan.

During the approved hunting and trapping seasons, MacFarland said the state stayed below the approved quota of wolves allowed to be hunted.

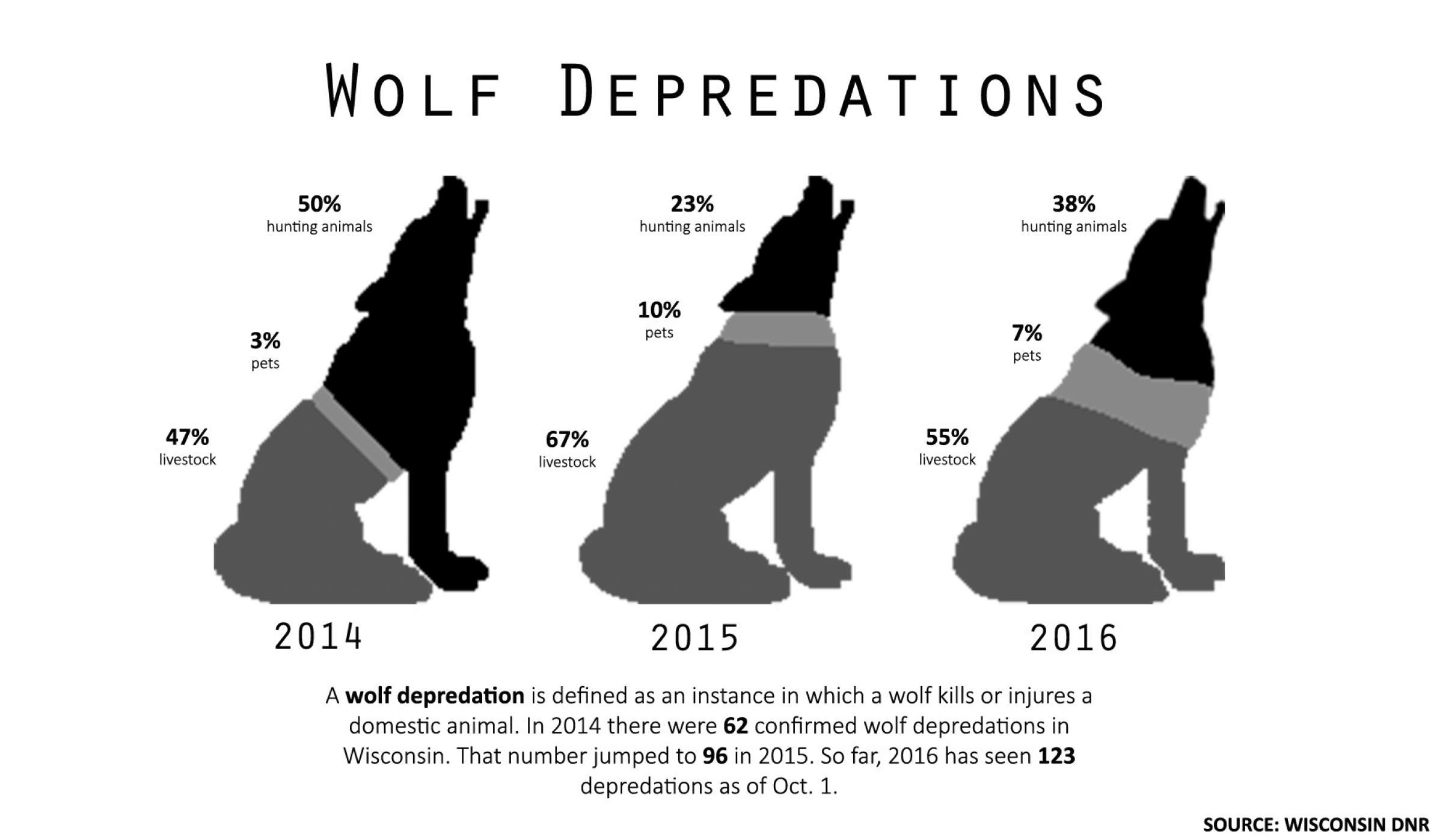

According to the DNR, 117 wolves were hunted during the 2012 wolf hunting season.

A December 2014 court order ruled the gray wolf as endangered; the species was officially put back onto the federal endangered species list in February 2015. But before being relisted, there were two more wolf hunting seasons in Wisconsin. The 2013 season saw a harvest of 257 wolves, a significant increase from 2012. The 2014 season brought in 154 wolves, about half as many as 2013.

According to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, U.S. District Judge Beryl Howell said federal regulations protecting endangered species trumps any policy reasons the Fish and Wildlife Service may have for wanting to delist the species.

MacFarland said during the three wolf hunting seasons between 2012-2014, the population never dropped below the approved 350 threshold. In spring 2012 the estimated wolf population was 815. In 2015 that number fell to 746. But in the most recent spring 2016 estimation, there are between 866-897 wolves in the state, MacFarland said.

“[The population] is higher now than it was prior to the delisting and it’s higher now than it’s ever been in the state,” MacFarland said.

MacFarland added, however, that since the relisting of the gray wolf, the DNR’s efforts to revise the management plan has been placed “on the backburner” of the organization’s priorities.

While the 1999 plan that originally defined this threshold hasn’t been officially updated since its implementation, MacFarland said that, while such plans are designed to last 10-20 years, the plan was re-evaluated and renewed in 2006.

While the hunting season did not endanger the gray wolf population, Wydeven, who ran the DNR’s wolf recovery program from 1990 to 2013, said the state could have done a better job fostering public engagement on the matter. According to Wydeven, the delisting of the gray wolf and the creation of a hunting season were pushed through the Legislature together when, in his opinion, they should have been two separate discussions.

Gov. Scott Walker approved Act 169 in April 2012, authorizing a wolf hunting and trapping season. In its 2012 wolf hunting season report, the DNR stated the goals of its first wolf hunt in 2012 were to reduce the Wisconsin wolf population with the ultimate goal of maintaining a sustainable population with fewer conflicts.

Wydeven said the Legislature overstepped its bounds by setting the rules for a wolf hunting season without letting the DNR decide several crucial details with public input. Wydeven said the DNR was unable to choose the dates and specific zones for wolf hunting season. He said, however, that hunting in Wisconsin can often become more of a “political” issue than a “biological” one.

Editor’s note: This report was originally published on Nov. 15, 2016 by The Observatory, a publication of the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. It fact-checked statements made by Sen. Tom Tiffany about wolves in Wisconsin.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us