Defrocked Priest’s Prison Bio a Window Into Gay Persecution

Historical records of the early 20th century reveal the story and voice of Father Andrew Jastroch, criminalized for his sexual orientation in a pre-Stonewall era.

Because historically homosexuality was against the law, much of the record of LGBTQ+ people in the closeted pre-Stonewall era comes from official records of police and court actions. Rarely do the people persecuted by these unjust laws have a voice.

An exception discovered during the deep research done by R. Richard Wagner for his book We’ve Been Here All Along is Father Andrew Jastroch. Were it not for Jastroch’s participation in a University of Wisconsin research study, only fragments of his life would be known, found in a few press reports and travel records. These include:

(Source: Milwaukee Journal)

On Easter Day in 1923, both the Milwaukee Journal and Milwaukee Sentinel publish short items with pictures of Father Andrew Jastroch. The assistant pastor of St. John Kanty had just joined the Navy as a chaplain. Jastroch is the son of immigrants and the Sentinel took note that he would be the only chaplain in service fluent in Polish.

It would seem to be a plum assignment, serving aboard Calvin Coolidge’s Presidential Yacht, The Mayflower. But within mere months, Jastroch would be hospitalized for unspecified reasons. Soon he would be discharged.

He next appears in the Boston Globe in attendance at the wedding of a famous Polish-American wrestler in his role as the pastor of a Polish Catholic church in Norwood, Massachusetts.

In 1930, Jastroch is part of a delegation from Washington, DC, of the Catholic Indian Service sent to Montana. The trip is to attend the diamond jubilee ceremonies at St. Ignatius Mission on the Flathead Indian Reservation. Newspaper headlines herald the 75 years since the coming of Christianity.

Shortly after, Jastroch embarks by ship to Hamburg and then to Poland for an extended stay with his sister who was a nun and Catholic school director.

It is unknown if Jastroch’s discharge from the military, frequent job changes and travel were related to problems from his sexual orientation being uncovered. But it is known to be the reason he ended up imprisoned at Waupun Correctional Institution in 1932.

His story is recorded in research by University of Wisconsin sociologist John Gillin. For his book The Wisconsin Prisoner: Studies in Criminogenesis, Gillin extensively interviewed Waupun inmates convicted of a variety of offenses. Jastroch appears anonymously in a chapter titled “The Making of the Sex Offender” under a sub-heading “Cases of Sodomy.”

Gillin was interested in questions of nature versus nurture, perhaps exploring if there is a genetic predisposition for crime or what environmental factors may have influence on criminal behavior. For each inmate his team also made a case study of a brother not in prison to draw comparisons. For Jastroch that meant his older brother John, a successful Milwaukee attorney from whom he had become estranged.

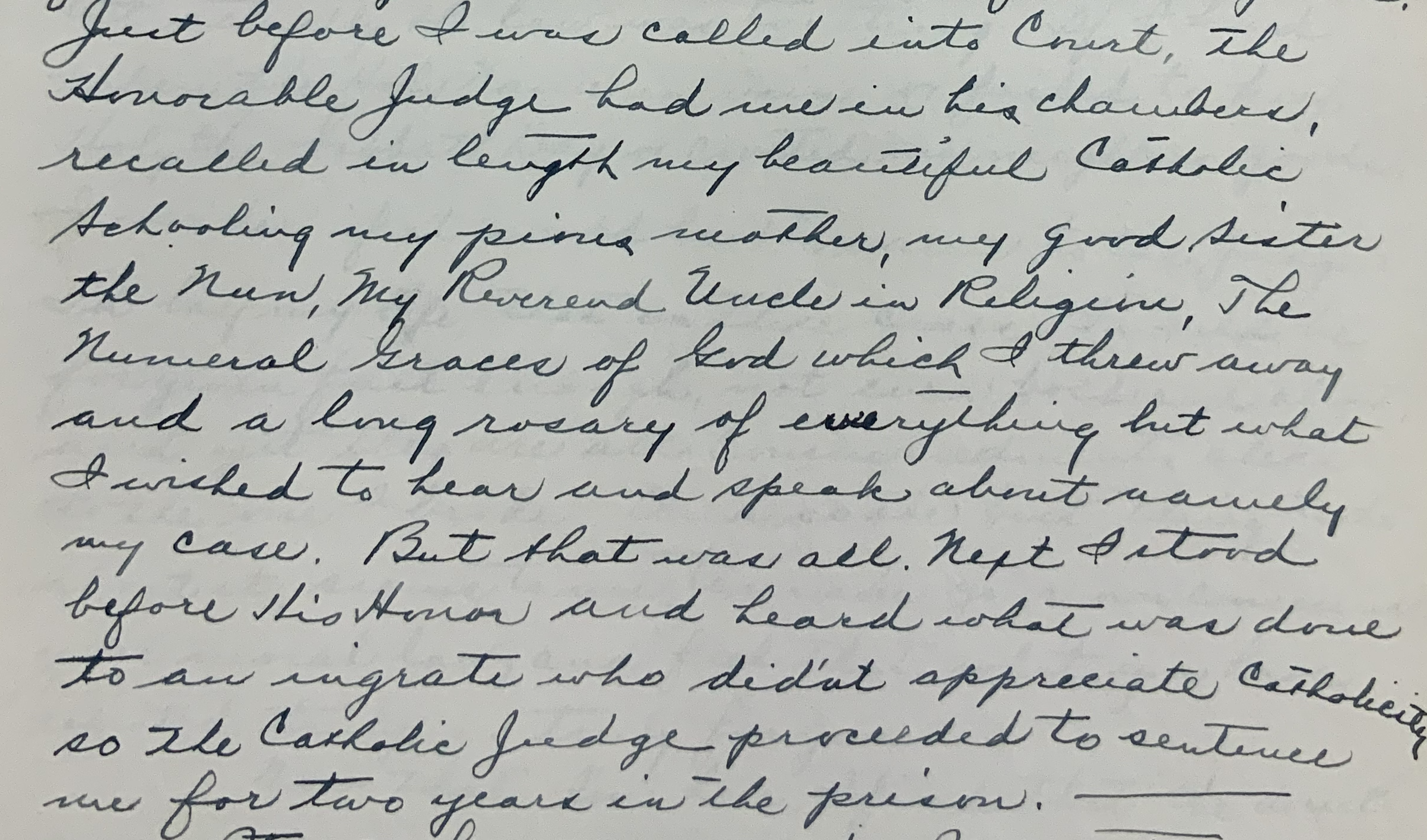

Gillin also asked his incarcerated informants to write their life stories, and in 23 handwritten pages Jastroch laid out a frank account of his growing up and discovery of his sexuality. He records his school age attractions to other boys and his first encounter in a cloak room as a college student at Villanova University in Pennsylvania. He writes of the impulses he held in check unless he was drinking, which became more frequent shortly before his arrest.

Recently returned from his travels to Europe and the East Coast, Jastroch indulges in a raucous night of drinking in what is euphemistically called a “Soft Drink Parlor” in winking compliance to prohibition era norms. He writes:

There were six of us in all my proprietor friend and his wife, another man and his would-be-wife, the bartender friend and I. We drank so much that I began to get sick and craved air. So the bartender friend “Joe” took me outside. There I threw out what I had in me, I remember my friend cleaning off my coat with a towel. When we got back, I was given a good stiff shot to brace me up. It certainly braced me. On an empty stomach I felt sick. Again the bartender friend very obligingly put me into his bed assisted by the proprietor’s wife. Pretty soon the bartender came in and it wasn’t long, we were getting acquainted with each other.

The drunken liaison was overheard and the next day it was reported to ”two drunkers who frequent (the) “Soft Drink Parlor” when not occupied as members of the Police Force.” Jastroch and his bartender partner were arrested. He did not call on his brother, nor any lawyer, when brought to court in Milwaukee for committing an illicit sex act with another man.

Many officials of the prison, among them the Sheriff himself wanted me to have my brother the attorney come to my assistance, but I would rather have died than drag him into this stinking affair. I was guilty and I wanted to be sentenced and gotten out of Milwaukee as soon as possible. I wanted then that the earth should open and swallow me up.

This proved an error, as his partner who did have representation received probation. Jastroch, seemingly having internalized the homophobia of his era, is also unfortunate in the assignment of the person to hear his case, a Judge O’Shaughnessy. The jurist had a higher standard for a man who had once held the priesthood.

Just before I was called into Court, the Honorable Judge had me in his chamber, recalled in length my beautiful Catholic Schooling, my pious mother, my good Sister the Nun, my Reverend Uncle in Religion, the Numeral Graces of God which I threw away and a long rosary of everything but what I wished to hear and speak about namely my case. But that was not all. Next I stood before his Honor and heard what was done to an ingrate who didn’t appreciated Catholicity so the Catholic Judge proceeded to sentence me to two years in the prison.

Despite his defrocking, and the pious pronouncements of Judge O’Shaughnessy, Andrew Jastroch would not lose his faith. He felt he had sinned, but questioned the severity of his punishment, writing “the law was too strong. If I had taken the Holy Name in vain, or failed to keep Holy the Sabbath Day or coveted my neighbors’ goods, I wonder if it would be the same to the Judge?”

Jastroch spent his time at Waupun reading in his cell, keeping his head down to avoid trouble, and bearing witness to a system he felt did nothing to reform and only to harden men. But he concludes affirmed in a simple faith taking to heart one of Jesus’s most simple messages:

I have learned here the valuable and only lesson of charity. I have learned here to hate wrong of every shape and manner, and I have also learned never to condemn anybody, because I could never qualify to throw the first stone, neither could any living man on God’s earth! (emphasis his)

When noted Milwaukee attorney John Jastroch died of a heart attack in 1938, his obituary made no mention of his youngest brother among his survivors. Andrew’s death three years later apparently went unnoticed. The only reference to it is in a registry of Naval Chaplains published in 1958.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us