Why Wisconsin Became A Pivotal Front In Nationwide Redistricting Fight

Prior to 2011, Milwaukee-area residents Marla Stephens and Kris Lennon felt that their votes counted. Now, however, they say the impact of their votes is diminished due to Wisconsin's 2011 redistricting — which is under challenge in a U.S. Supreme Court case.

June 1, 2018

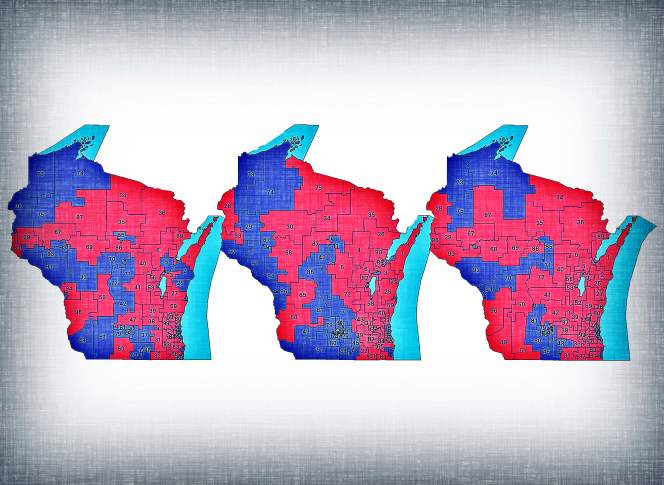

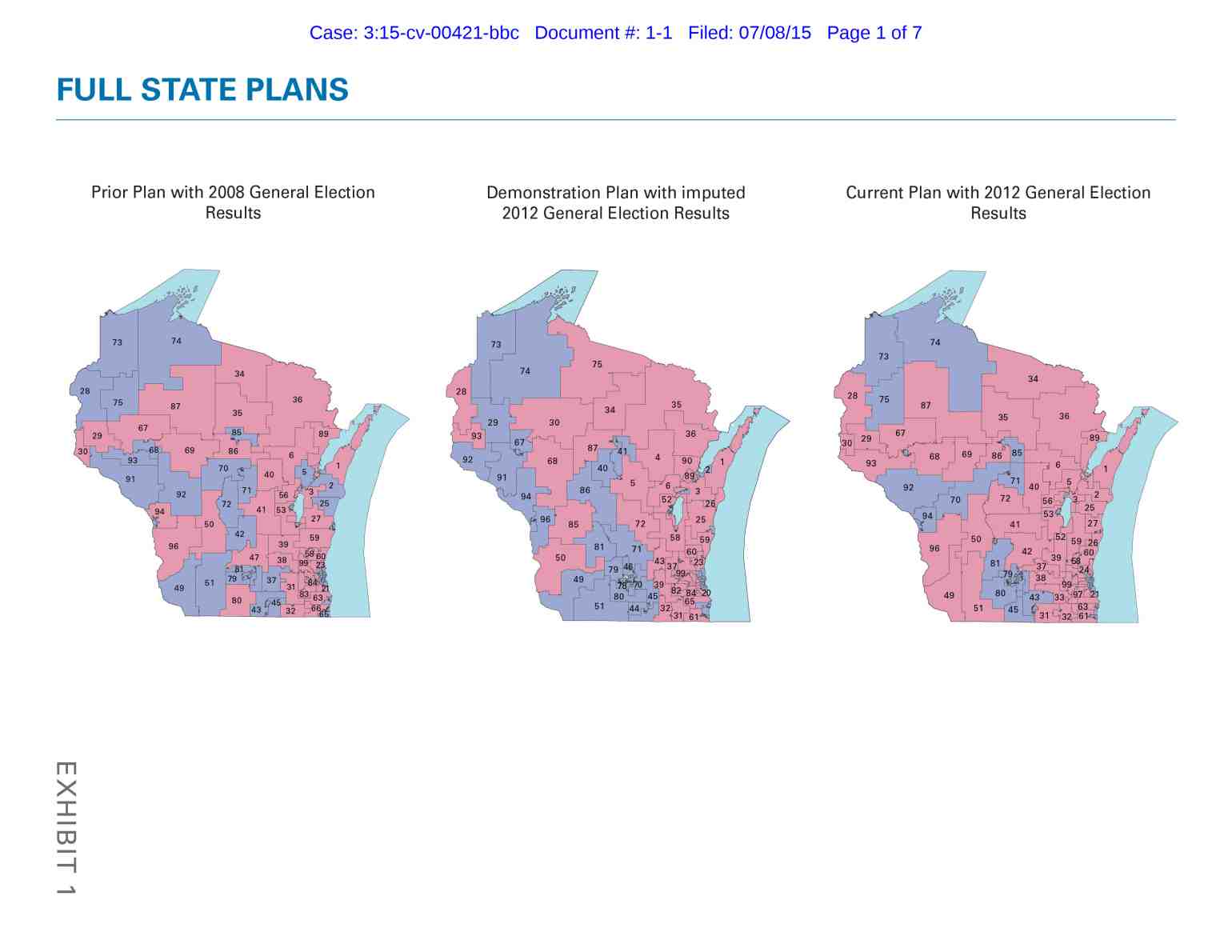

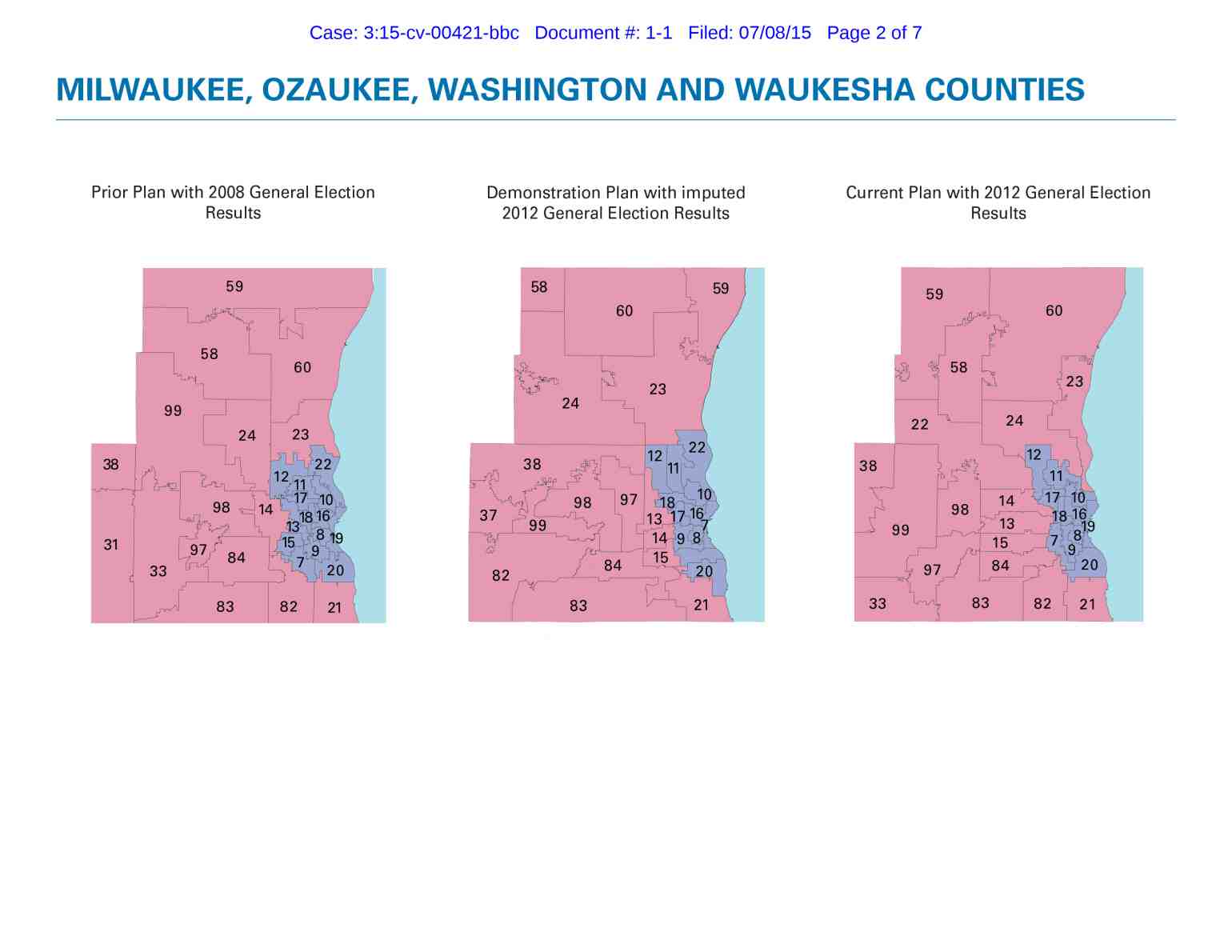

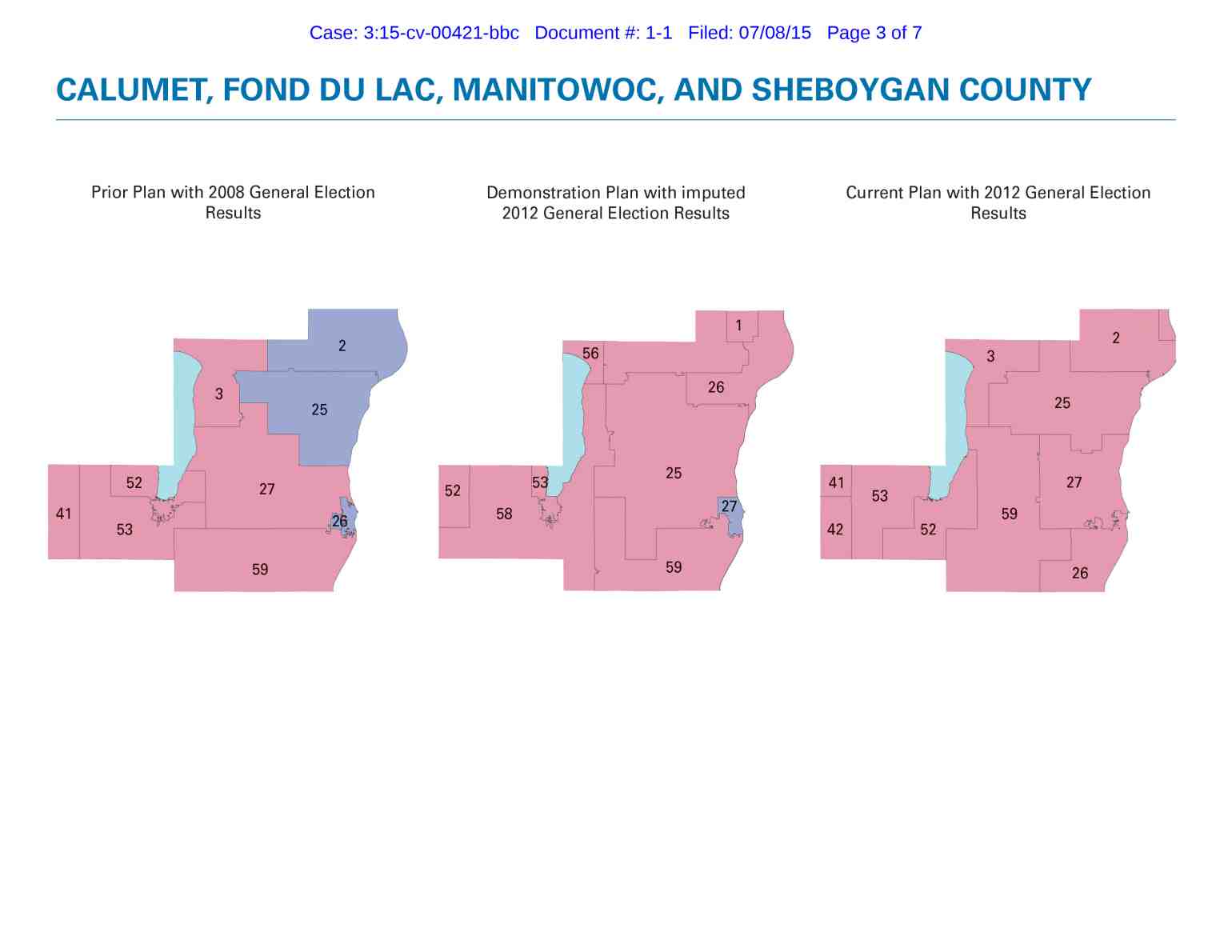

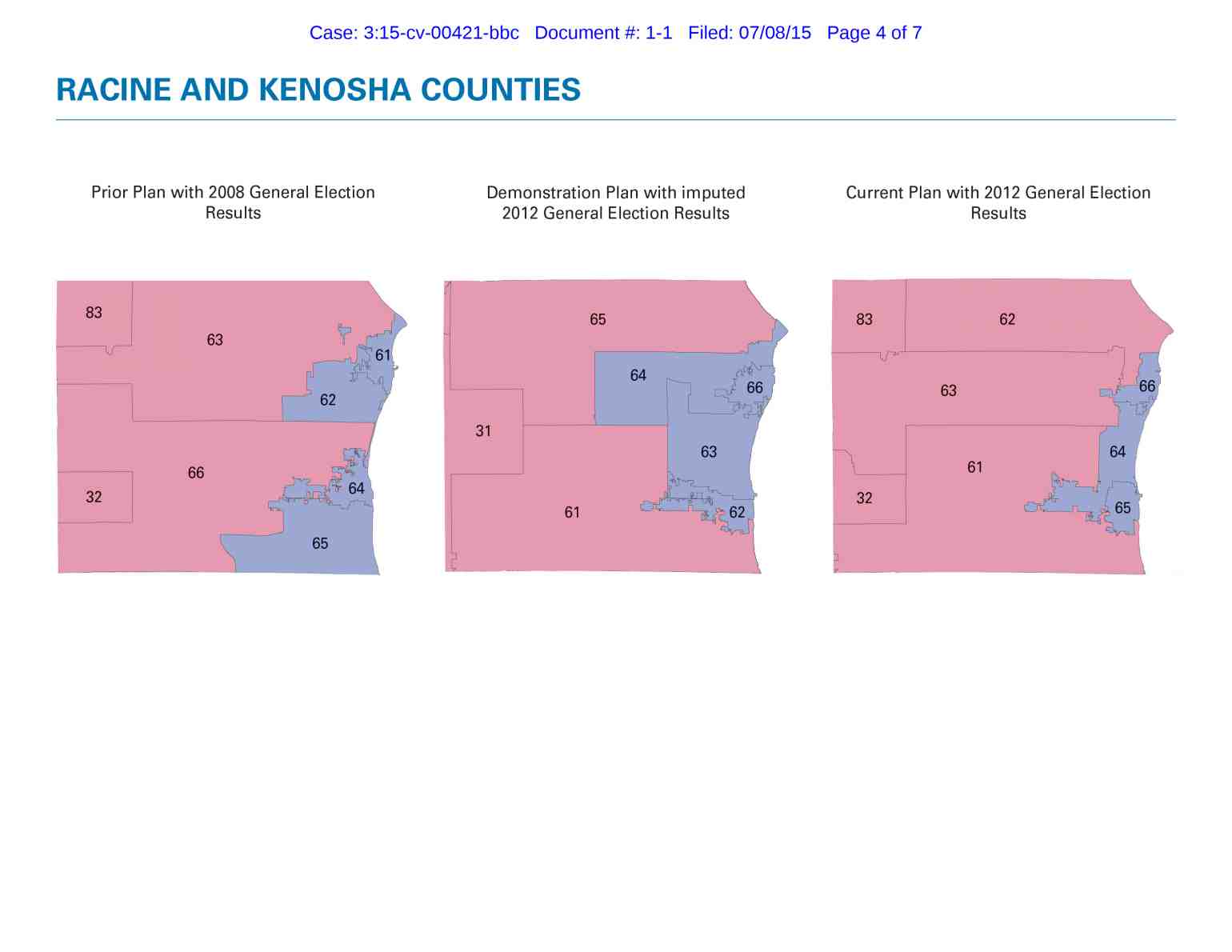

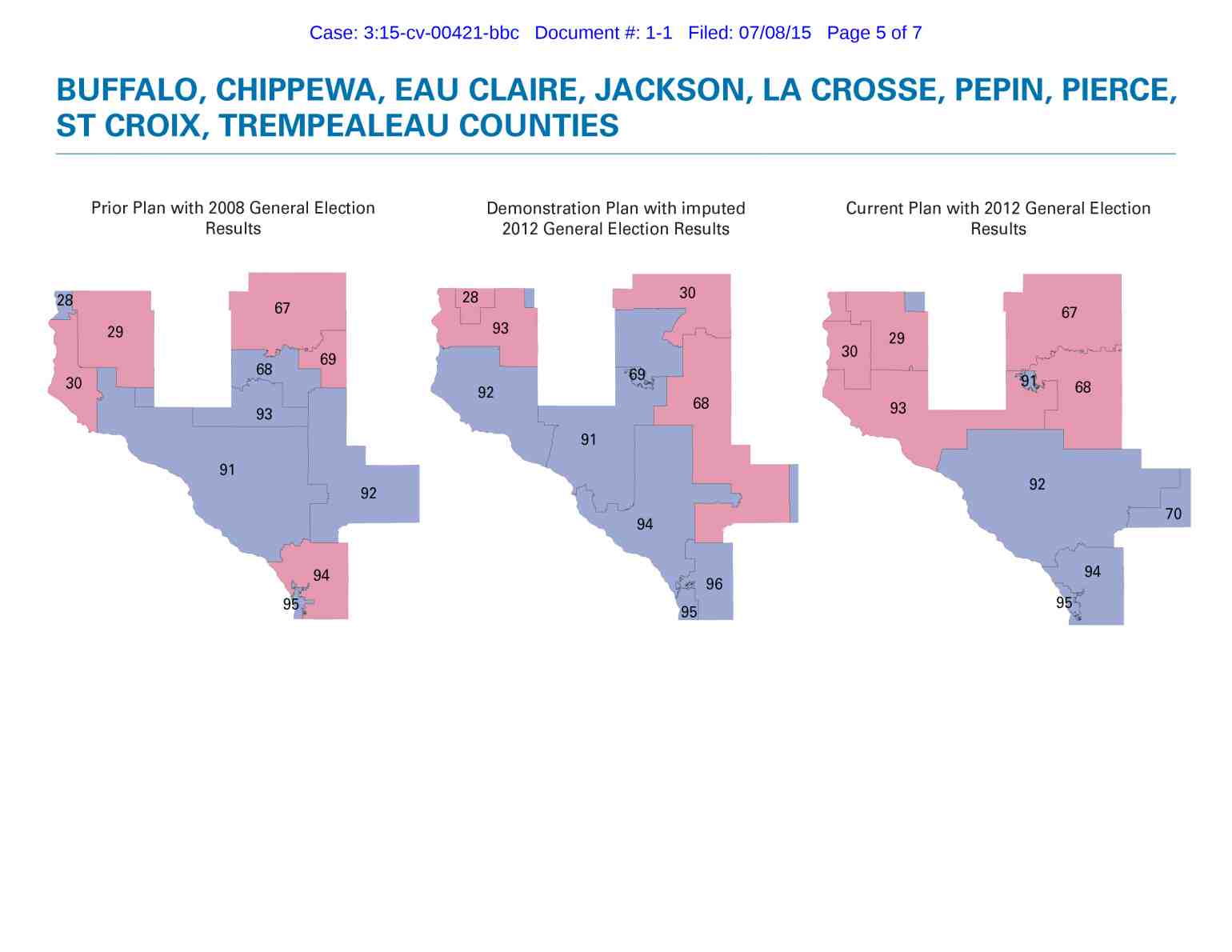

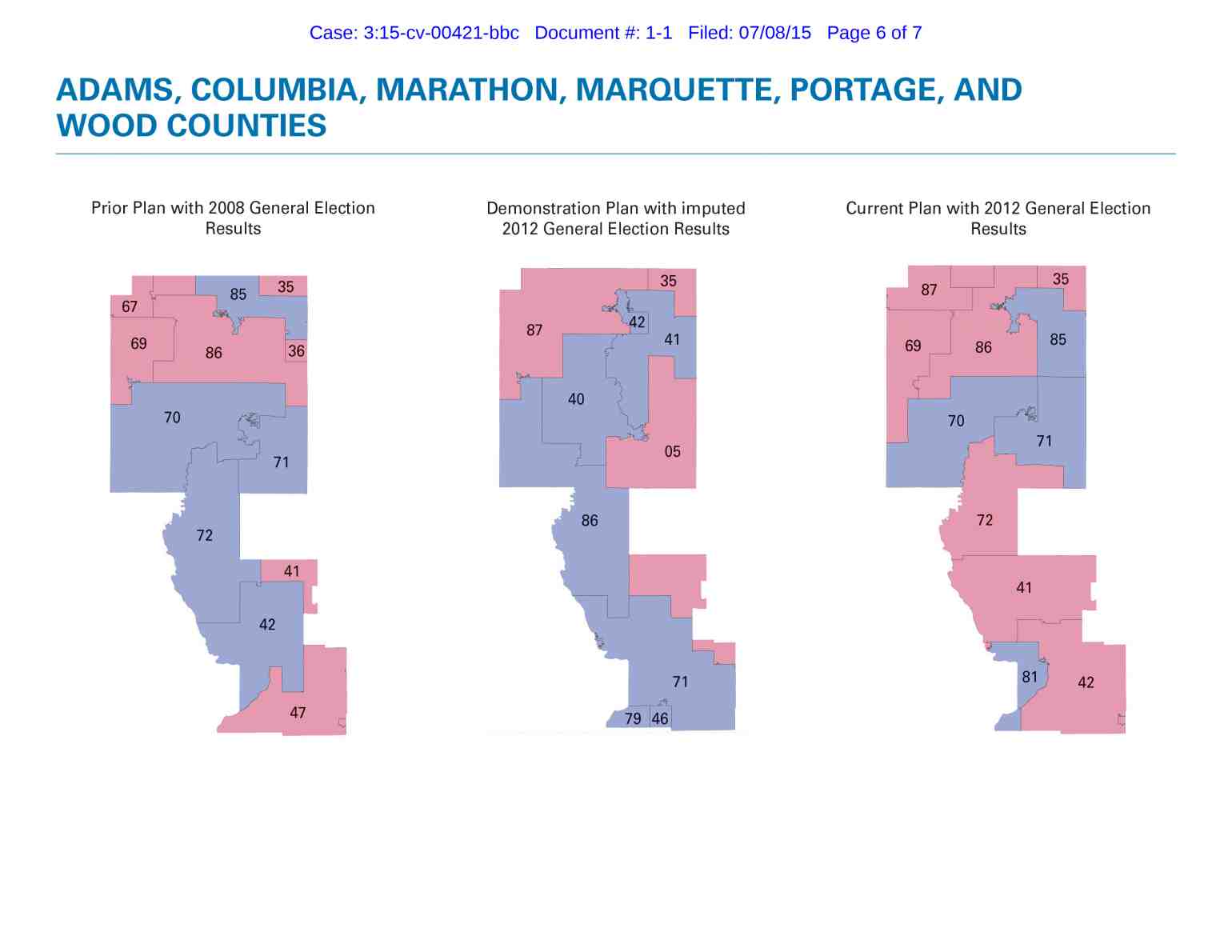

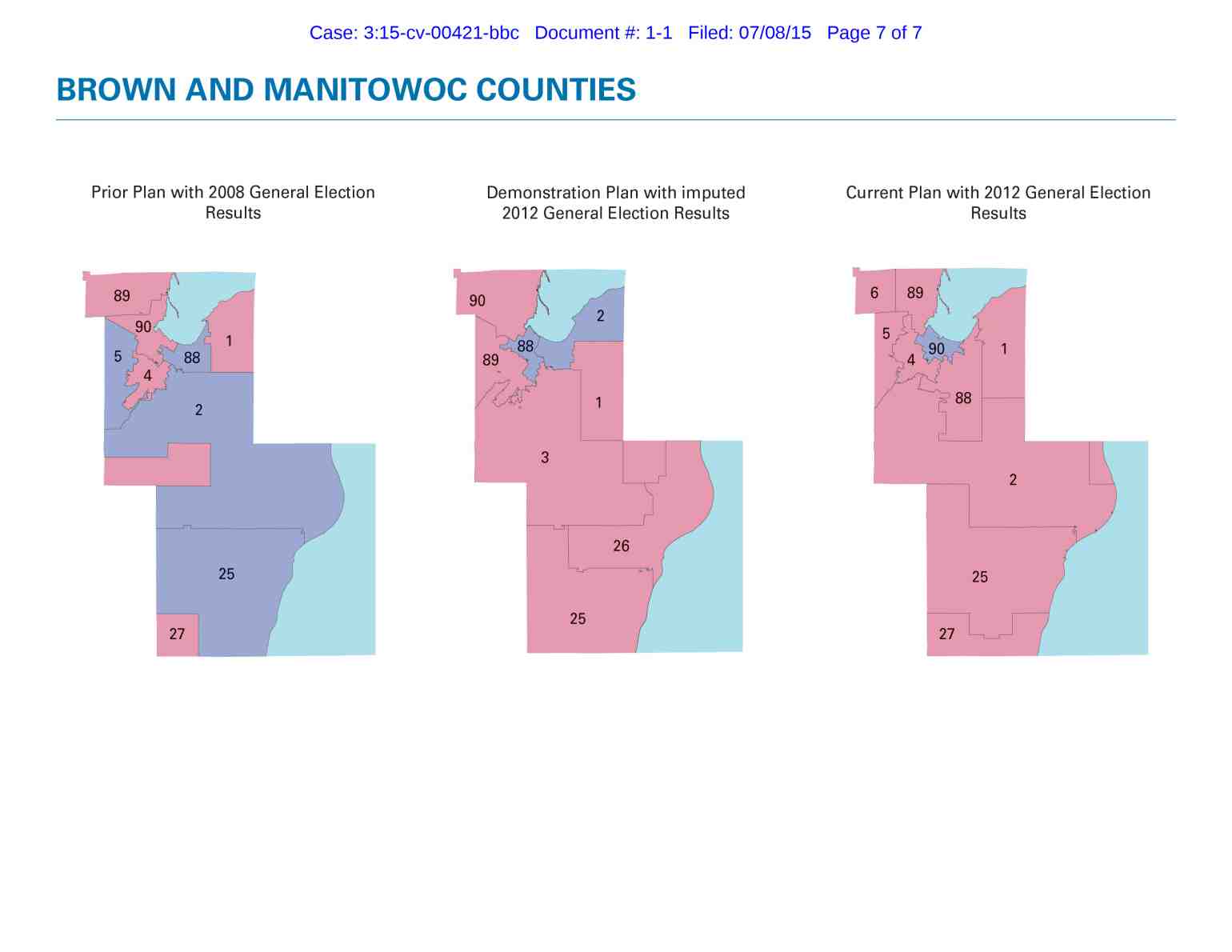

Wisconsin legislative districts pre and post 2011 maps with 2008 and 2012 election results illustration

Prior to 2011, Milwaukee-area residents Marla Stephens and Kris Lennon felt that their votes counted.

Now, however, they say the impact of their votes is diminished due to Wisconsin’s 2011 redistricting — which is under challenge in a U.S. Supreme Court case. A ruling could come any day, and the outcome, experts say, could profoundly affect the nation’s elections and democracy for decades.

Because of where the lines were drawn in redistricting, Stephens, a Democrat, now votes in a heavily Republican district, where her party has little chance of winning. And Lennon, an independent, now votes in a district that is so packed with Democrats that the winning party is virtually guaranteed even before the first ballot is cast.

Critics call the 2011 redistricting, which followed a Republican sweep of the state Legislature and governor’s office in 2010, an unconstitutional attack on the voting rights of Democrats in Wisconsin that violates the First Amendment’s protection of freedom of speech and association.

In addition, the plaintiffs in the lawsuit before the high court allege the redistricting violates the 14th Amendment’s equal protection under the law “because it treats voters unequally, diluting their voting power based on their political beliefs.”

In the 2010 fall general election, before redistricting, Republicans won 60 of 99 seats in the state Assembly after winning 57 percent of votes in races across the state. That win — part of a national Republican strategy known as REDMAP, the Redistricting Majority Project — allowed the GOP to control Wisconsin’s redistricting in 2011.

After that win, Republican legislators hired attorney Eric McLeod and the law firm of Michael Best & Friedrich to represent the Wisconsin Legislature and assist the Republican leadership in creating a partisan map favoring the GOP.

Republican party leaders left the Capitol building to create the new maps at the Michael Best firm across the street. The group, including legislative aides and a consultant, used past election results to design districts “that would maximize the number of districts that would elect a Republican and minimize the number of districts that would elect a Democrat,” according to the suit

Dale Schultz, who served as a Republican state senator during the 2011 redistricting, recalled that the map makers worked in a locked room where only Republican leaders were allowed in.

When the maps were completed, Schultz said, he was only shown what his own district would look like. A moderate increasingly out of step with the Legislature’s Republican majority, Schultz said he agreed to the map, believing that even if he said something, “nobody would do anything anyhow.”

Republicans were asked to sign non-disclosure agreements. Democrats, locked out of the drawing session, had no input on the new districts.

The Committee on Senate Organization introduced the maps on July 11, 2011. One public hearing was held two days later, on July 13.

The maps passed on a party-line vote. Republican Gov. Scott Walker signed the new legislative districts into law, less than a month after the bill’s introduction, on Aug. 9, 2011.

The redrawn lines have been the subject of court challenges ever since.

Matt Rothschild, executive director of the nonpartisan and nonprofit Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, called the secretive process a “grotesque” deprivation of people’s “First Amendment rights to speak and be heard.”

“They didn’t do the public’s business in public,” he said. “They didn’t do the public’s business in the Capitol.”

Schultz said he regrets voting for the redistricting. He knew that the majority party could gain power by controlling the redrawing of electoral districts. But the impact of that effort in 2012 “shocked” him, he said, as Democrats cast more ballots but Republicans enjoyed a “wave” election.

“And I just said, ‘That’s not right. There’s something wrong here.'”

The 2012 fall general election results showed a 174,000-vote margin in favor of Democrats running for Assembly; however, Republicans took the Assembly again, maintaining a hold on the majority with 60 of 99 seats but only 46 percent of the vote. In the 2014 fall general election, Republicans won 63 seats with only 52 percent of the two-party vote.

Schultz and former Democratic state Sen. Tim Cullen are now the co-chairmen of the Fair Elections Project Wisconsin campaign, which is dedicated to helping “end the partisan gridlock” by stopping partisan gerrymandering. These days, Cullen and Schultz work to garner support for a new, nonpartisan and independent redistricting process.

Decision in Wisconsin case key

In a decision that could come down any day, the nation’s highest court will decide a lawsuit challenging that redistricting, which originated in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin. There, a three-judge panel ruled in Whitford v. Gill (formerly known as Whitford v. Nichol and later Gill v. Whitford) that the 2011 map was “an aggressive partisan gerrymander that was both intended and likely to persist for the life of the plan” in which the “defendants intended and accomplished an entrenchment of the Republican Party.”

The decision marked the first time a federal district court ruled a state legislative redistricting plan as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. The defendants, members of the disbanded Government Accountability Board, appealed the decision to the Supreme Court.

The lead plaintiff, retired University of Wisconsin-Madison law professor William Whitford, argued the 2011 redistricting created “one of the worst partisan gerrymanders in modern American history.” A subsequent study of the 2012, 2014 and 2016 elections showed Wisconsin is not alone.

“Six states where Republicans had sole control of redistricting have statistically significant skews in all three elections: Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Virginia,” according to a 2017 study titled “Extreme Maps” by the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonpartisan law and policy institute focused on democracy and justice. “Three more states — Georgia, Tennessee and Wisconsin — show statistically significant skews in at least one election.”

Democrats have been faulted for their maps, too. The Brennan Center study showed “a notably high Democratic skew” in election results in Maryland and Massachusetts after redistricting by Democrat-controlled state governments.

A challenge to Maryland’s map is also before the U.S. Supreme Court. Although the court heard arguments in the Wisconsin and Maryland cases months apart, some experts have speculated it may release the decisions at the same time.

Standards for gerrymandering elusive

In past cases, the court has failed to agree on redistricting standards, said Thomas Wolf, an expert on redistricting and counsel with the Brennan Center.

In 2004, a fractured Supreme Court declined to rule in a Pennsylvania redistricting case after struggling to find “a judicially enforceable limit on the political considerations that the states and Congress may take into account when districting.”

Defendants in the Whitford case equated the plaintiffs’ argument to the one that failed in the Pennsylvania case, Vieth v. Jubelirer. They contended there is “no constitutional right for political groups to obtain a percentage of legislative seats corresponding to the percentage of votes their candidates earn statewide in legislative contests.”

Therefore, they argued, the 2011 maps are not unconstitutional simply because they result in a lack of “partisan symmetry” and what plaintiffs describe as “wasted votes” for Democratic candidates.

In addition, defendants claimed the disadvantaged groups in the 2011 plan are naturally packed geographically. They also argued that the Assembly redistricting plan drawn by a nonpartisan court after the 2000 Census would be unconstitutional under the efficiency gap threshold outlined by one of the plaintiffs’ experts, University of Wisconsin-Madison political science professor Kenneth Mayer.

The defendants called into question the standing of the plaintiffs to challenge the 2011 maps for the entire state, saying plaintiffs can only challenge the districts in which they live

Several factors influenced the Supreme Court’s past lack of decisions on partisan gerrymandering, according to Wolf. The court struggled to establish ground rules for redistricting because setting a standard for how elections are run can influence who gets elected.

Redistricting is traditionally a legislative activity, so the court hesitated to step in and put limits on an equal branch of government. A decision also requires questioning both election and constitutional law.

“The question isn’t so much whether they are constitutional or not,” Wolf said. “The question is when it is they become unconstitutional.”

The Whitford redistricting challenge is an important case because there are numerous states “where uncompetitive elections are undermining democracy,” said Brian Klaas, an expert on democracy and elections and co-author of How to Rig an Election.

The case is a “tipping point” because the Supreme Court could establish for the first time that the “deliberate manipulations of districts for partisan purposes is unconstitutional,” said Klaas, a fellow at the London School of Economics who has been sharply critical of President Donald Trump for what he describes as attacks on American democratic principles.

Klaas said the justices “may discuss the actual mechanisms by which districts are drawn … which sets an important precedent because of how they weigh in on whether it’s citizen-led commissions or legislatures or independent bodies, etc., that draw the districts.”

Report: Courts, commissions more fair

According to the 2017 Brennan Center study districts drawn by commissions, courts and split-control state governments “exhibited much lower levels of partisan bias.”

Prior to 2011, courts for many years were the de facto redistricting method in Wisconsin. In the past five state redistricting efforts, Wisconsin’s politically divided Legislature could not agree on one map. So every 10 years, the map ended up in the hands of nonpartisan judges.

But 2011 was different, said Cullen, the former Democratic state senator. That year, Republicans controlled the Legislature, and they used sophisticated software to “more precisely draw district lines to benefit the majority party and hurt the minority party,” he said.

“The simplest way to put it is the election in this legislative district was decided the day the map was drawn; it’s not decided in the November election,” Cullen said. “Legislators, by their vote, gave themselves a job for sure for 10 years. These races were decided.”

When redistricting becomes gerrymandering

District lines are usually redrawn after a census. According to the Brennan Center, the goal is to “ensure each district has about the same number of people and to fulfill the constitutional guarantee that each voter has an equal say.”

A 2017 report by the Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau, a nonpartisan state agency, said redistricting becomes gerrymandering when lines are drawn “by the party in power in a manner that intentionally discriminates and disadvantages the opposing political party … to ensure political gain.”

Gerrymandering can ensure safety for incumbents and lessen the power of some citizens’ votes; Schultz refers to the process as “rigged elections.”

“They create legislatures that are hard-right or hard-left that don’t really represent people as a whole,” Wolf said. “They prevent people from holding their legislators accountable because it’s incredibly difficult to vote them out of office.”

Partisan gerrymanders are created commonly through processes of packing and cracking, which result in “wasted” votes, according to the plaintiff complaint in Whitford.

In Wisconsin, for example, Republican legislators focused in 2011 on drawing district lines in a manner that packed as many Democratic votes into as few seats as possible. The cracking involved drawing the lines in a way that created new Republican majorities in districts by cracking apart areas dominated by Democrats.

Redistricting = lost vote?

Stephens, a Democrat and retired public defender, feels her voice has been lost — both in terms of the power of her vote and her ability to change the system. She and Lennon are members of the Citizen Action Organizing Cooperative, a group associated with Citizen Action of Wisconsin in which members pay an organizer to work on a fairer redistricting process.

Until 2015, Stephens lived in the village of Shorewood. It had been in Republican Sen. Alberta Darling’s district but was carved out and “packed” into Lena Taylor’s overwhelmingly Democratic Senate district.

Stephens hypothesizes that close votes in Darling’s pre-2011 district, such as in the 2008 fall general elections, threatened her incumbency. When “solid blue” Shorewood was removed from Darling’s district, her seat became safer, Stephens said.

Before redistricting, “We were seeing the ability to have some effect on how she [Darling] would vote because we had the ability to threaten her re-election,” said Stephens, who ran unsuccessfully for the state Supreme Court in 2011. “Now, we don’t. We are constituents she does not have to listen to. Her district is safe now.”

Stephens now lives in Whitefish Bay, a predominantly Republican district represented by Darling and Republican Rep. Jim Ott, where she believes her vote also has lost its power.

“We are often asked to call our legislators about a certain issue, and what you come to realize is that I can call my senator, I can call my assemblyperson 20 times a day, and my vote and the vote of people like me is not of any consequence to them,” Stephens said. “They know that they will be re-elected by ignoring me.”

Lennon, an independent, resides in the Riverwest neighborhood of Milwaukee, which is now part of an overwhelmingly Democratic district. The 2011 redistricting means that she and her progressive neighbors are represented by one Democrat, but more conservative surrounding areas are represented by multiple Republicans.

Her district has not been strongly affected because it was already heavily Democratic, Lennon said, but she fears the effect statewide.

“Currently, what you have are politicians choosing their constituents,” Lennon said. “Your vote can’t count without a fair map. And we can’t move forward with any laws or legislation that’s going to benefit the people without a fair map.”

Redistricting affects congressional elections as well. Nationwide, in 2012, Democratic candidates for the House of Representatives received 1.4 million more votes than Republican candidates, but Republicans gained a 33-seat majority in the House.

“It wasn’t that long ago Wisconsin had 10 representatives, and at that time, nine of the seats were competitive, and one was not,” Schultz said. “Now, we have eight, and none are competitive.”

According to the Brennan Center’s “Extreme Maps” report, gerrymandering provides Republicans with a 16- to 17-seat advantage in the House. Democrats would need to pick up 25 more seats to gain a majority there in 2018

REDMAP redraws America

Sophisticated digital mapping technology allowed Republican legislators in Wisconsin to draw lines favorable to the party. Technologies including Maptitude, RedAppl and autoBound are so advanced that legislators can draw lines down to the exact home. Mapping technology further allows legislators to view multiple versions and select the most favorable one.

Schultz recalled the redistricting process his mother, an attorney, assisted with as partner of a Madison law firm when he was a teenager. He walked into a conference room of her office to see four maps, all drawn by hand. He described the process of drawing even one map as a “Herculean task.”

Now, informative data about voters and their habits and computer programs that can draw maps in “five seconds or less” allow the majority party to “play [the redistricting system] like a piano,” Schultz said.

“It can be used to diminish the value of a person’s vote, and that’s what the lawsuit in Washington is really all about,” he continued. “It’s about an organized effort to diminish the value of certain votes.”

The use of technology to draw lines and create districts favorable to Republicans is part of a greater GOP strategy known as REDMAP, the nationwide effort to gain a Republican majority in state and national elections.

REDMAP allowed Republicans to gain 675 legislative seats across the United States following the 2010 election, laying the groundwork for 2011 redistricting efforts. Key victories were won in Wisconsin, Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Virginia.

The Republican State Leadership Committee spent $1.1 million in Wisconsin in an effort to establish a Republican majority in the Legislature, including approximately $500,000 to target Democratic Senate Majority Leader Russ Decker, who was defeated by Republican Rep. Pam Galloway.

“If you can stack a legislature in this way, what incentive is there for a voter to exercise his vote?” asked Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg during oral arguments for the Whitford case. “Whether it’s a Democratic district or a Republican district, the result — using this map — the result is preordained in most of the districts … I mean, that’s something that this society should be concerned about.”

‘You still have the right to vote’

Rick Esenberg, founder and president of the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty, views redistricting as inherently political. No matter what, elected officials will fight for self-preservation by drawing maps that are favorable to their party, said Esenberg, whose group supports the rule of law, individual liberty, constitutional government and a robust civil society.

Esenberg acknowledged that electing a candidate can be difficult for the minority political party in certain districts, whether it is due to partisan redistricting or a high geographic concentration of party supporters that occurred naturally.

But he cited the January special election in state Senate District 10 as an example of how voters can triumph in a district in which the other party has a majority. Democrat Patty Schachtner won the Republican-leaning district over Republican state Rep. Adam Jarchow, a result that pundits said is part of a potential “blue wave” of Democratic victories in 2018.

Esenberg thinks the power of digital mapping technology, the ability of politicians to accomplish partisan gerrymandering and the impact of disenfranchisement are overstated.

“I don’t think that [politicians] eliminate the power of individual votes,” Esenberg said. “You still have the right to vote.”

Could decision bring two parties together?

Experts speculate the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to take on the Maryland case may be aimed at insulating the court from charges of bias. Chief Justice John Roberts noted the political overtones of the court’s decision during oral argument in the Wisconsin case.

“If you’re the intelligent man on the street, and the court issues a decision, and let’s say, okay, the Democrats win, and that person will say, ‘Well, why did the Democrats win?'” Roberts said.

“And the intelligent man on the street is going to say … it must be because the Supreme Court preferred the Democrats over the Republicans. And that’s going to come out one case after another as these cases are brought in every state. And that is going to cause very serious harm to the status and integrity of the decisions of this court in the eyes of the country.”

Klaas said the decision could force Wisconsin lawmakers to work toward a more fair redistricting system.

“I think that if the Supreme Court sets a precedent that says ‘Look, this redistricting process was fundamentally unconstitutional,’ that both parties should come to the table and say ‘Okay how can we do this so we’re going to be happy no matter who is in charge of the redistricting process?'”

The timing of the decision makes it difficult for new maps to be drawn before the August primaries and the November general election, but new maps could be in effect for the 2020 elections if the court upholds the Wisconsin district court’s decision.

“It’s my fondest belief that Supreme Court justices will do the right thing, not the partisan thing, because they have lifetime appointments,” Schultz said. “I want to believe in that because not believing in that is a scary sort of proposition.”

This story was produced as part of an investigative reporting class in the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication under the direction of Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism managing editor Dee J. Hall, the Center’s managing editor. The Center’s collaborations with journalism students are funded in part by the Ira and Ineva Reilly Baldwin Wisconsin Idea Endowment at UW-Madison.

“Undemocratic: Secrecy and Power vs. The People” examines the state of Wisconsin’s democracy in an era of gerrymandering, secret campaign money, restrictive voting laws and legislative maneuvers that weaken the power of regular citizens to influence government. The series was reported by University of Wisconsin-Madison journalism students Cathleen Draper, Nicole Ki, Pawan Naidu, Cameron Smith, Teodor Teofilov and CV Vitolo-Haddad as part of an investigative reporting class led by Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism Managing Editor Dee J. Hall with assistance from Coburn Dukehart, the Center’s digital and multimedia director. More stories will be published in upcoming months.

The public is invited to help with this investigation of the state of democracy in Wisconsin. Have you been harmed by a lack of democracy? Send ideas for coverage to [email protected], or WCIJ, 5006 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave., Madison, Wis., 53706. The best tips clearly describe the issue and include documentation or other evidence.

The nonprofit Center collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us