Wisconsin prisons restrict books and mail to keep drugs out, but some staff still bring drugs in

Critics say the state Department of Corrections is limiting prisoner access to information when it halted the efforts of the nonprofit group Wisconsin Books to Prisoners, even as wider entry points for smuggling drugs remain open.

Wisconsin Watch

October 8, 2024

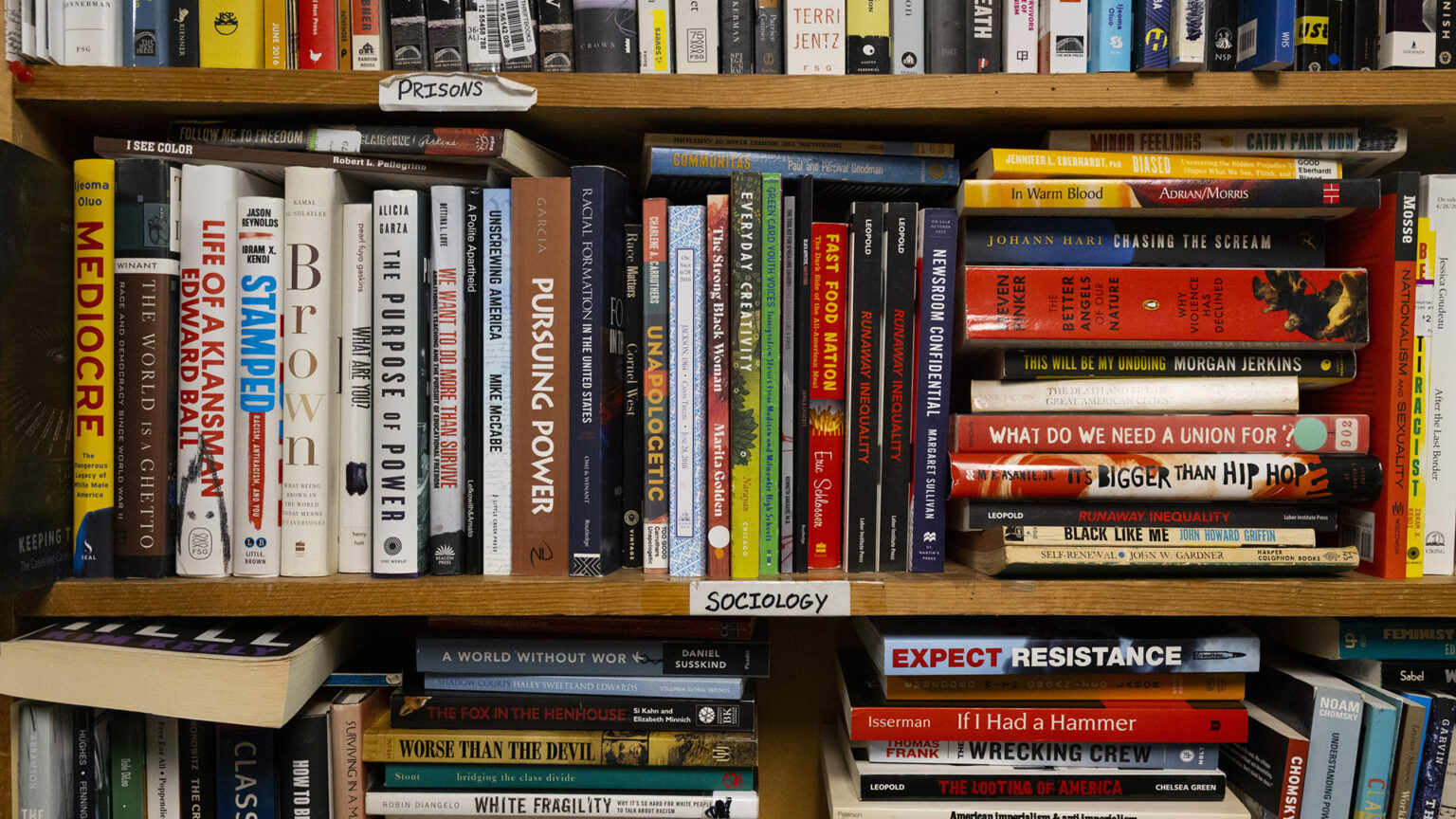

Stacks of books are lined up in the Wisconsin Books to Prisoners library on Sept. 20, 2024, at the Social Justice Center in Madison. Wisconsin Books to Prisoners, a volunteer-run nonprofit, has sent over 70,000 books to state prisons since 2006. But the Wisconsin Department of Corrections has halted the group's work, calling the move necessary to stem the flow of drugs into prisons. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

This story was produced and originally published by Wisconsin Watch, a nonprofit, nonpartisan newsroom.

The Wisconsin Department of Corrections has halted the work of a nonprofit that donated used books to prisoners for nearly 20 years, calling it necessary to prevent drugs from entering state prisons through secondhand books.

The move is drawing pushback from leaders of the nonprofit Wisconsin Books to Prisoners and prisoner rights advocates. They say the department is limiting inmates’ access to information while failing to narrow wider entry points for drugs, like prison staff.

The used book ban comes after Wisconsin rerouted prisoner-bound mail out of state in the name of blocking drug shipments — an effort that has cost millions yet has had little visible impact on the numbers.

As they restrict books and mail shipments, Wisconsin prison officials have shared less about plans to stop prison employees from bringing in drugs.

That’s despite the 2023 launch of a federal investigation into employees suspected of smuggling contraband into Waupun Correctional Institution. Separately, multiple Wisconsin prison workers have faced charges related to drug smuggling in recent years.

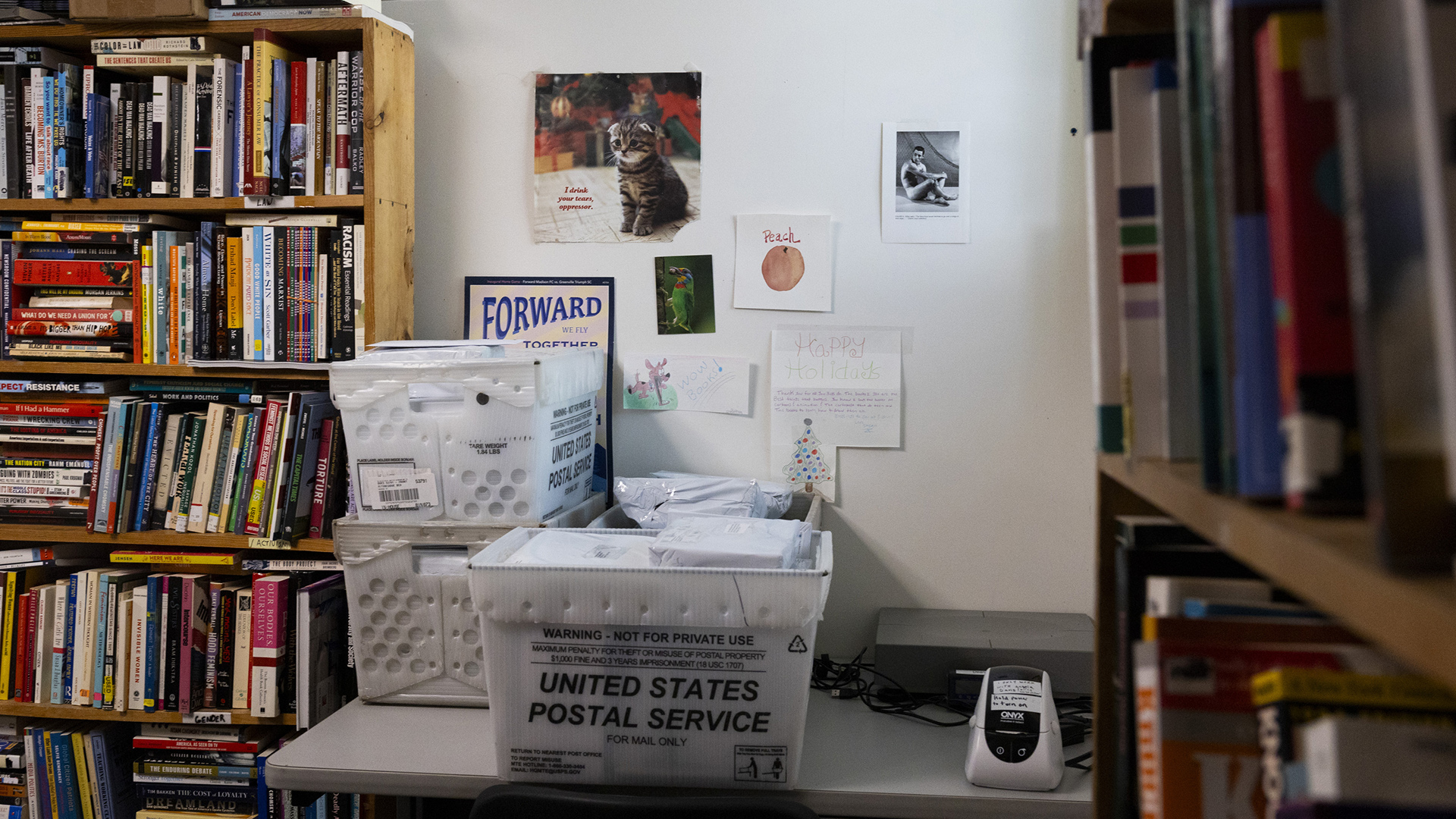

Returned packages are stacked alongside bookshelves in the Wisconsin Books to Prisoners library on Sept. 20, 2024, at the Social Justice Center in Madison. The Wisconsin Department of Corrections says it will no longer allow used books to be sent to prisoners, effectively halting the volunteer-run nonprofit’s work. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Prison officials ban used book donations

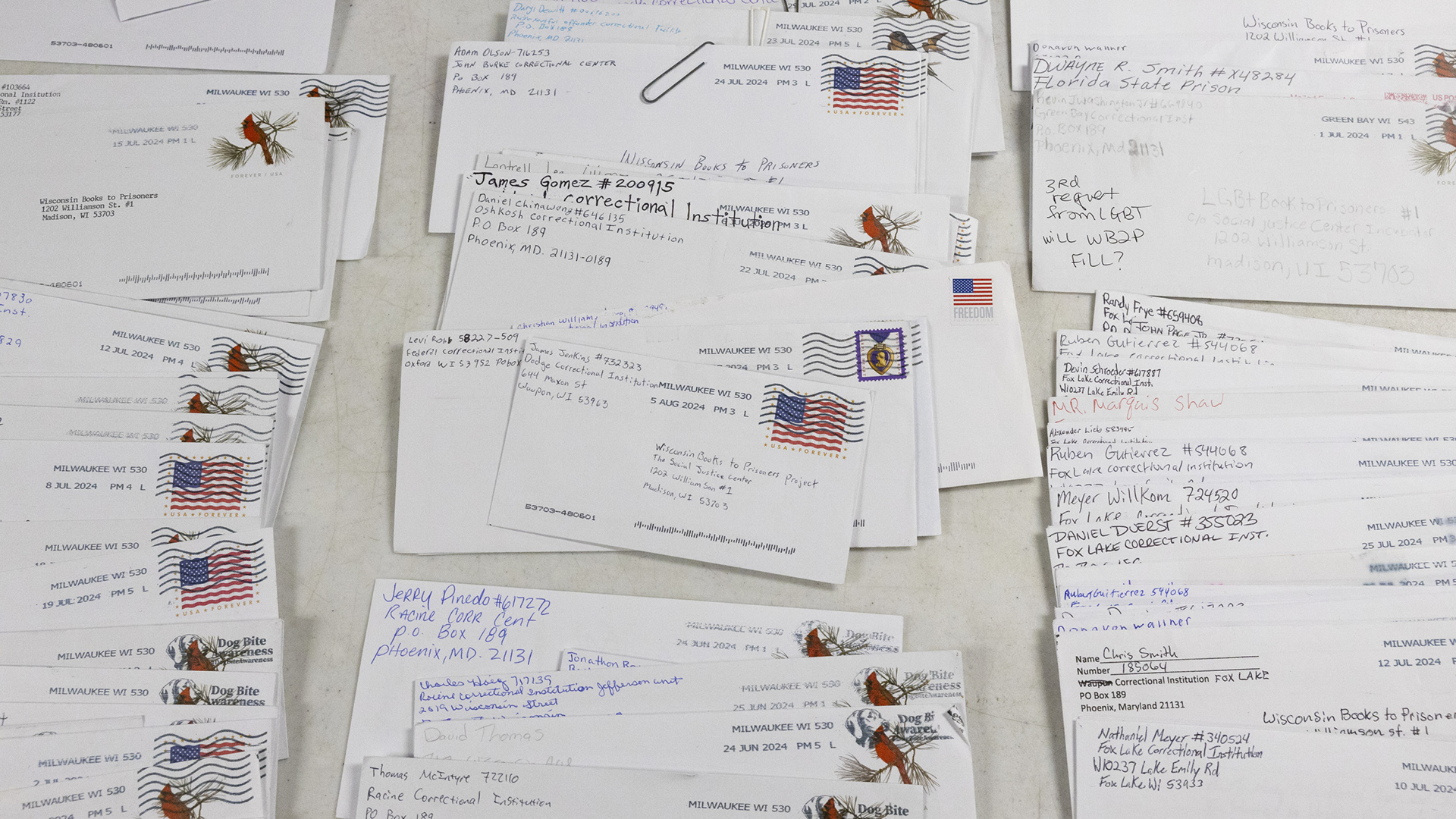

Wisconsin Books to Prisoners (WBTP), a small volunteer-run organization, has sent over 70,000 free books to state prisons since 2006.

Camy Matthay, the group’s director and co-founder, said she was alarmed in August to learn state prisons would no longer accept the group’s used books.

“The decision to bar WBTP from sending books unnecessarily restricts incarcerated peoples’ access to valuable educational resources, particularly when many facilities suffer from underfunded, outdated, or non-existent library service,” Matthay’s group wrote on social media when announcing the ban.

“We just want to send books to prisoners, that’s all,” Matthay said in an interview.

The organization inspected all books before sending to ensure they met prison “clean copy” criteria: no highlighting, underlining or marks of any kind, she said.

In an Aug. 16 email to the nonprofit, Division of Adult Institutions Administrator Sarah Cooper wrote that her agency is not concerned with the organization itself, “but with those who would impersonate your organization for nefarious means.”

“Bad actors” may send packages and books laced with drugs that “appear to be sent from the Child Support Agency, the IRS, the State Public Defender’s Office, the Department of Justice and individual attorneys,” she wrote.

The corrections department announced its latest ban of used books in January. Then Oshkosh Correctional Institution officials in February and March detected drugs in three shipments of books purporting to be from Wisconsin Books to Prisoners, spokesperson Beth Hardtke told reporters Sept. 30 in an email.

That was news to Matthay, she said Sept. 30. The department never notified the group about the incidents, nor did Cooper’s August email mention them.

Letters containing prisoners’ unfulfilled book requests are shown at the Wisconsin Books to Prisoners library on Sept. 20, 2024, at the Social Justice Center in Madison. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Latest effort to restrict book donations

This isn’t the first time restrictions have threatened the group’s work.

Prison officials cited drug concerns in halting the nonprofit’s donations in 2008 before eventually agreeing to let it send only new books, following ACLU of Wisconsin intervention. In 2018, the department clarified that the nonprofit, as an approved vendor, could send used books so long as they were clean copies. It reaffirmed that decision in 2021.

Hardtke said the latest restrictions don’t specifically target Wisconsin Books to Prisoners. They are instead part of a broader ban on all secondhand book deliveries. Prisoners may still receive new books sent directly from a publisher or retailer with a receipt, she said.

Matthay’s group cannot keep up with demands while being limited to only new books, she said.

The policy will chill prisoners’ access to information, said Moira Marquis, a senior manager at the freedom of expression advocacy group PEN America. Marquis authored the report “Reading Between the Bars,” which detailed state book restrictions nationwide.

Wisconsin Books to Prisoners sent donated books to inmates for free to address a specific barrier to information. Many prisoners, who in 2023 made as little as five cents per hour in jobs behind bars, cannot afford to buy new books from retailers.

“If you’re going to limit somebody’s First Amendment rights excessively, you really should have a very strong burden of proof that not only is this necessary, but also that it’s effective,” Marquis said.

Wisconsin Watch asked the corrections department for evidence that necessitated the ban.

“Unfortunately, in recent years individuals have repeatedly used paper, including letters and books, as a way to try to smuggle drugs into DOC institutions,” Hardtke said in an email.

The department since 2019 has flagged 214 incidents of drugs being found on paper, representing a quarter of all 881 contraband incidents flagged during that time, according to figures Hardtke provided.

“DOC is continuing the conversation with Wisconsin Books to Prisoners in the hopes we can come to an agreement to help fulfill the reading requests of those in our care and do so safely,” Hardtke wrote.

Matthay in August asked the department if providing tracking information on its packages could help it verify that book shipments were indeed coming from Wisconsin Books to Prisoners.

The department has yet to respond, she said Sept. 30.

Files on Wisconsin state prisons sit in a box atop bookshelves at the Wisconsin Books to Prisoners library on Sept. 20, 2024, at the Social Justice Center in Madison. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Millions spent rerouting prison mail to Maryland

The corrections department’s broader efforts to restrict mail do not appear to have slowed the flow of drugs. The department counted more incident reports of drugs being found on paper (55) thus far in 2024 than it did in 2021 (49), the year it overhauled its mailing system, the figures Hardtke provided show.

Not all incident reports flagged as drug-related turn out to actually be so, Hardtke noted, and the figures may not account for drug-related incidents logged in separate medical or conduct reports.

In December 2021, the department began rerouting all prisoner-bound mail to Maryland, where a company called TextBehind scans each piece of mail and sends a digital copy to those incarcerated. The department has paid nearly $4 million for those services since they began, according to information Wisconsin Watch obtained through an open records request.

Some incarcerated people told Wisconsin Watch the loss of physical mail has increased their feelings of isolation. They can no longer hold the same handwritten letters and photographs their loved ones sent; photocopies aren’t the same.

“I don’t get to smell the perfume on a letter. I don’t get the actual drawings my kid sends me. It takes away from the sentimental value of it,” said a Waupun prisoner who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution.

A range of research has shown that maintaining connections to loved ones improves the likelihood that a prisoner will reintegrate into society and avoid recidivism.

The prisoner said the mail policy hasn’t stopped the flow of drugs into prison.

“Every day I smell weed,” he said. “They’re trying to blame us for the drugs, but if the administration doesn’t hold their staff accountable for their actions, it won’t solve the problem.”

Kyle Wienke, liaison to the Wisconsin Department of Corrections for Wisconsin Books to Prisoners, poses for a portrait in the group’s library on Sept. 20, 2024, at the Social Justice Center in Madison. He says the volunteer-run nonprofit has about 250 unfulfilled book requests from prisoners since the corrections department banned used book donations earlier in 2024. (Credit: Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Lockdowns don’t stop drug flow

Wisconsin in recent years has locked down prisons, limiting inmate movement and privileges to alleviate staffing shortages. Drugs kept flowing even after in-person visits and direct mail to prisoners stopped.

The department counted 214 total drug-related contraband incident reports in 2024, up from 142 a year earlier and 164 in 2022.

In 2023, a U.S. Department of Justice investigation into a possible drug and contraband smuggling ring prompted the state to place 11 Waupun prison employees on leave. In September, a former Waupun prison employee was convicted of smuggling contraband into prisons under the guise of completing repairs.

And in October 2023, three months after state officials asked federal authorities to investigate staff-led smuggling inside Waupun’s prison, 30-year-old Tyshun Lemons was found dead from fentanyl poisoning. In June, prosecutors criminally charged nine Waupun prison workers, including the former warden, following multiple inmate deaths, including Lemons’.

At least two dozen correctional officers have been caught smuggling contraband into Wisconsin prisons since 2019, according to public records obtained by the advocacy group Ladies of SCI and shared with Wisconsin Watch.

Wisconsin Watch is awaiting department records requested Sept. 5 detailing additional information related to recent drug incidents in its adult facilities.

Mail restrictions scrutinized in other states

Multiple states have restricted books and mail since 2015, citing drug smuggling concerns, Marquis said. Meanwhile, prisoners have increasingly relied on electronic tablets, which have come with new limits on what they can read, Marquis said.

Have such restrictions limited the flow of drugs in those states? Not necessarily, news reports have found.

A Texas Tribune/Marshall Project investigation in 2021 found that curtailing mail did not curb drugs found in Texas prisons. Guards wrote up even more prisoners for drugs after the policy change. Prisoners and employees reported that staff were most responsible for smuggling drugs.

Pennsylvania’s prison officials banned physical mail in 2018 after blaming a series of staff illnesses on drugs allegedly sent by mail. But less than five years later, the number of prisoners who tested positive on random drug tests substantially increased, the Patriot-News reported in 2023.

Florida in 2021 stopped all paper mail from entering prisons, citing 35,000 contraband items found in mail between January 2019 and April 2021. But those represented less than 2% of all such items found in the prisons during that period, the Tampa Bay Times reported.

Wisconsin in 2022 issued new screening requirements for people entering prisons and added metal detectors at points of entry. But one Waupun prison worker said screeners at entrances do not routinely inspect employees’ bags or lunches, allowing drugs to pass through undetected. The prison worker requested anonymity because he is not authorized to speak to media.

“If it were me trying to stop drugs, the first thing I would do is come up with a system where employees are screened better,” he said.

To Rebecca Aubart, executive director of Ladies of SCI, the secondhand book ban is an example of how policies touted as safety measures harm incarcerated people.

“To me this policy is another way DOC is blaming families and the people they incarcerate for the problems their staff can’t or won’t address,” she said.

“It’s a false narrative that gets repeated, and when it becomes policy, the false narrative gets reinforced.”

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us