Wisconsin Capitol Capped A Storied Career For George B. Post

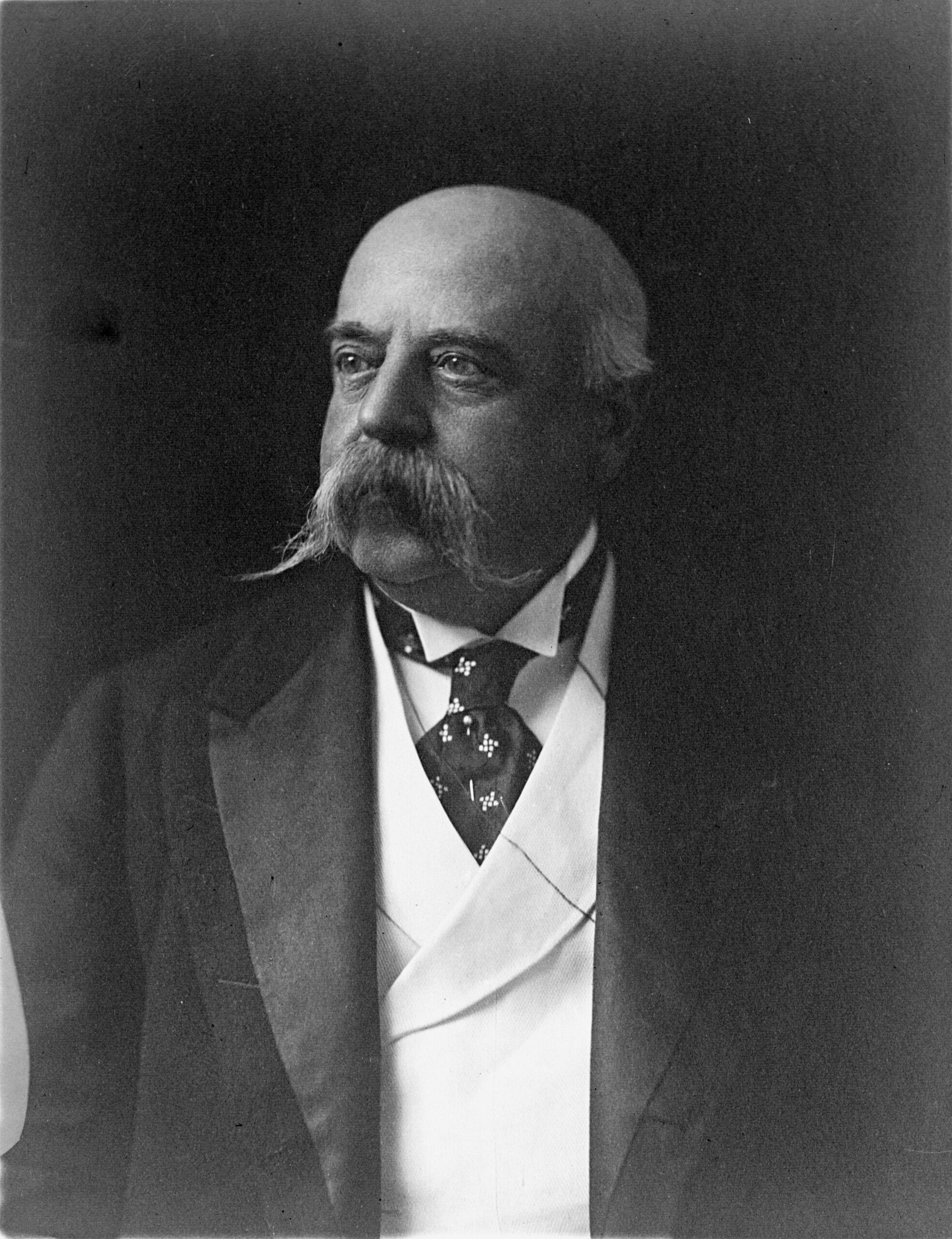

To understand the Wisconsin State Capitol, it helps to look to New York City. That's where the building's architect, George B. Post, lived most of his life and designed many innovative buildings of his era.

December 5, 2017

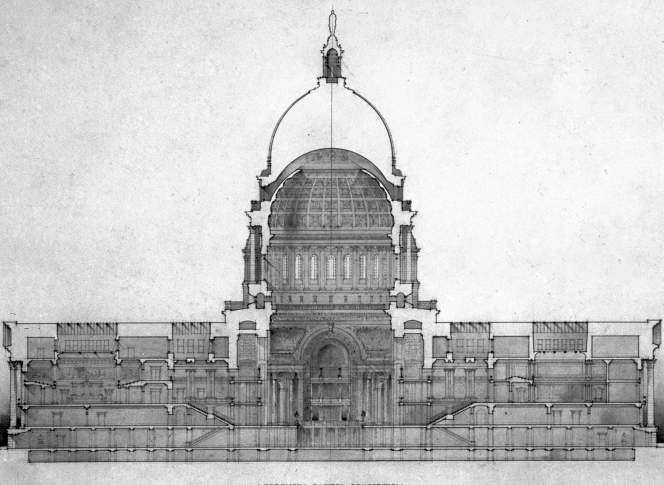

George B. Post architectural drawing of Wisconsin capitol

To understand the Wisconsin State Capitol, it helps to look to New York City. That’s where the building’s architect, George B. Post, lived most of his life and designed many innovative buildings of his era.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Post designed buildings that pushed boundaries of height and explored new ideas about the very ways in which structures can support themselves. By employing novel design and engineering approaches that used steel and wrought-iron frames to support buildings’ exterior walls, he made it easier to the buildings to have more open interior spaces, and in some cases, more windows. Wisconsin’s Capitol, which turns 100 this year, was a late-career highlight for Post, and one might even say a posthumous one — he died in 1913, while it was still being built.

“He was really a preeminent architect of the time — one of those guys we don’t study in architecture school enough, probably,” said Charles Quagliana, a former Capitol preservation architect for the state of Wisconsin, in an Aug. 1, 2017 presentation at the Wisconsin Historical Museum in Madison. In his talk, recorded for Wisconsin Public Television’s University Place, Quagliana offered an overview of Post’s formative years and important works, and explored some of the details of the Capitol’s design and construction.

Post’s major architectural accomplishments ranged from the New York Stock Exchange building to a massive structure at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. Quagliana explained that surveying Post’s career reveals how the architect developed and sometimes wrestled with his ideas about how tall buildings should look and function, and how those innovations influenced the Wisconsin Capitol’s design alongside its more traditional inspirations.

Post was personally quite involved in the building’s construction, making at least 20 train journeys from New York to Madison, which would have been pretty taxing for a man in his late 60s and early 70s. After Post died, both of his sons, who were architects and joined their father’s firm in 1901, would go on to supervise the rest of the construction.

Key facts

- Born in Brooklyn in 1837, Post grew up in New York City, and studied civil engineering at New York University. After graduating, he was hired by preeminent 19th century architect Richard Morris Hunt, and worked with other young architects who would go on to gain prominence, including Frank Furness and Henry Van Brunt. One of Post’s first buildings was a gymnasium built on the Princeton University campus in 1869.

- Post played an important role in the development of skyscrapers. Before the Civil War, most of the tallest buildings in New York City were only three to five stories high. In 1870, he worked as the supervising architect on the Equitable Life Assurance Building on Broadway in lower Manhattan, which at 142 feet was considered tall for the time. Five years later, he would design the 230-foot-fall Western Union Building, also on lower Broadway. Before the end of the century, he would go on to design the New York World Building, which was 349 feet high and, for a couple of years after its construction in 1890, the tallest building in the city.

- Post was from a well-to-do family and well-connected, and ended up designing homes for other wealthy families, including the Cornelius Vanderbilt Mansion, the largest private residence ever built in New York City.

- Post was concerned about the long-term implications of designing taller buildings, like structural corrosion and parts falling off with age. To address these problems, he experimented with different approaches to design and construction to make sure his buildings could support themselves. For the New York Produce Exchange building, built in 1884, he combined different modes of construction such that the internal cast-iron structures held the external walls in place, which was considered an innovation at the time.

- Famed Chicago-based architect Daniel Burnham selected Post as one of the architects to design the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. Post ended up designing the Chicago fair’s largest building, the Manufacturers and Liberal Arts Building, a massive structure with 30 acres of floor area. Through their collaboration on the fair, Post and Burnham became good friends.

- The previous Wisconsin Capitol building was built in the 1850s and 1860s, and was subsequently expanded in the 1880s, but the state government decided that even after these changes, the building was too small. In 1904, a fire destroyed much of the structure, with the worst damage in the middle of the building, as well as in the Assembly and Senate chambers in its eastern and western wings. In an effort to upgrade its facilities, the state held a competition to design a new Capitol building. The first competition failed to draw any suitable designs. The state held a second competition in 1905, and the sole juror for the competition was Post’s friend Daniel Burnham. Post won, beating our four other entries.

- The Wisconsin Capitol Building’s floor plan is known as a saltire, or St. Andrew’s cross, in the shape of an X with four wings that each point in a cardinal direction. Like many other capitol buildings, it draws inspiration from Europe’s grand domed cathedrals, namely St. Paul’s in London and perhaps St. Isaac’s in St. Petersburg. In his earlier designs, Post envisioned the dome being more squat in shape than what ended up being built; in its current rounded form, snow and rain can run off more easily.

- Five different contractors built the Post-designed Wisconsin Capitol over the course of 11 years. This sequence resulted in minor differences between each of the wings. (However, Quagliana said all of the contractors did remarkably well at coordinating with each other and faithfully executing Post’s vision.)

- Post designed the new Wisconsin Capitol a self-supporting steel structure, clad in granite. Over the course of its first century, the building has had very few issues with structural corrosion.

- Construction of the new Wisconsin Capitol was officially completed in spring or summer of 1917 — because of the onset of World War I, records are a bit unclear, and there was not an official dedication ceremony for the building at the time.

- Post was well-connected with the art community, and known for getting artists to work on his building projects. He drew on these connections for Wisconsin’s Capitol. The building includes murals by Edwin Blashfield, Kenyon Cox and Albert Herter, along with the work of several sculptors, the most iconic being “Wisconsin” by Daniel Chester French, which sits atop the dome.

Key quotes

- On Post’s design for the Western Union Building: “You can see that he’s sort of struggling with what high-rise buildings should look like. It’s a little bit clunky perhaps, but it’s a pretty big building. Two hundred thirty feet in 1875 … dwarfs everything else in the city. It’s a cage construction, which means it has the cast iron columns and wrought iron girders that support the floors and the roof, but the exterior walls support themselves. So they’re masonry and they support themselves.”

- On the previous Wisconsin State Capitol building: “It was nice. It was simple. Not really fireproof construction, but, you know, a lot of vaults and brick and cast iron and wrought iron beams. The Assembly wasn’t a grand space, but it was certainly nice for that time. The Supreme Court was pretty nice. The Supreme Court probably had the most decoration of any room, and there wasn’t much but it was a nice building.”

- On why the destruction of Wisconsin’s previous Capitol building might have been a good thing: “I don’t say this lightly: ‘Thank God we had a fire.’ Right? Because we would be dealing with this building today, and it would be really tough. I mean, this is what some of the states, like Michigan has a capitol from this age, or Kansas, and they’re really difficult buildings to work with because they have archaic materials and some weren’t built that well.”

- Ranking state capitol buildings: “Pennsylvania is probably one of the nicer capitols in the U.S. I think ours is maybe the third best. Pennsylvania is right at the top, maybe Providence [Rhode Island] is the other one. Really super capitols. I think ours is in the top three for sure.”

- On what the current Wisconsin Capitol’s construction workers experienced on the job: “You can imagine what they saw when they were working on the dome in 1912, 1913 and 1914. Madison only goes maybe to University Heights and maybe out to Atwood Avenue. It’s not very big. They’re looking at the wilderness, basically. It must have been pretty exciting to be working on it at that time. I’m not sure where even all the workers came from.”

- On the Wisconsin Capitol’s rotunda: “I like to call it the state’s living room. You know? It is. It’s a wonderful space, and think about how it’s used. The protest from a few years ago sort of showed how this capitol belongs to everybody in the state. It was kind of cool.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us