Why Winter Is A Good Time To Track Wisconsin's Wolf Packs

As wolves returned to broad swaths of Wisconsin after decades of being extirpated from the state, a tracking program in which volunteers scout for the presence of this predator grew, too.

February 22, 2019

Wolf in field in Jackson County 2

As wolves returned to broad swaths of Wisconsin after decades of being extirpated from the state, a tracking program in which volunteers scout for the presence of this predator grew, too.

Since 1978, when the gray wolf (Canis lupus) was identified in Douglas County, the first sighting there in about two decades, the animal’s population across the state sharply increased. By the winter of 2017-2018, the minimum number of wolves in the state stood between 905 and 944, based on the annual count by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

Keeping track of the growth and spread of wolves in Wisconsin became more difficult and required help beyond the capacity of the DNR. That need spurred creation of its volunteer tracking program that’s been active since the 1990s, said Nathan Kluge, a DNR wolf biologist and coordinator of this monitoring effort.

“It is absolutely critical and the biggest factor that determines our minimum count,” Kluge said of the volunteers. “We would not at all be able to get even close to counting the wolves in Wisconsin without the number of volunteers and the coordination that we have, and the participation from volunteers that we have.”

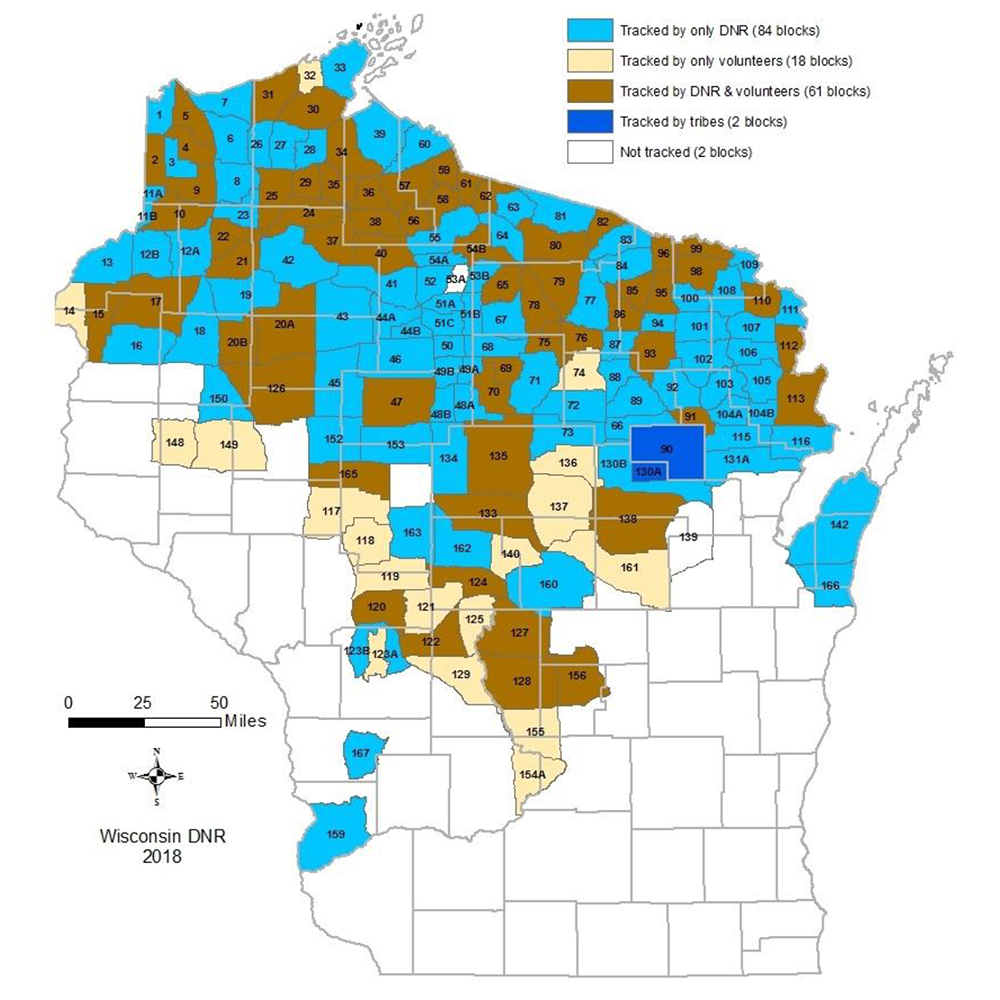

Volunteer wolf trackers now number more than 130 strong, and they’re managed by 12 regional coordinators. In 2018, these surveyors had a hand in tracking wolves in nearly 80 of the DNR’s 168 survey blocks in northern, central and east-central Wisconsin.

One of those coordinators is Eau Claire resident Linda Nelson, who has been a volunteer tracker since 1997. In her position, she oversees about 30 volunteers in 39 blocks.

Blocks are areas averaging about 207 square miles that are set up by the DNR and surveyed by staff and volunteers. They’re places where wolves and other carnivores have been observed or followed via 50 animals mounted with radio collars.

Kluge said surveys aren’t really conducted in southern Wisconsin because the abundance of farm fields and people make those areas less appealing to wolves.

When Nelson first began scanning parts of Eau Claire and Clark counties more than 20 years ago, she found evidence of one possible pack. Now, she is seeing five or six different packs inside of one block.

Volunteers are assigned to at least one of the survey blocks, which are outlined with landscape features that help the surveyors to know where the boundaries are, said Scott Walter, a large carnivore specialist with the DNR.

Some blocks are more densely packed with wolves than others, especially in the Central Forest region where Nelson surveys, Kluge said. That’s because there are abundant resources there and limited human interaction.

In the 2017-2018 count, 238 wolf packs were found across 167 tracking blocks. Wolves tend to establish territories that are about 53 square miles, Kluge explained.

A common practice for the volunteer surveyors is to first identify forest roads in their survey blocks. Volunteers drive along roads at speeds of 10 miles per hour or slower for about 20 to 30 miles, looking for signs of wolves.

Throughout one winter, one block will be surveyed three separate times, Walter said.

Keeping eyes and ears peeled

Wolf counts in Wisconsin start in the winter since snow can provide good impressions of wolf tracks.

Wolf tracks are the primary identifier that surveyors rely on, but they can be tricky too, because they resemble prints from other members of canid family, such as dogs, red or gray foxes, and coyotes.

There are noticeable differences between the tracks, though, and size is one of the determining factors, said DNR biologist Scott Walter. Still, the paws of large breeds of dogs could easily be confused for those of wolves.

That’s when trackers pay closer attention to the toes. The outer toes of dogs tend to be splayed outward. Their chests are broader and so are their straddles. The front wolf tracks appear to have a narrower straddle, meaning there’s less space between the front paw imprints.

“All these little details when you get out there to track are important to know,” he said.

Figuring out the species that left prints is one matter. Another is distinguishing between individual wolves in a pack, which can be complicated by deep snow.

In northern Wisconsin, when snow depth reaches 30 inches, it’s higher than the chest of a wolf, explained DNR biologist Nathan Kluge. In these cases, wolves are more likely to walk in each other’s tracks.

Volunteer wolf tracker Linda Nelson said it’s all about strategy to spot tracks.

“You’ve got to try and find a split, you’ve got to try to find a break, that tells you how many different animals there are,” she said. “I have my best luck when animals are coming out of the woods and onto the roadside.”

Along with counting tracks, surveyors also are watching for evidence of raised leg urination, which is employed only by the dominant males and females. All other members of the pack squat to relieve themselves.

Another important sign provided by raised leg urinations is the presence of blood in the urine, which indicates the female is receptive to breeding.

When volunteers identify active wolf areas, the DNR has a better idea of where to return in the summer to conduct howling surveys to determine whether breeding was successful in the spring.

Females on average have four to six pups each year, and even though only about 30 percent of the pups born live beyond their first year, those numbers still impact the wolf count.

Howl surveys are another component of the DNR’s broader wolf monitoring efforts to achieve an accurate wolf count.

Because pups aren’t born yet when winter surveys are conducted, volunteers and DNR staff will head back out during summertime to areas where raised-leg urinations with blood were documented during the winter.

Howl surveys are conducted during the summer because wolf packs tend to stay closer together as the adults raise their young. Volunteers will howl, and document the responses they hear. Pups will yip excitedly in contrast to adults.

Other data taken into consideration to complete the wolf landscape picture are trail camera photos and mortality numbers, which can impact final counts because each adult has a 70 percent chance of making it through the year.

Before volunteers can conduct surveys on behalf of the DNR, they’re required to take a DNR-approved training course. These classes help spotters understand a wolf’s behavior and ecological niche and teach them how to properly identify wolf prints.

Even before they arrive for training, though, volunteers are well on their way, Walter said.

“They’ve got the main tools needed — that’s interest and enthusiasm,” he said.

Steeped in these traits, volunteers such as Nelson leave a lasting impression on the work of the program.

“I credit the longevity of some of these people and some of the new people that step in — everyone just offers so much, and it really helps out,” Nelson said.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us