Wisconsin's Pioneering War Correspondent: Dickey Chapelle

Dickey Chapelle had a complex relationship with war and with her profession as a photojournalist.

September 11, 2017

Crop of Dickey Chapelle on Milwaukee beach for "Operation Inland Seas" in 1959

Dickey Chapelle had a complex relationship with war and with her profession as a photojournalist. Born Georgette Meyer in Milwaukee in 1919, Chapelle turned a thirst for adventure into a career as a war correspondent, across three decades rife with conflicts large and small around the globe, and at a time when journalism was completely dominated by men.

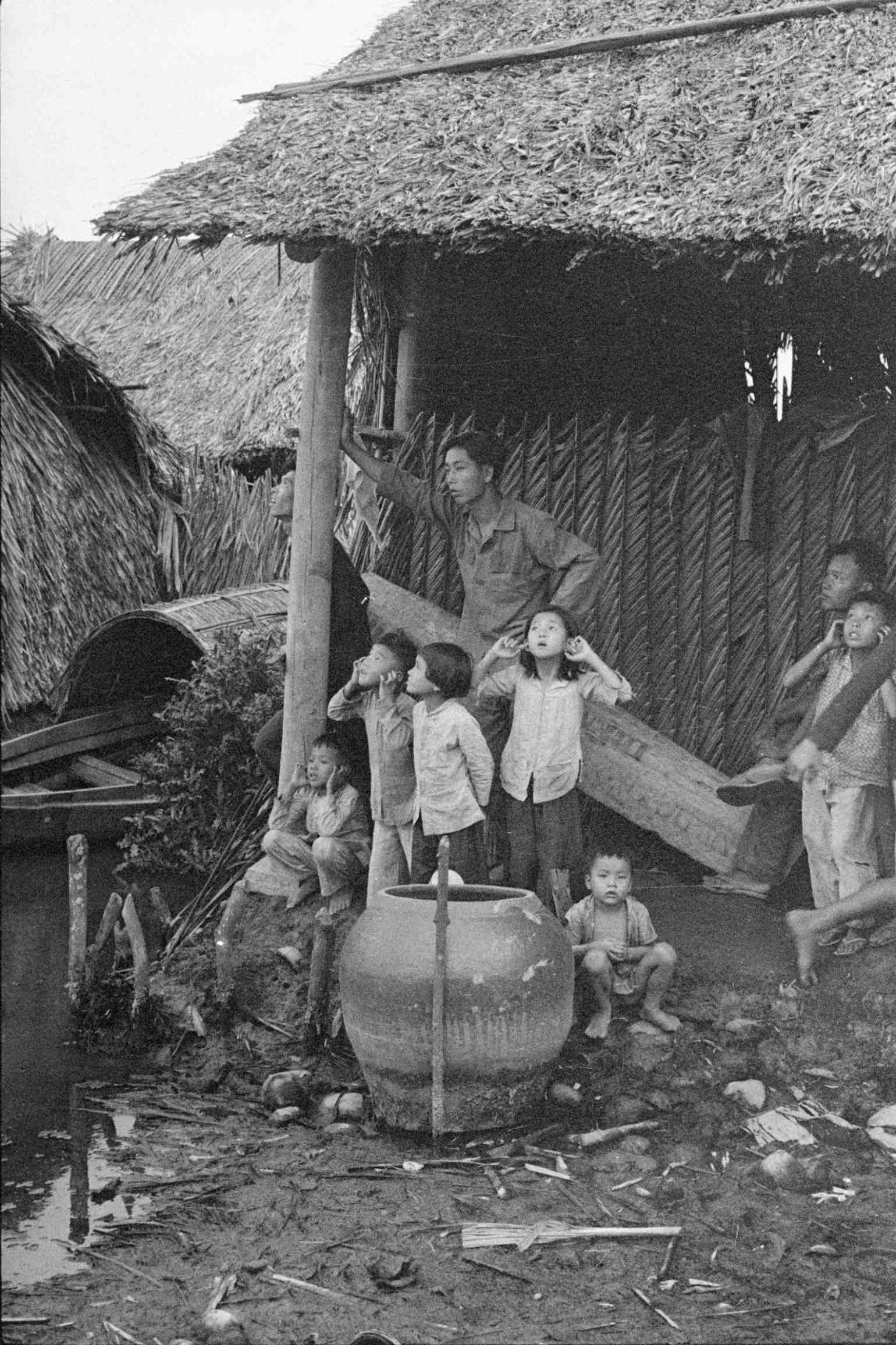

Chapelle’s dedication to capturing vivid images and stories drove her toward danger time and again. Her bravery earned her the respect of military personnel who encountered her, and her risk-taking and occasional circumvention of protocol rubbed a fair amount of high-ranking officials the wrong way. She covered U.S. military involvement in Vietnam well before it escalated into a grueling and unpopular war, and it was in Vietnam that she became the first female American war correspondent killed in action.

Emphasizing Chapelle’s gender, of course, is reductive — she was an outstanding photographer and reporter by any measure. That said, from early on in life Chapelle found herself at odds with what was traditionally expected of girls and women, and often encountered military officials who balked at the presence of a woman in the field.

Women journalists still encounter a great deal of sexism, stalking and harassment, online and in-person. Female war correspondents in particular continue to face dangers of abuse and sexual assault in the field. Some hesitate to speak up about their experiences, because doing so is traumatic and because their experiences could be used by people looking for excuses to keep women out of this important role. On top of all the other challenges and deprivations of the profession, working as a female war correspondent was an uphill battle in Chapelle’s time, and it’s an uphill battle now.

Recent years have seen a renewed interest in Chapelle’s legacy, with the publication of Dickey Chapelle Under Fire: Photographs By The First American Female War Correspondent Killed In Action by John Garofolo, and the release of the Milwaukee PBS-produced documentary Behind The Pearl Earrings: The Story of Dickey Chapelle, Combat Photojournalist. That legacy is as complex as Chapelle herself, but the most important aspect is the sense of purpose she brought to the work.

“She wasn’t just taking pictures for the sake of taking pictures,” said Garofolo in an October 24, 2015 presentation at the Wisconsin Book Festival in Madison. In his talk, which was recorded for Wisconsin Public Television’s University Place, Garofolo detailed Chapelle’s upbringing in a pacifist German-immigrant household in Shorewood, her entry into the world of journalism, and her work covering battles from the Pacific theater in World War II to the Cuban Revolution to Vietnam.

Chapelle wasn’t just an impartial observer — she participated in relief work and helped out the cause of Hungarians rebelling against the Soviet Union in 1956. She wrote that she wanted her work to document “the wreckage resulting from man’s inhumanity to man.”

Key facts

- During her childhood raised in a staunchly pacifist household of German immigrants, Chapelle developed a keen interest in aviation and adventure.

- Chapelle graduated as valedictorian from Shorewood High School and in 1935 went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on a scholarship for aeronautical engineering. But she also ended up taking journalism classes at MIT. She dropped out of college after two years of classes, deciding to go to work as a journalist instead of finishing her degree.

- After MIT, Chapelle moved back to Milwaukee and took flight lessons while working at a local airfield. Her parents sent her down to live with her grandparents in Coral Gables, Florida, hoping to get her away from what they saw as the wrong crowd. But Miami was home to a large air show, and Chapelle got a job working for it.

- While in Miami, Chapelle talked her way into a work trip to Havana, where she ended up witnessing a fatal plane crash and writing a story about it for The New York Times. This earned her a job in New York City working in Trans World Airlines’ publicity department. At TWA, she met her future husband, photographer Tony Chapelle, who was 20 years her senior.

- After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Tony Chapelle enlisted in the Navy and became an instructor in aviation photography and was stationed in Panama. Dickey Chapelle found work as a war correspondent for Look magazine and went to Panama as well, covering the 14th Infantry Division. But after she had a flashbulb mishap while taking a photo of the Secretary of the Navy, the base commander wanted Dickey to leave. He didn’t have the authority to order her off the base, but did have Tony transferred, which prompted Dickey to move back to New York and focus more on her writing.

- In 1945, Dickey secured press credentials to cover the war again, this time in the Pacific stationed on a hospital ship called USS Samaritan. She managed to convince some Marines to take her to the front on Iwo Jima, where she drew fire from Japanese snipers. Later on Iwo Jima, Dickey took one of her most iconic photos, of a seriously wounded Marine who ended up recovering after a year in the hospital. (The photo initially ran with the caption “The dying Marine.”)

- After Iwo Jima, Dickey covered the battle of Okinawa, where she spent 10 days in the field with a medical unit in the 6th Marine Division. The Navy arrested her for being on Okinawa without proper authorization, and after being sent away she witnessed several kamikaze attacks.

- Because of the incident on Okinawa, the U.S. military denied Dickey press credentials for about 10 years. During that time, she lived in New York and became a photographer for Seventeen magazine. After the war, she also participated in relief work and worked in publicity for the International Rescue Committee.

- After divorcing Tony, Dickey managed to get military press credentials again. She covered conflicts including the Hungarian uprising of 1956, the 1958 Lebanon crisis, the Algerian Revolution and the Castro brothers’ uprising in Cuba. During her time in Hungary, Chapelle helped militias fighting Soviet forces smuggle penicillin to refugees. She was arrested as a spy and imprisoned for two months by Soviet secret police, who wanted to execute her but chose not to. (Garofolo believes that when writing about this experience, Chapelle withheld some of the worst details.) During this era, her photos were published in Reader’s Digest and Life magazine.

- Chapelle traveled to Vietnam four times. Her first trip was in 1961, very early in that conflict. An award-winning photograph she published in National Geographic in 1962 showed a Marine suited up for combat, which conflicted with the Pentagon’s narrative at the time that U.S. military personnel were present in Vietnam only as advisors. At this point Chapelle was in her 40s, and worked out intensively in order to make sure she could keep up with the troops she covered.

- Chapelle died while on patrol with Marines in Vietnam on November 4, 1965. A Marine walking in front of her set off an improvised explosive. Shrapnel from the ensuing explosion struck six Marines and Chapelle, cutting her carotid artery. (A medevac helicopter was called in, but Garofolo believes Chapelle was dead before it arrived.) The renowned war photographer Henri Huet was also on that patrol, and took a photo of Chapelle as she lay dying. Huet himself was killed in 1971 when a helicopter he was riding in was shot down by North Vietnamese anti-aircraft guns.

- After Chapelle’s death, the commandant of the Marine Corps, Gen. Wallace Greene, issued a statement praising her skill and dedication. It read in part: “It has been said by her media colleagues that she died with the men she loved. And it must also be said that respect, admiration, and devotion was mutual.”

Key quotes

- On Chapelle’s perspective on sexism: “She always felt that, well, why can’t I do something if I’m capable? What difference does it make that I’m a women make to anybody? Now, of course, in the day that she grew up it made an awful lot of difference. And you can argue that, in many respects, that hasn’t changed a whole lot.”

- On Chapelle’s aviation skills: “When she was in Milwaukee, she did take flight lessons, but she was really a terrible pilot. And even she said, ‘I nearly crashed in every single part of the field.’ And the lessons that she had gotten in exchange for her work basically went to her brother who finished them off for her, because she really was pretty dreadful. And so, thank God she didn’t continue as a pilot, because this would be a very, very short story.”

- On how Chapelle got arrested as a result of her success taking photos on Okinawa: “There’s only one problem with the getting more pictures is that eventually the Navy figured out that there was a woman on Okinawa, which, A, they didn’t want in the first place and, B, she got onto Okinawa without proper approval to do so. So, needless to say, you can imagine the admiral is kind of pissed off, to say the least, and so he essentially had her arrested.”

- On the obstacles Chapelle faced getting her photos published from the Pacific theater in World War II: “She was there on an assignment on Okinawa and Iwo Jima for Fawcett Publications … I think it was the editor for Woman’s Day, said, ‘Dickey, you should know better than this. We can’t use these photos. The wounded look too dirty.’ So, she was sort of dealt with that sort of absurdity. And how do you answer a stupid question or a stupid statement like that? And you don’t.”

- On the lengths Chapelle went to to get her stories: “Now, one of the things that she did take to over time is when she was with a formation, she liked to be on point. So, she was literally right behind the first and farthest forward person in any movement that she found herself in.”

- On the dangers women journalists face when covering wars: “Now, I also believe that some of the stories that you hear today about women war correspondents and the rough treatment that they’re getting, they’re probably not telling you everything that perhaps really had gone on because of the fact that they know that it’s going to be an opportunity for people to say, ‘Well, maybe we shouldn’t have women doing this job.’ They want to continue doing their work, and so I think that they’re less likely to tell you how bad things might have gotten. And, of course, even with that, you know that there are certain circumstances where women have been kidnapped, they have been groped, they have been sexually assaulted and raped.”

- On Chapelle’s legacy: “I think that she probably never achieved her goal of showing imagery that would be so horrible that people might, that sensible people might come to the conclusion that perhaps war was a really bad thing to do. But she leaves a legacy as a war correspondent that we see today. And I actually see that if I were to sort of try to figure out how Dickey Chapelle works today that, well, what she did was she is probably a model for a lot of modern women war correspondents.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us