After 5 Years, White-Nose Syndrome Is Devastating Wisconsin Bats

A handful of North American bat species that were once common in Wisconsin are possibly heading toward extinction, or at least disappearance from the state.

By Will Cushman

October 30, 2019

Hands holding northern long-eared bat in Illinois

A handful of North American bat species that were once common in Wisconsin are possibly heading toward extinction, or at least disappearance from the state.

That bleak trajectory is more apparent than ever five years after a fungal disease that experts consider globally unprecedented first appeared in Wisconsin. Known as white-nose syndrome, the disease has killed millions of hibernating bats across eastern North America over the past decade. In the last few years, it has swiftly wiped out at least one of the species that have flown through Wisconsin’s woods and roosted in its caves for millennia.

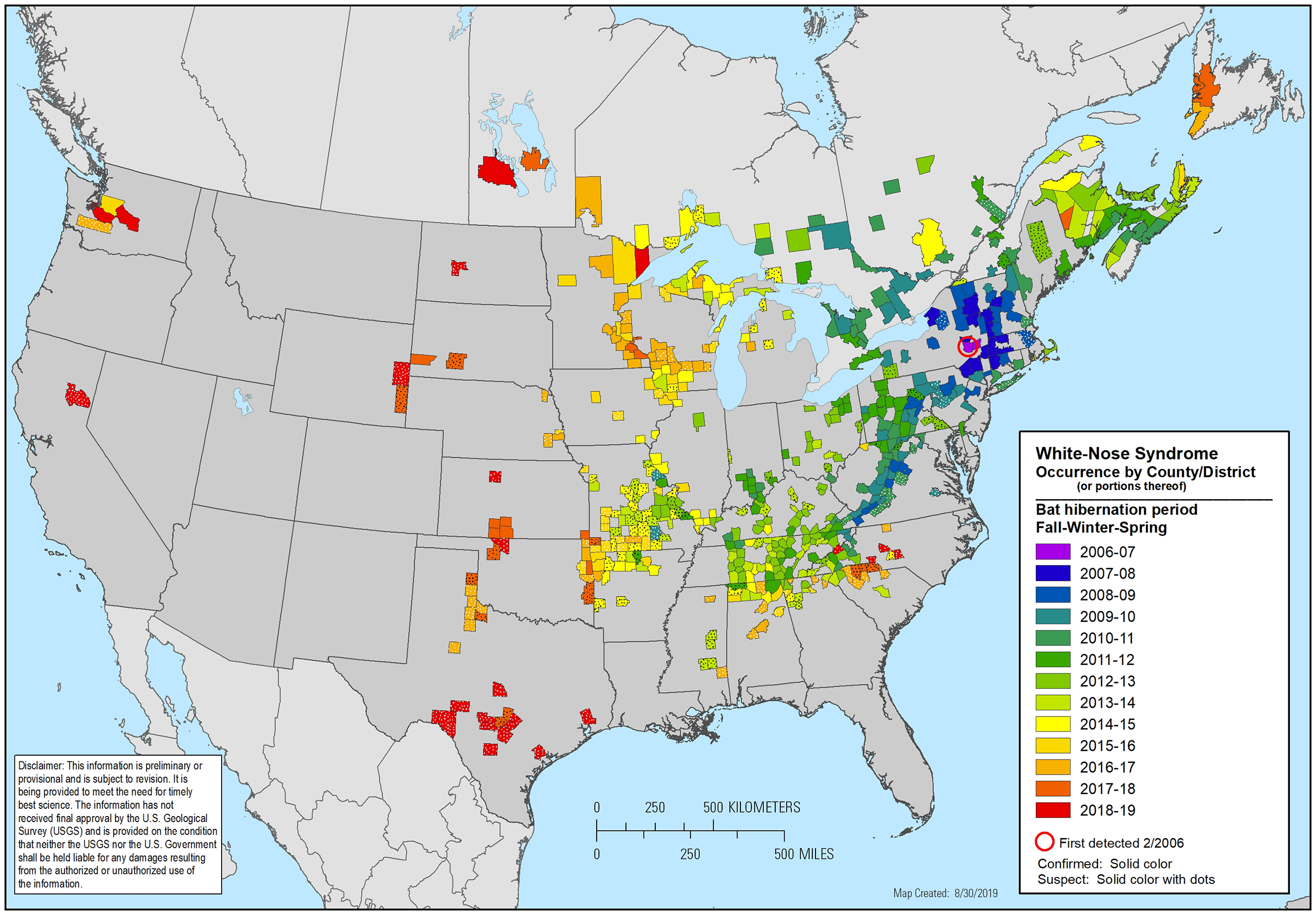

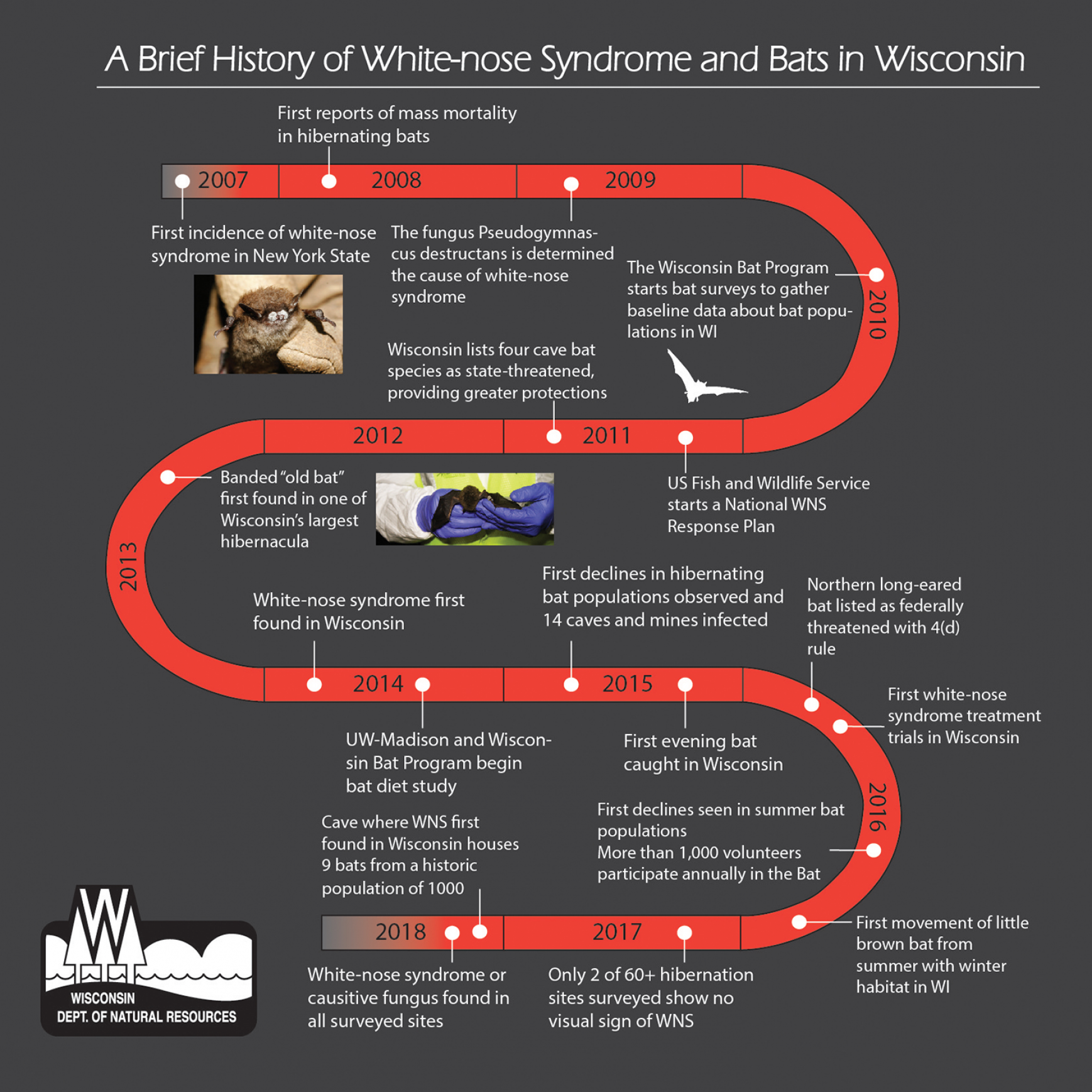

White-nose syndrome is caused by an invasive fungus that scientists believe to be native to Eurasia and was likely introduced to North America in 2006. The following winter, bats hibernating in caves popular with tourists near Albany, New York, were observed with a mysterious, powdery white fungus on their skin and subsequently began dying in large numbers. The fungus was prominently visible on the bats’ muzzles, and soon “white-nose syndrome” became the standard term to describe their malady.

Despite efforts to control its spread, the disease-causing fungus has pushed steadily west, and in 2014 it was discovered at a bat hibernation site in Grant County, in Wisconsin’s southwest corner. Sites where bats hibernate, including caves, mine shafts and buildings, are called hibernacula. As of May 2018, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources had confirmed the presence of the fungus in at least 25 of Wisconsin’s 28 counties with known bat hibernacula, mostly in the state’s southern and western regions.

Wildlife managers and health specialists in Wisconsin are now at the center of a continent-wide endeavor to understand how a fungus that’s benign in Eurasian bats is capable of obliterating their otherwise healthy North American counterparts. They’re also racing to identify ways that the newly vulnerable bat species could be spared extinction.

A destructive fungus with global significance

Pseudogymnoascus destructans is a cold-loving fungus and grows best at the cooler end of a range from about 39-65° F. (The fungus won’t grow at temperatures above 68° F). Unfortunately for North America’s hibernating bats, this temperature range aligns with the conditions found within their dark wintertime abodes.

In Wisconsin, these hibernating species are the big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus), little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus), northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis) and tri-colored bat (Perimyotis subflavus). Populations of all but the big brown bat are declining precipitously in the state, and scientists are confident that P. destructans, named for its destructive power, is to blame. They weren’t always so sure.

“When this disease emerged in bats, even though this fungus was growing on them, there were people that thought maybe the fungus wasn’t the primary cause [of the disease], and that it was just sort of another symptom of what was wrong, rather than the cause itself,” said Jeff Lorch, a microbiologist at the United States Geological Survey.

Lorch studies wildlife diseases at the National Wildlife Health Center, which is located in Madison. The health center receives specimens from across the nation of wildlife that have succumbed to various diseases. It was scientists there who in 2009 first identified and described P. destructans found covering the bodies of bat specimens sent from the East Coast.

At the time, years before the fungus would be found in Wisconsin’s wild bats, Lorch was a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Figuring out how P. destructans was infecting and killing North American bats became the focus of his PhD work.

“At the time, people didn’t really know that fungi would serve as primary pathogens of healthy mammals,” Lorch said. “There were a lot of people that didn’t necessarily believe that this fungus was the cause of white-nose syndrome.”

In a lab setting, Lorch exposed healthy captive bats to the fungus, and they quickly developed the classic white-nose syndrome infection. With the use of a genetic technique called polymerase chain reaction, known as PCR, Lorch was able to say definitively that P. destructans was the only species, fungi or otherwise, involved in the disease.

That discovery represented the first time that a fungus was implicated in a disease that kills otherwise healthy mammals.

“In mammals, we typically think of fungal diseases as being more opportunistic,” Lorch said. For instance, usually only immunosuppressed humans are at risk of developing a serious fungal infection.

How a skin fungus can be so deadly

In the case of white-nose syndrome, the current theory is that bats likely become exposed to P. destructans spores while flying or roosting within a cave or other hibernaculum that has become contaminated with the fungus. The spores then germinate on the surface of the bats’ skin, which is extremely thin in places such as their wings. Beneath this thin skin is a layer of stretchy collagen that helps give bat wings their elasticity.

The fungus grows through the skin and can invade that underlying collagen, researcher Jeff Lorch said, though it doesn’t penetrate deeper into the bats’ small bodies.

“This isn’t an infection that goes down into the liver or lungs or anything like a deep fungal infection,” Lorch said. Initially, he added, this observation was one reason some scientists were skeptical that a fungus was the true cause of the disease; it went only skin deep and seemingly did not impact vital organs.

However, Lorch said that bats’ very thin wing skin likely provides many more physiological functions than simple elasticity.

“Since bats have such a large amount of their surface area dedicated to their wing skin, there’s probably certain physiological processes that the skin helps them perform during hibernation,” he said. These roles could include exchanging oxygen or carbon dioxide, or serving as a barrier for water loss during hibernation.

The implication is that what may appear as a simple skin infection may actually disrupt fundamental processes that keep bats healthy while they hibernate.

“If you start compromising the surface of that skin, it also might affect these physiological processes,” Lorch said.

Another more obvious physiological disruption with potentially fatal consequences for hibernating bats is the disruption of their actual hibernation, or torpor. Even healthy hibernating bats arouse from their hibernation about once a month to excrete urine and other toxic metabolic byproducts.

“But what we’re seeing in some of our badly infected bats is that they might arouse every seven to 10 days,” Lorch said.

This increased arousal frequency has dire consequences for the bats’ tiny bodies, as they burn up precious fat each time they come out of hibernation to reach their typical body temperature.

“Imagine if you’re waking up three times more often than you should be,” Lorch said. “You’re burning through at least three times the fat. And most bats don’t go into hibernation with three times the amount of fat that they need to make it to spring.”

Why exactly the infection causes bats to come out of hibernation more frequently remains uncertain, though it seems to have something to do with the P. destructans‘ propensity for disrupting bats’ bodily systems. The effect, in Wisconsin and everywhere else the fungus has been found in North America, is the near extermination of healthy cave-dwelling bat populations.

The impact on Wisconsin’s bat species

Half of the bats historically native to Wisconsin are species that migrate south for the winter. Because they don’t hibernate in fungus-infested caves, white-nose syndrome hasn’t struck those populations.

On the other hand, the state DNR has recorded steep population declines in most of Wisconsin’s hibernating bats. By 2018, bat populations at the first known infection site in Grant County were reduced from a historic average of around 1,000 to just nine individuals, according to the DNR. Hibernacula known to be infected the following year saw declines nearly as severe.

Additionally, annual summer bat counts of little brown bats in Wisconsin have shown significant declines since 2016. Tri-colored bats, also known as eastern pipistrelle bats, have also declined rapidly, according to the DNR.

But it’s the decline of another species that has scientists like Lorch increasingly uttering the word “extinction.” The northern long-eared bat has been by far the most heavily afflicted species in Wisconsin.

“It’s my understanding that the species looks like it’s on its way to disappearing from the state,” Jeff Lorch said. Such an event, where a species disappears from a specific region but persists elsewhere, is known as “extirpation.”

But northern long-eared bats could very well disappear entirely from the landscape in the coming years, he added, and not just in Wisconsin.

On the other hand, there do seem to be surviving populations of little brown bats and other impacted species in the state. These include populations of little brown bats surviving in hibernacula along the Mississippi and Wisconsin rivers, according to Heather Kaarakka, a conservation biologist at the DNR.

“There seem to be concentrations of bats there where the colonies seem to be holding on a little bit better than in other parts of the state,” Kaarakka said. “We’re not entirely sure why that is.”

But even if a small number of little brown bats or other species persist, Lorch said their reduced numbers will make them much more vulnerable to other potential threats. Bats’ reproductive systems don’t help the matter either: Most species typically give birth to just one pup per year, and survivability to adulthood is very low, he said.

“People think of bats as mice with wings, and we think of mice as having these really high reproductive rates,” Lorch said. “But that’s really not the case for bats. They’re very slow reproducing species. But, these bats in the wild can live, I think the record is, somewhere around 40 years. So they really have a reproductive strategy that depends on them living a long time to replace themselves.”

White-nose syndrome is short-circuiting that strategy, making even little brown bats vulnerable to extinction in the long-term.

Meanwhile, big browns are the least affected of Wisconsin’s hibernating bat species. This is likely partially due to big browns’ propensity for hibernating in buildings in addition to caves and old mine shafts.

“They might just not be as exposed to the fungus as some of the more vulnerable species,” Lorch said.

The uncertainty that continues to swirl around white-nose syndrome and what makes certain species or populations more susceptible to it is a vexing challenge for scientists like Lorch and Kaarakka, who are racing against the clock to protect the bats’ long-term survival.

Lorch and other microbiologists are currently investigating the microbial environments living on bats’ bodies and around their hibernacula to see if as yet unidentified processes may provide protection against or reinforce the effects of P. destructans. Other researchers in Wisconsin are also working on a potential vaccine, though developing fungal vaccines is very difficult and deploying one in the wild is logistically challenging.

Breakthroughs or not, white-nose syndrome is in North America to stay, Lorch said. He noted that the conservation community is particularly worried about the disease’s spread west, where there are many more species that could become vulnerable.

In Lorch’s mind, the disease already ranks among the worst ever known to affect wildlife. “The declines we’re seeing in bats are unprecedented for any sort of mammal decline,” he said.

Along with a notorious fungus responsible for wiping out amphibians around the world, Lorch said, white-nose syndrome is “the most devastating wildlife disease we’ve had in recorded history.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us