Bad River Band Adds Voice To Concerns About Aging Line 5 Pipeline

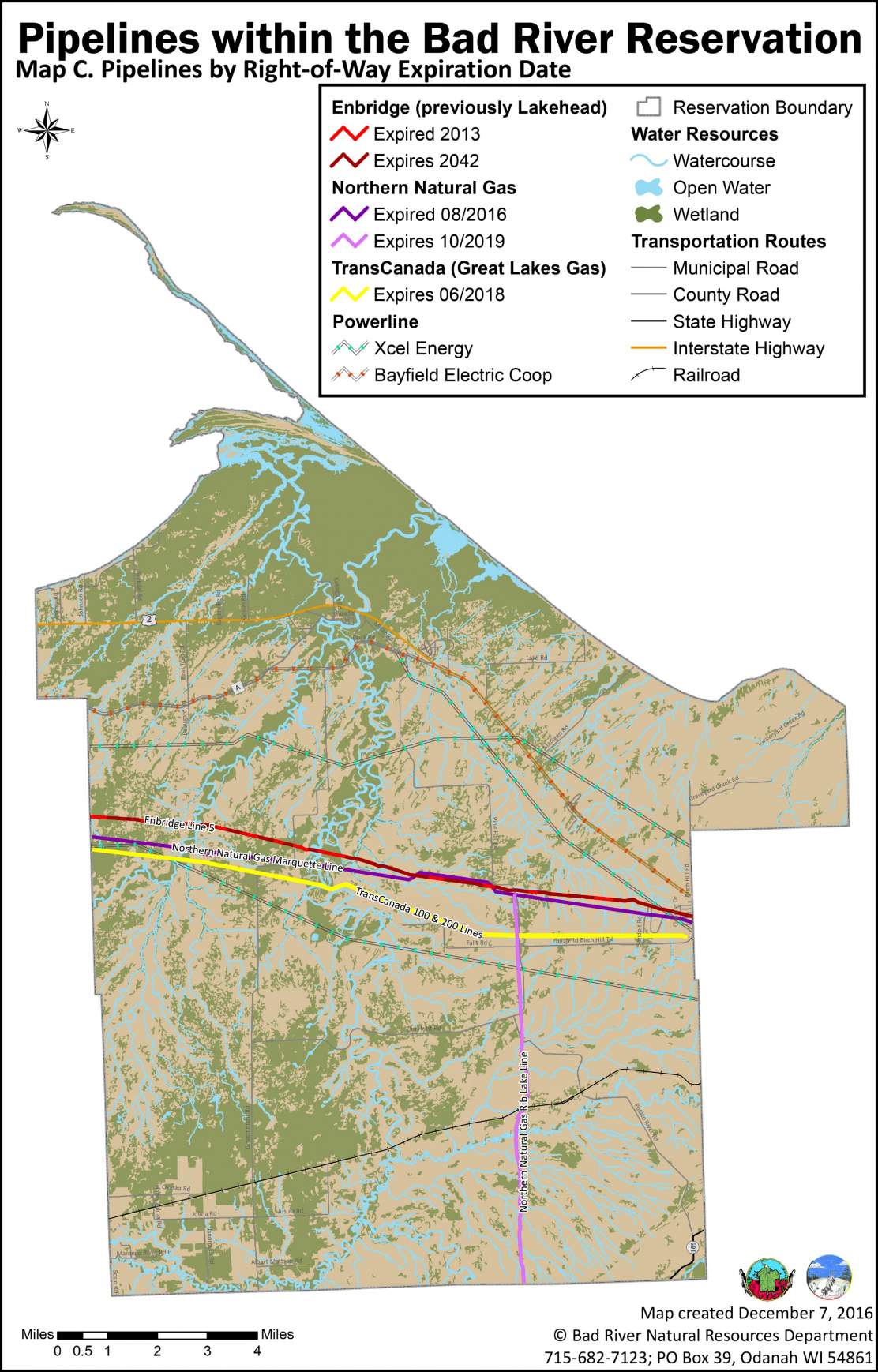

Five pipelines carry fossil fuels across the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians reservation in Ashland and Iron counties. While four transport natural gas, another carries crude oil.

January 20, 2017

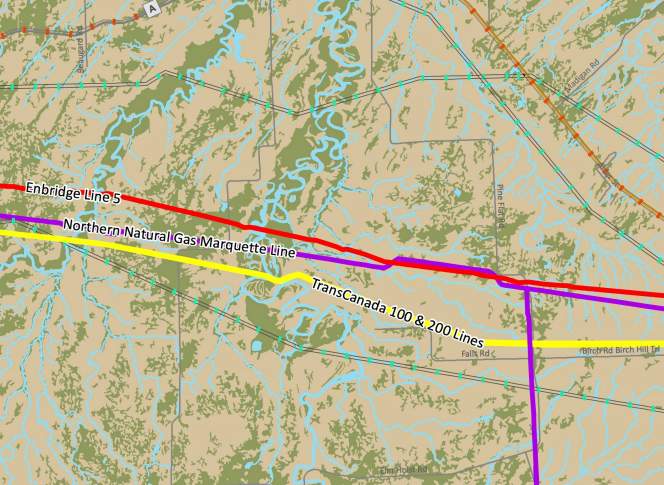

Bad River Reservation pipelines map crop

Five pipelines carry fossil fuels across the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians reservation in Ashland and Iron counties. While four transport natural gas, another carries crude oil. Owned by Enbridge Energy Partners, this latter pipeline is named Line 5.

Stretching 645 miles from Superior to Sarnia, Ont., Line 5 runs through a slice of northern Wisconsin, along the breadth of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and across the Straits of Mackinac separating Lake Michigan from Lake Huron. A total of 12.6 miles of Line 5 pass through the Bad River Reservation. Built in 1953, it’s by far the oldest pipeline in the reservation. As noted in a tribal government fact sheet, the next oldest pipeline there is the Northern Natural Gas Marquette Line, which was built in 1966.

It’s with age in mind that Bad River officials decided not to renew several of the property easements for Line 5 that allow it carry some 540,00 barrels of oil per day.

“That pipeline was given a life of originally 50 years,” Bad River tribal council vice chairperson Mike Berlin said in a Jan. 17, 2017 interviewon Wisconsin Public Radio’s Central Time. “That pipeline’s been in the ground now for well over 63 years.”

Berlin said that Enbridge has invested $100 million over the years in upgrading equipment along Line 5. However, he added that the company has conducted this work “without doing any upgrades to the pipe itself, to the pipe that’s in the ground. That bothers me.”

Berlin contrasted the Bad River Band’s relationships with Enbridge and another major energy company, TransCanada, which owns two natural-gas pipelines running through the reservation. Enbridge staff and Bad River Band staff are in touch, he said, but there isn’t a lot of person-to-person interaction. On the other hand, Berlin recalled a recent trip tribal council members made to Houston, where they spent an entire day working with TransCanada staff to review their pipelines, and attended a pipeline safety conference. He said TransCanada also recently sent a group of staff members to a tribal council meeting.

“When has this tribal council sat down with Enbridge?” Berlin said in the interview. “In the last three years that I’ve sat on the council, we’ve never yet had a conversation with Enbridge.”

An Enbridge spokesperson, Ryan Duffy, said the Bad River Band did not directly contact the company about not renewing the easements. Duffy said the pipeline is still operating, and would not speculate on how it might be rerouted if Enbridge had to shut down the segment of the line running through the Bad River Reservation. To further complicate the matter, some of the Line 5 easements on reservation expired in 2013, but others remain in place until 2042.

Berlin said the tribal council’s actions on this existing pipeline have “nothing to do with” resistance to building a new oil pipeline through the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in North Dakota. However, he said they’re motivated by a similar concern for drinking water quality. A spill from Line 5 would endanger the groundwater that serves as the Bad River Band’s main drinking-water source.

“If anything was to ever, ever happen, even if it was a minor spill versus a major spill, that would be a major catastrophe here on the Bad River Reservation,” he said.

The Bad River Band is hardly the first group to raise alarms about the age of Line 5 and its potential consequences in the Great Lakes region.

A retired engineer who worked on Line 5 in the 1950s told Vice in 2015 that the pipeline was meant to last 50 years. Environmental activists promoting a campaign called Oil and Water Don’t Mix, sponsored by the Groundwork Center for Resilient Communities in Traverse City, Mich., have also cited that figure.

Researchers at the University of Michigan are using computer models to determine what could happen if Line 5’s segments crossing the Straits of Mackinac spilled oil into the water. They determined that, in a worst-case scenario, oil would quickly spread along hundreds of miles of Lake Michigan and Lake Huron shoreline. The greatest impact would be in Lake Huron and along its northwestern shores.

In 2013, the National Wildlife Federation sent divers into the Straits to take a look at the pipeline, which is supposed to rest along the lakebed atop supports placed every 75 feet. They found that some supports were missing, which puts stress on the pipe. Underwater video footage showed long unsupported sections, and others covered up with debris.

Enbridge insists that it has maintained the pipeline properly. Nevertheless, environmental groups and legislators from both parties in Michigan are calling for Line 5’s segment in the Straits to be shut down.

Line 5 has spilled before. In November 1999 near Crystal Falls in the U.P., which is located about 15 miles north of Florence, Wis., the pipeline released 226,000 gallons of oil and gas. A 2015 report on Line 5, prepared by the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians in Michigan, tied that incident to the potential for a spill in the Straits of Mackinac. It concluded: “The Enbridge explanation for this breach is alarming to anyone who understands the conditions at the Mackinac Straits — that the pipeline was rubbing on a rock, which caused it to rupture.”

Another Enbridge line, 6b, was responsible for a 2010 spill into the Kalamazoo River in Michigan. Considered the largest inland oil spill in United States history, the repercussions from this incident continued for years, and informs the discussion in Michigan over Line 5.

Like other major infrastructure in the U.S., fossil-fuel pipelines are aging. More than half of the nation’s pipelines were built in the 1950s and 60s to meet the energy demands of the post-WWII economic boom.

Industry groups often quote a statement made by former National Transportation Safety Board chair Deborah Hersman at a 2013 U.S. Senate hearing: “If a pipeline is adequately maintained and inspected, age is not an issue.”

Additionally, industry publications like a 2012 report by the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America argue that data cast doubt on any correlation between aging pipelines and the incidence of spills — instead, they say there are more spills from older pipelines simply because there are more old pipelines than recently built ones. Still, even that report offers this caveat: “Older pipelines may be more susceptible to failure if certain kinds of threats are not assessed and mitigated. “

Passport

Passport

Follow Us