Wisconsin's Homeless Population Has Grown, And Not Just In Cities

Madison might be at the center of Wisconsin's loudest discussion about homelessness right now, but the problem extends far beyond the state's capital city. In fact, the majority of the state's homeless people documented in a 2015 federal reportwere outside the Madison and Milwaukee areas.

July 19, 2016

Homeless Campsite With Car and Tents

Madison might be at the center of Wisconsin’s loudest discussion about homelessness right now, but the problem extends far beyond the state’s capital city. In fact, the majority of the state’s homeless people documented in a 2015 federal reportwere outside the Madison and Milwaukee areas.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development counted 6,057 homeless people in Wisconsin in 2015. Of those, 1,521 were in Milwaukee County and 771 were in Dane County (Madison). These numbers are from from definitive, though.

These figures indicate that Milwaukee and Dane counties host a disproportionately high percentage of the Wisconsin’s homeless population, but volunteer counters still found another 3,765 people elsewhere around the state. Mid-size cities in Wisconsin account for some of those individuals, as a La Crosse church’s recent struggle to serve homeless residentsdemonstrates, but the issue also extends beyond these communities.

Millie Rounsville, CEO of the Superior-based Northwest Wisconsin Community Services Agency, said the perception of homelessness as just an urban problem ignores its very real presence in rural areas of the state. In northwestern Wisconsin, her organization often finds more people in rural Ashland and Bayfield counties than they do within the city of Superior. Superior’s homeless shelters are routinely full, she noted, which means they’re not much help to people in nearby rural areas.

“That’s kind of been one of our pet peeves, is people assume in our communities that we don’t have a homeless problem because you don’t see shopping carts like in the big cities, or that it’s too cold, and that’s not the case,” Rounsville said.

The Northwest Wisconsin Community Services Agency is one of hundreds of non-profits around the U.S. that will dispatch volunteers at the end of July for a “point-in-time” count of people living in public spaces and homeless shelters. These counts, conducted twice annually, supply the raw data for HUD’s statistics on homelessness.

Given the transitory nature of homelessness, counting people without permanent homes in a consistent and reliable way is difficult. It’s fairly easy to count people staying in shelters, or people who’ve had contact with an organization serving the homeless. But volunteers canvassing streets and other public places can’t get to every spot where homeless people might be settling down or gathering, especially if winter weather is making it hard to get around.

“It depends how many volunteers you have to go and count, the weather that night, are the volunteers willing to go and count under bridges?” said Joe Volk of the Wisconsin Coalition Against Homelessness.

Additionally, many homeless people, especially families, might be temporarily staying in a friend or family member’s home, or staying in a hotel room (some organizations provide vouchers for homeless clients). Volk said the point-in-time count misses these people almost entirely. Rounsville added that these counts include some, but far from all, people who’ve been displaced by domestic violence.

Counting homeless people in rural areas presents its own challenges. For instance, Rounsville sends her counters to campsites in northwest Wisconsin.

“It’s a little harder to do campsites, because you’re trying to figure out who’s homeless and who’s just camping,” she said. Rounsville added that July’s flooding in northwestern Wisconsin, and the road damage it has caused, will likely complicate the summer counting process.

The homelessness numbers HUD issues include counts from more rurally focused organizations like Rounsville’s, but don’t place much emphasis on them. The agency’s annual reports categorize Wisconsin into four areas: Milwaukee County, Racine County, Dane County and “balance of state” — Wisconsin’s other 69 counties, all lumped into one statistical “region.” That makes it difficult to learn specifics about Wisconsin’s third- and fourth-largest cities (Green Bay and Kenosha), not to mention understand how homelessness is distributed across smaller cities, suburbs, and rural areas.

The annual HUD survey may be under-counting homeless people by a factor of thousands. Volk estimated Wisconsin may have as many as 20,000 homeless residents.

“[The HUD method is] primarily heavy on counting single adults,” he said. “Many of us, including myself, don’t think it’s a very accurate picture.”

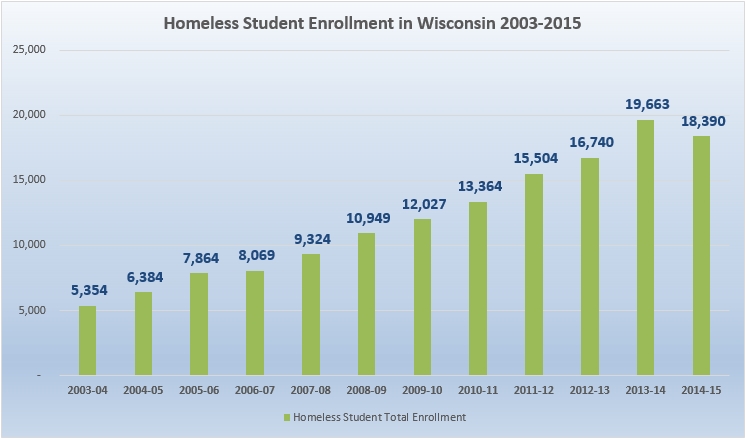

One basis for Volk’s rough estimate is the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction’s data on homeless students, gathered from social workers in schools across the state. In the 2014-15 school year, DPI estimated 18,390 homeless children were enrolled in Wisconsin’s public schools. (Numbers for the 2015-16 school year are not due to the state until August.) Wisconsin’s largest districts (Milwaukee, Madison, Kenosha, Green Bay, Racine) accounted for about 8,200 of these children, but many others were scattered throughout smaller districts a few dozen at a time: 61 in the Rice Lake Area School District, 71 in the Menominee Indian School District, 33 in the Merrill Area School District and so on.

When the nonprofit agency Couleecap issued a report in 2015 about homelessness among students in four southwestern Wisconsin counties, oneLa Crosse schools official said the district likely served even more homeless students than the report estimated.

The DPI’s count of homeless children bolsters Volk’s assertion that the federal survey is likely missing large numbers of homeless families. When the DPI looked at where homeless students were residing in the 2014-15 school year, it found that 14,373 were in a “doubled up” situation — a family living in a relative or friend’s home — and 1,409 were staying in hotels. That left only 2,608 homeless students in situations where a point-in-time volunteer would be likely to count them — in a shelter or living outside.

Despite their respective blind spots, DPI’s tracking of homeless students and the federally organized street/shelter counts have found the same trend: Homelessness has increased significantly in Wisconsin over the past decade.

During the 2004-5 school year, DPI counted 6,384 homeless students, with the number steadily climbing until it peaked at almost 20,000 in 2013-14. Meanwhile, HUD’s 2015 report noted that from 2007 to 2015, homelessness in the United States decreased by 12.8 percent, despite the recession, but homelessness in Wisconsin increased 24.5 percent. Moreover, HUD’s national numbers don’t show a huge spike in homelessness during the recession, and might not account for a large number of people who moved in with relatives or friends after losing their homes in a foreclosure or eviction.

This increase in homelessness didn’t happen in just the more populated areas of Wisconsin. In DPI’s numbers, the larger districts accounted for a lot of the increase — Racine School District’s number of homeless students more than doubled between 2005 and 2015 — but many smaller districts went from having zero or just a handful of homeless students to several dozen.

The state and federal statistics are a reminder that homelessness doesn’t always take the forms people expect, or happen where people might expect it. Rounsville said many Wisconsinites don’t realize they may have neighbors or co-workers who could be one personal or financial mishap away from losing everything. Roundsville said the clients she works with remind her of “how close a lot of people are to homelessness.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us