Why Wasn't 2018 A Big Election For Women In The Wisconsin Legislature?

Women vying for public office made historic waves across the United States in the 2018 midterm elections. Wisconsin, however, didn't quite follow that national trend.

January 7, 2019

Wisconsin Senate chamber facing dais

Women vying for public office made historic waves across the United States in the 2018 midterm elections. Wisconsin, however, didn’t quite follow that national trend. Additionally, while voters elected more women to the state Assembly in 2018, the state finds itself lagging behind its Midwest neighbors.

More than a few national political observers hailed 2018 as another “Year of the Woman” following a previous declaration about the 1992 elections. While it may be simple to make such generalizations in national terms, determining how women fare in state-level elections is a different story.

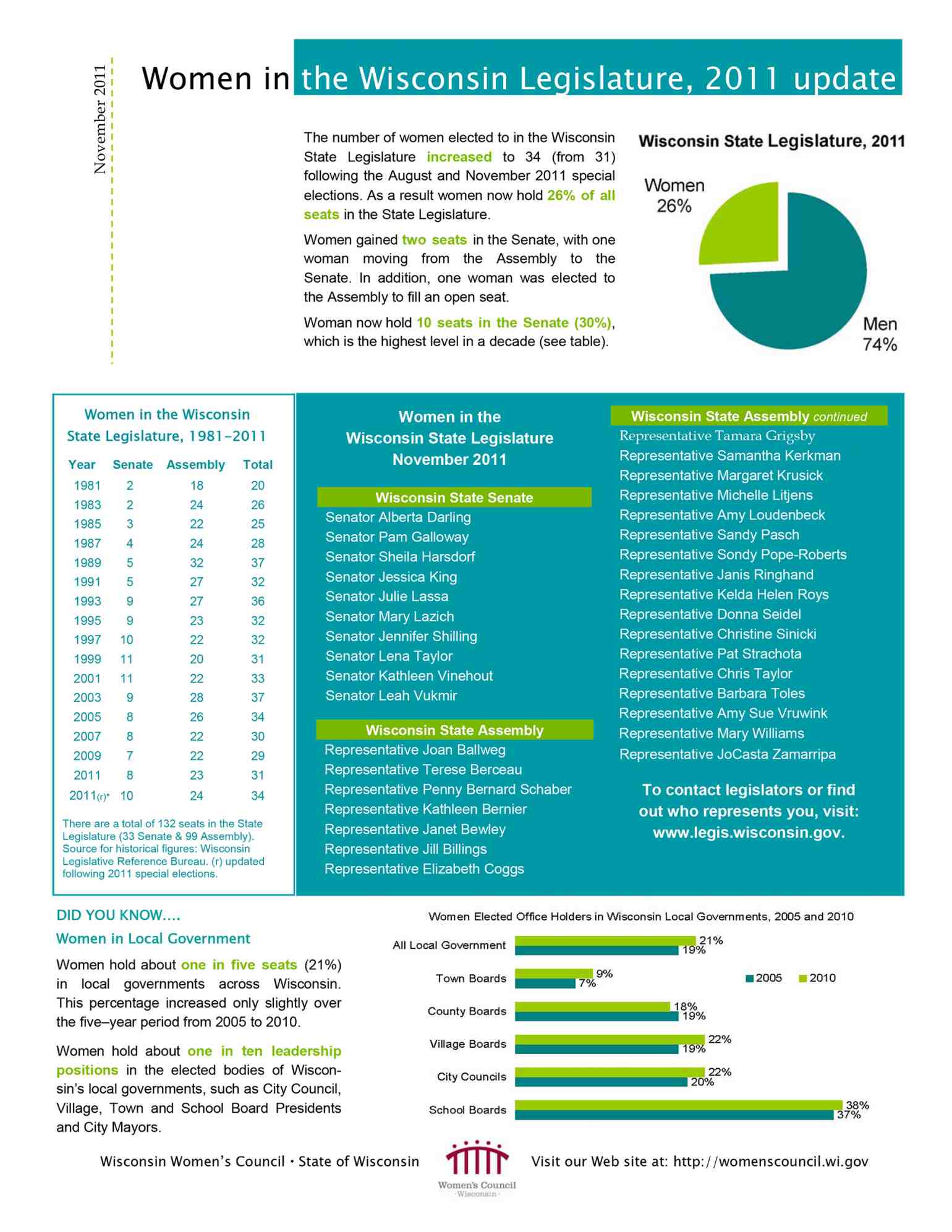

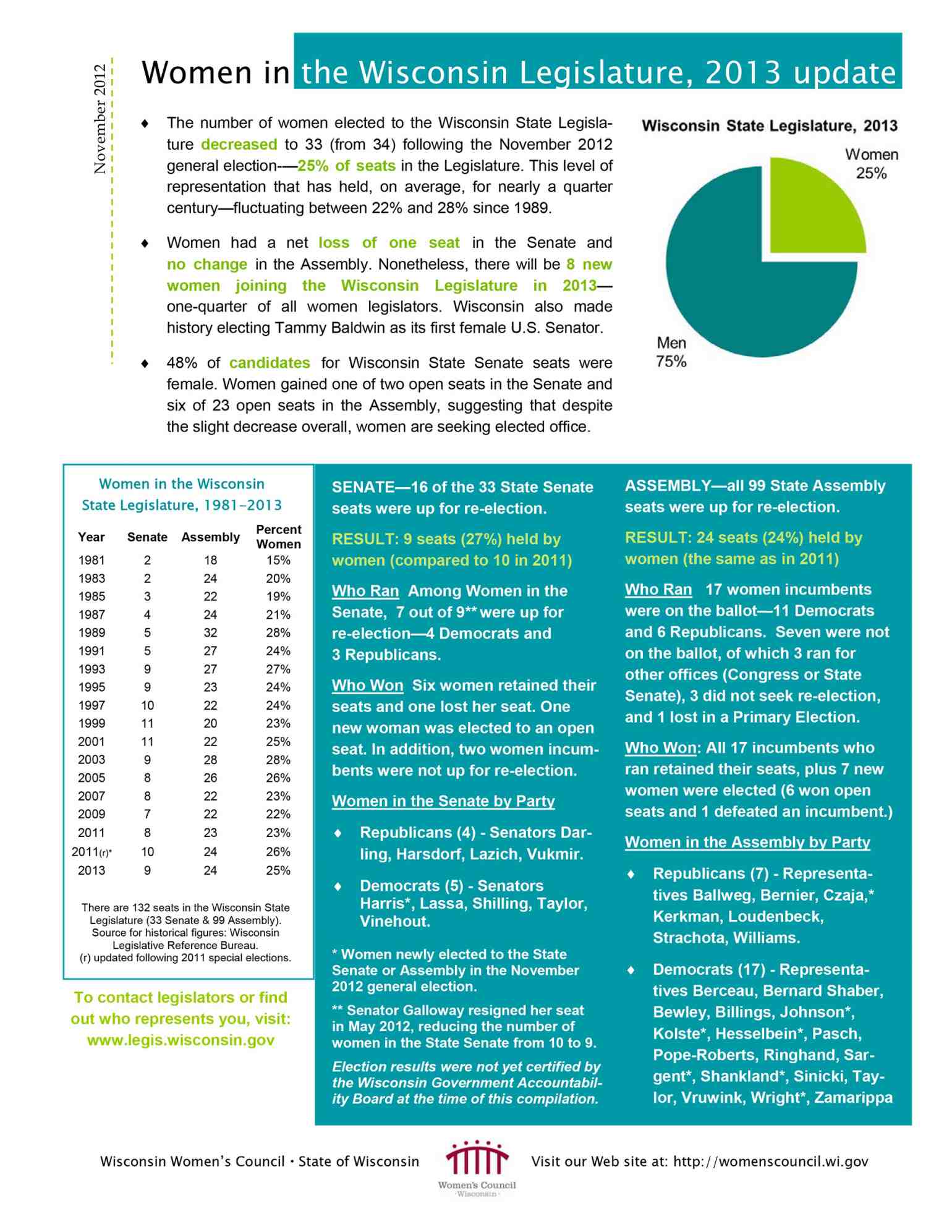

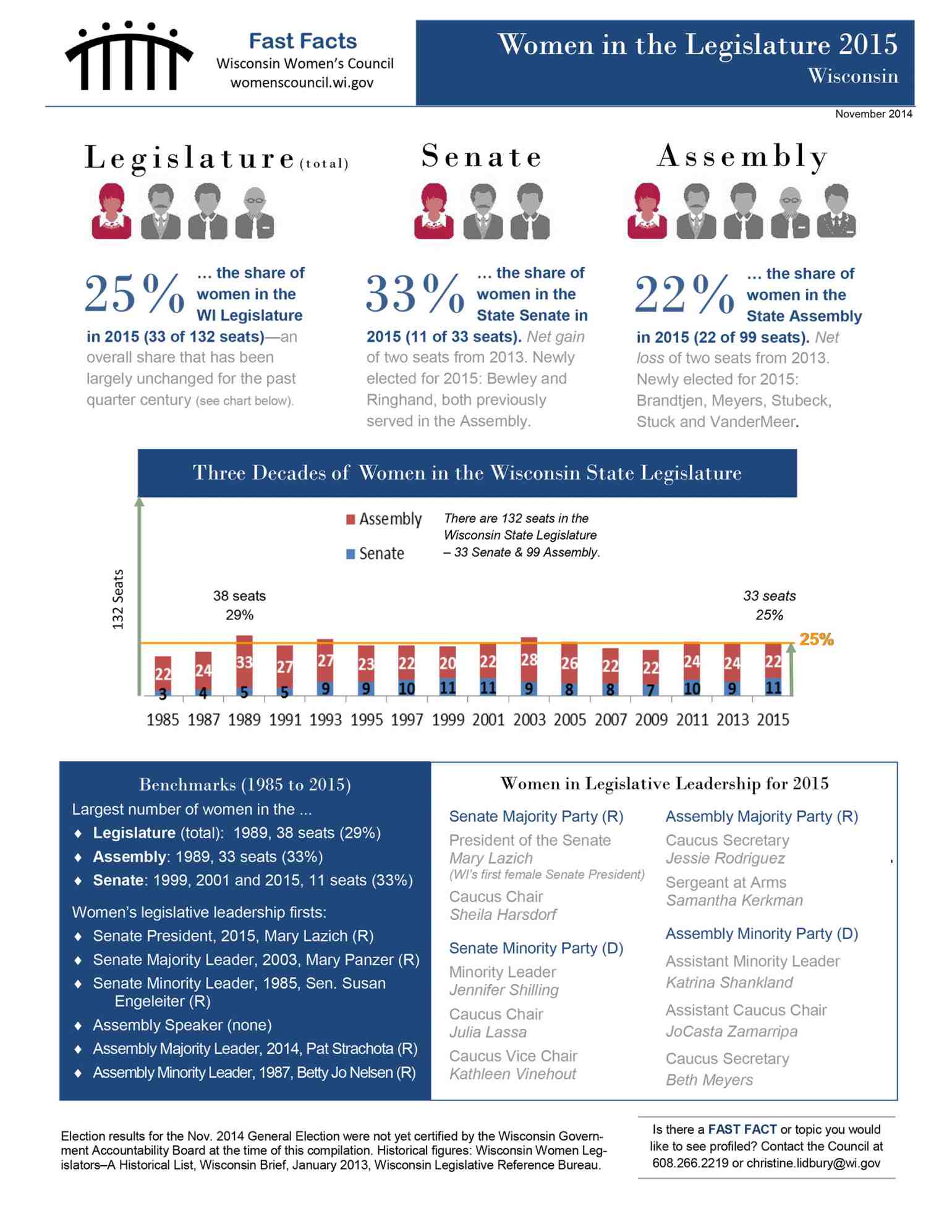

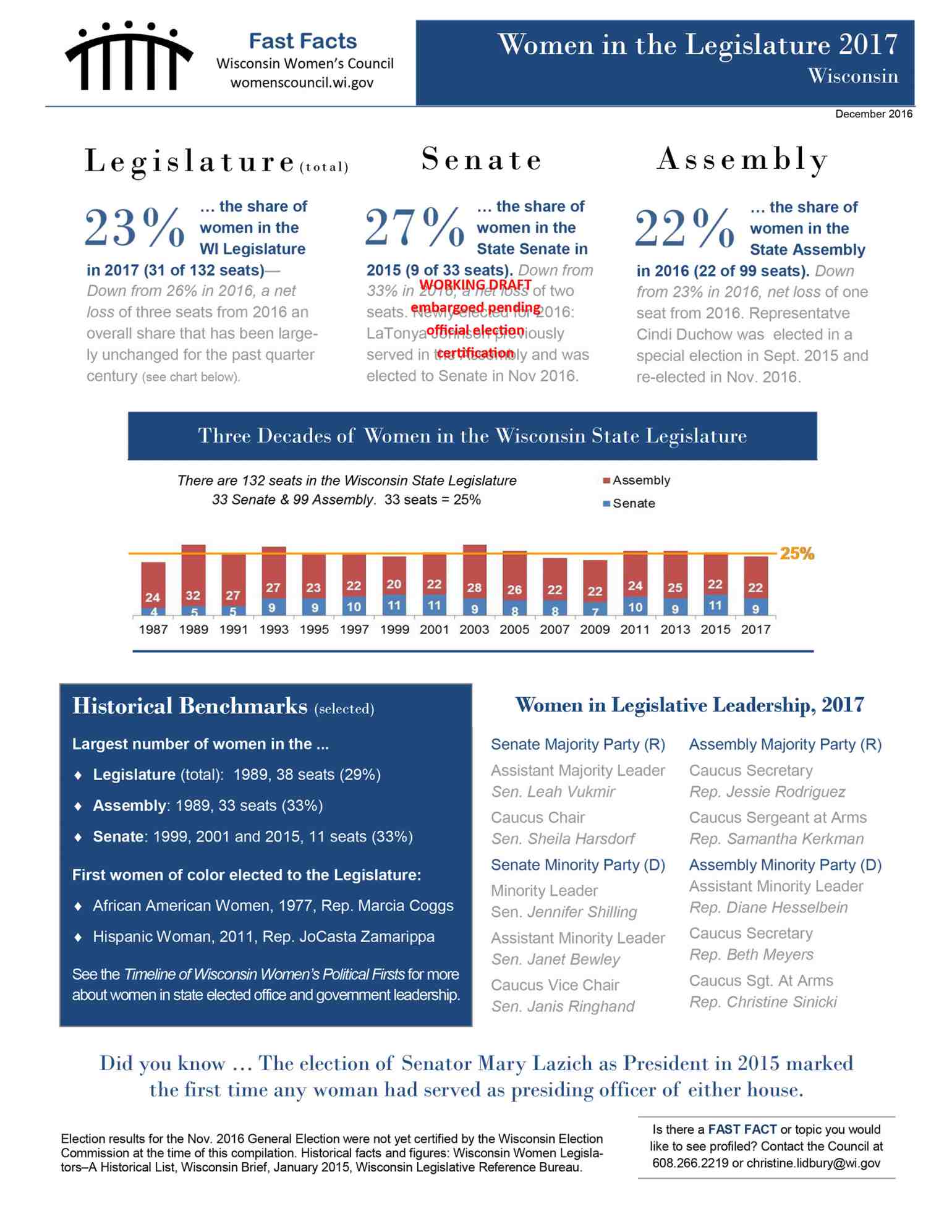

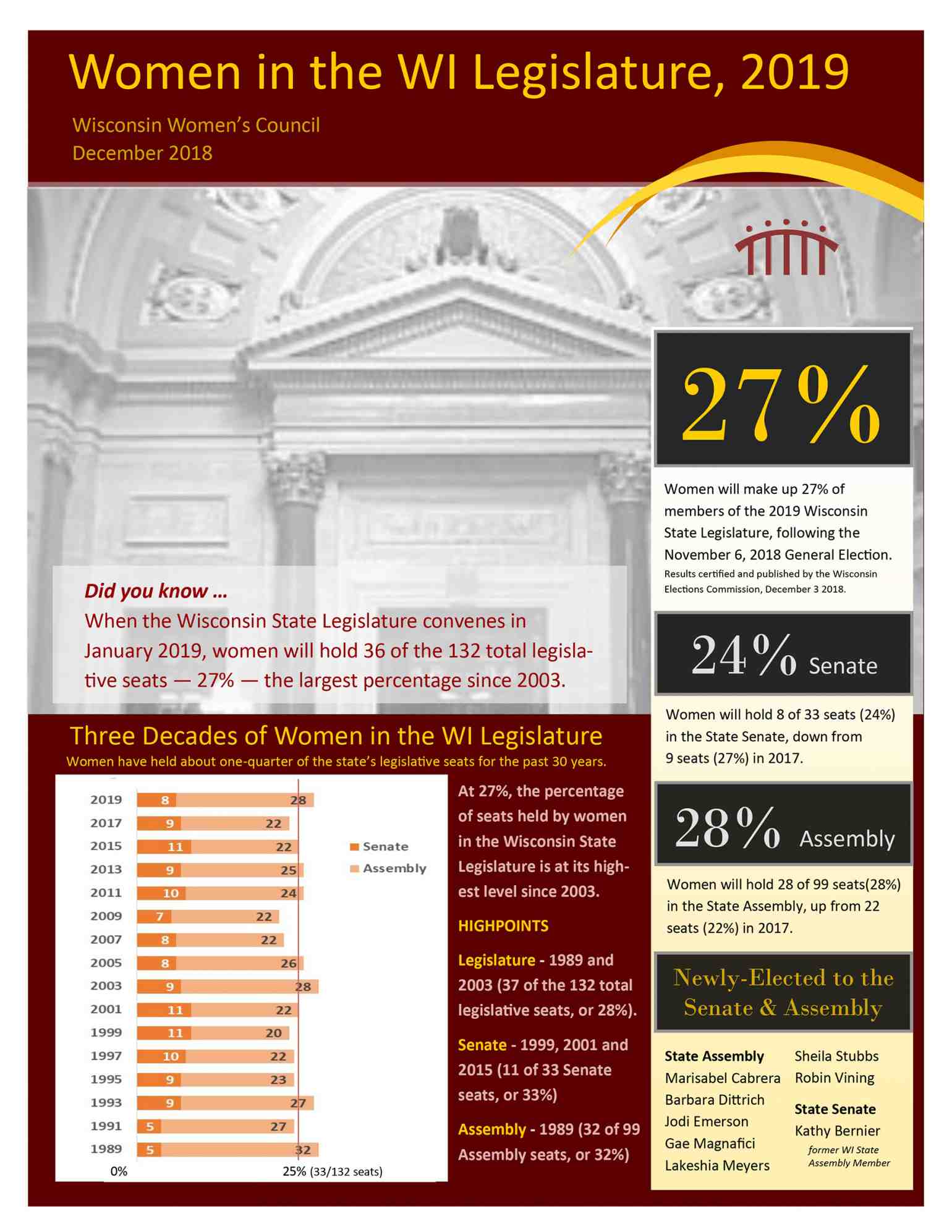

Over the past three decades in Wisconsin, the number of women in each legislative class has been on average about one-quarter overall. The sessions with the most women were 1989-1990 and 2003-2004, each reaching 28 percent. The state’s incoming 2019-2020 class fell just short of reaching that mark with 27 percent women, according to an analysis by the Wisconsin Women’s Council. A state agency aimed to promote and enhance the well-being of women, the 15-member council is appointed by the governor and the Legislature’s leadership, and consists of both public and legislative members.

A WisContext analysis of election records found, compared to its neighboring states of Illinois, Iowa, Michigan and Minnesota, Wisconsin has the lowest percentage of women serving in its Legislature. However, all five states have a long way to go before any reaches parity in the number of women and men running for office.

These five Midwestern state legislatures are not equal in size, which means that differences in the number of women running for seats are not as meaningful as differences in the percent of women running. Of these five states, Minnesota has the largest statehouse with 201 seats in its two legislative chambers. Illinois, Iowa and Michigan follow with 177, 150 and 148 seats, respectively. Wisconsin has the smallest number with 132 seats total. Additionally, not all seats in these state legislatures were up for election in 2018, except in Michigan. In Minnesota, only seats in its House of Representatives were up for election, while in Illinois, Iowa and Wisconsin, some state senate seats were not.

When it comes to where women won big in 2018, Michigan came out on top percentagewise — women make up 36 percent of its newly elected state legislators. Not far behind is Illinois, at 32 percent. Iowa follows with 27 percent, while Minnesota and Wisconsin come in last at 24 and 23 percent, respectively. In Wisconsin, counting five state senators not up election in 2018, the total percentage of women serving in its Legislature in the 2019-2020 session is 27 percent.

The national average of women in state legislatures is 28.6 percent, according to a count by the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers.

To determine these numbers, WisContext collected data from the state agencies responsible for elections in each and tallied the women candidates. For this analysis, WisContext looked at women candidates running as Democrats or Republicans in state legislative races in 2018. This is not to say women didn’t run as third party candidates — many did. However, a closer look at Democratic and Republican candidates highlights the emerging partisan dynamics of women running for office.

A partisan divergence

Wisconsin’s 2019-20 legislative class will have a handful more women than its predecessor, but it doesn’t break a pattern of stagnation in place over the last 30 years.

Through the 1980s, women held about one-fifth of the state Legislature’s total seats, preceding a jump in the 1988 election. Since that time, the percentage of women officeholders has hovered around the 25 percent level, give or take a few seats.

During the ’80s, the difference in the number of women legislators who were Republicans and Democrats wasn’t big, said University of Wisconsin-Madison political science professor Barry Burden, who serves as director of the Elections Research Center. However, a partisan difference began to emerge after the first so-called “Year of the Woman” in 1992. Since then, women in the state Legislature have increasingly been Democrats.

Half of the incoming class of Democratic representatives in the Wisconsin Assembly will be women, with their ranks in the state Senate reaching 43 percent, Democratic Party of Wisconsin spokesperson Courtney Beyer noted in an email to WisContext.

Beyer argued that gender disparity in the state Legislature is due to Republican positions and policy, saying that party’s values do not align with those held by many women.

“It might explain why only [two of 19] Republican Senators in the next session will be women … and why every poll shows Republicans are losing suburban women,” she continued.

There is a well-documented gender gap in partisan voting patterns. National data shows a majority of women voted for Democrats in 2018, and trends indicate this gap is likely to continue to grow. The number of Republican women candidates elected to Congress dropped in 2018, adding to an ongoing partisan gender disparity in representation at federal and state levels.

The Republican Party of Wisconsin did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

A number Republican women have run for and won high profile races in Wisconsin in recent years. Rebecca Kleefisch served as lieutenant governor alongside Scott Walker, and Leah Vukmir ran for U.S. Senate in 2018 against the Democratic incumbent Tammy Baldwin.

Women running in any party face many challenges when it comes to winning elections. Among these difficulties, as outlined by UW-Extension educators, are a lack of confidence and time, as well as the demands of fundraising. All can pose barriers to women considering a run for office.

But with the act of just running a campaign, women can inspire future female candidates, said Emerge Wisconsin executive director Erin Forrest. That’s exactly a goal Emerge has for politically left-leaning Wisconsin women.

“When women run for office, more women run next time,” she said. “Win or lose.”

Founded nationally in 2002 and in Wisconsin in 2006, Emerge has launched hundreds of women into local and statewide offices, Forrest said. One example on the 2018 ballot was Sarah Godlewski, who won her campaign for state treasurer.

There’s no conservative equivalent to Emerge in the state, which Forrest said adds to the disparity between men and women in elected office.

“We’re not going to get to parity if Republican women don’t run for office,” she said.

The role of gerrymandering

UW political scientist Barry Burden said the pattern of stagnation for women in the Wisconsin Legislature has been masked by other political trends. One critical factor is the effect of partisan gerrymandering in the state.

Burden said if Democrats had maintained control of the Legislature after the 2010 elections, Wisconsin would be far more likely to have more women in office. But since Republicans gained control and redrew election maps in 2011, a time when women running as Democrats were making gains in other states, Wisconsin’s numbers remained level, he explained.

In Wisconsin’s 2018 midterms, 12 women ran as Republicans for a seat in the state Legislature. That figure compares to 51 women who ran as Democrats for the same set of offices. This partisan divergence proved to be a trend, at varying levels, among Wisconsin’s neighbors.

While many more women ran as Democrats than Republicans in Illinois, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin in 2018, it didn’t necessarily translate to major Democratic gains in the five state legislatures.

Of the 51 women who ran as Democrats in the 2018 Wisconsin midterm elections, only 20 won their races, compared to 11 out of 12 wins for women running as Republicans. On the whole, Democrats only picked up one seat in the Legislature.

Emerge Wisconsin’s Erin Forrest blamed this difference on the state’s Republican-drawn district maps.

“Women are far more likely to run for office as Democrats and win office as Democrats. So when these maps are rigged against Democrats, they’re also rigged against women,” she said.

Michigan, which has been cited as one of the most gerrymandered states in the U.S., also saw a large disparity between the number of Democratic women candidates who ran and those who won in 2018. However, an even smaller percentage of women running as Republicans won their races.

In Illinois, where election maps were drawn by Democrats, women made larger gains, primarily running as Democrats.

In Minnesota, which was redistricted in 2011 through a bipartisan process that involved the courts, Democrats were able to flip 18 House districts in the Twin Cities suburbs, the Pioneer Press reported. Victories among Democratic women accounted for 11 of the flipped districts.

Iowa is the one state in this group where election results cannot be attributed at all to gerrymandering. Since 1980, Iowa’s districts for state legislative and congressional seats have been drawn by the nonpartisan Legislative Services Agency. As a result, the differences between of Democratic and Republican women candidates who won was much less drastic, though there was still an overall disparity between the parties.

Women ran, but did they win?

While gerrymandering is an important factor at play in election results, there are many others to consider as well, said UW’s Barry Burden. One is simply the tendency of voters to keep incumbents in office. A lack of turnover can become a great barrier for potential female politicians to overcome.

“There needs to be turnover to help accelerate the number of women in office,” Burden said. “When incumbents continue to win and incumbents continue to be male, it will be harder for women to make gains. The fact that so many incumbents will be returning … I think puts a limit on how fast women can make gains in the Legislature.”

Burden also noted that Democratic candidates face another disadvantage related to the distribution of legislative districts because of a concentration of their voters in more densely populated areas. On the other hand, Republican voters tend to be more evenly distributed across suburbs and rural communities. This pattern, he said, would make it nearly impossible for Wisconsin Democrats, if they had the means and inclination, to draw an election map that would give them an advantage.

“Just about any map that would be created — even one that Democrats create — is probably going to give Republicans some advantage or head start,” he said. “It’s very difficult to spread out Democratic voters across enough districts to give them a shot at winning proportional to their vote totals in the entire state.”

Given the partisan gender gap in voters and candidates, electing women at the state level has continued to prove itself to be a confounding issue, Burden said. There’s yet to be one magic approach that would bring more women from both major parties (or others) into office.

“There is something different happening at the state level,” he said. “In Congress, in both the House and the Senate, and governorships, women have made slow progress in representation over time. But the state Legislature just does not happen in the same degree.”

Editor’s note: This article was updated with additional information about the number of state legislature seats in Iowa, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin up for election in November 2018.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us