AI is starting to affect elections and Wisconsin has yet to take action

Wisconsin lawmakers have not taken official steps to regulate use of artificial intelligence technology in campaigning, even as other states and Congress introduce and begin to implement guardrails.

Wisconsin Watch

August 9, 2023

A portion of a screenshot from an AI-generated PAC advertisement posted to Twitter on July 5, 2023 features an image of a candidate seeking to qualify for the Republican debate in Milwaukee on Aug. 23. (Credit: SOS America PAC / Twitter)

This article was first published by Wisconsin Watch.

Heading into the 2024 election, Wisconsin faces a new challenge state lawmakers here have so far failed to address: generative artificial intelligence.

AI can draft a fundraising email or campaign graphics in seconds, no writing or design skills required. Or, as the Republican National Committee showed in April, it can conjure lifelike videos of China invading Taiwan or migrants crossing the U.S. border made entirely of fictional AI-generated footage.

More recently, a Super PAC supporting a Republican presidential candidate’s bid to make the Milwaukee debate stage on Aug. 23 used an AI-generated video of that candidate to fundraise — which one campaign finance expert called an “innovative” way around campaign finance rules that would otherwise ban a Super PAC and candidate from coordinating on an ad.

Technology and election experts say AI’s applications will both “transform” and threaten elections across the United States. And Wisconsin, a gerrymandered battleground that previously weathered baseless claims of election fraud, may face an acute risk.

Yet Wisconsin lawmakers have not taken official steps to regulate use of the technology in campaigning, even as other states and Congress introduce and begin to implement guardrails.

Rep. Scott Krug, R-Nekoosa, chair of the Assembly Committee on Campaigns and Elections, told Wisconsin Watch he hasn’t “related (AI) too much to elections just yet.”

In the Senate’s Committee on Shared Revenue, Elections and Consumer Protection, “it just hasn’t come up yet,” said Sen. Jeff Smith, D-Brunswick.

Election committee members in both chambers expressed interest in possible remedies but doubt that they could pass protections before the 2024 election cycle.

Rep. Clinton Anderson, D-Beloit, is drafting a bill that would mandate disclosure of AI, sometimes called “synthetic media,” in political ads, something experts call a basic step lawmakers could take to regulate the technology.

Wisconsin Rep. Clinton Anderson, D-Beloit, is working on a bill modeled on a Washington law that would require disclosure of the use of artificial intelligence in campaign ads. (Credit :Drake White-Bergey / Wisconsin Watch)

“If we wait til 2024, it’s gonna be too late,” Anderson said in an interview. “If we can get this minimum thing done, then maybe we can have a conversation about, ‘What’s the next step?'”

“No matter where you fall politically, I think you should want some transparency in campaigns,” he added.

The Wisconsin Elections Commission declined to comment.

The AI threat: ‘Real creepy real fast’

Several lawmakers said AI repackages old problems in new technology, noting voters have encountered deceptive visuals and targeted advertising before.

But generative AI makes such content cheaper, easier and faster to produce. New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice notes that Russian-affiliated organizations spent more than $1 million a month in 2016 to produce manipulative political ads that could be created today with AI for a fraction of the cost.

Dietram Scheufele, who studies science communication and technology policy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said that while some of the doomsday predictions about AI are overblown, “we’re definitely entering a new world.”

The technology, he said, “gets real creepy real fast.”

Scheufele cited a prior study in which researchers morphed candidates’ faces with the participant’s own face in a way that remained undetectable to the participant. They found that people who were politically independent or weakly partisan were more likely to prefer the candidates whose faces had been — unbeknownst to them — morphed with their own.

“This was done a long time ago before the idea of actually doing all of this in real time became a reality,” Scheufele said. But today, “the threshold for producing this stuff is really, really low.””

Campaigns could micro-target constituents, crafting uniquely persuasive communications or advertisements by tailoring them to a person’s digital footprint or likeness. Darrell West, who studies technology at the nonpartisan Brookings Institution, calls this “precise message targeting,” writing AI will allow campaigns to better focus on “specific voting blocs with appeals that nudge them around particular policies and partisan opinions.”

AI will also quicken the pace of communications and responses, permitting politicians to “respond instantly to campaign developments,” West wrote. “AI can scan the internet, think about strategy, and come up with a hard-hitting appeal” in minutes, “without having to rely on highly paid consultants or expert videographers.”

And because AI technology is more accessible, it’s not just well-funded campaigns or interest groups that might deploy it in elections. Mekela Panditharatne, counsel for the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program, and Noah Giansiracusa, an assistant professor of mathematics and data science, described several ways outside actors might use the technology to deceive or influence voters.

Aside from using deepfakes to fabricate viral controversies, they could produce legions of social media posts about certain issues “to create the illusion of political agreement or the false impression of widespread belief in dishonest election narratives,” Panditharatne and Giansiracusa wrote. They could “deploy tailored chatbots to customize interactions based on voter characteristics.”

They could also use AI to target elections administrators, either through deluges of complaints from fake constituents or elaborate phishing schemes.

“There is plenty of past election disinformation in the training data underlying current generative AI tools to render them a potential ticking time bomb for future election disinformation,” Panditharatne and Giansiracusa wrote.

For Scheufele, one major concern is timing. It can take seconds for AI to create a deepfake; it can take days for reporters to debunk it. AI-driven disinformation deployed in the days before an election could sway voters in meaningful ways.

By the time people realized the content was fake, Scheufele said, “the election is over and we have absolutely no constitutional way of relitigating it.”

“This is like making the wrong call in the last minute of the Super Bowl and the Patriots win the Super Bowl, even though they shouldn’t have,” Scheufele said. “They’re still going to be Super Bowl champions on Monday even though we all know that the wrong call was made.”

Guardrails of democracy

In the abstract, every single aspect of AI is “totally manageable,” Scheufele said.

“The problem is we’re dealing with so much in such a short period of time because of how quickly that technology develops,” he said. “We simply don’t have the structures in place at the moment.”

But Wisconsin lawmakers could take initial steps toward boosting transparency.

In May, Washington state passed a law requiring a clear disclaimer about AI’s use in any political ad. Anderson’s team looked to Washington’s law as a model in drafting a Wisconsin bill.

Printed ads with manipulated images will need a disclosure “in letters at least as big as any other letters in the ad,” according to The Spokesman-Review. Manipulated audio must “have an easily understood, spoken warning at the beginning and end of the commercial.” For videos, a text disclosure “must appear for the duration” of the ad.

A similar bill addressing federal elections has been introduced in both chambers of Congress. A March 2020 proposal banning the distribution of deepfakes within 60 days of a federal election and creating criminal penalties went nowhere.

Krug called Washington’s law a “pretty interesting idea.”

“If (an ad is) artificially created, there has to be some sort of a disclaimer,” Krug said.

However, he indicated Republicans may wait to move legislation until after Speaker Robin Vos, R-Rochester, convenes a task force later this year on AI in government.

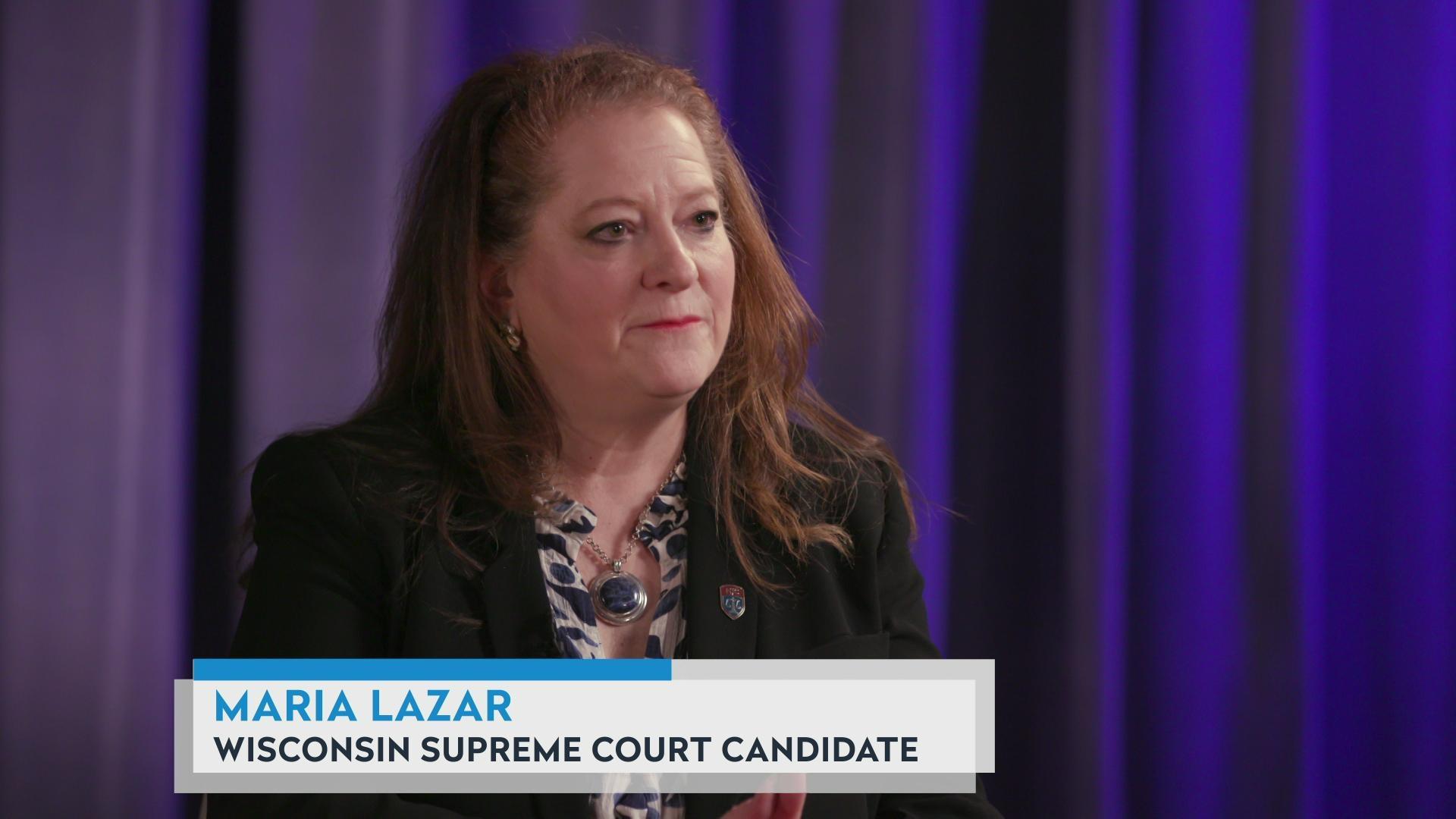

Rep. Scott Krug, R-Nekoosa, chair of the Assembly elections committee, is open to regulating the use of AI in elections, but legislation may not be ready in time for the 2024 election. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

Sen. Mark Spreitzer, D-Beloit, another elections committee member, noted Wisconsin law already prohibits knowingly making or publishing “a false representation pertaining to a candidate or referendum which is intended or tends to affect voting at an election.”

“I think you could read the plain language of that statute and say that a deepfake would violate it,” he said. “But obviously, whenever you have new technology, I think it’s worth coming back and making explicitly clear that an existing statute is intended to apply to that new technology.”

Just the beginning

Scheufele, Anderson, Spreitzer and Smith all said that Wisconsin should go beyond mandating disclosure of AI in ads.

“The biggest concern is disinformation coming from actors outside of the organized campaigns and political parties,” Spreitzer said. Official entities are easier to regulate, in part because the government already does.

Additional measures will require a robust global debate, Scheufele said. He likened the urgency of addressing AI to nuclear power.

“What we never did for nuclear energy is really have a broad public debate about: Should we go there? Should we actually develop nuclear weapons? Should we engage in that arms race?” he said. “For AI, we may still have that opportunity where we really get together and say, ‘Hey, what are the technologies that we’re willing to deploy, that we’re willing to actually make accessible?'”

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us