As Hits Pile Up, Badger Football Players Downplay Warnings About Brain Injuries

Wisconsin is in the middle of a national controversy about the health risks of contact sports, with research into concussions being conducted in the state, and a string of players who have left football after suffering brain injuries.

January 26, 2018

Wisconsin Badgers football game on Nov. 11, 2017

It was a freak hit — a blow to the back of University of Wisconsin Badgers fullback Austin Ramesh’s helmet by an opposing Illinois player. Ramesh described being “a little dazed” as he walked off the field.

He had suffered a concussion in Wisconsin’sOct. 28 matchupagainst Illinoisand ended up missing a week of practice and the next game against Indiana.

Ramesh, a senior who had gotten used to violent collisions going up against 200-plus pound linebackers, was dismissive of the injury. It sidelined him temporarily from one of America’s top collegiate football squads.

“I think it was just more of a precautionary thing more than anything. People take those things more seriously than anything these days, so it made my mom happy,” Ramesh said.

Interviews with more than a dozen current and former Badger football players reveal that many downplay the threat of brain injury, even though some said they have had their “bell rung” many times. Increasingly, however, a growing number of researchers, coaches, players and their families are worried — not just about brain injury in football but in other contact sports as well, including ice hockey, mixed martial arts, boxing, wrestling, rugby, lacrosse and soccer.

Wisconsin is in the middle of this national controversy, with research into concussions being conducted in the state, and a string of players who have left football after suffering brain injuries. A long-time UW-La Crosse head athletic trainer said he believes it is time for a #MeToo moment for concussions.

The problem is so serious that Dr. Bennet Omalu, the forensic pathologist whose discovery of chronic traumatic encephalopathywas recountedin the 2015 movie Concussion, recommends not letting children under 18 play any contact sports, including football.

Omalu, a volunteer associate clinical professor at the University of California-Davis, compared choosing to play football to deciding to abuse drugs.

In an interview, Omalu said even hits not deemed to be concussions can be dangerous. Every time there is a blow to the head, he said, the brain suffers microscopic injuries. The brain does not have a built-in capacity to repair these injuries, meaning such “subconcussive blows” can accumulate.

“There is no safe blow to the human head,” Omalu said. “Every impact to your head can be dangerous. That is why you need to protect your head from all types of blunt force trauma. A helmet does not make a difference.”

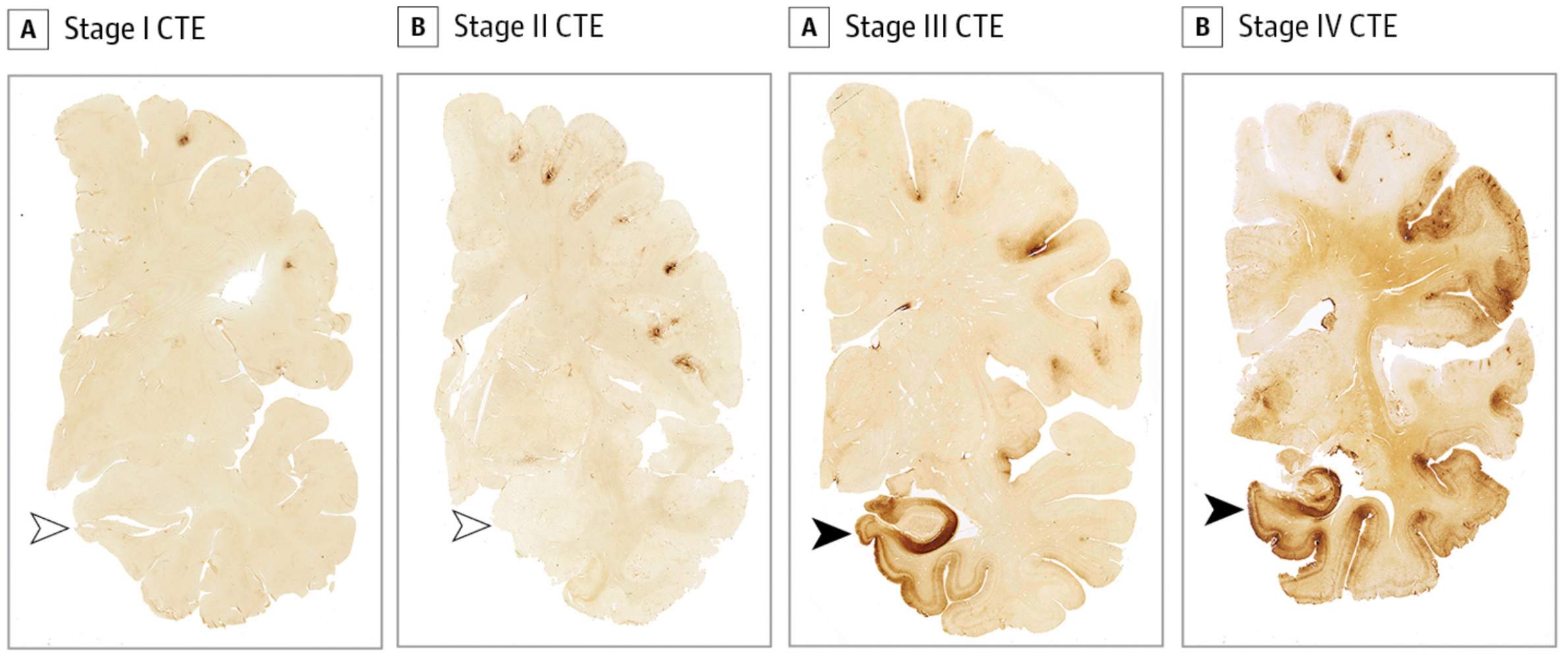

Research released in January 2018 from Boston University confirms Omalu’s worries about subconcussive blows. By studying the brains of deceased teenagers who had played football or other contact sports, researchers found that blows to the head — even if there were no symptoms of a concussion — can lead to the early stages of CTE, a degenerative brain disease. Signs of CTE were detected in the brains of three of the four research subjects.

“We’ve looked at the very earliest stages of this disease in teenagers, with the fingerprints of the neurodegenerative disease. It’s kind of staggering to even think about this — a teenager with a neurodegenerative disease,” said Dr. Lee Goldstein, associate professor of psychiatry at Boston University, in a video accompanying release of his research.

CTE has been linked to memory loss, impaired judgment and impulse control, aggression, depression, increased risk of suicide, Parkinson’s and dementia, according to the Boston University CTE Research Center.

Interviews with more than a dozen current and former UW-Madison football players show that despite concussion education programs mandated by the NCAA, some players describe staying in games after plays that left them temporarily disoriented.

In 2015, former Badgers linebacker Chris Borland rocked the National Football League when he quit the San Francisco 49ers after one year over fears of brain injury.

Borland, 27, told the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism that a scan has shown blood flow in parts of his brain is on par with a person in his 60s. Asked if the condition is reversible, Borland said, “Hope so. No one knows.”

The NFL has agreed to set aside a projected $1 billion for claims of former athletes suffering from brain injuries caused by concussions.

UW-Madison and the Medical College of Wisconsin are among 32 institutions participating in the Concussion, Assessment, Research and Education (CARE) Consortium, a $30 million study funded by the NCAA and the U.S. Department of Defense examining the nature and effects of concussion among 37,896 college athletes and military trainees. Another UW-Madison study looks at how students who have had concussions perform in the classroom.

Borland, others sound alarm

After being one of the NFL’s top rookies, Borland gave up his multi-million-dollar contract, telling ESPN that he was no longer willing to trade his health for money. In October 2017, Borland made a public service announcement on behalf of the Union of Concerned Scientists urging the public to not “sideline science” when it comes to important issues such as CTE.

After the 2015 season, three UW-Madison football players — Hayden Biegel, Arthur Goldberg and Walker Williams — decided to leave the team after suffering brain injuries. The UW-Madison Athletic Department said it does not keep a running total of concussions that players suffer, but does report individual concussions to the NCAA for the purposes of CARE study. The athletic department declined to make that data available.

Senior receiver George Rushing, who injured his leg in an offseason practice and left the team in November 2017, said the main problem he saw with UW’s approach to concussions is that some players ignored hits to the head as a way to get back in a game or return to practice more quickly.

NCAA schools including Wisconsin are required to have a concussion management plan that includes warning athletes about the dangers of concussion and following specific protocols when a player sustains a blow to the head. Student athletes are taught how to recognize concussions and are required to immediately report symptoms including amnesia, dizziness, confusion, nausea or fuzzy vision.

But a 2013 class-action lawsuit filed by current and former athletes against the NCAA argued those standards are too lax. A preliminary settlement requires the NCAA to set up a $70 million, 50-year medical monitoring program for college athletes, spend $5 million on concussion research and make rule changes to “identify concussions early and reduce the harm of secondary injury from returning to play before fully healed.”

‘Bell rung’ — but no concussion?

Although some players interviewed for this article said they are not concerned about concussions, several recounted their experiences in getting their “bell rung.”

Scott Doberstein, an athletic trainer whose career includes 16 years as UW-La Crosse’s head trainer, said the term is obsolete and misleading. Doberstein, who has been in the field for 30 years, said the terminology has been eliminated from medical literature for at least a decade.

“If you’re saying you got a bell ringer or dinged or dazed, it’s probably a concussion,” Doberstein said. “There’s no such thing as a mild concussion anymore, there’s no such thing as a bell ringer. It’s either a concussion or it is not.”

UW-Madison junior fullback Alec Ingold recalled his most recent concussion, which occurred in high school.

“Just the sound was really bothersome. All the lights were a little brighter, sound bothered me; you know, I got a little bit nauseous,” Ingold said. “I could tell right away that it was a concussion.”

For some of Ingold’s teammates, however, discerning whether they have had a concussion is more complicated.

Sophomore receiver A.J. Taylor, who claims to have never had a concussion, said, “I’ve gotten my bell rung plenty of times.”

He described the feeling as being “kind of dazed a little,” but added, “If you can get back up and play, then I think you’re good.”

“I don’t ever think about concussions,” Taylor said. “I don’t think about concussions or injuries and all that. I play and leave it to God.”

UW-Madison offensive lineman Beau Benzschawel and tight end Zander Neuville, both juniors, also attest to hits to the head, but they do not consider them serious enough to be called concussions.

“It’s almost like you’re a little dizzy,” Neuville said. “I guess for a little bit you’re just, ‘What just happened?’ and then you usually snap out of it and say, ‘All right, I’m fine.'”

For UW-Madison junior linebacker Leon Jacobs, these hits come with the territory and players need to “shake it off and do your job and do the next play.”

“You don’t really want to, like, say or do anything, you just have to walk off of the field or continue on to the next play,” Jacobs said.

Doberstein said such descriptions are indicative of potential concussions.

“Nowadays, if those athletes came to me with those kind of things, I would check them for concussion, rule it out, let them go back in,” Doberstein said. “But if I rule [a concussion] in, then they’re out. It gets pretty simple that way.”

According to Omalu, “bell ringings” are concussions. He emphasized that the real issue is repeated blows to the head, even if they are below the threshold of a concussion.

‘I signed up for this’

Throughout their careers, football players have been told not to play scared and to hit opponents hard. Now, though, they are being lectured: Protect your head.

For Michael Moll, assistant athletic director of sports medicine at UW-Madison, and his staff, this is the battle they wage every year: Trying to get student athletes to absorb and heed the warnings about concussions. The messages are conveyed in handouts, online education and in-person presentations from the Sports Medicine office.

“They kind of turn themselves off to it,” Moll said. “They’ve already heard it. I think that’s a little bit of a challenge.”

Asked if he was aware of the latest studies about concussion, UW-Madison cornerback Nick Nelson, a junior, said, “I don’t pay attention to that. I stay away from that.”

Jacobs, the linebacker, noted that other sports, such as boxing, have risks.

“I mean, we know what we’re getting ourselves into so that’s not something I think about … They give us a lot of resources and stuff,” Jacobs said. “But like I said, I don’t pay attention to a lot of that because if it happens, it happens. I signed up for this, so I know what I’m getting myself into.”

For some, the lure of playing football at a high level now far outweighs the warnings about potential brain damage in the future.

“I look at it as you can just get a concussion just walking down the street,” said UW-Madison cornerback Derrick Tindal, a senior. “I don’t know how the brain works, and I don’t know what’s going on. But as far as it slowing me down, no. I’m going to be playing at a high speed and go make plays.”

The culture of denial surrounding concussions in football locker rooms runs very deep. For Doberstein, it almost gave him a black eye.

Fifteen years ago, while head athletic trainer at UW-La Crosse, a tight end had been diagnosed with a concussion during a scrimmage. In explaining the situation to the athlete’s father, things got heated.

“He got all red, he clenched his fists and he said, ‘I don’t need to hear this,’ and I said, ‘Sir I’m sorry but we’re going to protect your son the best we can,'” Doberstein said. “It was surreal that I had to deal with that from a parent who wanted their kid to play despite a concussion.”

Doberstein said it will take a drastic shift in football culture to take concussions more seriously.

“Look at all of the sexual harassment stuff that has been under the carpet and the #MeToo stuff. We need something like that for concussion. We need people to come out and say, ‘This is not good. We shouldn’t be hiding it,'” Doberstein said.

Evidence of harm mounting

In November, researchers announced they may have found a way to diagnose CTE in a living person. The team was led by Omalu.

Previously, diagnoses have been based on autopsies. In this case, a scan of the brain of Fred McNeill, a former Minnesota Vikings linebacker, showed signs of the devastating brain disease before he died in 2015. The finding could create even more momentum to diagnose and prevent concussions in football.

That pressure is already high. Another study published in July 2017 showed CTE in 110 of 111 deceased ex-NFL players who had donated their brains to research. In the same study, 177 of 202 deceased players who had played at any level of football — high school, college or the NFL — were found to have CTE.

Former New England Patriots tight end Aaron Hernandez, who played three seasons in the NFL, took his own life last year while incarcerated for a murder conviction. Hernandez had the most severe known case of CTE for someone his age, according to doctors at Boston University.

Initial research points to longer recovery

At UW-Madison, the CARE Consortium study is exploring the effects of blows to the head — even those in which an athlete has exhibited no symptoms, said Dr. Alison Brooks, an associate professor in the Department of Orthopedics and the principal investigator at the Madison site.

This entails comparing medical imaging, blood work and data from sensors worn by football, soccer, lacrosse, field hockey, ice hockey and rugby athletes who have suffered a concussion. Those results are paired with another player who plays that same contact sport but has not suffered a concussion, said Brooks, who is a team physician for UW-Madison athletics. Those two athletes’ test results are then compared with an athlete in a non-contact sport, she said.

Early indications point to a longer recovery period being needed for athletes who suffer concussions, said Dr. Michael McCrea, a professor and director of brain injury research at the Medical College of Wisconsin who is one of the study’s principal investigators. Initial findings are expected to be published in the first half of 2018, McCrea said.

Currently, players are held out until they are symptom free, then another week is added. During the time after symptoms have disappeared, McCrea and Brooks said, athletes gradually return to normal sports activities. But McCrea said an athlete may report being symptom-free and may seem healthy, while the brain itself is still not fully recovered.

Brooks added that the study “probably” will find that longer recovery periods are needed.

Using in-helmet sensors, researchers also have realized that concussion is a very individualized injury.

“Some athletes might get a concussion on a relatively low 50 G hit when some athletes are repeatedly taking 80, 90 G hits and not getting concussed,” Brooks said.

“The magnitude of those impacts I can tolerate is probably different from you,” she added. “I think that is what some of the early analysis of the head impact data has shown. It is individual specific.”

Omalu, however, is skeptical of any medical research coming from an athletic organization.

“If they have the money, they should give the money to independent researchers,” Omalu said. “Medicine is not an absolute science. Medicine is not like math or physics. In medicine, you can cook the books and come up with the results you want to come up with.”

Borland, who participated in the CARE study, is also doubtful the research will lead to meaningful insight and change.

“The athletes involved in the research were a smattering of starters, reserves, and in some cases players who were out for the season with injuries,” Borland said, reflecting on his own experiences. “This research is no way representative of the realities and dangers of playing high-level football.”

Borland believes the study’s focus on diagnosed concussions also will not account for subconcussive hits, which have been found to have negative effects on the brain. Nor will it yield the true number of concussions in the sport, given estimates developed by researchers in 2014 that less than one in every 20 concussions is reported by college football players.

When it comes to the education the players receive, which is crucial in making sure all concussions are reported, Brooks believes the NCAA is focused on student welfare but more must be done.

“What is currently required, the little fact sheet and the ‘Yeah I read it signed my name’ that they have players and coaches do is woefully inadequate in terms of really educating players,” Brooks said.

The study’s overall goal is to make contact sports safer and to mitigate the effects of concussions. Those answers may not come for years.

“I think our current student athletes are going to help us get those answers,” Brooks said, “but it might be their children that reap the benefit of those answers.”

Omalu does not believe football can ever be made completely safe.

“Let me ask you, can you make fire safer? I suppose you could make it safer by putting it in a lighter,” Omalu said. “A lighter is safer than a match stick, right? But would you give your 5- year-old child a lighter to play with?

“They say they can make it safer. They can’t make it safe.”

School work, concussions studied

Another study at UW-Madison is exploring the effects of concussions on high school and college students’ academic performance. Traci Snedden, an assistant professor in the UW-Madison School of Nursing, is leading the research, which began with 60 UW-Madison students who had suffered concussions under a variety of circumstances, such as while playing sports, falling on the ice or in a scooter crash. It has been expanded to high school students in the Madison and Milwaukee areas.

Snedden said students reported problems including, “Difficulty taking notes and listening to their professor at the same time, difficulty following along, needing extended time to complete their projects due to headaches, having struggles when they work in bright classrooms or classrooms with high stimulation, a lot of people, a lot of noise.”

Students’ school work suffers much more after they experience concussions than after other types of injuries such as fractures and strains, Snedden said.

“Even when comparing to those musculoskeletal injuries, the college-aged students with concussions had significantly more effects of academic struggles in the classroom,” Snedden said.

Like Moll, Snedden is not surprised student athletes are in denial about the dangers of concussions.

“It is once again going back to the culture of the sport, the culture of concussion, that we still have some work to do,” Snedden said. “I truly do believe the players are receiving timely and accurate information, but how they process that is an intellectual and culturally related phenomenon.”

Efforts to reduce concussions uneven

Ingold, the UW-Madison fullback, sees reason for optimism. He believes football is safer today, thanks to curtailed practice schedules and new strategies to avoid helmet-to-helmet contact.

“I feel like those studies are really important to show how the game was,” Ingold said. “I feel like there’s going to be changes in those results maybe when you get some of the newer guys who have been playing tackle football forever and everyone’s telling you ‘Keep your head up’ and no more two-a-day [practices].”

Heads Up Football is an initiative by the USA Football national youth program to teach players safer tackling techniques. Both USA Football and the NFL claimed the initiative, which started as a pilot program in 2012, lowered the amount of concussions in youth football. But the New York Times, in its own review of the datain 2016, found the program had “no demonstrable effect on concussions.”

Many are still hopeful other recent changes will reduce concussive hits. Those changes include penalties in college football against targeting, which includes helmet-to-helmet hits.

“I think the biggest reduction we’ll see is in how people tackle, in how they practice, how they compete in games, and I think you’re going to see a larger reduction [in concussions] in football due to how people play the game,” said Moll, UW’s assistant athletic director. “Certainly the example of the targeting penalty and targeting rules lend at least some enforcement to the idea that it is not okay to make that direct head-to-head contact.”

Another possible solution some point to is the continuing improvement in equipment, especially helmets.

“We keep taking the head out of the game, and then if the equipment … is properly fitted, I think the guys in today’s game can play without concussions,” UW-Madison running backs coach John Settle said.

But even within the UW-Madison team, the idea that better equipment is the answer is debated. Asked whether better helmets can reduce concussions, Moll said, “I don’t think that is the case. … Helmets were designed to eliminate skull fractures. They’re not designed to eliminate concussions.”

A brother’s loss

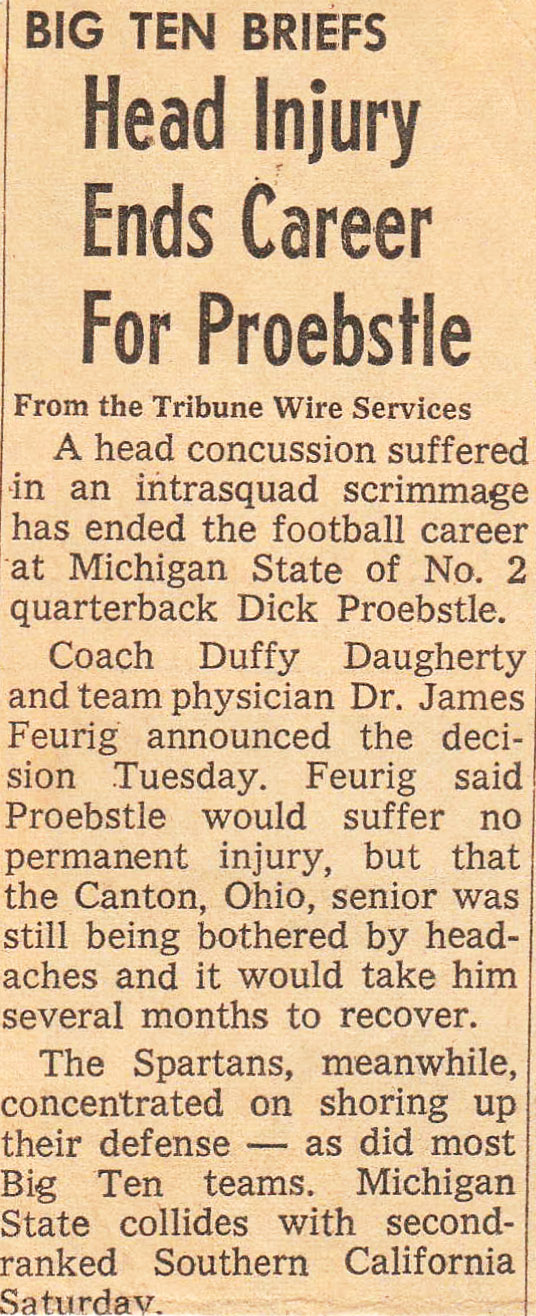

Jim Proebstle, a former college football player, has seen the devastation of repeated concussions in his own family. His older brother, Dick Proebstle, who played alongside him at Michigan State, died in 2012 at the age of 69 after suffering from CTE.

A severe concussion ended Dick’s playing career at Michigan State in 1964. Later, intense migraines forced him out of law school, and Dick’s life began to unravel because of anger, poor decision-making and depression, Jim Proebstle said.

Proebstle, who now lives in suburban Chicago and northern Minnesota, said he realizes the erratic behavior that led his family to pull away from Dick was caused by blows to the head beginning when he was a young player.

“It’s very sad,” Proebstle said. “Particularly when you look back and you sort of judge yourself for being angry with Dick. You ask yourself, ‘Why couldn’t I have seen early on that there was something wrong?'”

In 2015, Proebstle wrote a book, Unintended Impact, chronicling his brother’s struggles with what was later discovered to be CTE.

“One of the reasons I wrote the book is people talk about concussions, but when you’re 18 or 20 or 22, it’s hard to picture what the devastation from concussions looks like 30 years later,” Proebstle said.

Football is a game of toughness. The drive to play through injury and help the team can get in the way of concussion prevention, Brooks said.

Athletes who hide concussions, however, may end up missing more time than if they had reported the concussion right away. According to Moll, athletes return to play earlier when they report the concussion.

Senior receiver Jazz Peavy has received that message. Peavy left the program for undisclosed personal reasons after being with the team for the past three seasons and playing briefly in 2017.

“From what I know, if you get a concussion, it is a lot worse if you don’t take care of it and you keep on doing the same thing,” he said.

Others are resigned to the danger.

“I’ve been playing tackle football since I was five,” Rushing said. “Whatever damage is done is done at this point … I feel like everybody who plays this game knows it comes with the risk. So if you can’t accept that, I respect you for not playing the game.”

Proebstle knows how thrilling it can be to play Big 10 football. He was starting tight end on Michigan State’s National Championship football team in 1965. But Proebstle wants today’s players to take a longer view — towards their lives after football.

“The vast majority of the people playing on the Wisconsin team, they’re not going to be playing football in four years. They’re going to be getting jobs, getting married, you know, all the things that we all do,” Proebstle said.

“And you really don’t want to be dealing with the byproducts of a concussion when the prime of life and your career are just starting to take hold. You just don’t. And I don’t know how to get that point across to a player without scaring the crap out of them.”

Luke Schaetzel, a recent University of Wisconsin-Madison journalism graduate, is a freelance reporter based in Madison. Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism managing editor Dee J. Hall contributed to this report. The nonprofit Center collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates. The Center’s collaborations with journalism students are funded in part by the Ira and Ineva Reilly Baldwin Wisconsin Idea Endowment at UW-Madison.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us