American Experience producer Sharon Grimberg discusses “The Circus”

September 24, 2018 Leave a Comment

Step right up! American Experience: The Circus is a four-hour, two-part documentary airing 8 p.m. Monday and Tuesday, Oct. 8-9 on WPT. Exploring the colorful history of this distinctly American entertainment, this fascinating film includes extensive historical material from and about Wisconsin, the home of the famed Ringling Bros. and other major acts.

Step right up! American Experience: The Circus is a four-hour, two-part documentary airing 8 p.m. Monday and Tuesday, Oct. 8-9 on WPT. Exploring the colorful history of this distinctly American entertainment, this fascinating film includes extensive historical material from and about Wisconsin, the home of the famed Ringling Bros. and other major acts.

In our exclusive Q&A, writer/producer/director Sharon Grimberg shares her thoughts on the film’s production, as well as the circus itself.

Sharon Grimberg has more than 20 years of experience working for public television. As senior producer of American Experience for more than a decade, she played a key role in the origination, development, acquisition and editorial oversight of more than 130 films, including as executive producer of The Abolitionists, which was nominated for a Primetime Emmy and a Writers Guild Award.

WPT: Before you started this film, what were your strongest memories or associations with the circus?

GRIMBERG: Like many Americans, I’m an immigrant. I grew up in Singapore, and I honestly don’t remember circuses coming to Singapore when I was a child.

I do have a very fond memory of my son’s first experience at the circus. He was about four years old and I had bought tickets to a small youth circus. He didn’t want to go; I had to drag him out of the house. But he was mesmerized by it all: the music, the clowns, the stunts. He loved it so much he wanted to stay all day. I remember being struck by how much the circus spoke to him.

American Experience executive producer Mark Samels has said, “There’s so much of American history that we don’t know.” What didn’t you know here, and what did you want to find out?

One of the things that I came to fully appreciate by studying the history of the circus is how disconnected Americans were from each other before a national press, before radio. Many Americans were immigrants. They didn’t speak English well; they had different cultural traditions. The circus was something that united them. Someone in Ohio could see the same circus as someone in Georgia or in New York. The circus helped create a common American culture.

I found it particularly fascinating, for instance, to learn that many Americans first heard ragtime and jazz at the circus. That’s because, starting in the late 19th century, many circuses employed a black sideshow band. African Americans were rarely allowed to perform under the big top. They were confined to the sideshow where the so-called “freaks” performed. Under the leadership of some very talented black band leaders, these musicians started to play jazz and ragtime.

This was before radio, before the Harlem Renaissance. The circus brought African American music around the country to people who would never have sought it out, but who loved it nonetheless.

How did you prepare for this film?

At first, I found the story somewhat daunting – so many potential characters, so many amazing and unexpected stories. Ultimately, there is a rise and fall story of the circus itself.

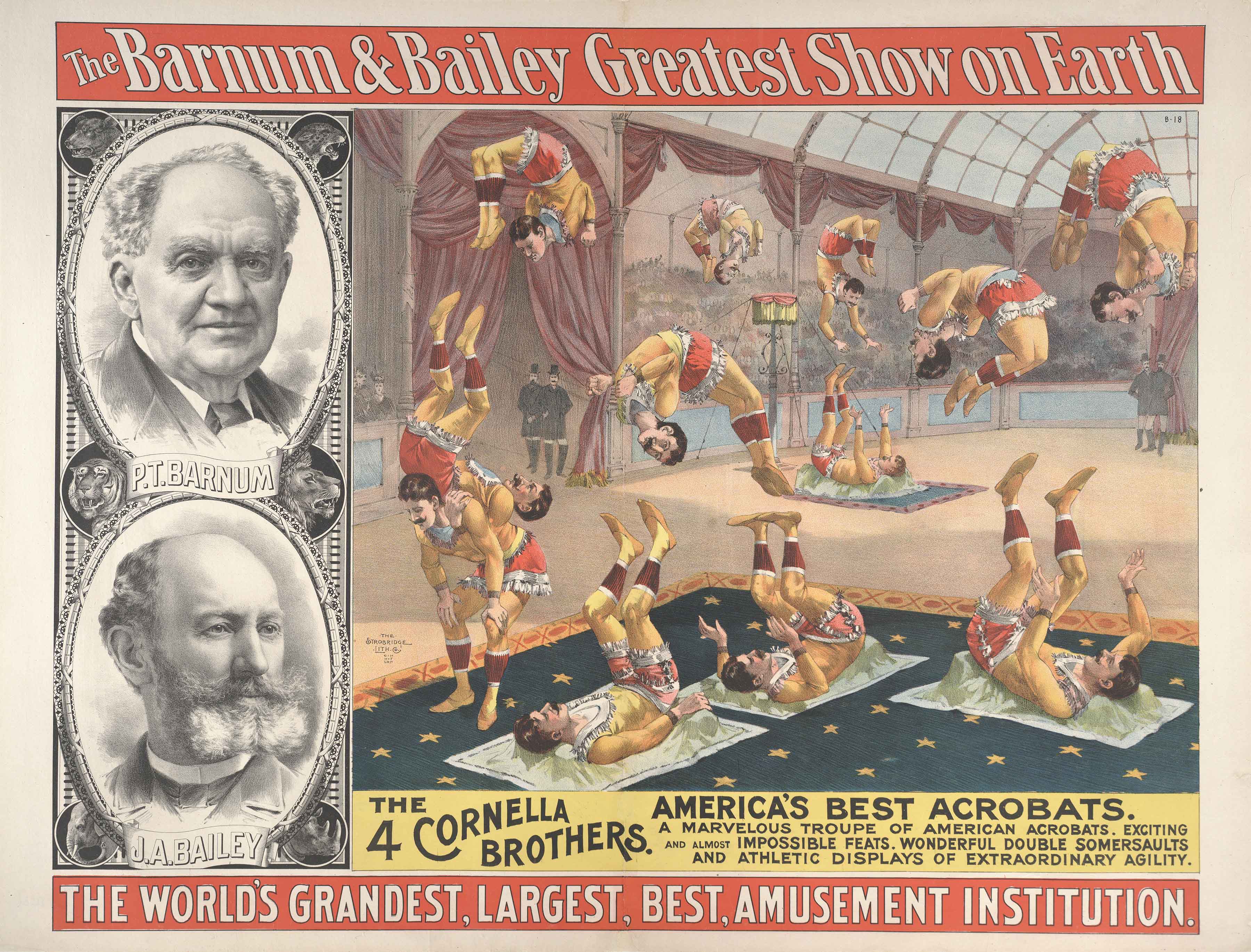

The circus came to America from England in the late 18th century, when America was a cultural backwater. Over the next century, the circus became a massive, spectacular, itinerant entertainment – made possible by American ingenuity and technological development. Whereas European circuses were small, intimate affairs that often played in permanent circus buildings, the American circus was massive and was run like an industrial enterprise. By the late 19th century, the largest circuses employed some 1,000 people and traveled on more than 80 railway cars. They traveled night after night, putting on shows in cities that could be 100 miles apart.

Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus train in Safety Harbor, Florida, 1992. Photo: James G. Howes (via Wikimedia Commons)

In fact, when James Bailey took the Barnum & Bailey Circus to Europe for five years, the Prussian military was fascinated. How did the circus mobilize so many people, feed them, put up a dozen or more tents, mount two shows and a parade and then travel overnight to the next location? They followed the circus to understand how it was done.

There is also an unraveling of the story.

At one point in American history, Circus Day was one of the most important days of the year, rivaling July 4th and Thanksgiving. Everyone went to the circus -factory workers, farmers, schoolteachers, captains of industry. The writer E. B. White loved the circus. The poet Emily Dickinson was moved by the circus. But by the 1910s, with radio, and cinema and later with television, the circus ceased to be central to the American experience. It became an increasing struggle to bring in the audiences.

Anything you wish had made it into the film?

There were many really wonderful insights from circus people about life with the circus in the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s. We could only include so many.

One of my favorite anecdotes came from writer Edward Hoagland, who was a cage boy looking after the big cats for two summers while he was an undergraduate at Harvard. He remembers spending the first night after he joined the circus in the baby orangutan’s cage. He did that because he didn’t want to be robbed by local thugs. Often there were fights between locals and circus people and he wanted to be safe. Later on, he used to sleep under the lion’s cage because the bars of the lion’s cage were wide enough that the lions could hang their paws out and he said those paws were very good protection.

How did you approach the topic of animals in captivity?

This film is a history. Central to the narrative is this question: Why did all kinds of Americans – African American, white, new immigrants, factory workers, farm hands, intellectuals and industrialists – go to the circus?

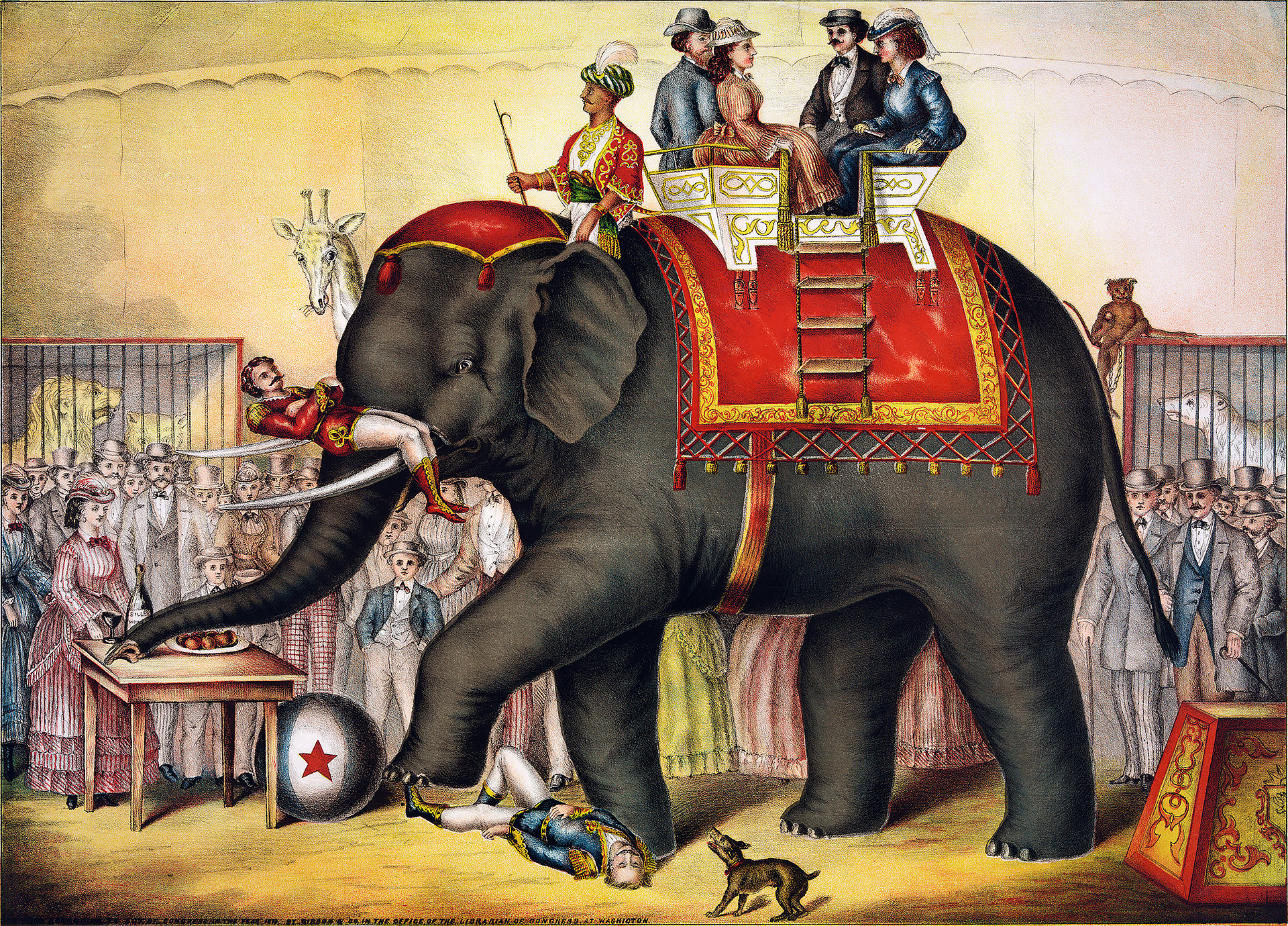

Part of the answer could be found in the animal menagerie. Most large circuses had a menagerie or small zoo of non-performing animals. For many Americans, seeing elephants or tigers or camels was a wondrous and elevating experience. Most American towns didn’t have zoos until the early 20th century. The circus was really the only place many Americans would ever see any of these animals. Consequently, shows made much of the diversity and size of their menageries in their advertising.

Part of the answer could be found in the animal menagerie. Most large circuses had a menagerie or small zoo of non-performing animals. For many Americans, seeing elephants or tigers or camels was a wondrous and elevating experience. Most American towns didn’t have zoos until the early 20th century. The circus was really the only place many Americans would ever see any of these animals. Consequently, shows made much of the diversity and size of their menageries in their advertising.

As we point out in the film, most Americans didn’t think about how the animals got there, and they weren’t really concerned with how they were treated or whether it was or wasn’t cruel. Americans were accustomed to using animals for labor and there wasn’t a very large or active animal rights movement until later in the 20th century. As a result, we don’t delve into issues surrounding the use of performing animals in the circus in the same way that a film about the contemporary circus probably would.

Anything you’d add about Wisconsin?

Wisconsin’s own Fred Dahlinger, author of Badger State Showmen, has a lot more on this. Dozens of circuses made Wisconsin home at one point or another in the 19th century, including a successful outfit run by the Gollmar Brothers.

But most famous of them all, of course, were the Gollmars’ cousins, the Ringlings. The five Ringlings based their circus out of Baraboo for more than 30 years. Al. Ringling, the eldest of the brothers, always felt Baraboo was his home and he did build a beautiful movie theater for his hometown, which of course stands and operates to this day.

Baraboo is also home to Circus World Museum, which is an incredible resource for researchers and a great destination for tourists. The archives house hundreds of thousands of photos, posters, pamphlets and route books, as well as hundreds of reels of film. It’s a real treasure trove. We literally couldn’t have made this film without them.

Did you have a favorite “nugget” you uncovered while making this film?

One of my favorite discoveries is that the women of the Barnum & Bailey circus were active in the pro-suffrage movement.

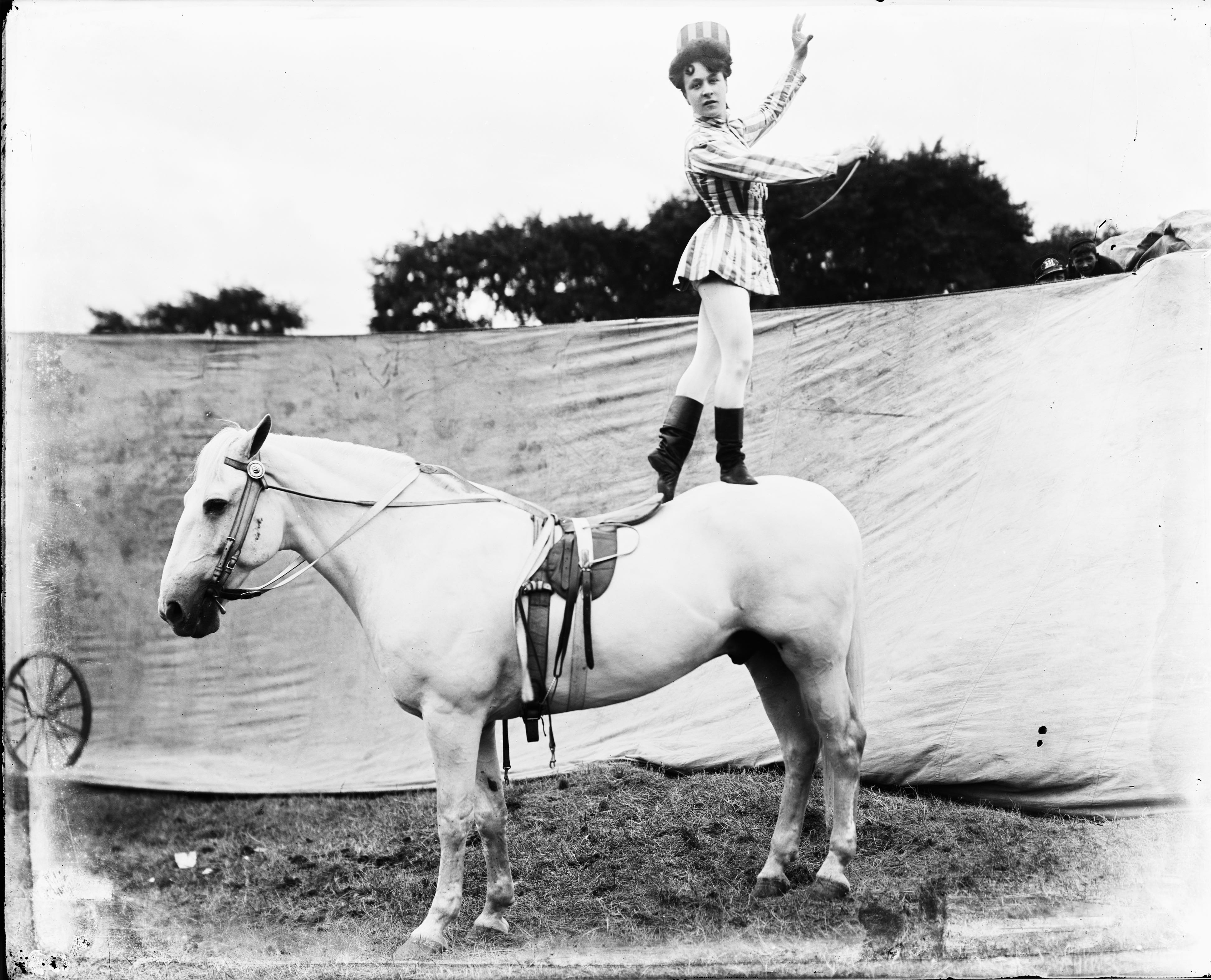

Josie DeMott, an accomplished equestrian, headed the circus’s first Votes for Women meeting in 1912. She did so in Madison Square Garden, where the circus was showing that spring. The women gathered in the menagerie room, and Josie DeMott told them – in front of members of the press – that they earned a living and should have a say in the running of the government.

The women of the circus then went to meet some of the leaders of the suffrage movement to ask how they could spread the women’s suffrage message. The suffrage leaders told the circus women that by just doing their jobs they demonstrated that women should have the right to vote. They proved every day that women had the courage and endurance of men.

I love that story. It shows how inspiring circus performers were to other women – and, also, how fiercely independent circus women were.

When and why did the circus experience start to decline?

The circus was at the height of its influence and power at the beginning of the 20th century. But in a few short years, that cultural dominance began to diminish. Initially, new kinds of competing entertainments were a large part of the problem. Many cities began to have zoos. There were nickelodeons and then movie theaters. By the mid 1920s, many Americans had radios in their homes.

The Great Depression, of course, took its toll on all kinds of entertainment. After World War II, other factors conspired to make it unprofitable to run a large circus that traveled by train. Railroad freight rates shot up, for example, so moving the circus train in 1952 cost three times as much as it had in 1935. Plus, logistically, it got harder to operate mammoth circuses in the way that they had operated. For instance, in 1951, the Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey Circus travelled with 41 tents: there were tents for the horses, for dressing rooms, etc., as well as for the performances. The circus needed 15 acres to put up all those tents. So as urban sprawl became endemic across America, circuses had to go further and further away from city centers, way out beyond the suburbs, to find lots large enough.

But the big kicker, of course, was television. By 1955, half of American households had a television. You could see circus acts on television, on The Ed Sullivan Show. You didn’t need to traipse out to the suburbs. Plus, it didn’t cost you anything.

Finally, what’s your personal position on clowns: fun, scary or something else?

I am not someone who finds clowns particularly scary! Perhaps that’s because I’m not a horror movie fan.

I’d love to go back in time and see some of the early circus clowns. In the 19th century, the most famous clown was a man named Dan Rice. Before the Civil War, when circus tents were smaller, clowns used to talk, and Dan Rice was one of the most famous men in the country, renowned for his political satire.

I’d love to go back in time and see some of the early circus clowns. In the 19th century, the most famous clown was a man named Dan Rice. Before the Civil War, when circus tents were smaller, clowns used to talk, and Dan Rice was one of the most famous men in the country, renowned for his political satire.

Frank “Slivers” Oakley was also a remarkable and much beloved clown who performed at the beginning of the 20th century. In his most famous skit, he acted out a baseball game playing the role of every single player as well as the umpire. Apparently, it was completely hilarious. Of course, Oakley would become supplanted by silent movie stars like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, who owed him a huge debt. They brought his style of humor to the big screen.

Photo credits: Circus tent entrance used with permission from Illinois State University’s Special Collections, Milner Library. Sharon Grimberg: Rahoul Ghose/PBS. Aerialist, equestrienne, group of clowns and Barnum & Bailey acrobat poster courtesy of Collection of The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, the State Art Museum of Florida, Florida State University

interview American Experience American Experience: The Circus The Circus

Passport

Passport

John Anthony Marrone says:

I ran away with the Circus in 1975. It has been good to me for 44 years. Thank you for this great documentary. It was quite accurate and picked up some subtle fine points too. From my perspective, you missed a few subtle points also.