Opioid Scourge Has Spread, Not Shifted, Across Racial Groups

As opioids increasingly dominate the national conversation about substance abuse, addiction and overdose deaths, public health professionals are asking some difficult questions.

October 24, 2016

Opioid hydrocodone pills in a plastic bottle

As opioids increasingly dominate the national conversation about substance abuse, addiction and overdose deaths, public health professionals are asking some difficult questions.

One, why didn’t observers in the field see this trend emerging sooner, as more and more people overdosed on prescription opioids and started using heroin, which is at historically cheap prices?

Two, did the opioid epidemic become such a public health policy priority in part because it increasingly affects people from white, middle-class backgrounds?

In Wisconsin, legislators’ bipartisan Heroin, Opiate, Prevention, and Education (HOPE) Agenda has taken a compassionate approach to opioid users, emphasizing treatment policies like rehabilitation and increasing access to the overdose remedy Narcan over expanding law enforcement interdiction resources and criminal penalties. This direction in the state parallels a national shift in attitudes about heroin, opioids and how to address their abuse.

Observers have attributed policymakers’ public-health approach towards heroin to shifts in racial demographics among people who use opioids. One study published in 2014 found that almost 90 percent of the people who started using heroin over the preceding decade were white.

“Our data show that the demographic composition of heroin users entering treatment has shifted over the last 50 years such that heroin use has changed from an inner-city, minority-centered problem to one that has a more widespread geographical distribution, involving primarily white men and women in their late 20s living outside of large urban areas,” the study’s authors concluded.

However, that doesn’t mean opioids or substance-abuse problems have gotten any easier for poor, urban, and/or minority communities (which are not synonymous).

“There’s no evidence that inner-city drug abuse has dropped off at all,” said Theodore Cicero, one of the study’s authors and a professor of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis. “Our preliminary answer would be, it’s just spreading. It’s not dissipating in one area and increasing in another.”

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data indicate that African Americans suffer drug-related deaths at a higher rate than whites in Wisconsin, though in much lower raw numbers, given the state is about 87 percent white. In the years of the opioid surge, though, this gap has at times narrowed dramatically. In 1999, there were about 3.9 drug-related deaths per 100,000 people among white Wisconsinites. That number rose to 15.3 by 2013. Still, throughout this entire period, the drug-related rate has been higher for African Americans.

Racial public-health disparities can be hard to specify when there’s such a small sample size for a given demographic group, but long-term trends are still meaningful.

The crisis Wisconsin officials are now confronting with a public-health approach has been building for well over a decade. It also is evolving quickly and unpredictably. A few years ago, the biggest shift was from abuse of prescription opioids to heroin, but more recently it’s the rapid introduction of synthetic and highly potent fentanyl, often mixed in with heroin and sold to unsuspecting users. And to judge from some of the demographic data, Wisconsinites really are in this together.

Milwaukee study uncovers unexpected nuances

In Milwaukee County — an area that suffers some of the worst racial disparities in the nation — drug deaths are eerily representative of the overall population. White people accounted for 67 percent of overdose deaths between January 2011 and July 2016, according to an analysis of county death data by the Medical College of Wisconsin. White people are 64.8 percent of the county’s population, according to U.S. Census data from 2014. African Americans accounted for 25 percent of the overdose deaths.Per the 2014 population figures, African Americans are 28.3 percent of the county’s population. Of course, the city of Milwaukee has a significantly higher proportion of black people and a lower proportion of white people than Milwaukee County, indicating there is still a concentration of opioid deaths in the county’s more dense urban areas. The one racial demographic group that doesn’t match with population proportions is Hispanic people, who they account for 6 percent of overdose deaths but 13.8 percent of the population.

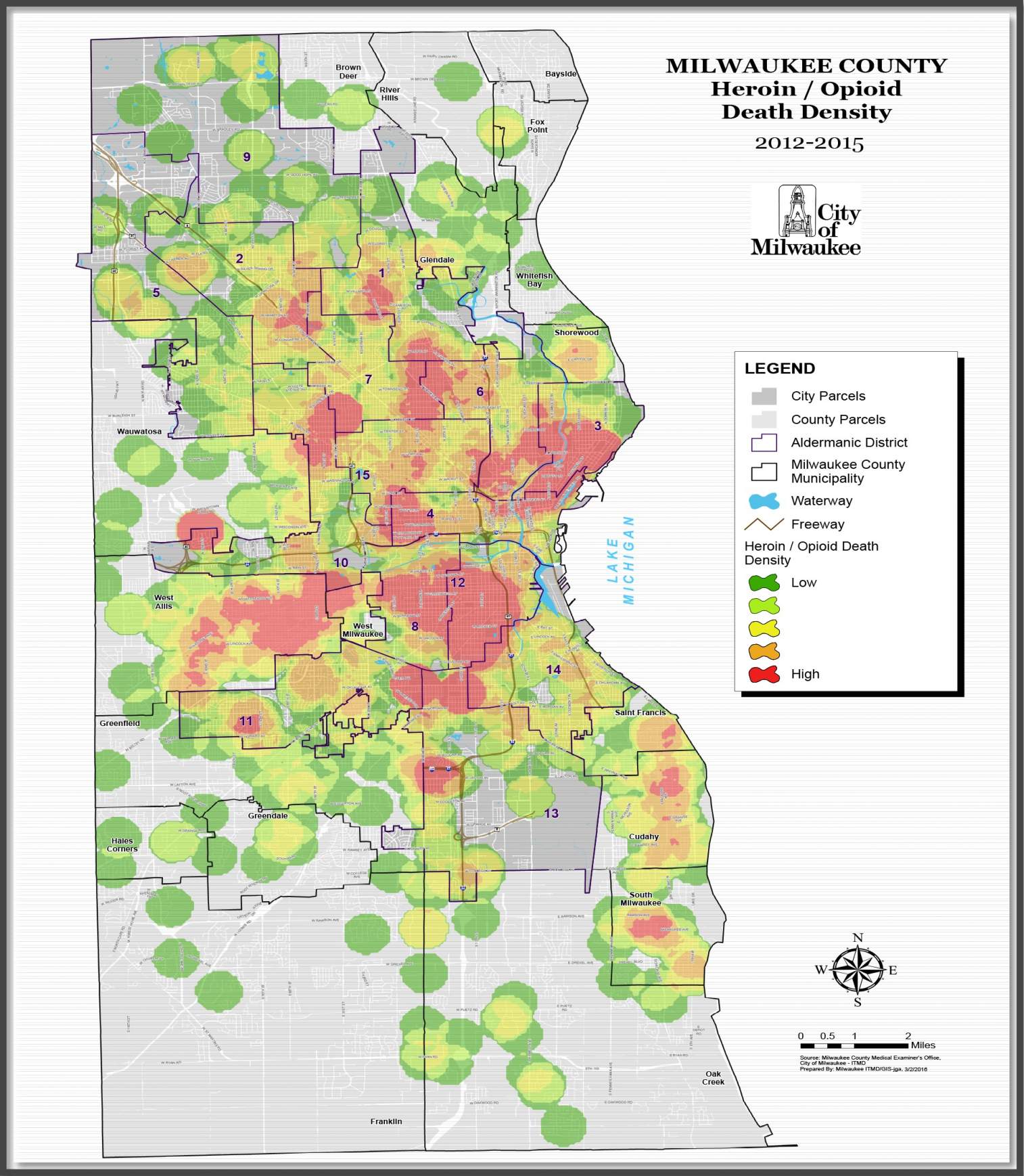

Released in early 2016, the report “888* Bodies And Counting” — part of a research project commissioned by a city of Milwaukee alderman, Michael Murphy, but covering the entire county — analyzed data from the county medical examiner’s office on drug overdose deaths from 2012 to 2015. A map analyzing the density of opioid deaths across the county showed hotspots in some of the high-poverty areas in the city, but also significant concentrations of deaths in places like West Allis, which is about 87 percent white and has a poverty rate lower than that of the country as a whole.

Both Murphy and Brooke Lerner, a Medical College of Wisconsin professor of emergency medicine taking part in the research project Murphy organized, said one of the biggest surprises in the “888 Bodies*” report is the age dynamic in overdose deaths. The initial report found that the average age of an overdose victim in Milwaukee County is 43. But there’s a divergence for different racial groups: African-American overdose victims are more likely to die during their 50s, while white overdose victims skew more toward their 30s.

As the research project continues, it has identified 138 overdose deaths in Milwaukee County just in the first seven months of 2016.

“Assuming the rate stays the same, would put us at 276 for the year, which is another rise over 2014 and 2015,” Lerner said. “We can show that basically the epidemic is here and still growing and we have a lot of work to do.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us