Reporting from the frontline as Wisconsin battled AIDS

Reporting on the AIDS pandemic by Carol Larson for Wisconsin Public Television in the 1980s provides a historical, local and personal window on LGBTQ+ health crisis reporting.

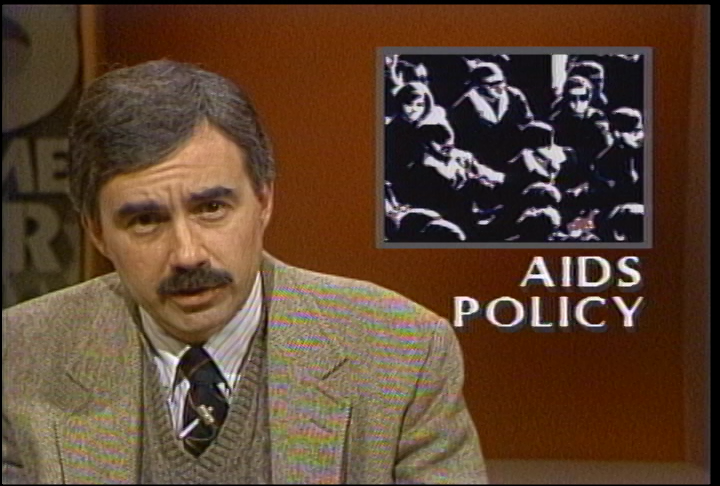

Wisconsin Magazine anchor Dave Iverson introducing one of reporter Carol Larson’s stories on AIDS from the 1980s

“Reporting on AIDS is a little bit like reporting on war. A grim listing of the latest statistics,” intoned Wisconsin Magazine anchor Dave Iverson introducing one of many packages on the deadly pandemic reported by Carol Larson for Wisconsin Public Television (now PBS Wisconsin) in the 1980s.

It wasn’t through the media that Larson first became aware of the virus but from her community connections. “Coming from an environment like the UW and having friends within the gay community, this was part of my social life,” Larson recalled. “Those friendships were maintained after I left school and started my career. And word kept on coming through, you know, there was stuff going on.”

What was going on was the slow, seemingly inevitable spread of AIDS. “People in Milwaukee and Madison in these fledgling AIDS support organizations saw what was happening on the coasts and really decided that that’s not going to happen here,” Larson said.

Blessed with time and recently passed gay rights legislation, Wisconsin’s response to the AIDS crisis was considered and comprehensive. Early into the pandemic, privacy and insurance coverage protections were established by law.

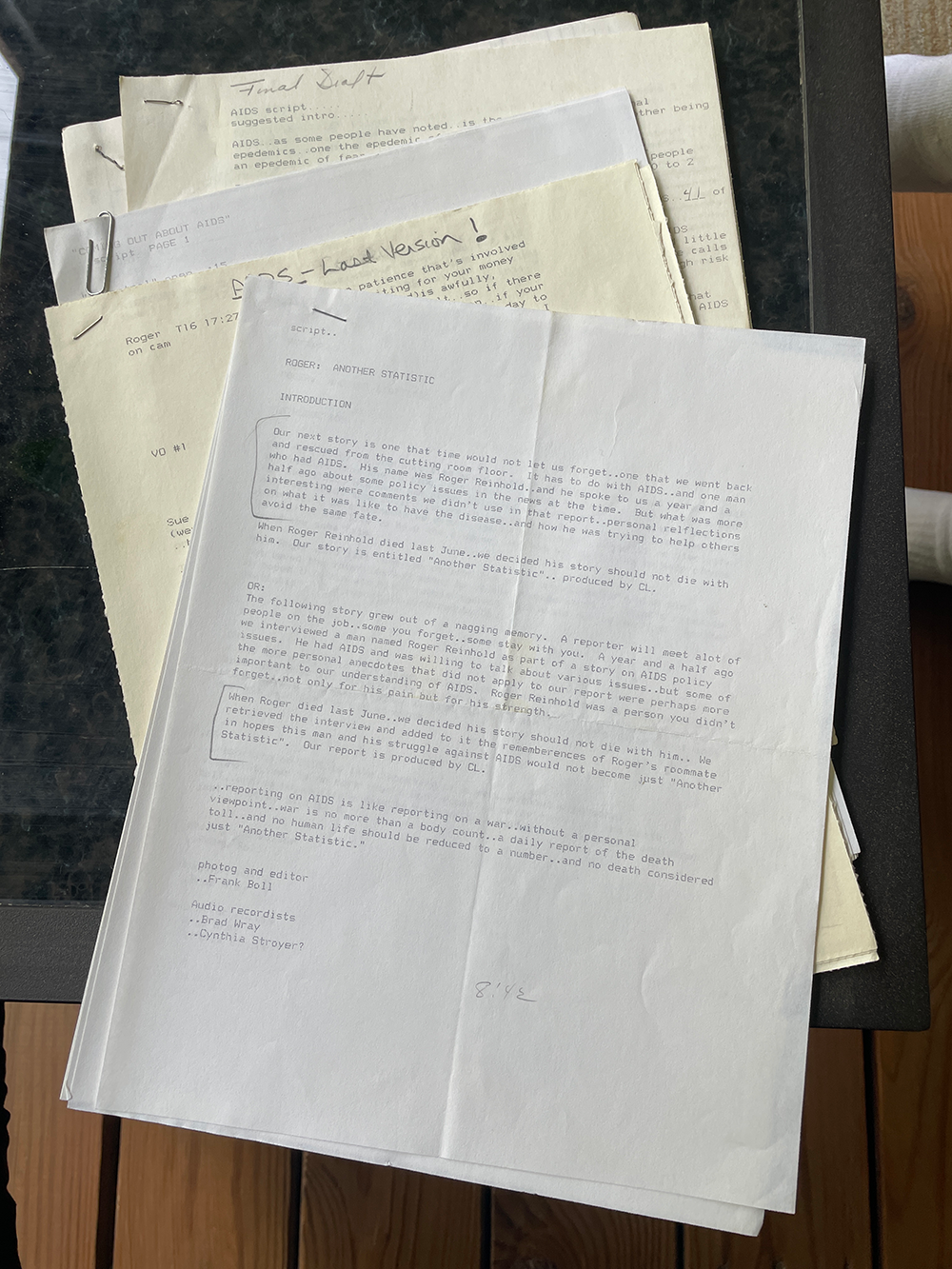

Larson’s saved scripts from her reporting on AIDS. She couldn’t part with the interview tapes that typically would be recycled.

But an informed public was also a vital part of the fight. “I would hear about these things and hear about the people who are being affected,” said Larson. “One of the biggest satisfactions of being in journalism in the first place is that you’re able to shine a light on something that’s not right. And hopefully somebody will do something about it. I mean, that’s a journalist’s link in the chain, the way you help make change”

Being that link required ongoing attention, and Larson had to advocate for continuing coverage of the crisis. “I’d come into a story meeting and say there’s a breakthrough or there’s a new aspect in the story. And I’d get groans and be told, ‘Oh my gosh, we already did that.’ Right. Yeah, but this is ongoing. This is developing,” she related.

What sticks most with Larson is the people she met and the courage they had to tell their story when AIDS came with a tremendous stigma. Meeting a man with HIV she would feature, Larry Bauman, who came to the station with a friend remains a vivid memory:

“I saw the receptionist pointing–because all of the conference rooms are glassed in–and pointing these two guys towards me, I went to open the door. And he thrust his hand out to me and I took it and I shook. He turned to the other guy, ‘I like her.’ Because that was a time when people were afraid to touch someone with AIDS. And he invited me over to his place after the segment was done. We just had a coffee. He gave me a big hug.”

Carol Larson, former Wisconsin Public Television reporter

Bauman would be among several people who succumbed to the disease that Larson got to know well and whose memories she hung on to.

“This was all videotape days and because of budgets we were supposed to recycle all those tapes after the piece was finished. But I could never bulk erase those interviews. They stayed under my desk in a box for a long time. One of my colleagues called it my ‘box of dead guys.’ But I just couldn’t do it.”

Larson is now retired, living in Madison, and at work on a historical novel set in Wisconsin during the era she was a reporter. Time has given her perspective on those days when shining a light on AIDS and the lives it affected motivated and moved her: “As a journalist, you know theoretically that you’re the first draft of history. But when you get older and you look back and you realize now it is history. History and the kind of reporting to be proud of.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us