Wisconsin's Dramatic Drop In Refugee Admissions In 2017

As the United States increasingly closed its doors to refugees fleeing conflict and persecution around the world, resettlement numbers across the nation and in Wisconsin dropped by about two-thirds.

January 10, 2018

Refugee countries of origin collage 2017

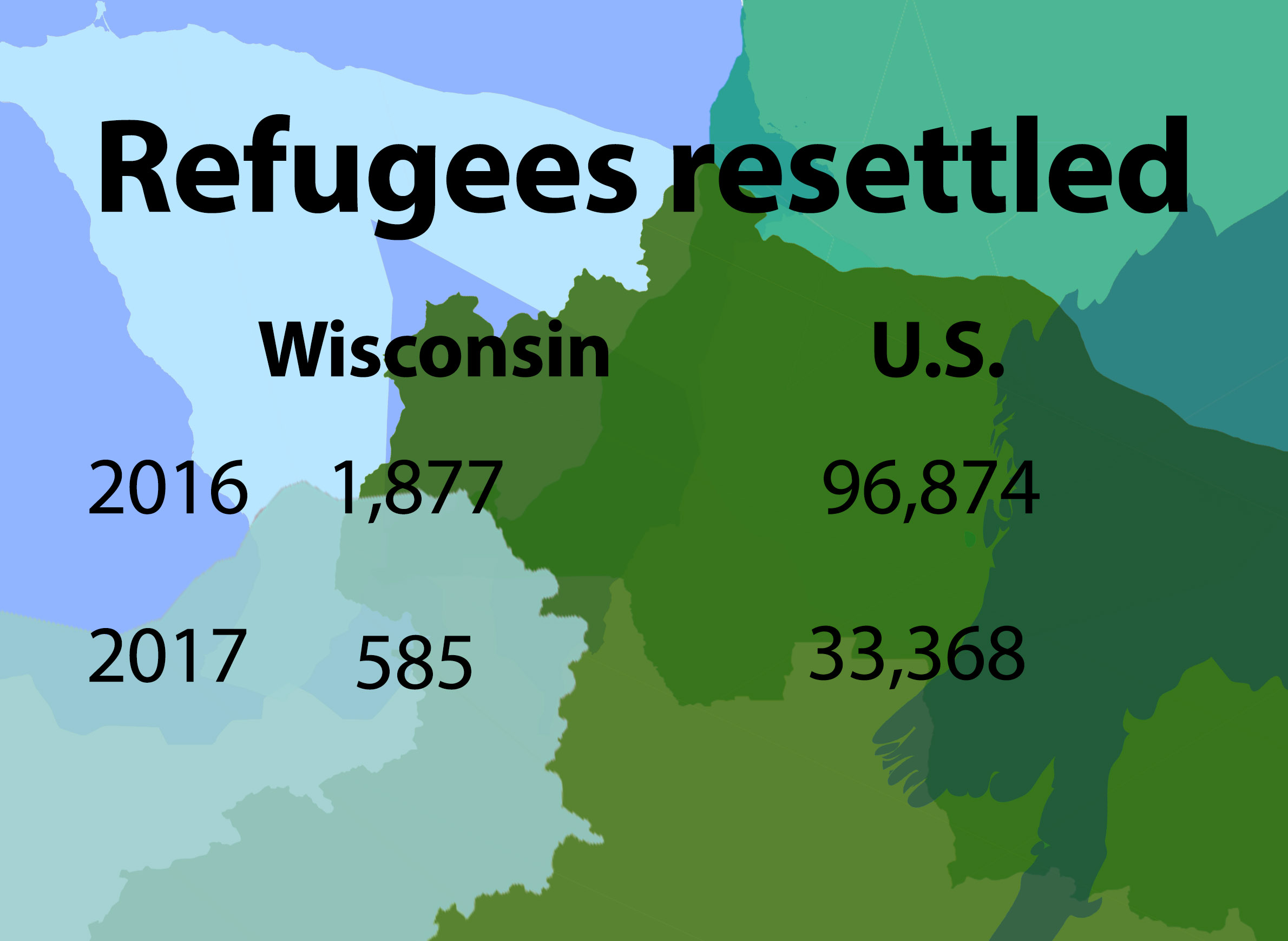

As the United States increasingly closed its doors to refugees fleeing conflict and persecution around the world, resettlement numbers across the nation and in Wisconsin dropped by about two-thirds. Between calendar years 2016 and 2017, the number of refugees resettled in the U.S. dropped by 65.6 percent. In Wisconsin, that figure fell by 68.8 percent. Refugee admission levels in the U.S. regularly have ups and downs from one year to the next, but this decrease is significant, and illustrates the power of the president to unilaterally shape the government’s refugee policy.

By sheer numbers, Wisconsin is not among the top destinations for refugees resettling in the U.S. The State Department and a network of nonprofit agencies that help refugees start new lives around the county tend to send people to where community resources, job opportunities and large immigrant populations are already in place, which generally means bigger cities and highly populated states.

But Wisconsin has a decades-long history of welcoming diverse groups of refugees all the same, including Hmong people from Laos fleeing the aftermath of the Vietnam War, a Somali community in Barron County that’s something of a rural satellite of a larger grouping in the Twin Cities, and a 21st-century influx to Milwaukee of people escaping genocide in the southeast Asian nation of Burma. Refugees in Wisconsin hail from at least three dozen countries, including Iran, Cuba, Ukraine, Liberia, Bhutan, Serbia, Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo. Since 2002, about 14,000 refugees overall have resettled in Wisconsin.

In January 2017, the Trump administration issued an executive order banning immigration, including refugee resettlement, from several Muslim-majority nations. This ban was later revised multiple times, and was in and out of effect throughout the year as legal challenges to it it worked their way through federal courts. In December, a third version went into effect after an order from the U.S. Supreme Court, even as other challenges remained active.

But whether or not the order is in force, the president has the authority to set a national goal for how many refugees to admit into the country in a given year. For fiscal year 2018, the Trump administration set that target at 45,000. In comparison, the Obama administration had set a target of 110,000 for fiscal year 2017, a level that Trump’s executive order sought to cut to 50,000.

Between Trump’s executive order and uncertainty around its status, and a surge of open xenophobia in American politics, it’s hardly surprising that the U.S. resettled fewer refugees in 2017 than it has in any other year since 2003.

Data from the State Department’s WRAPSnet database shows that 33,368 refugees resettled in the U.S. in calendar 2017, compared to 96,874 in 2016; a State Department spokesperson confirmed that the agency regards these numbers as up-to-date and accurate. For its part, Wisconsin welcomed 585 refugees in 2017 — the lowest number since 2008, and a dramatic decrease from 1,877 arrivals in 2016, and greater by percentage than the national drop.

A wrench in the resettlement process

The past year has been chaotic for the nonprofit agencies that help refugees get resettled in the state. These organizations depend in part on federal funding allocated on a per-refugee basis, so a sudden and major slowdown in arrivals can mean cutting staff or even closing offices.

Appleton-based World Relief Fox Valley kept its doors open, but laid off one staff member, director Tami McLaughlin said. However, its parent organization, World Relief, closed a handful of satellites elsewhere in the U.S. A change in this region of Wisconsin is significant in and of itself: Fox Valley cities, including Appleton and Oshkosh, are collectively the state’s second-largest destination for refugees, albeit a distant second after Milwaukee.

At one point in 2017, McLaughlin said, World Relief Fox Valley went three months between welcoming families of refugees. The organization has responded to the slowdown by focusing more on local- and state-level advocacy for refugee resettlement, and improving other services it provides for immigrants (including non-refugee immigrants) in the area.

“We’re trying to reinvent ourselves, if you will,” McLaughlin said.

Among the various kinds of immigration programs in the U.S., refugee resettlement is particularly subject to the whims of the president, said Melanie Nezer, a spokesperson for HIAS, which was formerly known as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society and is challenging the Trump administration’s refugee policies in court. The nonprofit’s local satellites in aiding the resettlement process include Jewish Social Services of Madison.

Successfully resettling an individual refugee or a refugee family depends on arranging housing and support services, making sure they have basic needs like food and furniture upon arrival, not to mention the logistics of coordinating air travel. This isn’t a process that can easily adapt to abrupt changes.

“You don’t prepare for that the day before. It takes months of preparation, finding housing,” Nezer said. “[Even] an American citizen can’t just rent a house and move in the next day. These things take time.”

What happened in 2017 was indeed abrupt, upending decades of bipartisan cooperation on refugee resettlement.

“No president after [Ronald Reagan] has ever gone after resettlement,” Nezer said. “This has always been something that presidents and members of Congress have supported.” Under the Trump administration, Nezer said, the refugee program has become a victim of politics and especially of animus toward Muslims.

Making sense of the numbers

Refugee admissions in the U.S. are inherently subject to dramatic ups and downs, because by nature they’re the result of crisis, and because other nations likewise welcome refugees, in a multi-layered, often years-long process that starts with the United Nations. Supporters of Trump’s policies have repeatedly claimed that the U.S. government doesn’t know enough about people entering the country through the refugee resettlement process, even though this process involves extensive background checks, candidate interviews, and screenings by both the U.N. and several U.S. security agencies. The entire process can take up to two years, and according to the U.N., less than one percent of the people in the world who met the definition of a refugee in 2016 were resettled in any host country.

As an example of how international issues can affect the flow of refugees, resettlement in the U.S. increased by nearly a third from 2015 to 2016, in part because of the Obama administration’s response to the crisis in Syria. That increased commitment to welcoming refugees only made the Trump administration’s reversal more consequential.

Interpreting refugee resettlement numbers is especially knotty when considering an individual state. Once the U.N. and the State Department agree that an individual refugee will be settled in the U.S., one of a handful of nonprofit resettlement agencies with local satellites works with refugees to determine which state and specific community they should move to. (State governments do not have the authority to block refugees individually or en masse, though some Republican lawmakers and governors want to change that.) Where specifically a refugee settles in the U.S. can depend on all sorts of factors, including where support resources are available, and where the refugee might have family members or find an already established community of people from their home country.

As another example of a major change in a single year, Wisconsin’s refugee admissions increased almost tenfold between 2003 and 2004, as federal officials made a large push to bring over about 15,000 Hmong refugees from a camp in Thailand, continuing a process that began at the end of the Vietnam War. In just a couple of years, more than 3,000 of those refugees — whose official country of origin was primarily Laos, though the Hmong have long been something of a stateless people — joined existing communities in Appleton and other Wisconsin cities.

Even with caveats in mind, 2017 marked a major turn in refugee resettlement in the U.S.. Since 2002, the number of refugees entering the nation as a whole has seen its share of significant ups and downs, but never a drop of quite this magnitude. Wisconsin has seen wider ups and downs relative to the small overall number of refugees it takes in, but 2017 still saw a precipitous drop, excepting those years following the 2004 spike in Hmong refugees.

One resettlement trend continuing in 2017 was that people from Burma (also called Myanmar) make up the fastest-growing group of refugees entering Wisconsin. By the numbers, refugees from Somalia were a distant second. Refugees from Syria have been very much in the public eye, and 57 did resettle in Wisconsin in 2017, but overall they’ve made up a pretty small portion of refugees entering the state. Since 2002, 181 refugees from Syria have resettled in Wisconsin, compared to 6,606 from Burma.

Only in the latter months of 2017 did crises in Burma receive significant media attention, with international scrutiny intensifying on the Burmese government’s persecution of the Rohingya, a largely Muslim ethnic minority concentrated in a western coastal region of the nation.

However, the Rohingya aren’t the only group Burma’s largely military-controlled government has persecuted. Only a small number of Burmese refugees who have resettled in the U.S. are Rohingya, Nezer said. Most are other religious or ethnic minorities, some of whom have spent years living in refugee camps in Thailand before getting a shot at resettling permanently in another country. Even members of Burma’s Buddhist ethnic majority have also fled a government that, even after some political reforms, has a strong military influence built into its governmental structure. The example of Burma reflects a common lag in the process of recognizing and resettling refugees, as officials at the U.N. will wait years before becoming convinced that victims of a given crisis simply cannot go home.

In 2017, more than half of the refugees resettling in Wisconsin were from Burma, continuing a trend that has been in place for years. Whatever direction future U.S. policy takes towards resettlement, these refugees have become an established community in the state.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us