The Revolving Door Of Disease Between Humans And Animals

Charting the animal origins of human diseases like COVID-19 can be difficult and often leads to unexpected discoveries.

April 28, 2020

Mahal at Milwaukee County Zoo illustration

When initial reports about what would come to be called COVID-19 made their way around the world in January 2020, the emergence of the novel coronavirus that causes the illness was a mystery. Within weeks, its earliest identified cases were believed to be connected with a live-animal market in Wuhan, China, but the precise path the virus took to infect people in the densely populated city remains unclear.

Charting the animal origins of human diseases like COVID-19 can be difficult and often leads to unexpected discoveries, explained Dr. Tony Goldberg, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine. During a January 29, 2020 presentation at the Wednesday Nite @ the Lab lecture series on the UW-Madison campus, Goldberg recounted the growing body of research into pathogen transmission between animals and humans over the past three decades.

“This can be attributed to the remarkable story of the origins of AIDS,” Goldberg explained in his lecture, recorded for PBS Wisconsin’s University Place. “In the early 1990s, we discovered that AIDS was a virus that originated from chimpanzees in central Africa… to me, the HIV pandemic is the mother of all pandemics, and the mother of all diseases of zoonotic origin.”

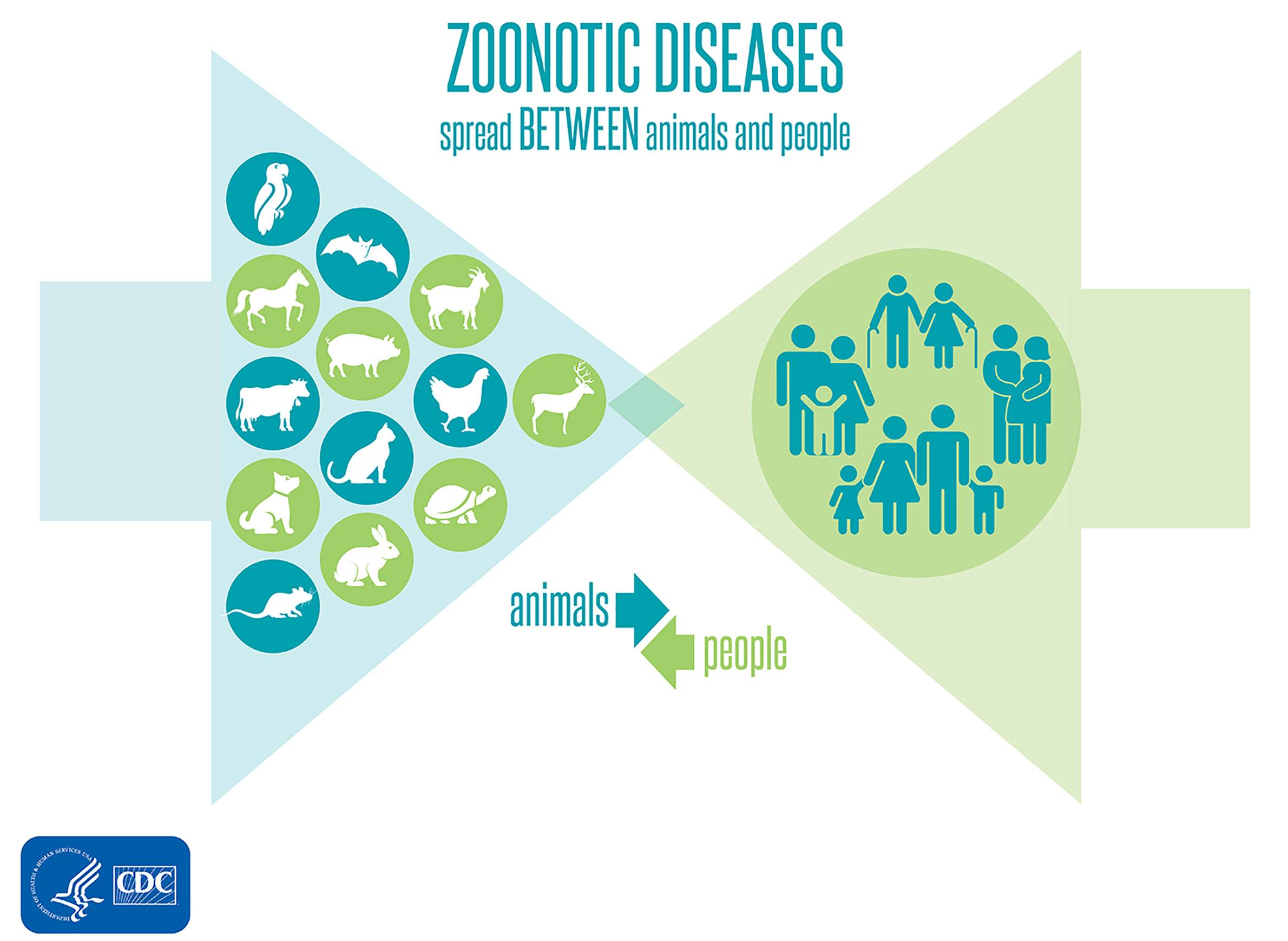

Although the transmission of zoonotic diseases, which are illnesses that move from animals to humans, is a primary focus for many researchers, Goldberg focused on pathogens that can pass from humans to animals and between different species.

While studying a community of chimpanzees at Kibale National Park in Uganda, Goldberg encountered a mysterious respiratory illness that caused numerous deaths within the group’s population. Researchers working with the primates initially responded with an abundance of caution and wore protective gear to avoid contracting the potentially zoonotic disease. However, tests revealed the chimpanzees were infected with rhinovirus C, the same type virus that causes common colds in humans. They had likely contracted it due to their proximity to humans.

The ability to identify unknown pathogens has developed alongside genomic research; efforts to map animal DNA have allowed researchers to apply a set of techniques known as metagenomics when faced with an unspecified illness. With a complete genome sequence of an animal, scientists use metagenomics to study a tissue sample and identify everything present that is not part of the animal’s genetic code.

“Most of it will be your salamander or your person or your chimp, but hiding in there, kind of the proverbial needle in a haystack, will be the thing you’re looking for, and you don’t have to have any prior knowledge of what it is,” Goldberg said. “These techniques are sometimes called agnostic or unbiased, and they’re very powerful. They’re the future of infectious disease diagnostics.”

Even as identifying infectious agents has grown more common in recent years, tracing paths of transmission remains difficult. Wisconsin River Eagle Syndrome, a set of symptoms that includes sudden seizures and death in the state’s bald eagle population, remained a complete genetic mystery for many years. Eventually, using metagenomics, a new illness called bald eagle hepacivirus was identified as a possible culprit.

While the virus was detected in bald eagles around the United States, those in Wisconsin are nine times more likely to carry the virus, and eagles living along the Wisconsin River 14 times more likely. Researchers largely ruled out genetic transmission from parents to offspring, but suspected local cycles of transmission that Goldberg said appeared to be decoupled from the host birds and instead are related to their surrounding environment.

A variety of parasites and pathogens pass between multiple species as part of their life cycle, with their effects on carriers ranging from harmless and undetectable to highly visible and severe depending on the stage of development and the species infected. One such zoonotic pathogen is Yersinia pestis; the bacteria spreads via the life cycles of host fleas and rodents, and manifests as the historically devastating plague in humans.

As for human actions, global commerce, particularly agriculture and trade in animals, can enable novel transmissions between organisms, Goldberg explained. Unexpected human health impacts that result can be difficult to prevent or trace to their source.

“We really do have to worry about emerging infectious diseases, and there are more and more of them every year. I guarantee you that [COVID-19] will not be the last… that any of us see,” Goldberg said.

Key facts

- Zoonotic diseases are illnesses that pass from animals to humans, and the transmission of illnesses from humans to animals is sometimes called reverse-zoonosis.

- Metagenomic techniques involve mapping a full genomic sequence of a species, then sequencing the contents of a tissue sample from an individual of a genetically mapped species and eliminating all of that animal’s DNA to identify any foreign genetic material present, including pathogens.

- Chimpanzees are susceptible to multiple human respiratory pathogens. One reason is that the species’ genome includes the host cell receptor CDHR3, which all humans have as well. This allele is critical to human health, and has two identified versions. The most common type helps resist infection, but the rare version makes people more susceptible to rhinovirus C infections and comes with a 10-fold increase in risk for developing asthma. Chimpanzees exclusively have the second type.

- Mahal was a 5-year-old orphaned orangutan in the Milwaukee County Zoo who died suddenly of a respiratory illness in December 2012. Tony Goldberg was asked to sequence a tissue sample to uncover the source of infection. He found genetic indicators of a newly discovered South African tapeworm, although the orangutan showed no signs of this parasite in his intestines. Rather, Mahal had died of cysticercosis after ingesting tapeworm eggs shed from an ermine while being transported between zoos. Tapeworm eggs are generally harmless to the mice and other small animals who consume them from the soil, and the mature worms reach their eventual hosts when these hosts are eaten by larger animals. When these predators directly consume the eggs, a stage of tapeworm development is skipped, and can result in the parasites growing out of control in the host and forming fatal cysts. This incident prompted concerns around the threat emerging zoonotic pathogens pose to people.

- Bald eagles are highly susceptible to West Nile virus, and the illness took a toll on these and other birds when the pathogen arrived in the United States in 1999. While human infections are widely caused by bites from carrier mosquitos, bald eagles contract the disease by eating infected eared (or black-necked) grebes, another type of bird.

- Wisconsin experienced an outbreak of monkeypox in 2003. It reached the state when Gambian pouched rats were imported to Texas from Ghana, and then included in a shipment of pets sent to Indiana and Wisconsin.

- Goldberg briefly garnered national headlines in 2013 when an unsequenced species of tick (in the Ambylomma genus) was discovered in his nose. He likely picked up the pest while working with chimpanzees in Africa. After its discovery, he reviewed images of baby chimps and noticed around 20% of them had similar ticks in their noses. Goldberg said this prevalence is likely because social grooming practices among the animals leave ticks vulnerable in fur or an exposed skin, but nostrils provide a warm and blood-rich environment for uninterrupted dining.

Key quotes

- On the movement of illnesses between animals and humans: “Infectious diseases don’t care which direction they go in. We’re concerned about human health because we’re humans, but they’re just as happy to go in the other direction. And they’re just as happy to go to other places, like Wisconsin.”

- On the variety of emerging pathogens: “I don’t want to give you the impression that all emerging infections or all new infections are viruses. These days, listening to stories about [COVID-19], you would think so, or Ebola, but they’re not. There are some weird ones out there.”

- On lessons from primate research in Africa: “[The chimpanzees have] only recently been exposed to these common cold pediatric viruses of people, and they’re exquisitely susceptible… This concept is actually called reverse zoonoses… there are plenty of diseases that go from people to animals, and they present a global threat to domestic animals and wildlife.”

- On working with sick animals: “We recently did an analysis of causes of death over the decades of [the Kibale] chimpanzee population and found that respiratory disease, which was a little surprising to us, accounted for over half of the documented deaths during the time that we’ve been able to follow these chimps daily… Being there, it was very scary because when chimpanzees are coughing and sneezing and dying, you’re not sure what’s killing them. So in situations like that, you have to be very careful about wearing personal protective gear.”

- On Wisconsin River Eagle Syndrome: “So where we are right now is sort of in the murky waters of emerging infectious disease. We found an interesting virus in an interesting species, infected or suffering an interesting disease, but we are moving towards testing the idea that this is actually the cause or not. It could be the cause, it could be an incidental finding, but a very interesting virus in an iconic species”

- On preventing pandemics: “It’s one of the unfortunate aspects of being an epidemiologist that when you do your job, nobody notices, because if you prevent an epidemic or prevent a pandemic, how does anyone know? It’s only when something breaks out that people say, ‘Well, you should be doing your job.’ Well, I prevented seven pandemics last week, what do you expect of me?”

- On a vaccine for COVID-19: “You may have heard in the news that scientists are rushing to develop a vaccine. That’s great, but that’s not an outbreak response; that vaccine will be ready for the next outbreak. The honest truth is that there are no magic bullet solutions for halting pandemics in their tracks. Once they’ve started, they keep going.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us