- Donate

- Watch

-

-

-

Explore Online

-

-

PBS

Passport

PassportSupport PBS Wisconsin and gain extended access to many of your favorite PBS shows & films.

-

- TV Schedule

- News

- Education

- Support Us

-

Greetings from the garden! I’m Sig, one of Let’s Grow Stuff’s green-ish thumb enthusiasts here at PBS Wisconsin. You might remember me from last year when I forged, unpracticed, into small space balcony gardening and shared what I learned — from planning, to planting to harvesting — on the Let’s Grow Stuff blog.

I’m back, baby (spinach), and this season I’m turning 180 degrees from the monkish solitude of me and my veggies to the engaged world of community gardening! I’m curious about the ways gardening brings people together — how a garden transforms from a private act of cultivation to a public, social or collective practice of place-making, stewardship and community care.

Throughout the growing season I’ll be visiting our friendly and talented Let’s Grow Stuff producers in their very own community garden plot located in Madison’s Eagle Heights Community Gardens. I’m excited to learn about the stuff they’re growing, their on-the-ground experience tending a plot at Eagle Heights, and meeting some of their gardening neighbors!

To prepare, however, I did a little homework. Having visited only a few community gardens in the past, I wanted a better understanding of their history in the United States, and I thought you might, too!

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Agricultural Library provides a basic definition:

Community gardens are collaborative projects on shared open spaces where participants share in the maintenance and products of the garden, including healthful and affordable fresh fruits and vegetables.

They’re found in urban, suburban and rural communities. They grow an array of crops, flowers and herbs, serve as insect and wildlife habitats, promote the growth of native plants, and engage in soil improvement by teaching about crop rotation and cover cropping.

While diverse in expression, community gardens share a social mission. At a minimum, this means people grow in community, either on neighboring individual plots on a piece of land, or by collectively growing and managing one larger plot together.

More ambitiously, many community gardens have social goals, like ensuring that people facing economic hardship have access to produce, teaching children about growing and gardening, nurturing intergenerational relationships, combating social isolation, preserving ethnic and cultural food or farming traditions, or countering urban abandonment and its persistence of food deserts.

Community gardens are located in neighborhoods, at schools, public libraries, hospitals, universities and many other sites. Sometimes, the garden land is owned or leased by a public municipality or state, sometimes by a group of private individuals, other times by a community group or non-profit association.

Researchers place one of the first examples of community gardening in the late 19th century, but for generations before this, across the Indigenous lands America occupies, members of our First Nations cultivated food, flowers and herbs in diverse communal forms. Today, as movements for Indigenous rights proliferate and gain visibility, we’re learning more about these ongoing practices.

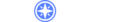

Amid America’s 1893-1897 economic depression, Detroit’s mayor, Hazen Pingree, devised a program to combat ballooning unemployment called Pingree’s Potato Patches. The city of Detroit temporarily donated 430 acres of land — mainly vacant lots — to over 900 families who were given a quarter to half an acre each, along with seeds to farm. Once their garden fed the family, they sold any surplus yield at market. Pingree’s patches were a financial success and a national model for garden-based poverty relief programs. They became a prototype for community gardening we see later in U.S. history as a top-down temporary emergency measure in response to a national economic crisis.

1896 map of Detroit plotting Mayor Pingree’s garden allotments for the poor and unemployed of the city. (Source: Hathi Trust, public domain)

(Source: Library of Congress)

1891 marked the founding of the first U.S. school garden in Boston, and the start of the national School Garden Movement of the Progressive Era that would thrive until the end of World War I. “Nature study,” a new educational pedagogy prioritizing experiential learning took hold, and school gardens were celebrated as a means to cultivate the economic and civic “character” of children. They attracted diverse financial support from local school boards, civic improvement societies, garden clubs and women’s associations.

The School Garden Movement reached its height when America entered World War I. Included in the war effort, the Bureau of Education promoted the U.S. School Garden Army, a program enlisting 1.5 million children to cultivate 20,000 acres of vacant land.

During both World Wars, the United States government promoted domestic gardening, or “Victory Gardening,” as a patriotic duty essential to the civilian war effort. In WWI, the U.S. was called to address widespread food scarcity in Europe, and promoted local civilian food production to preserve U.S. farming output for soldiers and civilians abroad.

In the Interwar period during the Great Depression, models of anti-poverty gardening re-emerged in three ways. First, local governments offered work-relief gardens to public welfare applicants — similar to Pingree’s Potato Patches. Second, subsistence backyard and community gardens proliferated as a means to combat economic food insecurity. Finally, industrial gardens arose in which corporations like International Harvester provided garden sites to workers to offset reduced hours and short-term layoffs.

With the advent of World War II, the promotion of civilian gardening — including community gardening — was holistic: as a boost to local food supply during a time of rationing, to promote exercise and a healthier diet, and as a distraction from worry about loved ones abroad.

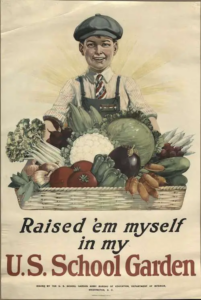

Community gardens, from the late 20th century through today, proliferate in response to a range of prolonged, intermittent, and/or enduring challenges that began in the 1970s with that decade’s staggering inflation, urban abandonment, and the dawn of the environmental movement.

A 1975 community garden on the Lower East Side of New York City. (Source: NYC Parks Department)

Local organizers, ordinary citizens, nonprofits and public institutions continue to launch and maintain community gardening programs as a way to create green space out of vacant lots, bring fresh produce to areas with no access to healthy food, stabilize neighborhoods, strengthen local food systems and mitigate — and adapt to — the climate crisis.

Wisconsin has growing (garden pun!) numbers and a wide diversity of community gardens, as does the greater Midwest. Which brings us back to the Let’s Grow Stuff community garden plot at Eagle Heights! Continue to follow along with me as I chat with our producer-gardeners, meet a few of the new and veteran growers who are their neighbors, and get a better sense of how all of them think about what “community” means to gardening!

In the meantime, take a look at some snapshots of what’s been happening in the Let’s Grow Stuff plot so far and we’ll see you soon!

What do you think?

I would love to get your thoughts, suggestions, and questions in the comments below. Thanks for sharing!

Sigrid Peterson