Wisconsin's Early Norwegian Press Was A Cohesive Force For Immigrants

When large numbers of emigrants from Norway started making their way to the United States in the mid-19th century, Wisconsin was one of the first places they settled.

May 8, 2019

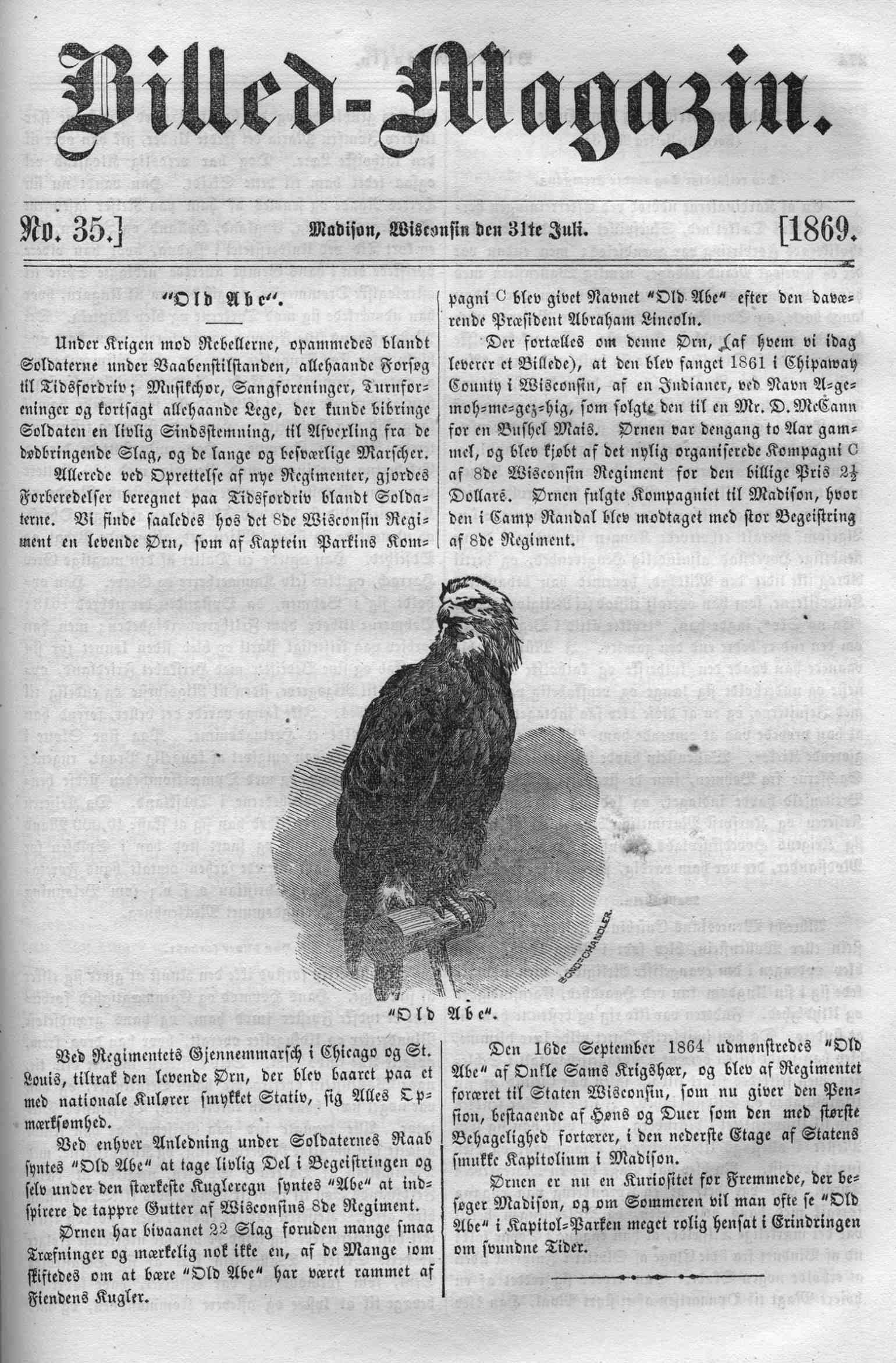

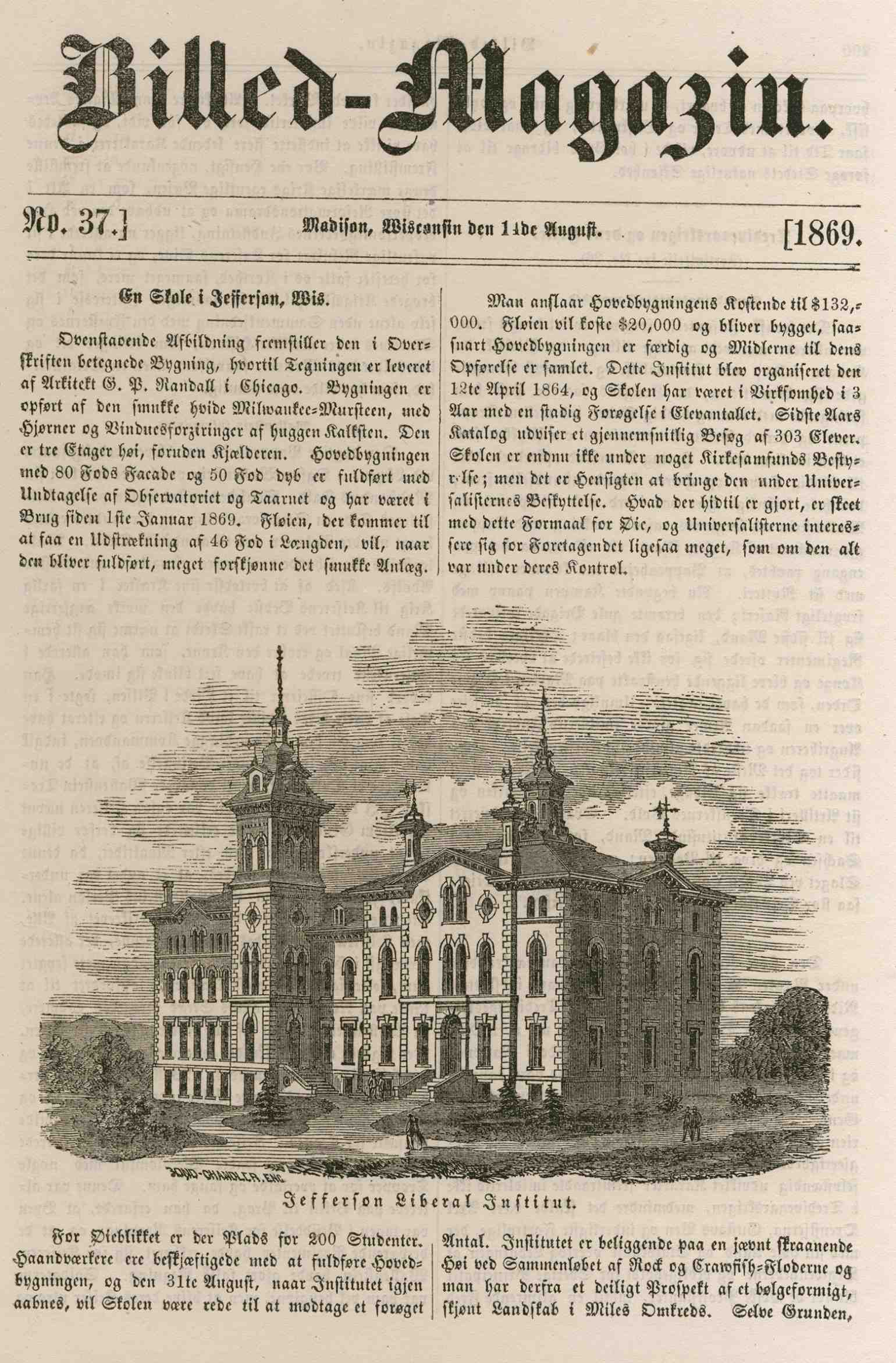

Billed-Magazin No. 35 cover with Old Abe crop

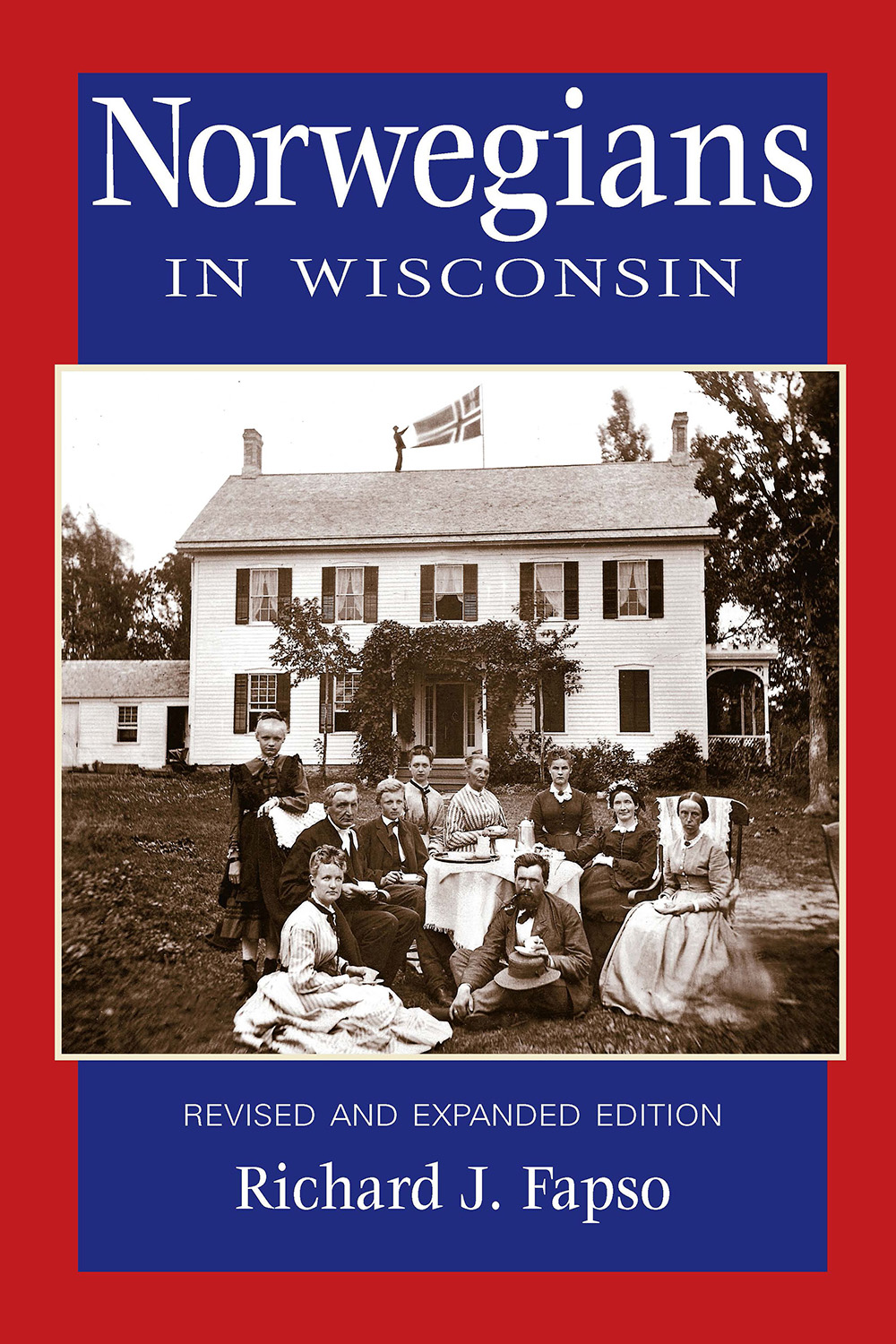

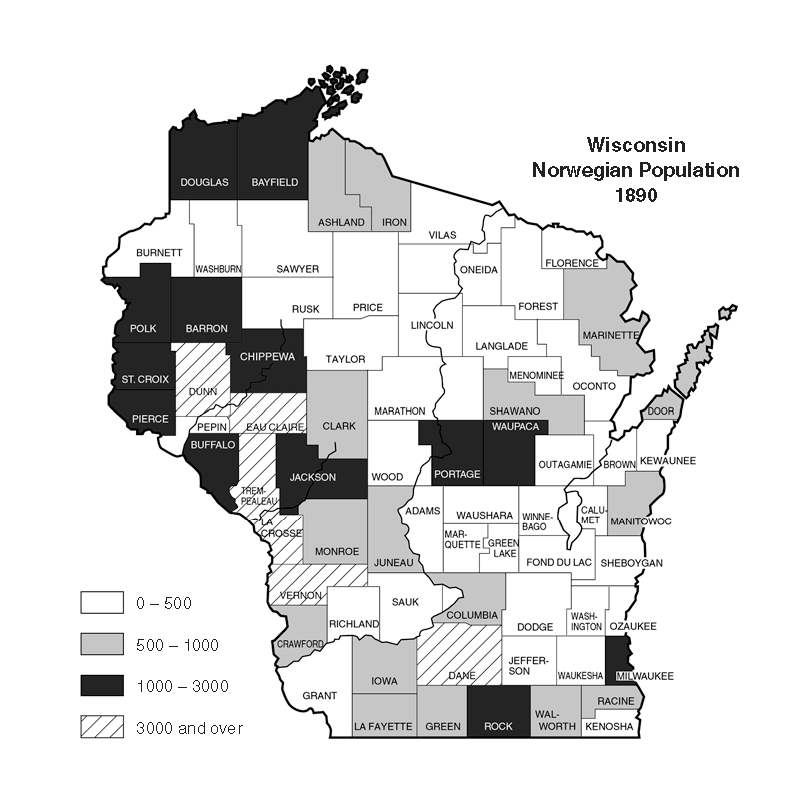

When large numbers of emigrants from Norway started making their way to the United States in the mid-19th century, Wisconsin was one of the first places they settled. Norwegians initially established communities in southeastern Wisconsin and subsequently expanded across broad swaths of the state, particularly in its western reaches along tributaries of the Mississippi River. Wisconsin was only briefly the primary destination for Norwegian and other Scandinavian immigrants, who would turn their eyes toward Minnesota and the Dakotas following the Civil War. More than a century and a half later, Americans who claim Norwegian ancestry are heavily concentrated in the upper Midwest. The early experiences of this immigrant community are explored in the 2001 book Norwegians in Wisconsin: Revised and Expanded Edition, written by Richard J. Fapso and published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press as part of its People of Wisconsin series. An excerpt from the book describes the founding of Norwegian-language newspapers and magazines in the mid 19th century, and explores the role they came to play in shaping and sustaining their communities. Media published or broadcast in the native languages of immigrant groups in the U.S. has long been and continues to play an influential role in their lives.

Another institution of major influence on Norwegian group life in America was the Norwegian-American press. Newly arrived immigrants, however, were not accustomed to American journalistic traditions.

In 19th century Norway, newspapers were few, expensive, and of little interest to the general public. Although literacy was relatively high, the common farmer did not concern himself with questions of public affairs outside his own parish or village. Overcoming this feeling of indifference among the immigrants was the biggest obstacle for the founders of the Norwegian-American press.

As immigration in Wisconsin increased and spread across the state, many began to see that sources of information other than the local community and church were necessary. To meet this need the early immigrant press sought to reach and serve people not only in Wisconsin but also in settlements throughout the country. Attempting to be more than merely local newspapers, the news covered a wide range of intellectual and social concerns.

Unlike the press in Norway, nearly all Norwegian-American newspapers remained very close to the grassroots. Their service was an immediate one: to inform those who could not as yet read the English language. In doing so they instructed their readers in the history and government of the United States, reported the news of Europe and Scandinavia, provided information concerning social and religious events, and kept the reader abreast of agricultural and business news.

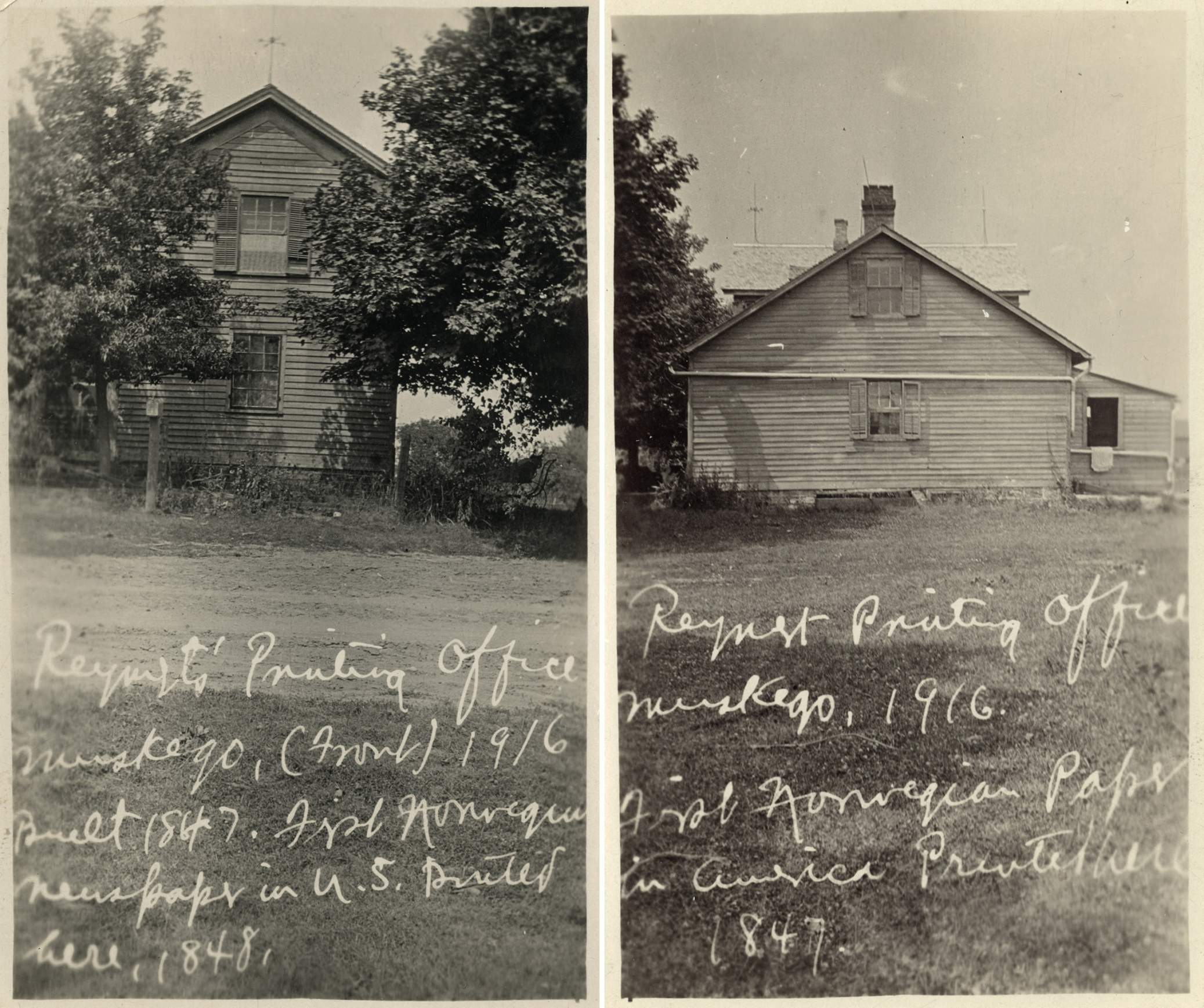

The first Norwegian-American newspaper, Nordlyset (Northern Light), was established in Muskego in 1847. In its first issue the editor state their intention: “Besides information about the constitution of this country and reports from Scandinavia, historical, agricultural, and religious news, we intend to bring contributions from private individuals and everything else that is suitable and useful for the information and entertainment of our readers. The editors will make every effort to preserve the strictest possible neutrality in matters of politics and religion.”

With this dictum the paper appeared regularly for three years, after which time the editors disbanded.

When Nordlyset ceased publication, other newspapers filled the vacuum. In the early 1850s the clergy began to take an interest in establishing a newspaper that would serve the interests of the emerging Norwegian Lutheran Church. Out of this desire came the Emigranten (The Emigrant). Founded by Reverend C.L. Clausen in 1852, this paper became an influential and long-lived pillar of Norwegian-American journalism.

Given the American system of government, the ethnic press found it impossible to remain politically neutral. Prior to any election many editors felt compelled to express their support for a local or national candidate. From its conception the Emigranten assumed an “independent Democratic” approach to state and local politics. Reflecting the views of the majority of its readers, it took a position against slavery, favored a liberal public land policy, and shared the hostile frontier attitude toward the land speculator.

As events in the 1850s let America closer to civil war, the Emigranten’s editorials dealt increasingly with the political issues of slavery and the preservation of the Union. The Republican party, with its strong stand against slavery and its promise of free land under the Homestead Act, began attracting the support of Norwegian voters.

In 1857 the Emigranten cemented its stand on the issues by proclaiming “No Slavery for Black or White” and found itself rapidly moving to the Republican side.

Involved in American political and social events, the Norwegian-language press continued to fulfill various functions. While continuing to occupy much of its space with news from Norway and Europe, it also solicited accounts from Norwegian settlers in the new frontiers of the West and published several of the responses. Controversies of the day were aired, and one could always learn time and place of the various organization meetings in the news.

In the last quarter of the century many, especially those who had immigrated to America in the early periods, became concerned with the speed with which the newly arrived immigrants dropped their cultural traits. Dress, diet, language, economic success, in addition to the strong nativist pressure to conform, convinced the immigrants to modify their Norwegian customs and adopt American ways. In response to this influence, the ethnic press attempted to remind the immigrants to appreciate their own nationality.

Printed in the pure Norwegian literary form, the press served as a cohesive force, setting up common interests among all the various Norwegian dialectal groups. In doing so, the ethnic press actively preserved the most important cultural trait of any group — its native language — and helped make possible the boom in local and national societies that occurred around the turn of the century.

This item was excerpted from Norwegians in Wisconsin: Revised and Expanded Edition, published by Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

Richard J. Fapso is an author for the Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us