Georgia Brown: Just ’cause you can see it and it says it, doesn’t necessarily mean it’s true. You have to think about who made it, why they made it, who did they make it for, and who’s getting left out of the map. Those are very important to unpack when you’re looking at a map.

[upbeat music]

Sergio Gonzalez: [thinking] All right, so if I go left, I should get here, but then I have to turn around… the sticks? That doesn’t make any sense. I don’t understand, this is frustrating. Uh, no, is it this way, or is it right? So go ahead and go back around, do-si-do. I think it’s jump twice over the– Oh, hey, Cat!

Cat Phan: Hey, Sergio.

Sergio: So sorry. I’m trying to find the library. I got this map. I think it’s supposed to be able to get me there.

Cat: Let’s see if I can help. [slide whistle] Mm, I don’t think this is gonna help you.

Sergio: Uh, but it’s a map. This should tell me exactly where I have to go.

Cat: Uh, I think we need to learn a little bit more about maps. C’mon, let’s go.

Sergio: Okay.

Georgia: My name’s Georgia Brown, and I’m the public services librarian here at the American Geographical Society Library. We’re actually the second-biggest map and geography library in the United States. Yeah, right here in Milwaukee.

Sergio: Georgia, how many maps do you guys have in here?

Georgia: It’s not an exact count, but 635,000 is the closest count we have.

Cat: That’s a lot of maps.

Georgia: Yes, it is a lot of maps. And we’re also unique in that we’re both a historical and a contemporary map collection. So our oldest thing is from 1452, and our newest stuff’s gonna be from 2025.

Cat: How do you define a map?

Georgia: I call a map a visual representation of a space. That’s a super broad definition, and a lot of people might have other, like, taglines that they wanna put into that, but that is the simplest way to define a map. A visual representation of a space.

Sergio: How long have people been using maps for?

Georgia: I think the oldest one that people have ever found is a Babylonian tablet.

Sergio: Hm.

Georgia: So pretty much as long as we know about history, people have been using maps.

Sergio: People have been making maps for thousands of years. This clay tablet from ancient Babylon, an area in modern-day Iraq, is from around 600 BCE, over 2,500 years ago! It may not look like much to us, but it features a simple representation of how its creators understood their world. What are the ways in which we know that this is a map? What are the, kind of the pieces that bring a map together?

Georgia: Sure thing. So when I teach students, I tell them four things. Maps will almost always have a title, a scale, a legend or key, and a compass rose, which shows which direction north is. And it’s not always as standard with these older maps, but you can see they’re starting to do it.

Cat: So what are we looking at here? You’ve pulled some maps for us to look at.

Georgia: I pulled some early Wisconsin stuff. So these maps go from about, I think the earliest one is 1600s, and then they go to as late as 1836. It’s not all of Wisconsin. Like I said, not on purpose. Unlike this one, where Wisconsin is right now, it’s called the Northwest Territory. And a couple other things don’t actually label it as Wisconsin.

Cat: How do you read a map? Some of these maps are so different.

Georgia: No one’s ever asked me how to read a map before, so good job asking me a first question.

Cat: Yay!

Georgia: I always give someone a gold star when they do that. For me, personally, I will find the identifying feature that I can find easiest. So for Wisconsin, it’s almost always Lake Michigan. So we start there. Even though this is in Italian, like, “Lago Michigan,” sure. It’s Lake Michigan. And then obviously, like, the rest of the

state isn’t as well-labeled or anything else, but you can kinda keep going. So, like, this is really close to Milwaukee in the spelling. Just close enough that I’m like, “Maybe that’s it.” So that’s the best way I know how to do it, especially with these early maps of Wisconsin ’cause they’re not labeled with the way we spell things now or the rivers that we know about. All right, so I gave you all a copy of my favorite teaching map, which is right here. And it is Coronelli’s map of the Great Lakes from 1687, and it’s my favorite teaching map. So if you look at the Great Lakes, what do you see?

Sergio: I mean, the first thing I look at is, there’s just a bunch of different names in the lakes.

Georgia: Right, so Coronelli must have heard conflicting reports about what they were gonna call each of the Great Lakes. So instead of decide for everybody, he just writes in for Lake Michigan, “Lake Illinois,” “Lake Michigami,” or “Lake Dauphin” and lets the people decide later on. And then another reason it’s my favorite, is if you’ll look in the top right, the scale, it actually has, like, the French scale, the British scale, the Italian scale. So all of the miles are different ’cause they’re not standardized yet. They’re all, everybody has a different mile. And so, it’s kind of interesting that he includes all of them. Again, he’s, like, not deciding for anybody. He’s like, “This could, anybody could look at this map and be able to navigate around here.”

Cat: One of the great conveniences of maps is their size. You can have maps of all different sizes. A map’s scale is the indication of how distances on the map relate to distances in the real world. There are a few different ways to do this. A representative fraction shows the scale as a ratio. The first number, the numerator, is always 1. The second number, the denominator, is how much greater the real-world distance is. So if the scale is 1:100, it means one unit of distance on the map equals 100 units of distance in the real world. That distance unit can be anything. Centimeters, feet, miles, whatever! It holds true no matter what unit you’re using.

Sergio: Another option is to use a graphic scale. These are bars that show distances on the map itself. The maps we looked at here have scale bars. They show how many miles are represented by the measured lines. This one even has the different miles used by different countries at the time, since this was before measurements were standardized. Another way a map might show scale is simply in writing. A map might say “1 inch represents 1 kilometer,” or something like that. Whatever method is used, scale is crucial for using a map to navigate.

Cat: Right, so what can these maps tell us about Wisconsin?

Georgia: Hmm, that’s a great question. Kind of like what the path of the European explorers was. That you can see, like, the shape of Lake Michigan gets better. So if we start with this one that you’re looking at, they do a terrible job with what Green Bay looks like and how the shape of Lake Michigan actually, like, looks with the state of Wisconsin as we know it now. So as time goes on, they get better at actually mapping the lake. Sometimes, the people that actually went to Wisconsin made the maps, but a lot of times, it was just European map makers. They were writing with people who had actually been to Wisconsin, or reading books about people who had traveled to Wisconsin. So they’re using, like, just kind of, like, word of mouth.

Sergio: So you’re telling me that people would have to depend on the ideas of somebody who maybe had never been to this area?

Georgia: Yes, most of the maps in, like, the early, like, before the 1800s were made by people who had never been there before.

Sergio: Oh, my gosh.

Georgia: Yeah.

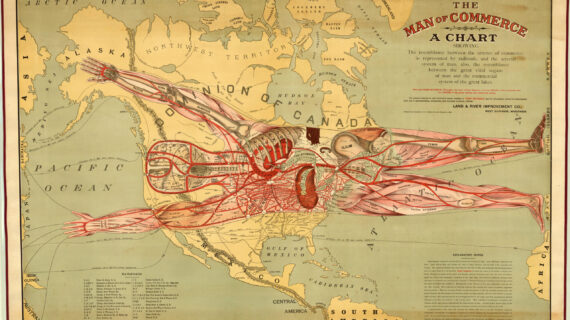

Sergio: By the early modern period in Europe, there was a big increase in the production of maps explicitly made for the purposes of navigation. Now, in the areas around the Great Lakes, which includes what is now Wisconsin, the growing North American fur trade was a big reason for traveling to and exploring the region. This trade involved the exchange of goods between different cultures. Europeans brought items like metal goods and textiles and traded with Native partners for animal furs and skins. Another big driver of charting this region during the 1700s was the effort to find a Northwest Passage. This was the hypothetical route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean via a water passage above North America. European explorers had no way of knowing if this was even really a possibility, but that didn’t stop many of them from trying to find it. In reality, the presence of sea ice and dangerous waters made this route impractical, if not outright impossible at the time. But the efforts to find such a route contributed to the mapping of the northern part of the continent. How can we read maps as ways of understanding the past? Because you might think of, it’s just a picture of a specific moment, but it’s probably telling us something about a different time period as well.

Georgia: Sure thing. I think maps are definitely, like, a nice little snapshot into, not necessarily the time, like a picture. That’s the exact moment that something’s happening. But it takes a long time to do this. So just to see the different place

names and what people thought was significant. Like, I don’t think that there’s any mountains between Milwaukee and Chicago. And that’s what, they’re showing a mountain range right here. So fun ideas about exploration. And sometimes, map makers really just didn’t like blank spaces on maps. So they’d put a fun little illustration or shade something in to make it so that they were, like, not doing just blank maps.

Sergio: So, tell me a little bit about why these different countries and different groups of people would wanna make a map and perhaps put themselves squarely at the center of it?

Georgia: Maps are a great way and a very quick way to try to be like, “This is actually my land.” So if you, you know, are erasing people that already live there, like the Native Americans, you could just be, like, “This map is all in French. We’ve got all French place names.” So, and they’re not saying anybody else lives here, so they’re just like, “This is the French.” That map is definitely a French declaration of ownership of the Great Lakes area.

Sergio: So what I’m understanding is when we read these maps, we should be careful not to think that they fully represent who was alive or present at these particular times.

Georgia: Yes, for sure. Just ’cause you can see it and it says it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s true. You have to think about who made it, why they made it, who did they make it for, and who’s getting left out of the map. Those are very important to unpack when you’re looking at a map. [television static]

Cat: I hope Sergio found his way home. Maps are about so much more than finding your way around. They can also be great primary sources for historical inquiry. They tell us lots of things about how the people who made and used them viewed a particular area, country, or even the whole world. Like all primary sources, we need to examine maps carefully and remember that no one source can ever tell the full story of a place. Looking closely and talking to an expert are great ways to get started using maps for historical research. Have you ever tried making a map? See if you can draw a simple map of a place you know well. It could be your neighborhood, your street, or even just your home or a single room. When you’re done, share your map with friends and see if they can recognize what you included and what you left out. It’s a great way to connect to a tradition that goes back thousands of years.

Sergio: Hey, Cat? I think I need your help. Yeah, I’m still pretty lost. Hmm.

[map tearing]

[playful music]

Search Episodes

Related Stories from PBS Wisconsin's Blog

Donate to sign up. Activate and sign in to Passport. It's that easy to help PBS Wisconsin serve your community through media that educates, inspires, and entertains.

Make your membership gift today

Only for new users: Activate Passport using your code or email address

Already a member?

Look up my account

Need some help? Go to FAQ or visit PBS Passport Help

Need help accessing PBS Wisconsin anywhere?

Online Access | Platform & Device Access | Cable or Satellite Access | Over-The-Air Access

Visit Access Guide

Need help accessing PBS Wisconsin anywhere?

Visit Our

Live TV Access Guide

Online AccessPlatform & Device Access

Cable or Satellite Access

Over-The-Air Access

Visit Access Guide

Passport

Passport

Follow Us