Why Wisconsin Schools Teach Native History And Culture

In 1989, a long simmering conflict over American Indian treaty rights helped prompt a landmark educational law in Wisconsin.

By Will Cushman

November 22, 2019

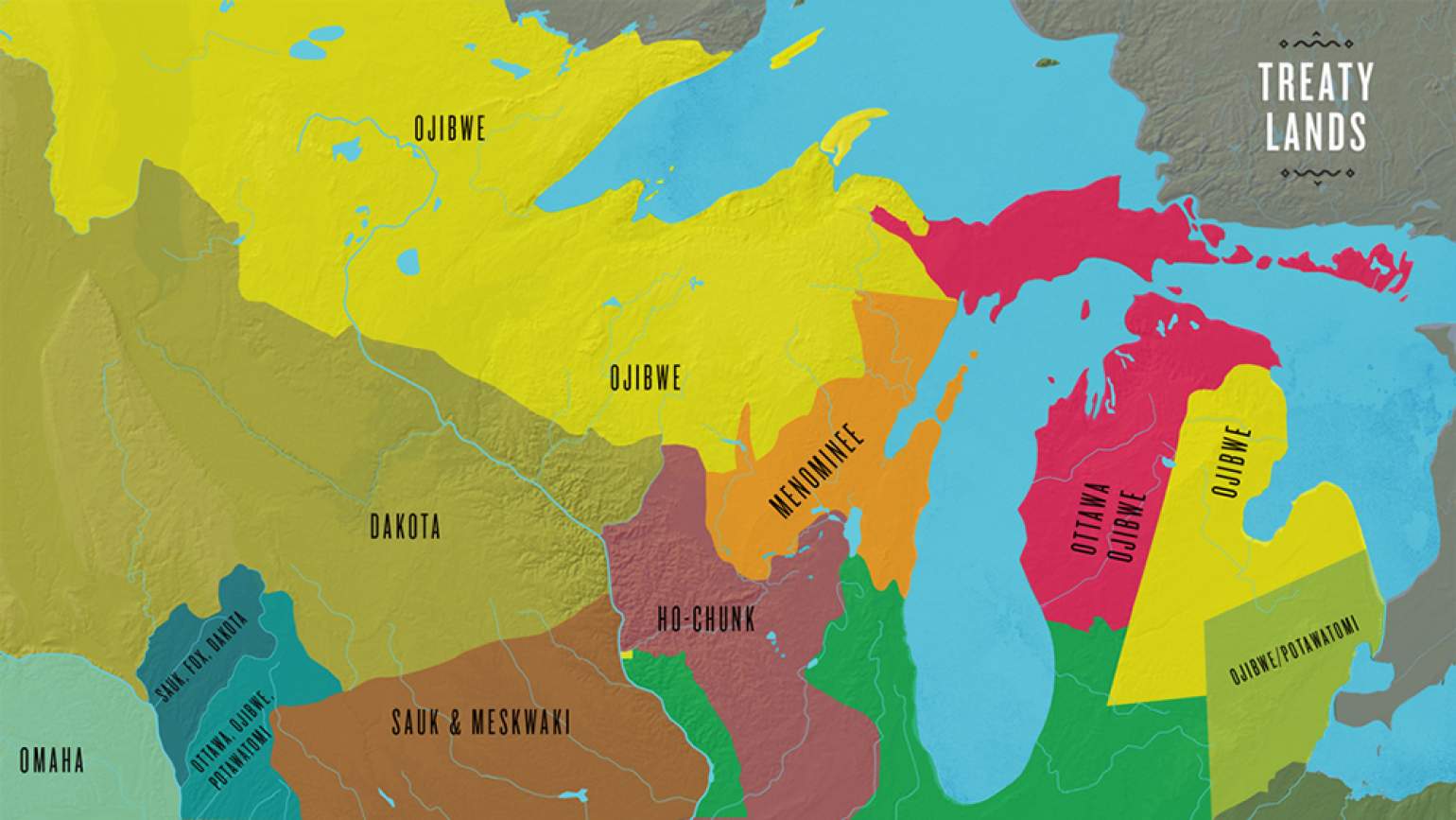

The Ways map of Native American treaty lands in Midwest crop

In 1989, a long simmering conflict over American Indian treaty rights helped prompt a landmark educational law in Wisconsin.

Often called the “Walleye War,” the conflict played out on public boat landings on lakes in the northern part of the state, and drew international attention as white protestors hurled rocks, glass bottles and racist threats at Ojibwe spearfishers. The source of their ire? Federal courts had affirmed the Ojibwe’s right to hunt, fish and gather on the hundreds of thousands of acres within Wisconsin their ancestors had ceded to the United States government in the 19th century.

The 1983 court ruling in Lac Courte Oreilles Band v. Voigt, known as the Voigt Decision, confirmed arguments that state hunting and fishing regulations do not legally apply to Ojibwe tribal members who hold long standing treaty rights to their ancestral lands. In response, some sport anglers, resort owners and others argued the unregulated spearfishing would decimate Wisconsin’s inland fisheries and by extension their hobbies and livelihoods. (It did not.) A couple especially vocal groups organized protests that eventually devolved into the internationally-televised racist violence in 1989.

Many observers blamed the eruption of these protests in part on a general lack of understanding or respect for tribal treaty rights, as well as a long history of racism and cultural subjugation of American Indians, in Wisconsin and elsewhere.

The high-profile nature of the protests and their racist tenor helped propel the Wisconsin Legislature to take what was then an unprecedented step: Mandate specific educational requirements for the state’s schoolchildren, including instruction in elementary and high school about the culture, history and treaty rights of Wisconsin’s 11 federally recognized tribes. The mandate came in the form of five statutes within a 1989 state budget bill known as Act 31.

Since then, the term “Act 31” has become synonymous with American Indian studies in Wisconsin. And though the mandates included in Act 31 became law in Wisconsin during a spike in racial resentment, the events of the 1980s were but one episode in a much longer effort of Wisconsin’s Native peoples to assert treaty rights and stake claim over their cultural history.

J.P. Leary, an associate professor of First Nations studies, history and humanities at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, recounts this story in his 2018 book The Story of Act 31: How Native History Came to Wisconsin Classrooms, published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press. Leary previously served as the American Indian Studies consultant at the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction from 1996 to 2011. He spoke at an Oct. 11, 2018 event spotlighting his book, recorded for PBS Wisconsin’s University Place.

“Part of the popular story [of Act 31] … is that this was related to the treaty rights controversy of the late 1980s and early 1990s in the state of Wisconsin,” Leary said. “Of course it is. But it’s broader than that.”

This broader story includes not only the Ojibwe and their treaty rights to spearfish and hunt, but all of Wisconsin’s Native American communities, as well as the experiences of First Nations across the Americas. It centers on what Leary referred to as “official knowledge” and how it’s shared between communities and through generations.

“That’s the content and the perspectives that become officially validated by our schools,” he said.

For decades leading up to the early 1990s, the historical perspectives taught in Wisconsin’s schools largely erased the region’s American Indians, Leary said, or mischaracterized them as either honorable allies of European settlers or their treacherous foes.

Criticism of how public schools taught Native history was nothing new in the 1980s, Leary reminded his audience. He shared a story about Elmer Davids, Sr., a member of the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians who sat on the band’s historical committee and delivered a speech at the American Indian Chicago Conference in 1961.

“Davids challenged his audience,” according to Leary, “with this pivotal question: ‘Is it fair to the Indian to use the textbooks in our public schools that tend to justify the acts of early settlers and make the poor Indian, resisting in proud self-defense, a culprit and a savage?'”

Nearly 30 years after Davids’ speech in Chicago, Wisconsin leaders decided this portrayal was indeed unfair — and ahistorical.

As an effort to provide new focus on Native history, Act 31 set forth a provision to “include instruction in the history, culture and tribal sovereignty of the federally recognized American Indian tribes and bands located in this state.”

This provision “transformed curriculum policy [in Wisconsin] in unprecedented ways,” Leary said. “‘Include instruction,’ as vague as we might see it now, was incredibly specific — the most specific directive from the state to local school districts.”

While Leary, like many, considers the passage of Act 31 a victory for American Indians in Wisconsin, he said its implementation has been an “ongoing challenge.”

Leary blamed budget and staffing cuts, as well as federal educational policies, for an uneven implementation of Act 31 mandates across the state.

“The law may have provided those eager to offer this instruction with the necessary political power to do so, but there was no viable mechanism to compel instruction where interest was not already present,” Leary said, reading a passage from his book. “Concerns about the adequacy of resources allocated to the Department of Public Instruction to support the requirements arose early and remain a perennial concern to this day.”

Key facts:

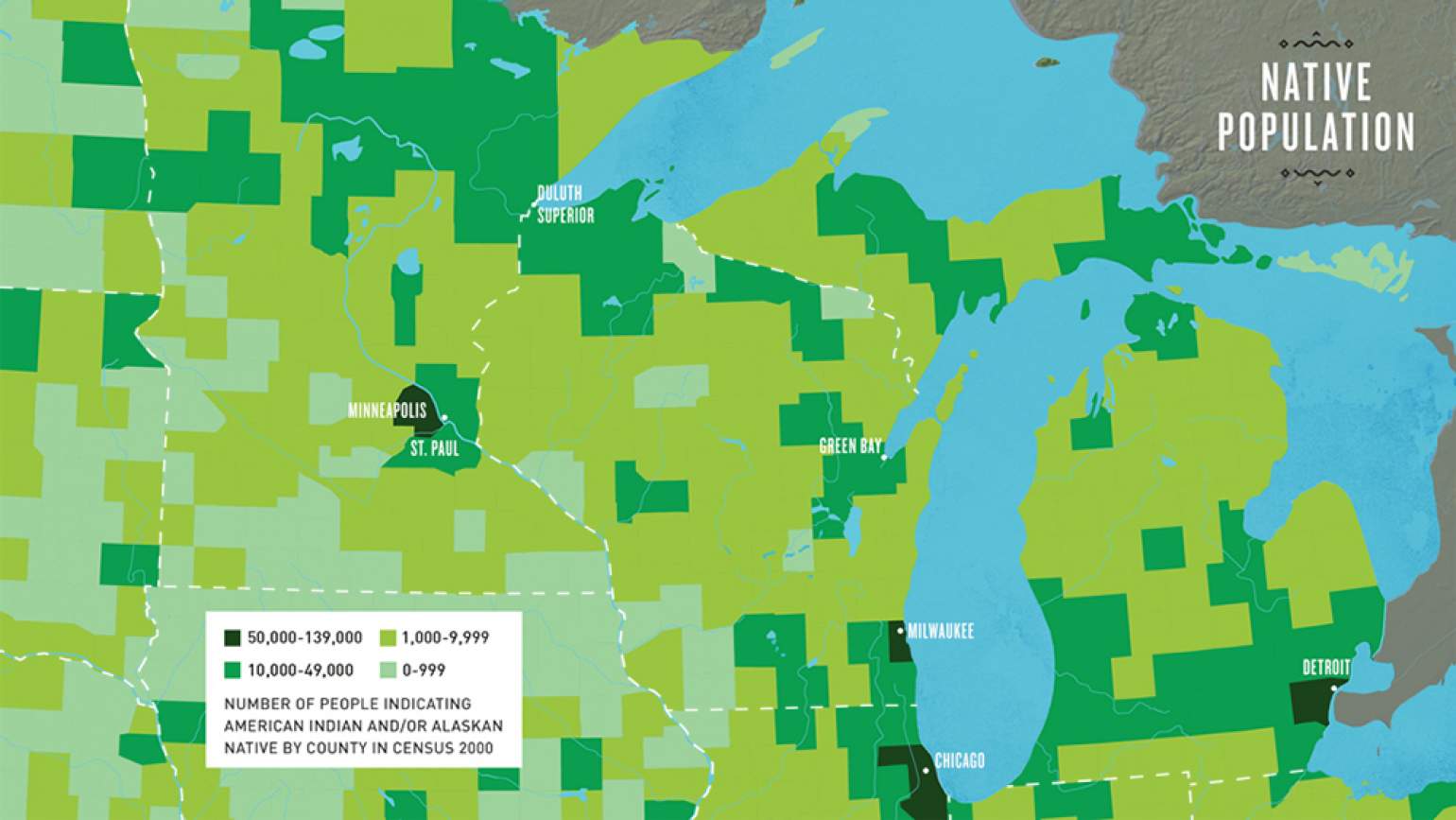

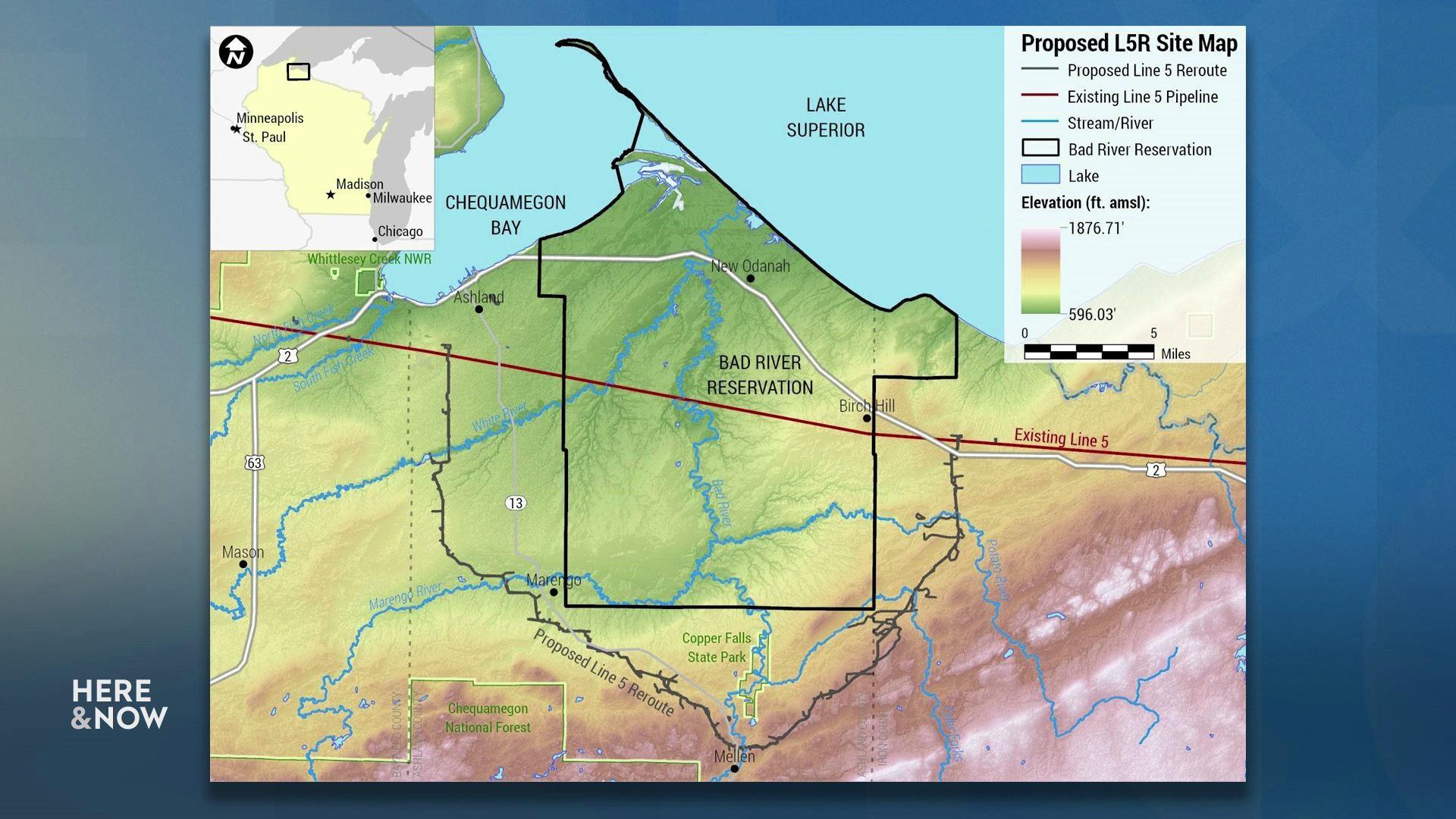

- Wisconsin is home to 11 federally-recognized tribes, out of 573 federally recognized American Indian nations that have a government-to-government relationship with the U.S. federal government. These tribes in Wisconsin are the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Ho-Chunk Nation, Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin, Oneida Nation, Forest County Potawatomi, Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, St. Croix Chippewa, Sokaogon Chippewa (Mole Lake Band of Lake Superior Chippewa) and Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians.

- Wisconsin is home to one tribal nation without federal recognition: the Brothertown Indian Nation. The Brothertown community traces its cultural roots to six parent tribes in New England and has a shared history of migration from the east with members of the Oneida and Stockbridge nations.

- Act 31 was a Wisconsin state budget bill passed in 1989. It included five statutes outlining how the state’s public schools must provide instruction about the culture, history and sovereignty of Wisconsin’s federally recognized American Indian tribes and bands.

- The statutes also mandate cultural training for licensed teachers in Wisconsin, as well as lessons specifically about Ojibwe treaty rights to off-reservation hunting, fishing and gathering and lessons designed to expose students to different value systems and cultures.

- At the time of its passage, Act 31 was the most specific directive from the State of Wisconsin to locally-elected school boards.

- For teachers seeking appropriate curriculum about Native history in the state, PBS Wisconsin Education offers two resources that provide a variety of learning tools. Wisconsin First Nations Education is a partner project that provides educational videos, lesson plans and other materials geared toward pre-Kindergarten through high school students. Additionally, The Ways is an archive of stories about the culture of Native communities in the Great Lakes region.

Key quotes:

- On one of the motivations behind the passage of Act 31: “One of the things that the framers of this particular policy were thinking about is ‘How do we equip our students with the knowledge and skills to live in an increasingly globally connected world?'”

- On the various ways local school boards rely on other entities to make educational decisions: “Even those decisions that are made by a locally-elected school board, those are shaped by forces external to the school district, shaped by things like decisions made by textbook publishers, [decisions] made by curriculum committees working at the state level, working at major professional associations in the national level.”

- On the treaties the Ojibwe bands in Wisconsin agreed to in the 19th century, when they ceded vast territories in northern Wisconsin, as well as Michigan and Minnesota, to the U.S. government: “What we’re talking about in the battle for treaty rights is the reserved rights to hunt, fish and gather within the ceded territory that the six Ojibwe bands in Wisconsin kept for themselves and did not include as part of a broader real estate transaction.”

- On the late 1980s protests in Wisconsin against tribal members exercising their treaty rights and how they relate to the passage of Act 31: “It’s really no accident that Act 31 was passed in 1989 because that was the year that the protests were the most violent. It was in that spring that there was a legitimate concern that someone would be killed at a Wisconsin boat landing.”

- On a belief that racism toward Native Americans in the wake of these disputes was limited to only some parts of the state: “The popular understanding is, ‘Oh, it’s those folks up north, right? It’s them up there.’ And it didn’t matter if I was in Madison, Milwaukee, Eagle River, Fennimore, it didn’t matter where I was. These kinds of things were all across the state. And so, passing the buck to ‘them, up there’ is simply not accurate.”

- On the discrepancy between Act 31’s vision at the time of its passage and what has followed: “That victory story, that story of such hope in 1989 … has not borne out.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us