Announcer: PBS Wisconsin Education leverages the power of public media to spark curiosity and ignite learning in Pre-K settings through 12th grade. Educational media can help build skills that students need to be successful. PBS KIDS content and activities enhance school readiness and support children to reach their full potential in school and in life.

We also deliver award-winning educational media for elementary through high school classrooms. Our media is aligned to state standards, and our locally-produced content is designed for and with Wisconsin educators.

We offer powerful and practical professional learning to support educators in activating all PBS resources, and we empower students to make their own media through our youth media initiative. Be part of our service by sharing with an educator you know today! Pbswisconsineducation.org.

[drumming]

Jessica House – Lady Thunderhawks Basketball

Jessica House: I started playing ball when I was eight years old. I just had a really good passion to play basketball for Oneida Nation. Basketball is my life, and so is the culture. My name is Jessica House. I am a senior, and I play for the Lady Thunderhawks.

To be a Lady Thunderhawk, you have to learn discipline. I mean, you’re role models. You’ve got to think about how you’re acting out in public.

[singing and drumming]

In order to play basketball at Oneida, you have to be in the culture. You have to participate. Not a lot of girls were raised into it, where I was. But they are starting to find their ways now. And some of them even come to Long House now.

[singing and drumming]

It’s important because I think it helps know who they really are. ‘Cause sometimes you get so caught up in the other world.

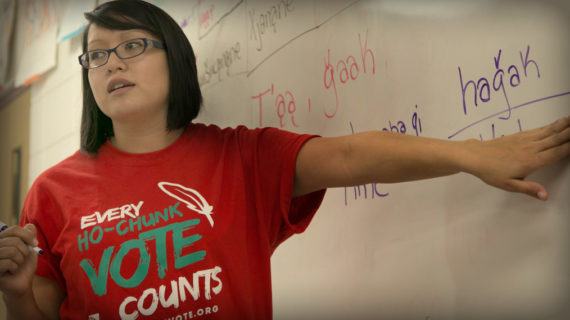

There’s other girls, like me and Tasha, we take separate classes out of school for an actual language class. Our teacher, Shalihkt, when he was younger, there was more of the elders around that spoke the language, whereas now we don’t really hear it.

Speaker: [speaking Oneida] Have you learned, have you learned it?

Jessica House: Shalihkt teaches us words to say. Every time we go in for a huddle, we go:

Group: [speaking Oneida] Whoo!

[“Native Puppy Love” by A Tribe Called Red]

[all cheering] Yay!

Jessica House: We have 11 girls on this Lady T-hawk team. I am captain. I’m also the point guard, so I’m expected to keep the game going, keep everyone under control. Keep myself under control!

Before, we had hardly any people in the stands. My sophomore year, the fans started to fill in. My parents only missed one game out of the three years I’ve been at Oneida. I think it’s really cool when all the parents are there supporting their daughters. It gives us our energy.

I don’t know how the other girls see it, but there’s no better feeling than when you play basketball.

Waadookodaading – Ojibwe Immersion School

Group: [speaking Ojibwemowin]

[“Prayer Loop Song” by Supaman]

Keller Paap: We knew that the number of existing elders who spoke Ojibwe fluently who were raised with Ojibwe as a first language were vastly diminishing. So, we knew we had to do something quick. And so that’s why we started “Waadookodaading.”

[speaking Ojibwemowin]

Brooke Ammann: Waadookodaading: It’s a place where our language lives; where the Ojibwe language lives.

Speaker: [speaking Ojibwemowin]

[“Prayer Loop Song” by Supaman]

Brooke Ammann: Language– I think with any cultural practice, it has a specific vocabulary and teachings that are associated with each activity in that practice. So, for instance, all the words about boiling sap, the way that it boils, have specific terms that describe it very, very accurately that allow you to develop a deep comprehension of the activity and why you do it and how you do it.

Speaker: [speaking Ojibwemowin]

[children singing in Ojibwemowin]

Keller Paap: I always say it’s an educational experience for students, but it’s a community movement. We’re facing some really unique challenges right now.

Brooke Ammann: We have a lot of statistics that are against us. We have a lot of issues with abuse and suicide, that show us as not being the most healthy of communities. And I always think of it, not just in terms of our culture surviving, but, really, our people surviving.

Speaker: [speaking Ojibwemowin]

Brooke Ammann: I didn’t learn to speak Ojibwe as a child, but when I started studying it as an adult in college, I quickly realized how much knowledge and capacity there is in a language to know who you are, where you come from, how to see the world in that unique way.

Speaker: [speaking Ojibwemowin]

Keller Paap: It’s certainly academically rigorous. It’s not just a culture program. It’s not just a language program.

[speaking Ojibwemowin]

Speaker: Miigwech.

Keller Paap: Ultimately, it’s prepping them and building an intellectual framework that they’ll be able to apply to and adapt to. No matter where they are in the world, that will help them. And I think they’re prepared with knowledge and ability that they feel proud of, that they feel connected to their ancestry in a deeper way. They have a much broader and deeper understanding of Ojibwe perspective in relation to the local community, the local environment, and the world.

[children singing in Ojibwemowin]

Ron Corn – Menominee Language Preservation

Ron Corn: I first go around and plow my relatives out, a couple aunties and cousins. Then I have my, I call them brothers, you know. That’s the way we say it in our language. Nematok, our friends, you know, close friends. We do things in a good mind and a good heart and a good way. And when we need that help, I guess we believe it’ll come to us too.

What I’m doing is ensuring that the language goes a generation beyond myself. And I’m gonna do that through my kids, you know.

Speaker: [speaking Menominee]

Ron Corn: I’m teaching Mimikwaeh the language using natural immersion. Natural immersion is you just talk about your day the way you would anything else, yeah, so, only it’s being done in Menominee. I decided to stay home and teach her the language, ’cause it’s my last unique opportunity to be able to raise a First Language fluent speaker.

I think it’s hard for her to want to speak because nobody else does, you know. There’s probably about eight people that speak it. We’ll call it 10, you know? She’s got 10 of 10,000, you know? What’s that percent? .0001, .0001%. And so that’s a reality check. The language, it could die. The idea that we’re trying to preserve is a living language. Pematesemakat, it lives.

[chanting in Menominee]

Every little thing is gonna be all right

For me and you

Don’t you worry about a thing

Every little thing is gonna be all right

[chanting in Menominee]

[speaking Menominee]

Ron Corn: So there’s words readily available for everything in nature. The word for falling snow is paeqnan. The word for snow on the ground is kon. Crusted snow, wanaew, you know, we say wanaew. And the word snowflake is even different yet than both of them, we say pewaeqsew.

[conversing in Menominee]

Ron Corn: The beautiful thing is it’s not much easier in the woods, you know, because our language is really based on what’s going on out there. But how do we make that transition into today’s life too, you know? Because we’re not always sugaring, we’re not always ricing. We spend a lot of days at home, in the office, on the road. And we gotta learn to express those things too, you know. The language has to make that transition if it’s gonna be relevant and if it’s gonna survive, you know.

When I was young, my first main teacher, Waqseciwan, she was starting to get sick and forgetful, you know. One day we were just sitting at her house, talking, and she tells me, “Now I can die,” she told me. “For 25 years,” she said, “I’ve tried to teach someone this language. Now, today, I’ve done that.”

Then she continued on in Menominee, you know, she said, [quoting in Menominee]

She told me. She says, “You know, maybe you’re gonna be an old man,” she says, “and hear these kids talking our language.” She said, “I love ya. Don’t give up.”

[singing softly]

Dylan Jennings – Powwow Culture

Dylan Jennings: Sometimes, it gets hard to balance these two worlds. There’s different responsibilities that I hold at school. There’s different responsibilities that I hold for the Powwow Trail. I’m a junior at UW-Madison. I come from the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe.

[“Electric Pow Wow Drum” by A Tribe Called Red]

[vocable singing]

Announcer: All right, don’t go away gentlemen.

Dylan Jennings: A powwow is a social gathering. This is like our way of bringing our whole Native community together.

Announcer: Okay, I believe we are ready for our first round entry. So we are gonna ask those of you that are able to please rise, remove the covers off your head, to pay respects not only just to our Stars and Stripes, but to the original flag of this continent, our Eagle Staffs.

Dylan Jennings: The veterans play a huge role because they went to battle for us. They went to battle for our people, and they always have.

Powwows are used as a means to educate people. That’s why they’re so open to the public and everything. A lot of people classify Native Americans as, you know, “Oh, they’re all Indians.” Well, no, you know. We’re all from different nations that are all really, really different. We all have different languages. We all have different ways of life. And we’re completely different. Just from being on the Powwow Trail, you get to learn so much about different Native nations.

When I was just a little guy, you know, I’d watch those men’s traditional dancers, and they always had a big impression on me, you know? And I always saw them as, you know, almost like the protectors of the powwow.

[vocable singing]

It’s almost like I’m hunting, especially when you do the sneak up. You’re out there looking for you prey or for your Waawaashkeshi, we call it. That’s our word for deer.

I started singing with Midnite Express a few years ago. Those people on that drum are my family.

[vocable singing]

Sometimes, like when it’s not a contest song, I’ll get to look out there and see all those feathers out there, moving and bobbing with the beat, and people just jamming out, and that’s a great feeling.

[drumming and vocable singing]

[“Electric Pow Wow Drum” by A Tribe Called Red]

When you’re dancing, you’re dancing for the ones that can’t dance anymore. That’s what they say. You dance hard so the ones that are watching that can’t dance or the ones that aren’t able to make it to the powwow can feel those feelings from here.

I really try to encourage younger– I call them little brothers on the Powwow Trail. That’s another reason I dance and sing, is to help motivate these young ones to carry on our traditions.

I really feel that I was put here on this earth to help pass things on. I want to see these traditions, these ways, passed down ’til I’m gone, and on.

Tall Paul – “Prayers in a Song”

[engine starts]

[Tall Paul performing “Prayers in a Song”]

[rapping]

I feel the latent effects of assimilation Inner city Native raised by bright lights Skyscrapers Born with dim prospects Little peace in living as a child, hot headed About the fact I wasn’t wild Like they called my ancestors Imagined what it’d be To live nomadic off the land And free Instead I was full of heat Like a furnace ’cause I wasn’t furnished With language and traditional ways of my peeps Yeah, I used to feel like I wasn’t truly Indigenous Now I say Miigwech gichi-manidoo For showing me my true roots Definitely Native Take responsibility for being educated My people and customs Originating from early phases of history It’s deeper than frybread and contest powwows Tears shed in the sweat lodge Prayers go out to all those I’ve wronged And who have wronged me Gotta treat ’em like family Gichi-manido wiidookawishin Ji-mashkawiziyaan Mii dash bami’idiziyaan Miizhishinaam zaagi’iiwewin Ganoozh ishinaam Bizindaw ishinaam Mii-wenji nagamoyaan Nimishomis wiidookawishinaam Ji-aabajitooyaang anishinaabe izhitwaawin Mii-ji-bi-gikendamaan Keyaa anishinaabe bimaadiziwin Becoming aware of a heartbeat’s Fragility so I pray For my creator’s will and humility It seems my prayer’s weak I can’t speak Not a linguist Does he hear my English when I vent I fear the answer to the question This is symbolic of anguish I feel regarding language And the obligation of revitalizing Something sacred Failure to carry through is disgracing a nation My first tongue’s in need of a face lift But deciphering conjugations Like trying to find my way through a maze in the matrix Complex hard to start without an end Aside from being fluent I gotta push the limit If I’m gonna keep pursuing So I use it in a way that Relates to my life and vocab Bring some entertainment to it Spit it on a track And I take it out the class Can’t let what I lack Become a self-defeating habit That’ll make me want to quit Gichi-manido wiidookawishin Ji-mashkawiziyaan Mii dash bami’idiziyaan Miizhishinaam zaagi’iiwewin Ganoozh ishinaam Bizindaw ishinaam Mii-wenji nagamoyaan Nimishomis wiidookawishinaam Ji-aabajitooyaang anishinaabe izhitwaawin Mii-ji-bi-gikendamaan Keyaa anishinaabe bimaadiziwin It’s far fetched but grandfather Please help me learn it Help me assist in keeping it From burning, don’t let me quit And flee from working For a worthy purpose Enlighten me and help me Comprehend effects of my service I need a spark in my desire From something higher Prior to negative reminders Killing my stride Sometimes I’m the type that Likes getting results overnight Without sweating or stressing overnight So I pray, creator, give me strength Then I can move on Creator show us love So it can spread around Communicate with us from above Hear me now, my prayers in a song I speak ’em out loud Grandfather help us To revitalize the language And ways so we walk the red road That you paved Communicate with us from above hear me now My prayers in a song I speak ’em out loud

[fading beat]

Pat and Chris Peterson – Treaty Fishing Rights

Pat Peterson: I think it was 1984. I can’t remember exactly. We just came over here because the treaties were reaffirmed, and it opened the waters to come down to the Keweenaw Bay area.

I run Peterson’s Fish Market and 4 Suns Fish & Chips take-out. I oversee everything, but I can do everything. I can prep, I can filet. I can make nets, I can mend nets. I can do book work.

We’re from the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

When we got here, there was lots of prejudice around here. They did not want us down here fishing. They thought these fishing grounds belonged just exclusively to them. The cable man would come into the homes to hook up the cable and he’d say, “You guys don’t belong here. You’d better go back to Wisconsin.”

In school, they were telling the younger kids that those Wisconsin Indians don’t belong here and they should go back home. They have no right to be here. In school, even.

They don’t understand about treaty fishing, you know, what we gave up for our rights to continue doing this today. All the land they’re on was ours. So in exchange for shoving us off our land, putting us on these reservations, we get to hunt and fish and gather rice as long as the sun rises and sets. Well, that’s forever.

All the boys started working on the fish boats when they were about 12. It’s a family tradition for the Petersons. Our oldest son, Chris, he runs our fish boat.

Chris Peterson: Actually, I like to call myself the head of acquisitions. Whitefish is our prime target. Any trout we get is incidental. It’s always a hunt, east, west north, south, in shallow or out deeper. You know, it’s always a constant hunt. And so I’ve been lucky enough to be able to find some really good patches of fish. You know, you have to read what the nets are telling you.

Let’s get as much fish as we can, reset our gear, get back to the shop. And hopefully they’re not completely out of fish, so. We have a lot of people that depend on a lot of fish. I know if I don’t catch enough, everybody suffers. Not just the extended family, but all the employees. I’m real proud that we provide so many jobs for the area. You know, when people are getting laid off left and right, we’re still adding jobs.

Pat Peterson: This December, it’ll be 20 years that we’ve been in operation. So it’s just been growing. You know, lots of long hours, lots of hard work. All the people that were against us are now customers. The cable man came in one day and I said, “We made it.” Here he comes, buying our fish, [laughing] so.

[slow electric guitar outro]

Announcer: PBS Wisconsin Education leverages the power of public media to spark curiosity and ignite learning in pre-K settings through 12th grade. PBS KIDS content and activities enhance school readiness and support children to reach their full potential in school and in life. Our award-winning educational media for elementary through high school is aligned to state standards, and our locally-produced content is designed for and with Wisconsin educators. Pbswisconsineducation.org.

Search Episodes

Related Stories from PBS Wisconsin's Blog

Donate to sign up. Activate and sign in to Passport. It's that easy to help PBS Wisconsin serve your community through media that educates, inspires, and entertains.

Make your membership gift today

Only for new users: Activate Passport using your code or email address

Already a member?

Look up my account

Need some help? Go to FAQ or visit PBS Passport Help

Need help accessing PBS Wisconsin anywhere?

Online Access | Platform & Device Access | Cable or Satellite Access | Over-The-Air Access

Visit Access Guide

Need help accessing PBS Wisconsin anywhere?

Visit Our

Live TV Access Guide

Online AccessPlatform & Device Access

Cable or Satellite Access

Over-The-Air Access

Visit Access Guide

Passport

Passport

Follow Us