What Does The Passenger Pigeon Have To Do With Lyme Disease?

Though the passenger pigeon went extinct a century ago, could its absence have repercussions that are being felt in the 21st century?

July 26, 2018

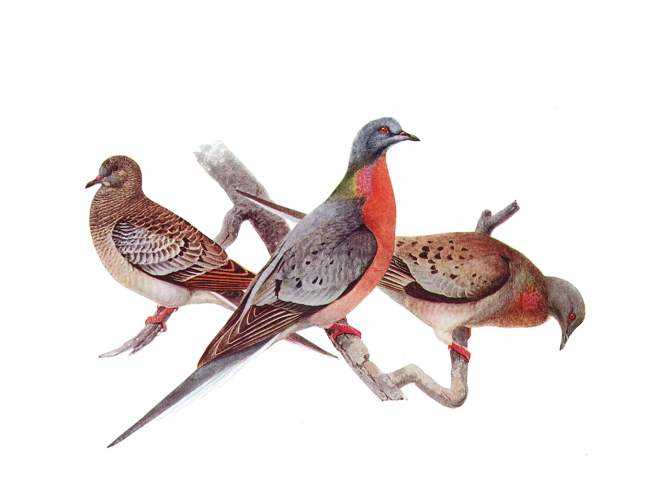

Passenger pigeons illustration from "Birds of New York"

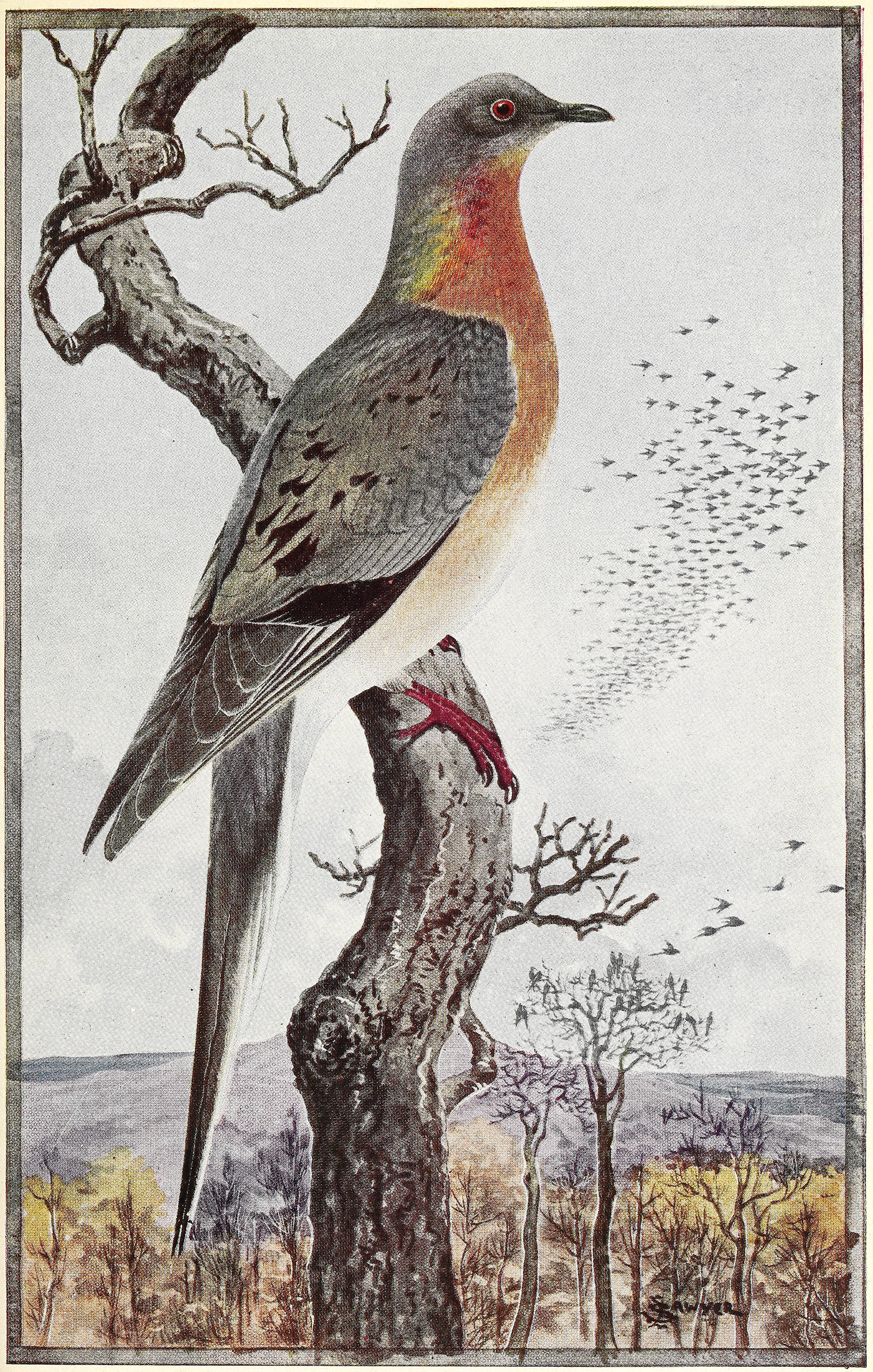

“The feathered tempest roared up, down, and across the continent, sucking up the laden fruits of forest and prairie, burning them in a traveling blast of life,” wrote naturalist Aldo Leopold in A Sand County Almanac.

But within a few decades of 1871, when the largest recorded flock of passenger pigeons (Ectopistes migratorius) roared into central Wisconsin to nest, they were gone forever. In 1914, the last passenger pigeon died in captivity.

Though this species went extinct a century ago, could its absence have repercussions that are being felt in the 21st century?

David Blockstein, a passenger pigeon researcher and senior adviserat the Association for Environmental Studies and Sciences, pondered this issue closely, and turned his thoughts to a contemporary malady — Lyme disease — that has become increasingly prevalent in recent decades.

Blockstein was reading a 1998 article by disease ecologist Richard Ostfeld in the journal Science about ecological factors relating to Lyme disease that prompted a question. Ostfeld was unraveling a web of interactions between acorn production, gypsy moths, deer, white-footed mice and black-legged ticks (Ixodes scapularis), which are responsible for transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria that cause Lyme disease in North America.

In “mast years,” when oak trees produced a bumper crop of acorns, mouse and deer populations soared. So did the density of black-legged ticks, leading Ostfeld and his colleagues to suggest that the risk of Lyme disease would spike in the year following a mast event.

“When I first read this, I thought, wow, this is a really great piece of work identifying this complex system, and there’s another element — and that’s the passenger pigeon,” Blockstein said.

So Blockstein responded with a letter to Science, in which he suggested that passenger pigeons would have descended during mast events, devouring acorns and depriving white-footed mice and other species of much of their food supply. Is it possible, he asked, that the explosion in mice populations would have been less likely had the birds not been hunted to extinction?

His hypothesis has gotten some attention over the years.

“My argument doesn’t claim that the presence of passenger pigeons prevented Lyme disease,” Blockstein said. “My argument is that if passenger pigeons still existed, this increase of Lyme disease would not be taking place — at least in those local spikes. The disease may have continued to spread for other reasons.”

Blockstein pointed to the broader issue raised by his speculation.

“The discussion is most useful to answer the question of ‘what are the consequences of extinction and what good is it to have these species?’ My argument is yes, here is a case where arguably people’s health today is affected by an extinction that took place more than a century ago,” he said.

Blockstein acknowledges that the problem with historical inferences like this idea, though, is that there’s no way to test them.

Even so, it provides an opportunity to consider the unforeseen consequences of human intervention in the environment, he said.

“There are other ecological impacts of the extinction of the passenger pigeon. Even given a lot of caveats about environmental change, it is still an argument that’s grounded in science and ought to make people stop for a second and think about how what we do to the environment can have negative consequences a long, long time later,” Blockstein said.

The abundance and extinction of the passenger pigeon

David Blockstein began studying passenger pigeons while he was a Ph.D student at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities. He received his bachelor’s degree from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and returned to do post-doctoral research with Stanley Temple, now a professor emeritus in the Department of Wildlife and Forest Ecology at the university. Blockstein was a major contributor to the Passenger Pigeon Project in 2014, commemorating the centennial of the bird’s extinction. He also wrote the chapter about the passenger pigeon for The Birds Of North America, published by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

“At the time of the passenger pigeons, they were so abundant. There were an estimated five billion of them, and they were highly mobile. There were so many of them and they moved around so quickly that this buildup of acorns would result not in an increased population of deer and mice, but in passenger pigeons coming in and eating up the acorns. In those cases, that would mean that this spike in Lyme disease would just not happen,” Blockstein said.

The idea that passenger pigeons could have, and probably did, clean out local populations of acorns is well established in the historical literature, Blockstein said.

“For example, back in the colonial days people would let their hogs go into the woods to fatten up, and there are a couple of examples of hogs starving after the passenger pigeon flocks came by. When you have a flock that was at least hundreds of millions, there’s not much food that will be left,” he said.

Wisconsin figures prominently in the story of the passenger pigeon.

In 1871, as many as one billion of the birds nested in a 850-square mile swath of central Wisconsin, stretching in a “V” shape from Black River Falls south to Wisconsin Dells and back north to Wisconsin Rapids, Temple said in a 2014 presentation at UW-Madison. It was the largest passenger pigeon nesting on record, and it drew at least 100,000 commercial and other hunters to Wisconsin.

Wherever passenger pigeons settled in for a month of nesting, they “literally were sitting targets,” Blockstein said.

The market for passenger pigeon meat was enabled by two technological forces, the railroads and the telegraph, Blockstein said. By the mid-19th century, most of eastern North America was within a day’s ride of a rail line by horseback or wagon. When pigeons nested, word spread via telegraph, and pigeon hunters would themselves flock at the site, shipping back of barrel after barrel of pigeon carcasses to major urban areas. It was an extremely lucrative trade — while it lasted.

An 1875 illustration depicts hunters shooting at a passenger pigeon flock in northern Louisiana.

“I don’t use the term ‘hunting’ to describe the extinction,” Blockstein said. “The hunting that took place in the late 19th century was commercial killing.”

Passenger pigeons’ survival strategy of flying en masse to thwart predators made them vulnerable to humans. Intensive hunting disrupted their breeding grounds, and pleas to enact conservation laws to protect them amid the slaughter went largely unheeded. The disappearance of the species led to the enactment of the Lacey Act of 1900, which established interstate regulations and prohibitions on taking and selling wildlife, fish and plants. It was the first federal wildlife protection law in the United States, but it came too late for what had been the most abundant bird species in North America, if not the world.

Martha, the last surviving member of the species, died in captivity at the Cincinnati Zoo on September 1, 1914. It is widely believed that she was born in Wisconsin and was part of a captive flock kept by an amateur aviculturalist named David Whittaker. According to an account by naturalist Joel Greenberg, Whittaker sold his flock in 1896 to biologist Charles Otis Whitman at the University of Chicago. By 1907, all of Whitman’s birds were dead, save for Martha, the one he had sent to Cincinnati.

Extinction and the long arc of consequences

Richard Ostfeld of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies calls the idea about passenger pigeons and Lyme disease a “friendly amendment” to his research on the connection between acorn mast events and the risk of infections.

“The notion that a seed predator could appear in potentially the millions of birds moving from rich foraging area to rich foraging area [and] could circumvent these boom years is plausible,” Ostfeld said. “Unfortunately, we’ll never know because we drove that species extinct.”

Acorns are unusual because they occur in a boom-and-bust cycle, Ostfeld said, one that correlates with fluctuations in the population of mice.

“If passenger pigeons were intercepting most of those acorns,” he said, “that does not mean mice would go away. Mice would probably be more constant in their abundance, but they wouldn’t go away. Hence, Lyme disease wouldn’t go away either.”

The broader point, Ostfeld said, is “that when we drive species extinct, we often don’t have a clue what the consequences might be. In terms of utilitarian functions, when these species go extinct, we may be losing important services that they provide — but we don’t know — because they’re gone.”

However, any role passenger pigeons played in keeping Lyme disease in check might not have been evident given other factors relevant to the disease, he said. For example, until forests in the northeastern U.S. became highly fragmented, the disease was less prevalent, and its full etiology wasn’t identified until the late 20th century.

Ostfeld and his colleagues have collected and analyzed decades worth of data from their forest research plots in upstate New York, deepening their understanding of the complex interplay of ecological factors that contribute to the spread of Lyme disease infections in humans.

The work that sparked ornithologist David Blockstein’s interest also included the role of the gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar), a notorious and destructive invasive pest with a particular appetite for oak trees. The moths are not native to North America; they were imported in the mid-19th century in hopes they would be a hardier replacement for the silkworm moth. But in the late 1860s, a few escaped into the landscape around Medford, Mass., where they were being bred. Within 10 years’ time, their devastating potential was clear.

In his 1998 paper, Ostfeld demonstrated a link between acorns, mice populations and gypsy moths. More acorns meant more food for mice, resulting in a population increase. Mice also feed on gypsy moth pupae, so in times of acorn abundance, the mouse population increased and the gypsy moth population decreased. But because the mice are also key hosts for black-legged ticks, the risk of Lyme disease increased.

A new round of Ostfeld’sresearch findings, published in the journal Ecology in May 2018, uses nearly 20 years of data to examine the role of predators, such as coyotes, bobcats and foxes, in the transmission of Lyme disease. He concluded that greater diversity of predators in an area results in a lower prevalence of nymphal (immature) ticks, which typically transmit Borrelia bacteria to humans.

“If you have these smallish predators like foxes or bobcats or opossums, they’re protecting us. When coyotes come in, they evict them. Then the protective effect goes away,” Ostfeld said.

While the hypothesis about passenger pigeons and Lyme disease is plausible, he reiterated that it’s impossible to investigate.

“These systems are inherently very noisy,” Ostfeld said. “They’re complex as anything and you definitely want to avoid having the noise drown out the signals. You have to focus on big signals, and the potential is for the passenger pigeon to have imposed a big signal, but we’ll never know.”

Blockstein speculated that it’s unlikely that passenger pigeons would exist today, given their biology and the social pressures of modern agriculture. Nevertheless, he said, it’s worth considering as an object lesson about human impact on the environment.

“The loss of a check on local increases of Lyme disease is a way that the unsustainable habits of our forebearers are coming back to bite us,” Blockstein said.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us