Wisconsin's 'point in time' count struggles to capture the state's homeless population

Homelessness has been increasing statewide according to the annual PIT count that's conducted by volunteers, but these counts struggle to accurately capture homeless populations around Wisconsin, especially in its more rural areas.

Wisconsin Watch

February 18, 2025

Sandy Hahn, housing manager at Community Action Coalition for South Central Wisconsin, fills out a survey documenting her interaction with someone sleeping in a car during the annual "point in time" count on Jan. 22, 2025, in the parking lot behind the Pine Cone Travel Plaza in Johnson Creek. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

This story was produced and originally published by Wisconsin Watch, a nonprofit, nonpartisan newsroom.

Just before midnight, with a fresh layer of snow sticking to the ground, volunteers Sandy Hahn and Britanie Peaslee slowly drive through Jefferson County’s local parking lots, gas stations, truck stops, parks, trails and laundromats, keeping their eyes peeled.

They’re grateful for the snowfall, which makes it easier to see footprints, fogged windows and occupied vehicles. They have a long night ahead of them, and being in a rural area makes their job — finding those without shelter — even more challenging.

“It’s a little bit easier when it is colder because you can see, OK this windshield is frosted from the inside, somebody’s been breathing in there for quite a while,” Peaslee said.

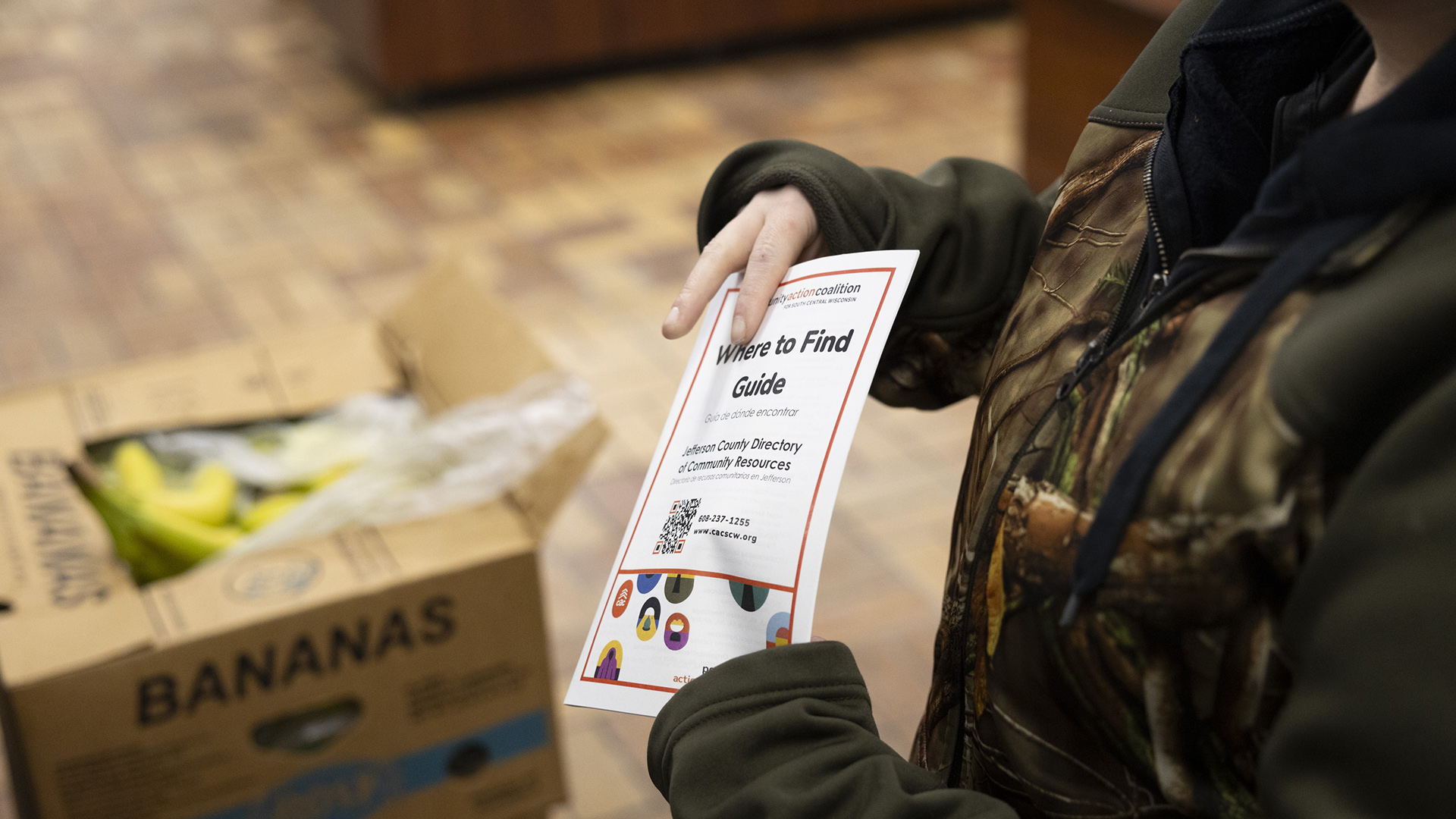

In Johnson Creek, they find most of the homeless living in cars parked behind the Pine Cone Travel Plaza — a local restaurant, gas station and truck stop. The duo carefully approach each vehicle — one with a sleeping child in the back — with blankets and a four-page questionnaire.

But that’s assuming the unhoused are willing to engage with the strangers at all, let alone at 3 a.m. while it’s 7 degrees and snowing outside.

- Britanie Peaslee, community resource liaison at Rainbow Community Care, left, and Sandy Hahn, housing manager at Community Action Coalition for South Central Wisconsin, prepare to begin the annual PIT count on Jan. 22, 2025, at a Kwik Trip in Lake Mills. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

- Sandy Hahn asks a Kwik Trip employee to hand out a stack of resource guides at a Kwik Trip in Johnson Creek in southeastern Wisconsin. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Jan. 22 marked Hahn and Peaslee’s fifth time participating in the annual “point in time” (PIT) count — a one-night snapshot of the number of people experiencing homelessness across the United States, including Wisconsin. The pair were among the eight volunteers conducting the counts in Jefferson County, a number Hahn considered to be low. Being in a small, rural area, they struggle to recruit volunteers.

This one-night snapshot — first conducted in 2005 — is the only required count of all people experiencing homelessness each year in the United States. The volunteers must follow strict guidelines set by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Peaslee said locating people is the biggest challenge in rural areas. Many are sleeping in abandoned buildings or other private property they can’t access. The volunteers do their best not to miss anyone, while also keeping their own safety in mind.

“Depending on how treacherous it is outside, sometimes we’ll go into the woods,” Hahn said.

In addition to gas station parking lots, they’ve seen several third-shift workers parked at local factories who are living in their cars.

Each January count isn’t released until December, even though lawmakers will soon set housing and emergency shelter funding for the following two years in the 2025-27 state budget.

In 2024, there was an 18% increase in the homeless count nationwide based on the count taken that January. In rural Wisconsin the increase was 9%. In Jefferson County the volunteers recorded three homeless people in 2024. In 2025, the final tally was 13 — a number that likely still doesn’t come close to capturing the true population.

Why does the PIT count happen during the coldest month of the year?

HUD determines that the yearly PIT count must be conducted on the same night in January in every state across the country. Each Continuum of Care — regional organizations operating under HUD that carry out the counts — may conduct a July count in addition to the mandated one in January.

“They want us to go out in the middle of the night because they feel that’s when people would be sleeping, and they would be hunkered down in their standard spots,” said Diane Sennholz, who leads the count in Lincoln, Marathon and Wood counties. “If we were to go out during the day, they might be at the library or the grocery store or walking around.”

Snow falls as Britanie Peaslee and Sandy Hahn drive to various parking lots, parks and gas stations across Waterloo during the annual PIT count on Jan. 22, 2025, in Jefferson County in southern Wisconsin. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Wisconsin’s Balance of State CoC, which covers all 69 counties in Wisconsin besides Milwaukee, Dane and Racine, requires each county in its jurisdiction to carry out a summer count. Others, like Dane County, typically conduct only the required January count.

Frigid temperatures tend to drive more people into emergency homeless shelters, making the count easier. That model might work in cities, but in rural areas like Jefferson County, there are no homeless shelters.

Out of necessity, those experiencing homelessness in a county with no shelters will do everything they can to stay on a friend’s couch or find somewhere warm, making them harder to find and impossible to include in the count. Those temporarily staying with a friend or family member don’t count.

Jefferson County’s summer PIT count has increased each year since 2021 — a trend that can be seen statewide. In 2022, the county’s January count was zero compared to seven recorded in the summer count.

“We definitely don’t find as many in January as we would in summer,” Hahn said. “People are more willing to open up their barns, their garages, their extra bedroom, especially on weeks like this when it’s negative 40.”

Peaslee and Hahn, who are both involved in the community’s poverty-fighting coalition, know the problem is worse than what the count portrays.

“We’re not finding an eighth of how many are truly out there,” Peaslee said.

The PIT count’s pitfalls

On the night of the count, Hahn and Peaslee headed to a truck stop in Johnson Creek where people are known to sleep in their cars. The vehicles were lined up on the farthest end of the lot. One person refused to roll down the window and speak to them.

It happens often, but Peaslee and Hahn can’t blame them. After all, it’s the middle of the night, and they are two strangers who come bearing a four-page survey. HUD requires the volunteers to gather as much information about the individual as possible.

Sandy Hahn talks to someone sleeping in a car in the parking lot behind the Pine Cone Travel Plaza in Johnson Creek, Wis. She found a handful of people sleeping in their cars in the parking lot, including a mother with a young child in one car. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

The pair spoke to someone in another car who knew the individual and confirmed they were unhoused, leading Hahn to fill out an observation form. Volunteers have seven days following the count to attempt to make contact with those individuals again to confirm whether they were homeless on the night of the count. Without that confirmation, they can’t be counted.

The following week, Hahn had no luck tracking down the individual. The person was placed on an observation sheet, but not included in the official count.

Volunteers are not allowed to assume that someone is “literally homeless” in accordance with HUD definitions. But Hahn noted that the car was running in the middle of the night for warmth and there were blankets covering the windows for privacy. Unhoused people who could otherwise be counted are being missed in these instances.

“If somebody has all these personal belongings in their car, you can kind of tell at that point that they’re experiencing homelessness,” said Lyric Glynn, who leads the count in Kewaunee, Door, Manitowoc and Sheboygan counties. “But we can’t count them all the time because they’re sleeping and we haven’t been able to do a survey with them.”

Britanie Peaslee, right, closes the trunk after unloading blankets as she and Sandy Hahn check for people sleeping in their cars Jan. 22, 2025, in Johnson Creek. The annual “point in time” count of homeless people in the United States happens on the same night in January. Advocates note several limitations in the methodology, including a recent U.S. Supreme Court decision that could drive more homeless people into hiding. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

In January 2025, two individuals in Jefferson County ended up on the observation form instead of being recorded in the official count. In July 2024, that number was 10.

The day after the count, Hahn makes calls to determine how many hotel vouchers were distributed that night. Those who are unhoused and temporarily staying in a hotel are counted in the count, but only if they’ve received a voucher for their stay. HUD specifies that if they’re paying for the room themselves, or if someone else is paying for them, they cannot be included, excluding even more of the population from the count.

In Jefferson County, Hahn said those motel vouchers are hard to come by due to minimal funding. People in hotels often pay through other means.

“There are so many barriers,” Peaslee said.

Counts tied to community’s level of need

While federal funding for housing and shelter programs isn’t directly tied to the results of the count, it is used in determining a community’s level of need, according to Ann Oliva, CEO of the National Alliance to End Homelessness. The federal McKinney-Vento Act also requires HUD to determine whether a community is reducing homelessness, and the count is one of multiple criteria scored in the evaluation.

Despite its flaws, Wisconsin’s PIT count shows that statewide homelessness has been increasing. In the “balance” of the state, the mostly rural homeless population increased from 2,938 individuals in 2023 to 3,201 in 2024, the highest number recorded since 2017.

Britanie Peaslee walks in the parking lot behind the Pine Cone Travel Plaza in Johnson Creek., during the PIT count on Jan. 22, 2025. There was a marked increase in homeless people identified during the annual January count of homeless people in Jefferson County, but those numbers won’t be reported until December, long after the state finalizes its two-year budget plan. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

In 2020, a federal moratorium established a temporary pause on evictions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. But the federal government lifted that measure in August 2021.

Glynn said she has concerns about lawmakers, agencies and other officials relying on more than year-old PIT count data.

“When they’re using outdated numbers from years ago, especially early pandemic numbers, they’re not gauging what happened after the pandemic when the eviction moratorium ended and when individuals started getting evicted from units,” Glynn said.

The delayed release of these yearly counts is also a problem when applying for local grants, Glynn said. Application reviewers often look at counts from the previous year. The CoCs have the most recent totals, which sometimes don’t match HUD’s latest figures.

In a state budget year, it would help if officials could have earlier access to the latest counts, Glynn said.

In the state’s 2023-25 biennial budget, the Legislature rejected Gov. Tony Evers’ recommendations to spend some $24 million on emergency shelter and housing grants, as well as homeless case management services and rental assistance for unhoused veterans.

The Legislature also rejected the $250 million Evers proposed for affordable workforce housing and home rehabilitation grants.

Sandy Hahn, left, and Britanie Peaslee, right, knock on a bathroom door at Waterloo Firemen’s Park to check if anyone is sleeping inside. Hahn and Peaslee did not find anyone sleeping at the park. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Lt. Gov. Sara Rodriguez joined a group of volunteers in western Wisconsin on the night of the count in 2025, where she expressed concerns about rising housing costs and emergency shelter services. She said Evers’ budget “is going to have those types of investments.”

Evers is set to announce his 2025-27 state budget proposal on Feb. 18.

Court ruling could affect counts

In June, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that municipalities can enforce bans on homeless people sleeping in public places. Oliva predicts this ruling will impact the count results in 2025.

“I wonder what will happen in places that have been ticketing and fining people. Those people are going to hide,” Oliva told Wisconsin Watch. “Why would you want to be found, especially if you know that it’s possible that you’ll get ticketed or put in jail for being homeless?”

Volunteers like Peaslee and Hahn, who work with the homeless population in their community, still see value in conducting the count. For them, it is an opportunity for outreach and allows them to offer resources to those with whom they haven’t previously made contact. They remind people they are more than a number.

“Yes, you need the gritty details to report to HUD, but really making them feel like they are human and that their story matters,” Peaslee said. “And we’re not just putting down a data point to have a data point. We want to know, how can we help you?”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us