Four Materials Illustrate Hazards Of Electronics Manufacturing

Operating an LCD screen manufacturing plant in Wisconsin would raise a number of environmental question marks.

August 14, 2017

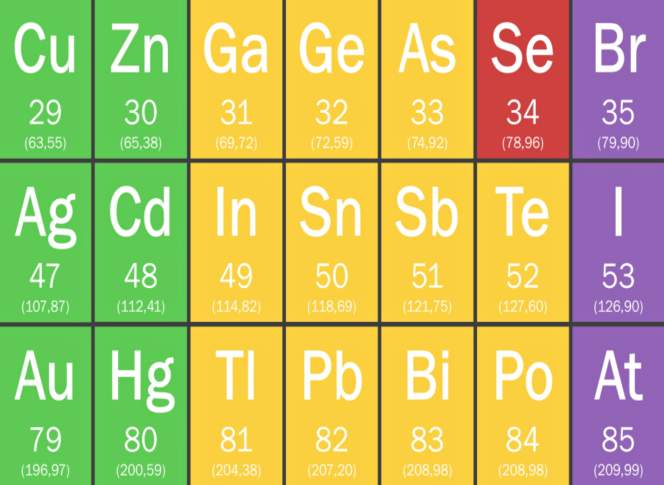

Periodic Table crop

Operating an LCD screen manufacturing plant in Wisconsin would raise a number of environmental question marks. Any sophisticated, modern electronic device, including the products Taiwanese company Foxconn proposes to make at a new factory in the state, will contain a complex array of metals, gasses and other chemicals.

“The usual phrase is, there’s about 60 elements of the periodic table that sit in front of us when we use our smartphone or laptop computer,” said Avtar Matharu, a professor of chemistry at the University of York in the United Kingdom. The specific mix of materials gradually changes as manufacturing processes and the devices themselves change, but there are environmental constants across the industry, like the heavy demands it places upon water resources.

“Manufacturing all kinds of electronics is extremely chemical intensive,” said Benoit Cushman-Roisin, a professor of engineering sciences at Dartmouth College. “Typically the manufacturing process involves using many more times in weight in chemicals than end up in the body of what’s being manufactured. You have to edge, you have to solder, there are fumes [and] you have to rinse many times.”

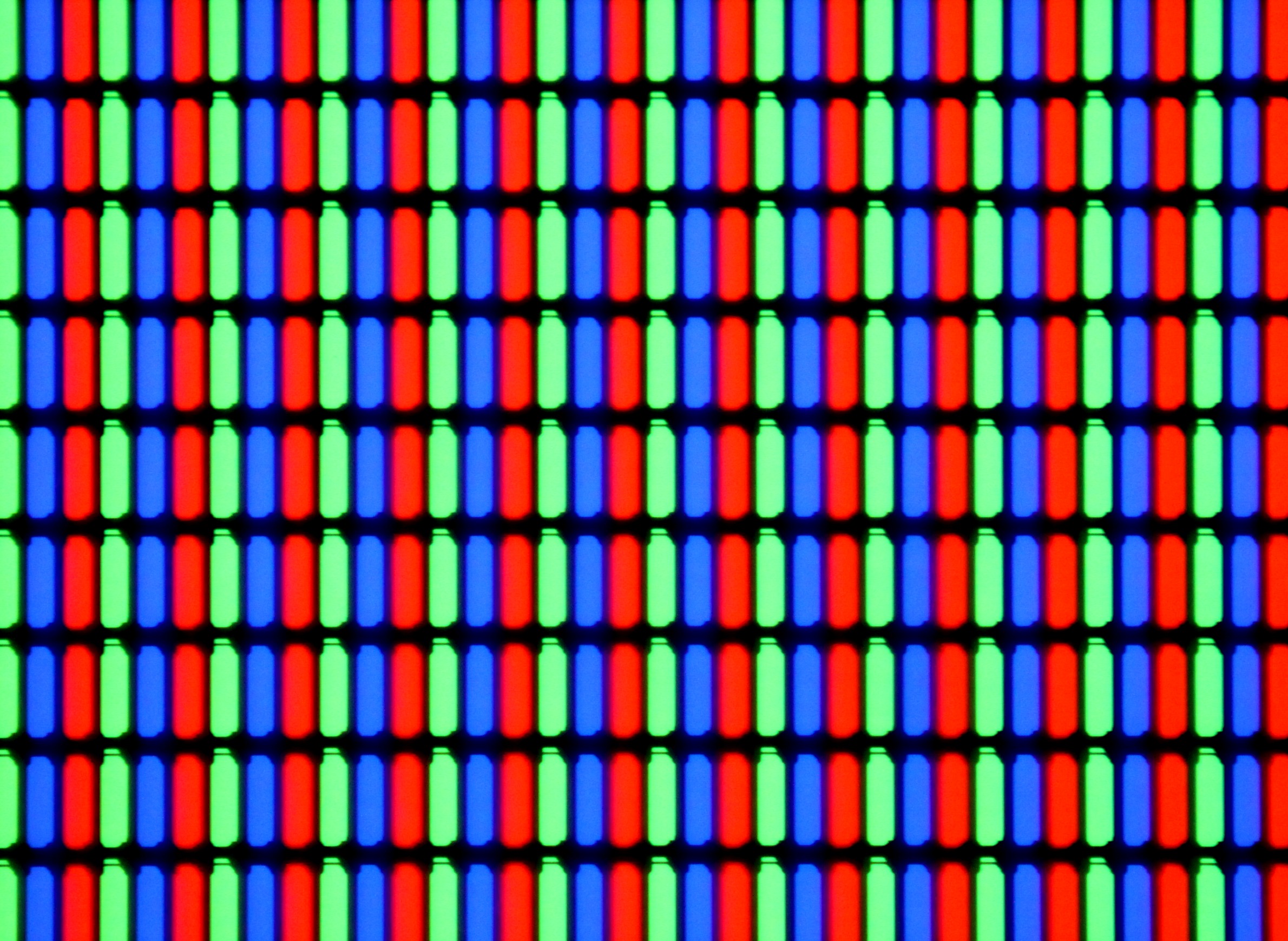

The core of a liquid-crystal display itself consists of several layers with liquid crystals — a type of matter with structural properties of both liquids and solid crystals — sandwiched in the middle of glass panes.

The environmental impact of a Foxconn manufacturing facility in Wisconsin will depend on large part on how much of the operation involves fabricating LCD components and how much of its work is simply assembling these parts into finished products like flat-screen TVs. Foxconn hasn’t revealed its plans in detail yet, but it would be a historic shift to have LCD fabrication in the U.S. on any large scale. These activities have largely been concentrated in Asia so far.

“It tends to be that the worst chemical and environmental impacts are at the base level where the basic components of electronics are being manufactured,” Cushman-Roisin said. “There’s usually a lot less environmental impact in final assembly and packaging, as a general rule.”

Beyond what substances a given factory releases into the air, water and soil, there are also the broader demands electronics manufacturing places on natural resources. For instance, electronics including LCD screens use a lot of rare-earth metals. These elements are not actually all that rare, but they’re typically not found in concentrated levels like many regularly mined metals. More importantly, they are in such demand that more people in the industry are beginning to think about how to use those resources more sustainably, in part by recycling these elements from discarded devices.

Matharu said it’s important for the public to understand how resource-intensive their electronics devices are. “Some of those resources are critical,” he said. “So in a way, protect the article that you have until the scientists develop very, very clever solutions to recover the resource.”

At its factories overseas, Foxconn has drawn scrutiny for a number of environmental concerns, including accusations that it dumped toxic heavy metals into rivers and sewers, and endangered workers with its use of industrial solvents.

For all the concerns Foxconn’s record raises, the electronics industry has also demonstrated that it can make environmental advances.

Well after lead was banned from being used in paint and new water pipes, the metal remained common in the soldering material electronics manufacturers used to assemble computers and other products. During the 1990s, the industry undertook a big effort to get rid of tin-lead solder. This happened in part due to government pressure, especially in the European Union, but largely because of a push from manufacturers themselves, said Richard Ciocci, a professor of mechanical engineering at Pennsylvania State University at Harrisburg.

LCD makers have also reduced one of their products’ major environmental drawbacks — mercury. The highly toxic element was initially a key component of backlight lamps for LCD screens. But the presence of mercury also makes the screens difficult and dangerous to recycle. Therefore, manufacturers have been increasingly ditching mercury-containing lamps in favor of LED light sources for the displays, said David Hsieh, a Taipei-based analyst who follows the displays world for financial intelligence firm IHS Markit.

Matharu points out that electronics manufacturers have a financial incentive to minimize the amount of chemicals they release into the environment.

“Manufacturing is all about efficiency, so you want to make sure that every bit of resource that comes in is used to its maximum,” he said.

Of course, that doesn’t prevent accidents or environmentally unsound practices. Hsieh credits LCD manufacturers in Asia for improving their environmental practices and says that accidents among the continent’s 100-plus manufacturing facilities are rare, but he cautions against legislative efforts to carve out environmental exemptions for Foxconn.

“LCD [fabrication] is a kind of new thing for a beautiful state like Wisconsin, so it should be more careful,” Hsieh wrote in an email.

Some observers interviewed about the electronics industry have a wary perspective — Cushman-Roisin called it “probably the dirtiest industry that we have in the world right now” — while others were cautiously optimistic about manufacturers’ ability to continue reducing their environmental impact.

Wisconsin has long been exposed to many forms of agricultural and industrial pollution, but large-scale electronics manufacturing might bring some new twists. It won’t be entirely clear what quantities of what substances a Foxconn LCD factory would use until the company rolls out more specific plans, and even then many technical details might be closely guarded. But there are a variety of substances that are often a product of electronics manufacturing, and several demonstrate the complexity of making them in anything approaching an environmentally friendly manner.

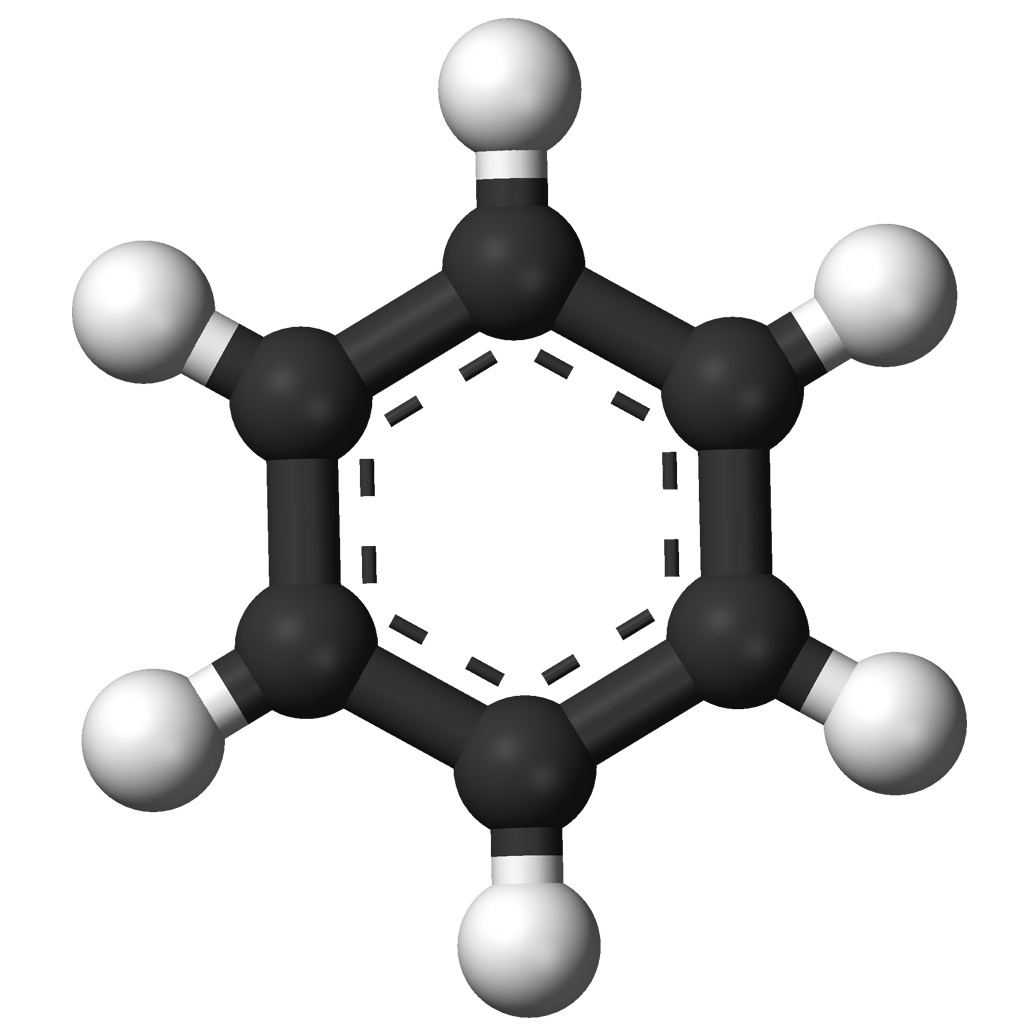

Benzene

Making electronics usually involves combining many small or very thin components that all need to be very clean. That’s part of the reason the industry uses so much water. It’s also why manufacturers use solvents like benzene, a common industrial cleaner and known carcinogen. Benzene also occurs naturally in crude oil deposits. A Wisconsin Department of Health Services notice warns that benzene leaks can quickly contaminate groundwater.

Foxconn has a history with benzene. Workers at Chinese factories owned by Foxconn and other companies have claimed that inhaling benzene fumes used to clean electronic devices caused them to develop leukemia. In 2014, Apple announced that it would require suppliers stop using benzene during the final assembly of its iPads and iPhones, but would allow its use in earlier stages of manufacturing.

Foxconn, which has repeatedly created controversy over poor working conditions and a series of suicides in its factories, has denied any link between leukemia and benzene in its factories, saying that even workers who were not exposed to the chemical developed this cancer. But it’s well established that long-term benzene exposure is dangerous to people.

Whether or not the planned factory in Wisconsin uses benzene or similar solvents, these past issues with Foxconn will invite scrutiny over working conditions, and highlight how environmental pollution is frequently connected to human health issues.

Copper

Copper is a common metal that’s found in just about every plant and animal on earth. It’s been used by humans for millennia, and remains essential in many industries.

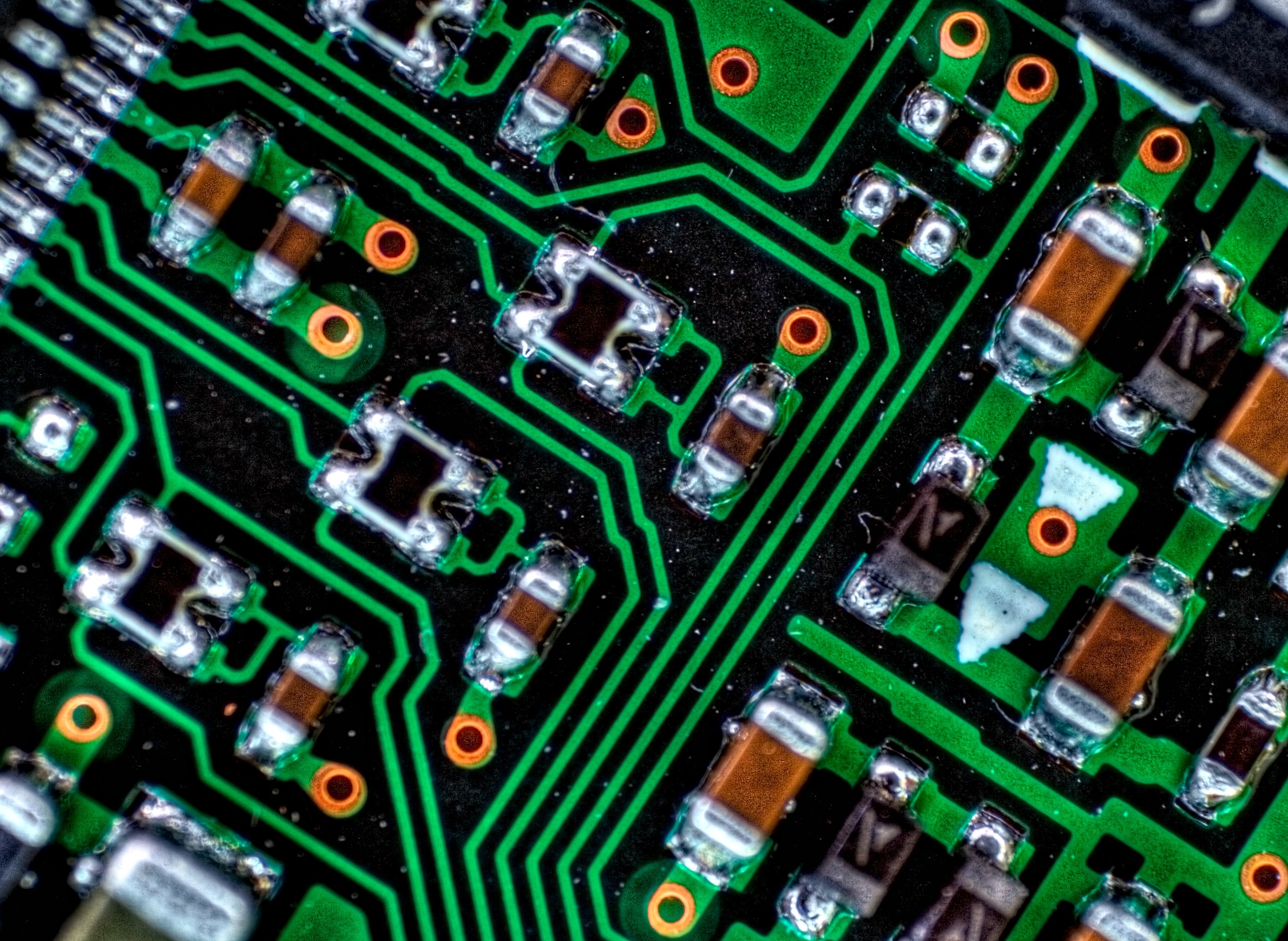

Depending on manufacturing techniques, copper is also used for quite a few components that are part of an LCD screen, from circuit-board etchings to small motors. But too much exposure to the metal — through inhalation, ingestion or skin contact — can cause health problems that range from minor issues like headaches and nausea to more serious matters that include kidney and liver damage.

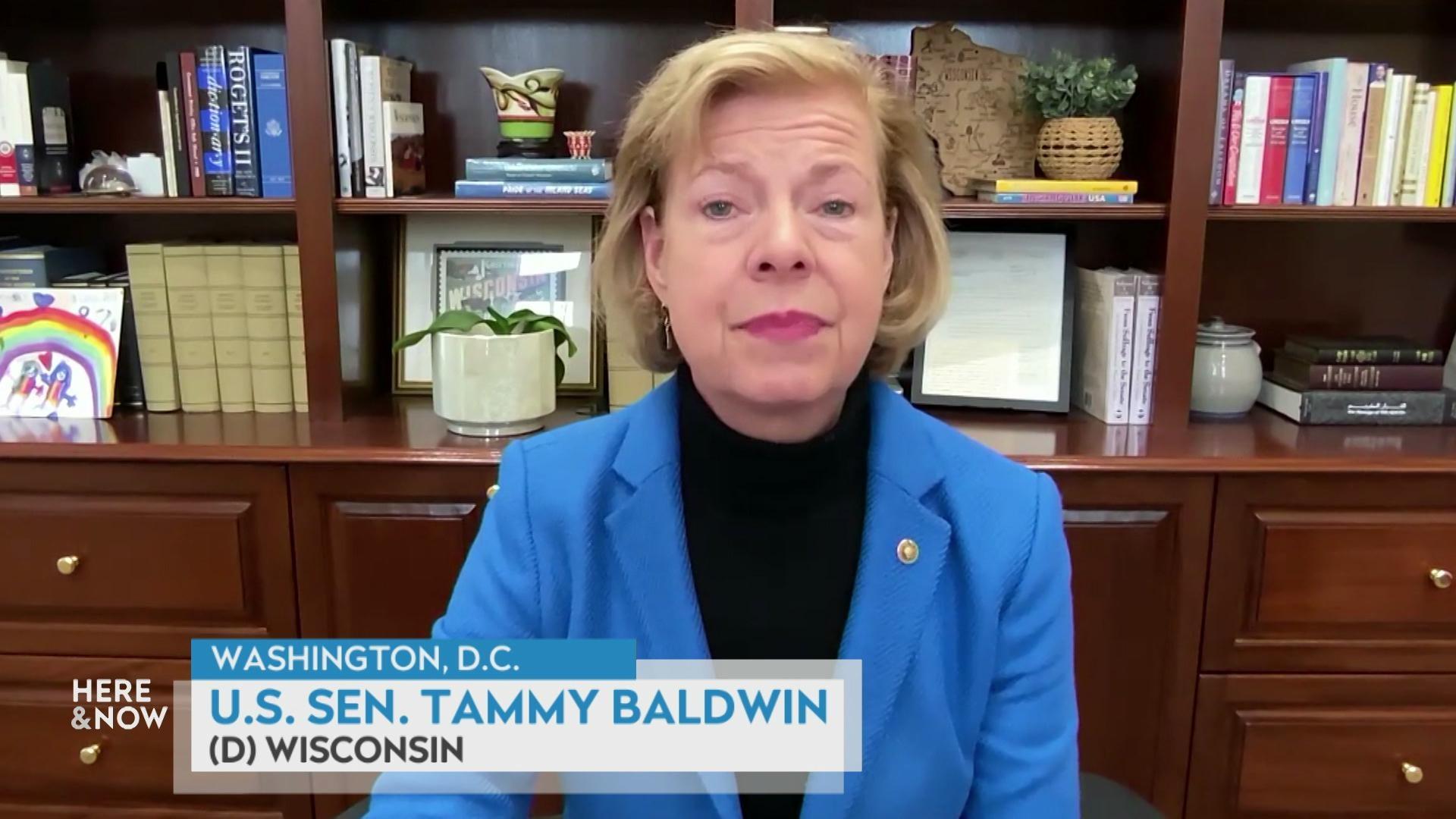

Copper is one of several heavy metals commonly used for LCD devices, with others including zinc, cadmium and chromium. University of Michigan professor of civil and environmental engineering Peter Adriaens discussed electronics manufacturing in an August 11, 2017 interview with Wisconsin Public Television’s Here & Now, and explained how problems arise with these metals when they don’t end up in the finished product.

“During the manufacturing process, the excess materials that are not used in the manufacturing would be stored into waste bins or waste drums and ultimately be processed off-plant,” Adriaens said. “The waste materials essentially are liquid materials. They usually get boiled down into a waste cake of materials … now the question is what Foxconn plans on doing with that.”

Leakage from the storage drums is “a fairly common occurrence,” he added. Moreover, Foxconn has been accused of dumping heavy metals into rivers in China.

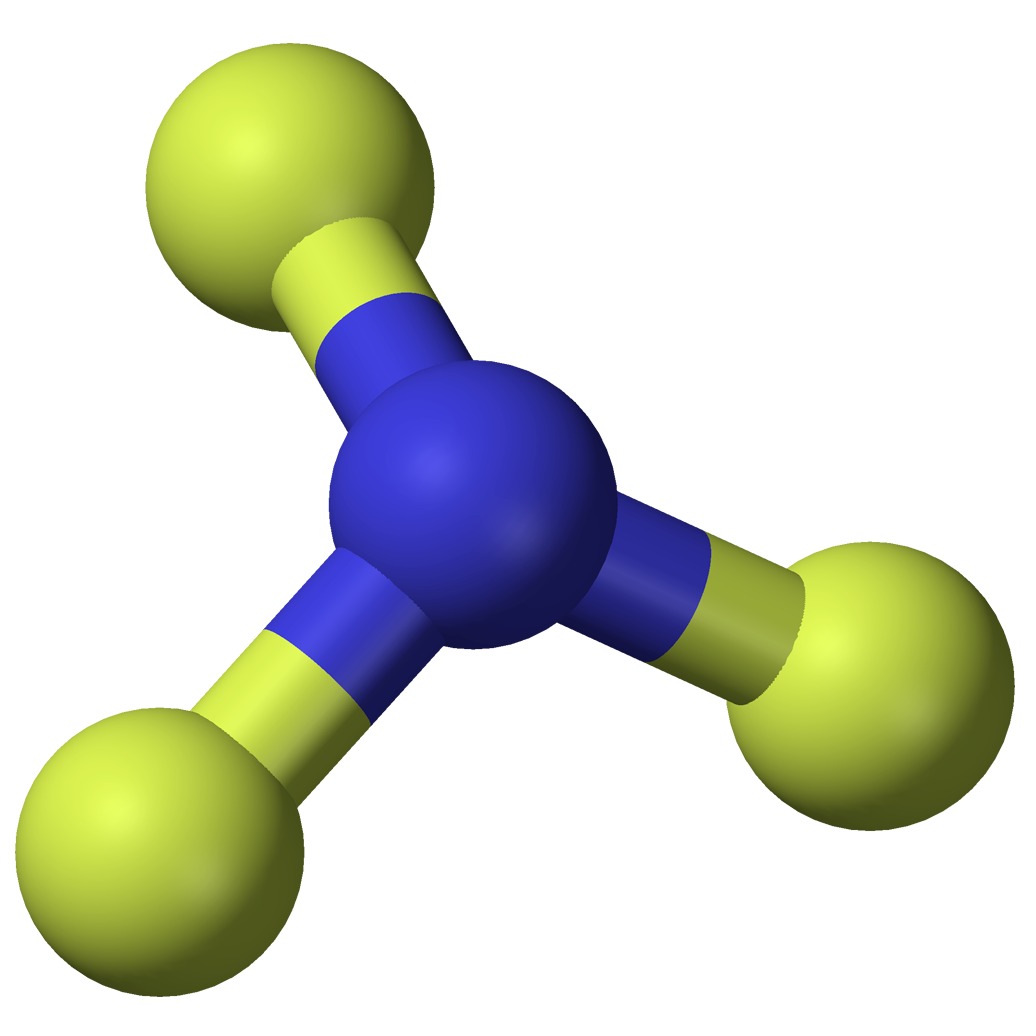

Greenhouse gases

Fluorineis used industrially to clean and treat surfaces to make them resistant to water and fingerprints. It can be obtained from nitrogen trifluoride, a synthesized chemical that is also a potent greenhouse gas. Nitrogen trifluoride comprises a tiny portion of these gases in Earth’s atmosphere, and over the years electronics manufacturers have adopted other methods of generating fluorine. Ironically, the electronics industry initially touted the chemical as a way to reduce its climate footprint.

But researchers say the level of nitrogen trifluoride in the atmosphere is still increasing, and that electronics manufacturing is the only known source. An August 2017 financial analysis suggested the market for the chemical was still growing, and noted LCD screens as one contributing factor.

Michael Prather,a professor of earth system sciences at the University of California-Irvine, sparked some public outcry and likely influenced industry efforts to reduce nitrogen trifluoride’s use with a 2008 studyabout the chemical. The study pointed out that, at the time, the gas was not covered by the international Kyoto Protocol and detailed its potential to become a major driver of global warming.

That hasn’t quite happened yet, Prather said in early August 2017, but there could be consequences if manufacturers don’t keep nitrogen trifluoride in check.

“It’s been growing quite rapidly,” he said. “If this becomes a big manufacturing issue, then it could add up.

In 2011, the United Nations addednitrogen trifluoride to its list of covered greenhouse gases.

Nitrogen triflouride and other fluorinated gases accounted for just three percent of U.S.-based greenhouse gas emissions in 2015, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. But American electronics manufacturing’s climate impact goes well beyond such gases. In 2015, U.S. carbon emissions totaled 6,587 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalents. Of that figure, about 6.3 million metric tons came from a relatively small number of electronics operations the EPA monitors.

When it comes to nitrogen trifluoride, Prather counsels caution but not alarm.

“It’s not something to go after but it’s not something you would ignore when making a plan for a plant or a factory,” he said. “There’s no reason to panic, but there’s also no reason to say, ‘Oh, no problem.'”

Indium

A relatively scarce element in the Earth’s crust, indium has a few possible uses in LCD screens and other devices. Indium tin oxide is often used as a coating for screens, and can be used to make transparent electrodes inside the glass layers of an LCD screen.

LCD manufacturing largely drives demand for indium, the U.S. Geological Survey notes, though it’s also used in photovoltaic cells. The metal’s compounds can be toxic, and people who have inhaled its indium tin oxide form in an occupational setting can contract a rare disease called indium lung.

Though indium tin oxide can present a hazard to workers exposed to it, the biggest environmental concern with the metal has more to do with economics. As a 2004 USGS commodity summary noted, indium is more abundant than elements like silver and mercury, but it’s found in mineral deposits, dominated by zinc ores, that are not necessarily cost-efficient to process.

“Indium is not ‘rare’ but deemed ‘critical,'” wrote Avtar Matharu of the University of York in an email, citing a 2010 report from the U.S. Department of Energy about materials in demand for clean energy technologies. “Indium is strategically important to the U.S. and many other global nations.”

A 2015 report by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory noted that indium supplies are “potentially fragile” given the metal’s relative abundance, ore processing methods and industrial production capacities. It concludes that there is not any “danger in ‘running out’ of indium,” but processing costs could reduce economic incentives for its use.

Indeed, the market for indium fluctuates, as detailed in the 2016 USGS commodity summary for the metal, and the U.S. is reliant on imports.

“Indium’s very important because the United States itself gets most of its indium from the Far East and Canada,” said Matharu.

There’s only so much indium recoverable in those locations, though, and manufacturers want to reduce their dependence on such sources by using recycled metals. It’s relatively easy to recover and recycle some of the metals found in an LCD screen, like steel, gold and palladium. It’s less common to recycle indium.

Researchers have developed various methods for recovering indium from discarded LCDs, like grinding up the glass it’s embedded in and dissolving this mixture in acid. But there are significant barriers to recycling the metal and making much money. It’s difficult to get ahold of very much secondhand indium, because people don’t know they can recycle their electronics, or simply store and forget them. People who do salvage electronics for their metals tend to go for the easy money, focusing on gold and silver.

“It starts becoming really expensive to recover that tiny amount of indium,” said Charles Anderson, a commodities specialist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

Foxconn did not return a request for comment. It’s not yet clear exactly which chemicals the company would use at its planned Wisconsin facilities or what practices it would implement to minimize human exposure and environmental releases. But given the general nature of electronics manufacturing, keeping things clean will be a big undertaking unto itself.

Editor’s note: This article was updated to clarify the etiology of indium lung and provide additional detail about the availability of indium.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us