Amid Turmoil, Cybersecurity Remains Concern Of Wisconsin Elections Officials

When it comes to elections in Wisconsin, just about everything seems to be growing more complicated.

February 7, 2018

Three voters at polling place on UW-Madison campus in November 2016

When it comes to elections in Wisconsin, just about everything seems to be growing more complicated. From ongoing court battles over voter ID and redistricting to administrative battles over agency leadership to the fundamental matter of organizing the nearly 2,000 election officials in place around the state, it can be hard to follow what’s happening with its electoral system.

When reports of attempts by Russian hackers to break into state election systems emerged in 2017, the challenges to Wisconsin’s election system grew even more complicated and cybersecurity practices were called into question. While state officials remain confident that Wisconsin’s elections are secure, the threat of hacking remains.

The Wisconsin Elections Commission oversees nearly everything election-related in the state, from the machines used to count votes, to preparing for worst-case scenarios on Election Day. In 2018, the commission has been embroiled in controversy over its leadership. After Republican leadership in the state Legislature called for commission administrator Michael Haas to resign, the state Senate refused to confirm him for the job. However, the commission subsequently voted to retain him is in this position on an interim basis.

The commission is also tasked with elections security. University of Wisconsin-Madison political science professor Barry Burden discussed this role of the commission in a Jan. 26, 2018 interview with Wisconsin Public Television’s Here & Now.

“The intelligence community has said the Russian government is interested in meddling in American elections, maybe favoring one side, but mostly just trying to cause some turmoil,” Burden said.

As a non-partisan body, Burden said the commission is in a unique position to guide election best practices across the nation, in terms of security and beyond.

“Wisconsin had been a state that had been held up as a model of good government when it comes to elections,” Burden said. “Most states have a partisan elected secretary of state who runs elections. That’s true in probably over 40 states. Some states have also boards of elections, but those can have a partisan taint as well. Both the Government Accountability Board and these commissions that followed afterward are either nonpartisan or bipartisan, had been viewed around the country as a model for how to run elections that emphasize expertise, continuity and independence in a way that other states have not.”

A tale of two systems

Whatever the status of Russian hacking attempts on elections systems across the United States, the Wisconsin Elections Commission is working to ensure that Wisconsin’s elections are secure.

When it comes to understanding election cybersecurity in the state, there are two key tools at play, commission spokesperson Reid Magney explained. The first is the state’s voter database, which stores legally required information on all registered voters. The second is the system of machines that actually count and collect ballots.

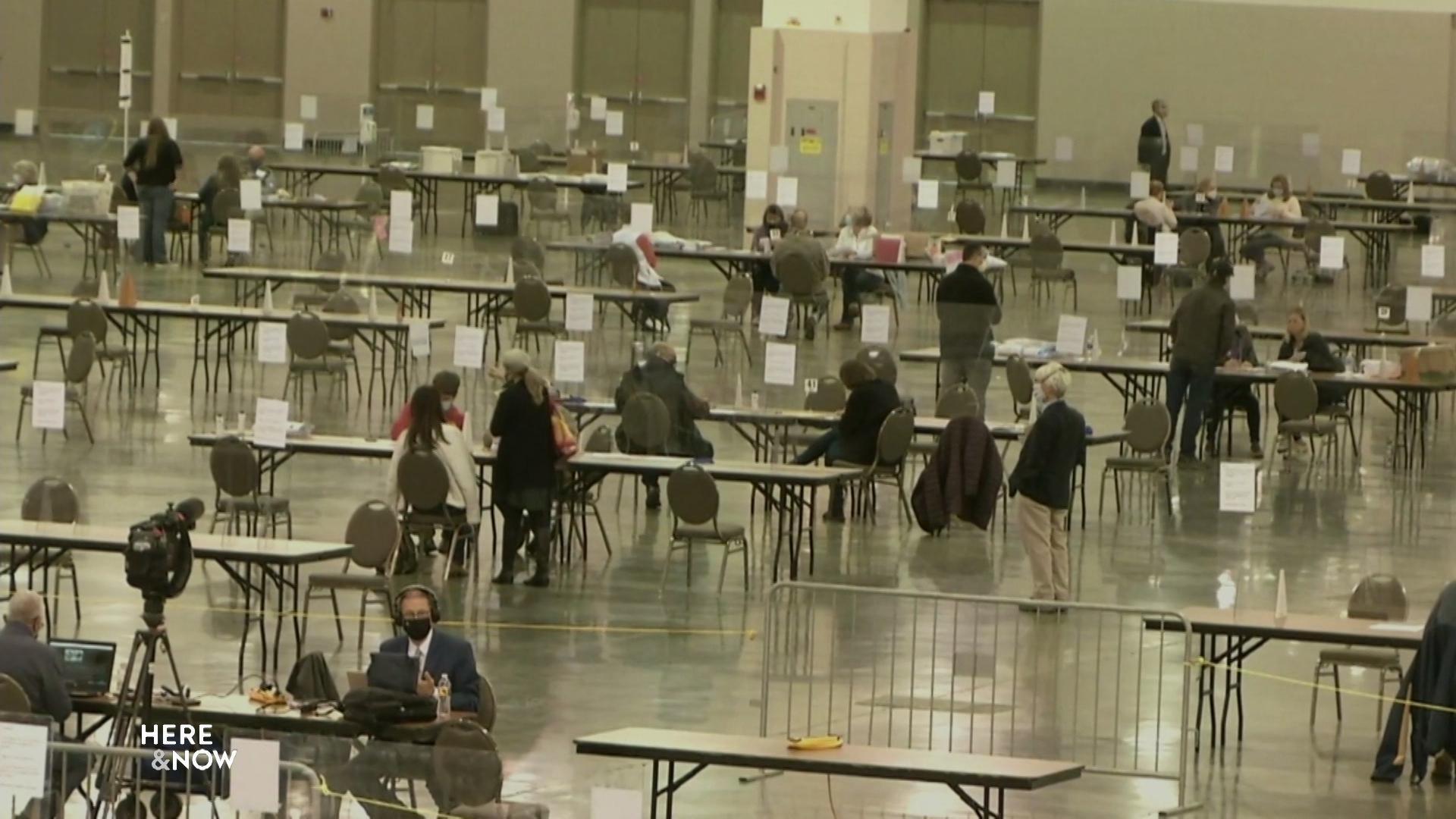

Wisconsin uses a centralized voter data system, meaning that all voter data are stored in one database: WisVote. Thousands of elections officials in 700 different municipalities across the state have access to WisVote, from county and municipal clerks to local volunteers. While having a vast amount of personnel working to run elections can be helpful, it also opens the door to additional challenges and risks.

Since the implementation of WisVote in 2016, the commission has taken several steps to ensure its digital security, Magney said. The first layer is all data stored in the system is encrypted, meaning even if anyone got ahold of it, it’s less likely this information could be used. The commission is also working with the Wisconsin Division of Enterprise Technology to implement a multi-factor authentication process for elections officials across the state who access WisVote. This practice, however, is where having hundreds of partners becomes a challenge.

Election officials across the state have varying access to technology, Magney explained. Some users don’t have high-speed internet access and are forced to rely on county clerks for help. Using a multi-factor authentication system requires the user to provide a secondary login (usually a numerical code) in addition to their typical username and password. These codes are typically sent via email or text message, making it difficult for users without broadband to log in.

“In Wisconsin, the elections are really run on the ground by the 1,853 local clerks in the state,” Magney said. “From as big as the Milwaukee Elections Commission [and] the city of Madison Clerk, down to a town clerk up in Bayfield County who does the work on her kitchen table with a computer that’s 10 years old.”

A multi-factor authentication process would provide another safeguard against potential hackers, but it has yet to be implemented.

When it comes to election security, protecting the voter database is only half the battle, Magney said. The other half comes down to the system that collects and counts ballots. Unlike Wisconsin’s voter registration system, the use of voting equipment is highly decentralized.

The state purchases voting equipment from multiple vendors and the machines themselves are not connected to the internet, meaning that there is no single place where ballot information is stored. This decentralized system, Magney said, is a great strength when it comes to cybersecurity.

In addition to municipalities around the state, the Wisconsin Elections Commission works with U.S. Department of Homeland Security to craft election security plans. For the past year, Homeland Security has run “cyber hygiene” scans of Wisconsin’s election system to find any vulnerabilities. There are plans for the state commission to work even closer with the federal department in the future.

Haas has security clearance to attend classified Homeland Security briefings, though has yet to receive any, Magney said.

Burden told Here & Now that this level of clearance is unique, for the time being.

“Haas has gotten this special clearance to be involved in those discussions at a higher level of security,” Burden said. “If he’s gone, there’s then no one available in the state to have those conversations. I suppose someone else, maybe a replacement administrator, could get those clearances, but you’d have to find someone you trust, who’s going to be a stable force at the top of the agency. Right now stability is not the thing that is happening.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us