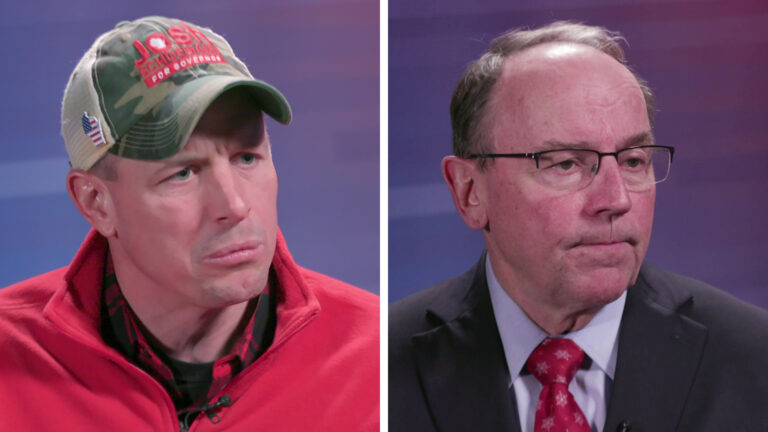

Charles Franklin on the Marquette Law School Poll's accuracy

Marquette Law School Poll Director Charles Franklin describes how he got started in political polling, accuracy and error rates of his poll, and how both doubt in and expectations of polls have grown.

By Marisa Wojcik | Here & Now

September 25, 2024

VIDEO TRANSCRIPT

Marisa Wojcik:

What got you into polling?

Charles Franklin:

Well, that goes way back. As a kid, I got interested in politics, and when the 10th grade was required to do a science fair project — Westinghouse Science Fairs. I decided to do a poll, a survey of second, fourth, and sixth graders. And so I go way back to the 10th grade in my polling career, and did another one in the 12th grade, and then in college became a political science major, and was interested in polling from then on.

Marisa Wojcik:

It's a little rare for someone so young to be interested in polling.

Charles Franklin:

Yes, a very nerdy kind of thing to be interested in. As a little kid, I was interested in science. I always said "I want to be a nuclear physicist." But as I got into middle school, I just thought human behavior was more interesting and the questions about politics and psychology were compelling. That was period of the Civil Rights Movement. There was lots of politics going on. And so I drifted into that, especially once I found out that psychology or political science could be a real scientific discipline, but it dealt with humans instead of add chemical A to chemical B and see if it turns blue, which I erroneously thought was what chemistry was about.

Marisa Wojcik:

Fast forward, I'm not gonna guess how many years...

Charles Franklin:

That's good.

Marisa Wojcik:

...but, 538 has listed the Marquette Law School Poll as number three in the country, what does that mean to you?

Charles Franklin:

Well, it's very satisfying. You know, we're a very small operation compared to the New York Times or the Washington Post or CNN. And so, that we in these 12 years have established that not just reputation, but the actual empirical evidence that our accuracy rates us third in the country out of some 500 pollsters. That's very gratifying. We've clawed our way up. When we first started doing the poll, the early rankings put us in the upper teens, and then we broke the top 10, and we were in the top five in the last rankings, and now number three this time. So I think it's a recognition that our work has been accurate, and accurate compared to a host of worthy competitors out there as well. And I have to add in one of the toughest states in the country where our races are so close — over the whole history of the Marquette poll, our average error is two point a half percentage points on the margin between the two candidates. But in 2016, it was a little over six points of error. That was by far our worst error. In 2018, we were off by 1% and a tenth of a percent. And in 2022 we were off by 2.2 points, right at our average. So going into this year, I'm certainly hopeful that we'll be close or under our average error. I certainly pray that we don't have a repeat of the 2016 large error and we've done what we know how to do to improve the methodology. And now we'll just see in November whether it really works out or not.

Marisa Wojcik:

Do you think that there is trust in polling?

Charles Franklin:

Oh, there's a lot of doubt about it. And that especially blew up after 2016. I couldn't count the number of press interviews I've given them on the topic of "Is polling broken?" or in their view, "Why is polling broken?" You know, as a political scientist and a methodologist, I think there are clear reasons to say it's not broken, but there are these elements of certain people who don't want to respond. In the past, they seemed like they were more random in their politics. Recently, it seems like that's a little more correlated with political party, and that is a real challenge to the polling industry. But I do think there's a little bit of an oddity to it that people — some people who complain about polling — simultaneously hold it up as if it should be much more perfect than it can reasonably be. So, you know, if you're thinking about is the poll accurate to half a percent of the election outcome, that's an unattainable standard. Is it getting the winner right? That's a lot better. And is it pretty close to that winner's margin or if we're talking about policy issues, is it giving us a good and reasonable representation about how people feel about policy issues? I think if you have a reasonable view of it, which is the margin of error in these polls is around 3 or 4% in most cases. Plus there are other factors that affect accuracy, like how you ask the questions and whatnot. I think we do tolerably well in being in that plus or minus four on most questions. And the thing that I think is most satisfying for me is when we see two different pollsters for different organizations with no connection asking a similar question and getting very similar results — that's truly independent polls of the same place at the same time — and they get the same answer within a little bit. So I do think there's plenty of reason as a technician to say, "Polling's doing OK." But I think the idea that polling, especially in 2016, was seen as so overwhelmingly showing Clinton winning that people had no expectation that Trump would win. And when that happened, the polls took much of the blame for being surprised so much. And I think rightly so, here in Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania, there were 134 polls in the fall of 2016. Only one of them in Michigan ever showed Trump ahead, and that was a couple of weeks before the election. And so we were all off. And that is a real problem for polling. So these changes that we've made since 2016 are trying to address what was the underlying reason why we were so systematically wrong in 2016. And as I say, I think it is, Trump reaches a set of voters and mobilizes them to vote, especially in 2016 that hadn't been mobilized before. The Clinton campaign maybe underperformed in voter mobilization, famously not coming to Wisconsin that year, for example. So there were multiple things going on, but the bottom line is we had a pretty brutal lesson out of 2016 that we've tried to respond to, but to hold us up to an impossible standard is too much. And to say, well, this is somewhat informative and maybe it's right — I think that's pretty good way to look at this, rather than take me to the decimal point and hold me to that decimal point.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us