A birthing center in Waupaca closes in the wake of a health system merger

After decades of delivering babies in Waupaca, ThedaCare-Froedtert Health shuttered its OB-GYN unit there in February, reducing local health care options and increasing the need for travel in the small, rural Wisconsin community.

The Badger Project

March 17, 2025 • Northeast Region

ThedaCare, a health care system that operates medical facilities in northeastern Wisconsin, closed the birthing center at its facility in Waupaca in February 2025. (Credit: Courtesy of Russell Butkiewicz via The Badger Project)

Since 1954, women in Waupaca and the surrounding areas could give birth at the local hospital.

No longer.

In 2024, the health care system ThedaCare that runs the hospital merged with another system, Froedtert Health. In February 2025, that newly-formed health care system closed the delivery unit there.

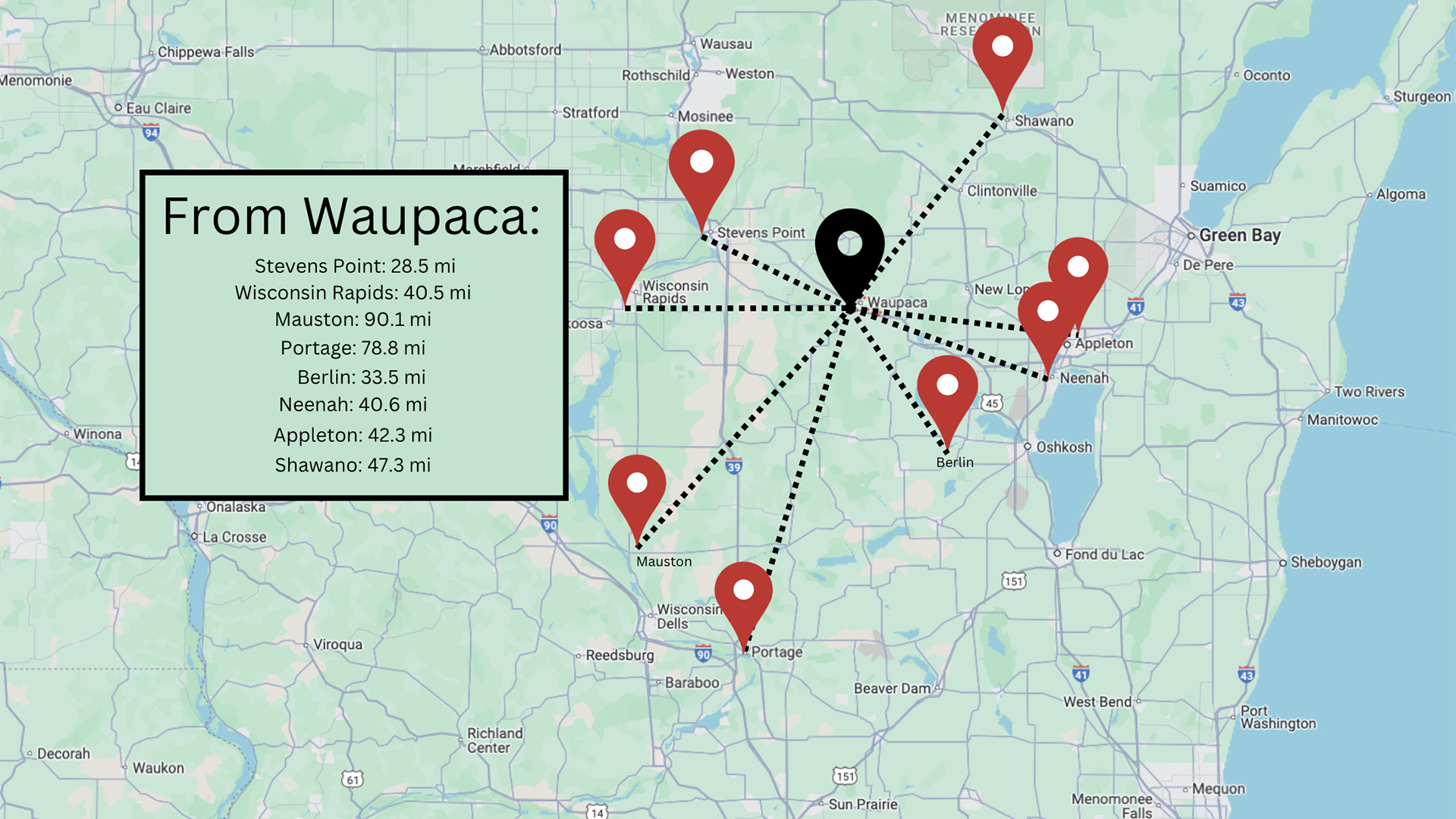

The closest birthing center to Waupaca is now more than 30 miles to the northwest in Stevens Point. But many pregnant women will have to go even farther — to the Fox Valley to the east — to reach a hospital that accepts their insurance, said Dr. Russell Butkiewicz, who worked as a family physician at the Waupaca hospital for more than 30 years, including over a decade of delivering babies in the now-closed birthing center, before retiring from medicine last year.

“There’s going to be a delay in care,” he said. “And that delay in care could result in an adverse outcome. It could mean harm to the mother. It could mean harm to the fetus.”

Closures are common after mergers, and a particularly sticky problem in more rural communities, which have fewer people and thus make less financial sense for profit-driven organizations, said Peter Carstensen, a professor emeritus in the UW-Madison Law School who focuses on competition policy. When competitors merge, they look for areas to reduce cost.

“It almost always means eliminating some overlapping activities,” he said.

In Waupaca, that means goodbye to the delivery unit. And that’s a problem for folks in the area. One that has repeated itself across the state and country.

With the closure of the ThedaCare delivery center in Waupaca, pregnant patients near that community will need to travel to other facilities in surrounding areas for care. (Credit: Sammy Garrity / The Badger Project via Google Maps)

The community tried to offer solutions to the health care system and keep the birthing center open, Butkiewicz said. The Waupaca City Council asked the health care system in December to reconsider the closure.

The health care system told the press it was struggling to recruit physicians and other specialists for the unit, and said that most women in Waupaca were already delivering their babies in urban hospitals. But they also did not show data to back up those assertions, according to news reports.

The health care system did not respond to messages from The Badger Project seeking comment.

The past and the future

For more than 70 years, the community’s babies were born at the hospital in Waupaca. ThedaCare took control of the hospital in 2006, but kept on delivering — until the merger.

While the newly-formed health care system is technically nonprofit, it is still driven by making money, Carstensen said. High-level employees must still be compensated competitively by nonprofit organizations.

“They’re really run in the interest of the executives and doctors, who are the managers, the owners of the not-for-profit,” he continued. “The goal is to increase your profits and lower your costs.”

Butkiewicz and others worry the ThedaCare delivery unit in Waupaca won’t be the only casualty of the merger.

They also fear the closing of the birthing center at the ThedaCare medical center in nearby small-town Berlin, with its relative proximity to larger hospitals in Oshkosh and Fond du Lac, could be next.

A closure there would again increase the size of the territory in central Wisconsin without a birthing center, Butkiewicz noted, further extending drive times and escalating the dangers of problematic deliveries.

The health care system did not respond to questions about Berlin or anything else.

Signs mark the now closed delivery ward at the ThedaCare Medical Center in Waupaca, which was shuttered in February 2025. (Credit: Courtesy of Jane Peterson via The Badger Project)

The problem of profit-centered health care, the dominant model in the U.S., not wanting to serve less-profitable areas is a consistent problem, solutions do exist.

When the free market does not fill a need, the government can step in to help, Carstensen said.

That can take the form of direct payments to a health care system to help provide the needed care, or a government promise that the organization will have a monopoly in the area as long as they offer certain services to the public.

Something similar is happening in the state regarding high-speed internet. Across rural Wisconsin and also much of the rural United States, for-profit telecommunications providers mostly have been uninterested in making the necessary investments to bring fast internet access to the thinly-populated customers here. Republicans controlling Wisconsin state government initially gave very little funding toward the problem. But after Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat, was elected in 2018, he and the GOP-controlled state Legislature massively increased the amount of grants for internet providers to rural areas in the state.

The idea of government stepping in to subsidize the free market is generally one more appealing to Democrats than the GOP.

State Sen. Rachael Cabral-Guevara, a Republican from Appleton who represents Waupaca and also runs her own health care practice as a nurse practitioner, has some other ideas for helping health care thrive, or at least survive, in rural areas.

“Patients deserve access, but first we need to make sure providers — particularly in high-demand areas like nursing — are incentivized to provide these critical services in needed areas,” she said via email. “This includes cutting unneeded red tape in the health care industry, especially for primary care providers.”

To specifically tackle this shortage of health care providers, particularly in rural areas, she argued for allowing them more independence to offer more services, enhancing investments in nursing student recruitment and retention, and supporting a tax credit for nurse educators.

State Rep. Kevin Petersen, a Republican who also represents the area, did not respond to messages seeking solutions.

Whatever happens, rural health care will need some help from somewhere, or much of it might go away, experts say.

“It’s going to involve a lot more regulatory oversight,” Carstensen said. “It’s the only way we’re going to get the results I think are essential.”

Former President Joe Biden’s administration had been very aggressive on business competition issues for the past four years, including challenging many attempts by large companies and nonprofits to merge, often arguing the results would be worse for consumers. It remains to be seen how strongly President Donald Trump’s administration will enforce antitrust law in his second term, though early moves have been promising, Carstenen noted.

The Badger Project is a nonpartisan, citizen-supported journalism nonprofit in Wisconsin.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us