Wisconsin's Annual Lyme Disease Forecast Is Not A Simple Matter

As the weather warms and more people head outdoors, a complex interplay of factors, some of which scientists are still trying to understand, will determine how seriously Lyme disease will afflict Wisconsin in 2018.

By Scott Gordon

May 24, 2018

Deer tick on grass leaf

Wisconsin had one of its worst Lyme disease seasons yet in 2017, according to data reported to state health officials. As the weather warms and more people head outdoors, a complex interplay of factors, some of which scientists are still trying to understand, will determine how seriously the bacterial infection will afflict the state in 2018.

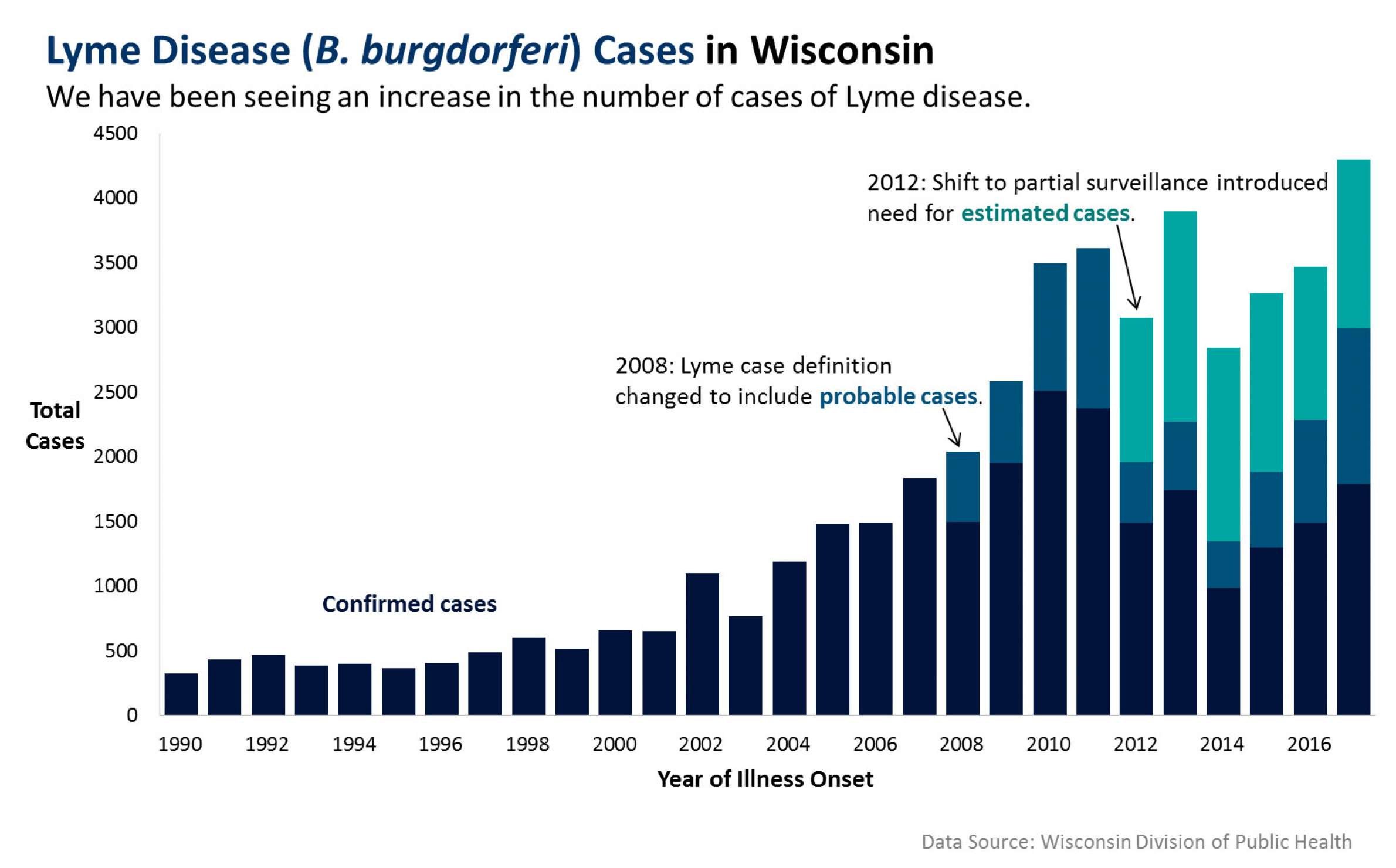

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services reported 1,788 confirmed cases in the state in 2017, compared with 1,491 in 2016. “Confirmed” cases are those verified by lab tests; public health officials also count “probable” cases based on medical diagnoses from symptoms, like the rashes that Lyme disease often causes. Since local- and state-level health agencies know that Lyme disease is underreported in Wisconsin, they also create estimates to account for cases that may have been diagnosed but not officially reported.

Forecasting the seasonal population of ticks is a slippery practice. The health of tick populations, and the likelihood of certain ticks picking up and spreading pathogenic bacteria during their life cycle, depends a great deal on weather and other wildlife. A long winter, like the one that brought Wisconsin blizzards in April 2018, could delay their emergence in the spring and summer. Ticks need heat, but don’t like extreme heat. They fare better when there’s plenty of moisture in the air — yet another reason why humid Wisconsin is a welcoming habitat. And even when ticks are doing just OK, Lyme disease can still pose a significant threat in Wisconsin.

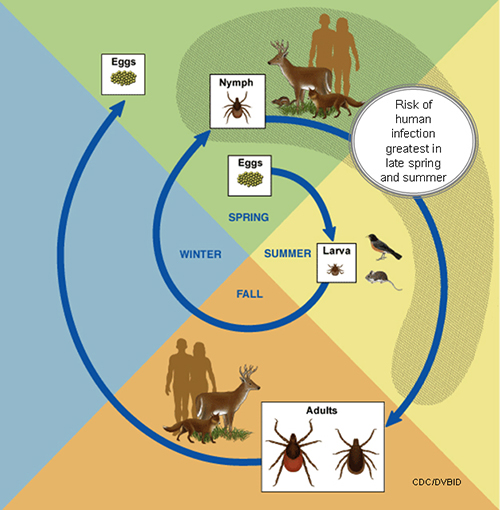

The deer tick is the species in Wisconsin responsible for transmitting the bacteria (primarily Borrelia burgdorferi) that causes Lyme disease. Also known as the black-legged tick (Ixodes scapularis), they feed on blood from mammals, birds and/or reptiles at three stages of their life cycle. While deer are a favored food source, a whole variety of small critters including mice can carry pathogens, which ticks can pick up and spread to whichever creature they feed on next. Given this role, how robust these smaller animals are, and where they congregate, affects the spread of Lyme disease and other tick-borne illnesses.

Deer ticks have a two-year life cycle, so during tick season the activity of ticks in their various life stages — larva, nymph and adult — will overlap. Nymphs that were dormant during winter will get busy earlier in the season, from May to July depending on conditions, yielding an adult-stage population that becomes more prominent in fall and winter. Newly hatched larvae will generally surge a bit later on, during August and September.

When tracking data over time, public health researchers take care not to make too much of any change between one year and the next. These trends are tracked over the course of multiple years, and a short-term change in one direction doesn’t always align with long-term trends. In terms of the difference between 2016 and 2017, though, confirmed Lyme cases in Wisconsin jumped 22 percent.

“That was an amount that was larger than we were anticipating,” said Christine Muganda, an epidemiologist with the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. It remains to be seen if this leap indicates a change from the more gradual but unmistakable increase the state has been seeing over the years for Lyme and other tick-borne diseases.

Another long-term trend, which continued in 2017, is that Lyme disease is increasingly moving south and east across the state. Northern and western Wisconsin still have the worst incidence, but the rest of the state is seeing more cases than in past years. There may be a limit to how much Lyme disease can increase its footprint in these areas, though. They’re Wisconsin’s most populous and built-up regions, which means there are more people to infect, but often less of the habitat where deer ticks can thrive.

It’s not clear why the state had more Lyme disease in 2017. More ticks? Maybe not, butmore of the ticks that were out there could have been carrying the disease-causing bacteria.

“Last year did not seem to be a boom year for tick density,” said Susan Paskewitz, a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor of entomology who conducts field research on ticks and the diseases they carry. “We didn’t see a lot more ticks like we did in 2013 … I think the infection rates were higher in those ticks, and we don’t have an explanation for why that would be.”

The prolonged winter of 2017-18 might end up thinning out the population or slowing the emergence of white-footed mice, an important reservoir of Lyme disease on which deer ticks feed. That change could affect how many Wisconsinites get Lyme disease in 2018, though Paskewitz is loath to make predictions. She also points to the importance of weather and moisture — if summer gets off to a hot, dry start, that could set tick number back.

“Usually the nymphal ticks don’t do well in that kind of weather, and that would change everything and we’d have low tick year,” Paskewitz said.

Another possibility comes down to human behavior, said Jean Tsao, a Michigan State University disease ecologist who has collaborated with Paskewitz and monitors ticks at sites around the region and nation, including Fort McCoy in Wisconsin. If more people head out for hikes in brushy tick habitat, or spend a lot of time in the woods or tall grasses around their own homes, that will increase their exposure risk. Such factors in turn interact with plenty of others, from weather to how many ticks are getting infected.

“If it gets really wet, it just depends, because the ticks might be out there doing fine, but if fewer people are out there recreating or out in their garden they could be less Lyme disease,” Tsao said.

So far, the Upper Midwest’s spring conditions are looking relatively favorable for more ticks, but Tsao cautions that events throughout the season, such as abrupt droughts, make sweeping predictions difficult.

“The ticks always surprise us,” Tsao said.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us