Why more local pharmacies are struggling to stay in business

Rx Uncovered: Drugstores across the United States continue to close, and these businesses point to pharmacy benefit managers as a culprit — proposed legislation in Wisconsin aims to limit their scope.

By Marisa Wojcik | Here & Now

July 25, 2025

Drugstores continue to close, and they point to pharmacy benefit managers as a culprit.

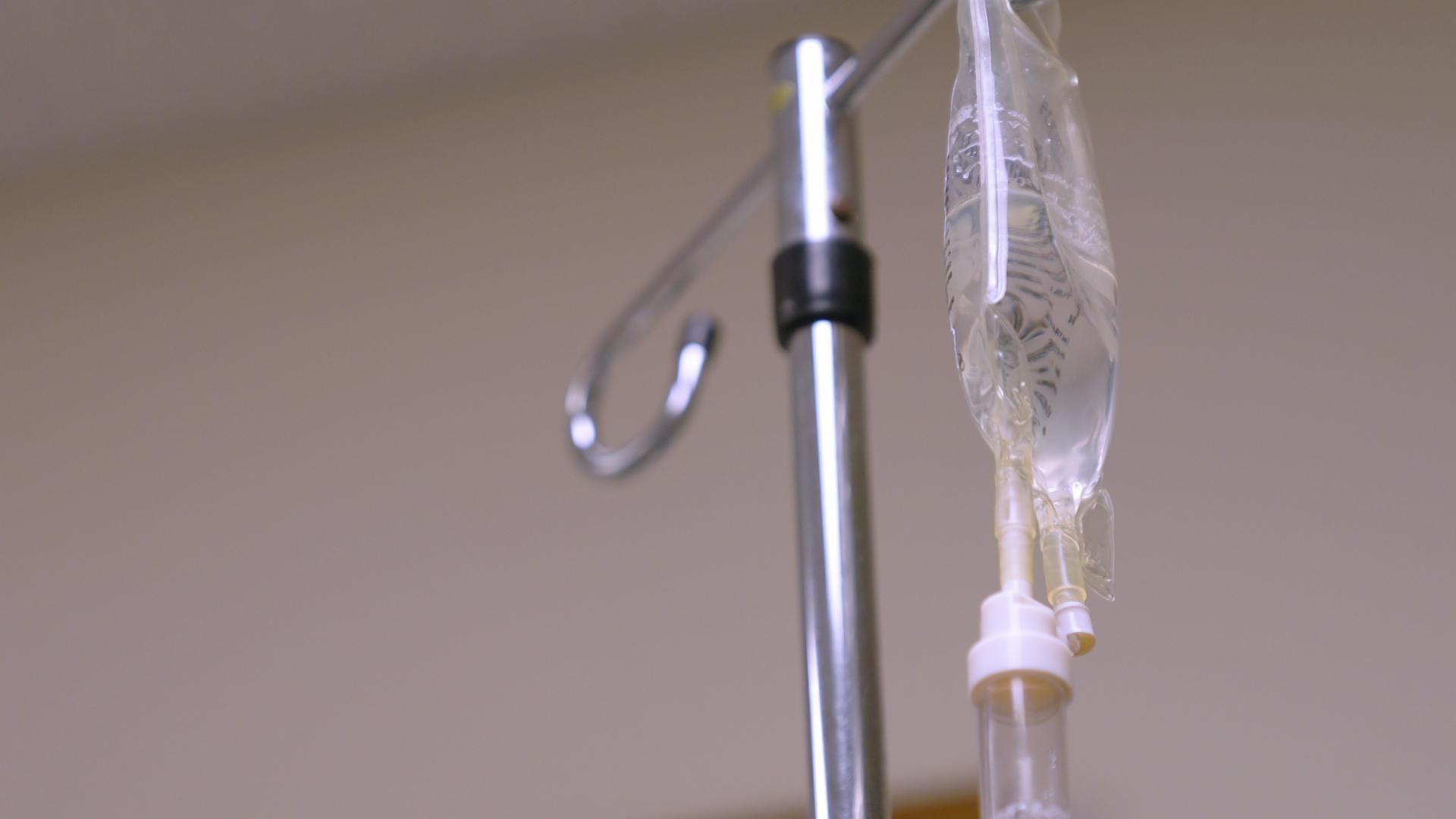

For decades, the cost of prescription medications has been ever increasing. At the same time, health coverage of these medications has been decreasing, forcing patients to make harder decisions about their health. Rx Uncovered is a series from “Here & Now” producer Marisa Wojcik that dives into the complex systems driving these trends and the stories of patients facing life or death choices. The third story is about impacts on pharmacies both big and especially small, and why their disappearance is hurting patients.

“We have been in business for over 70 years,” said Nicole Schreiner, “and we look at our financials every month, and it’s scary. And we think about how long can we last.”

The local drugstore was, once upon a time, a staple in communities across the country.Today, whether it’s the local drugstore or a chain pharmacy, the brick-and-mortar presence is dying.

“The feasibility of having an independent pharmacy is becoming very challenging,” said Schreiner, who is CEO of Streu’s Pharmacy Bay Natural in Green Bay, and president-elect of the Pharmacy Society of Wisconsin.

“We get up in the morning because we want to truly help serve our patient,” she said.

Alongside this commitment to the mission, Schreiner takes on her new dual roles in one of the most challenging times for pharmacies. From 2010 to 2021, 30% of drugstores in the U.S. closed. In 2024 alone, about 2,300 pharmacies closed, half of them being independent or mid-sized businesses.

“It’s creating an access issue for patients,” explained Schreiner. “We oftentimes talk about, in rural areas, patients having to travel perhaps 20 miles to find a pharmacy that would be able to provide their medications. But we’re having that even in urban city areas.”

For some, a visit to the pharmacy is a quick stop, picking up one or two prescriptions. But for many patients, it’s much more than that.

“Your pharmacist a lot of times will be a critical component of your medical care team, said

Wisconsin Senate President Mary Felzkowski, R-Tomahawk, who authored legislation trying to help local pharmacies keep their doors open.

“The first way that I literally became involved in this is we saw our small independent pharmacy starting to go out of business in rural Wisconsin,” she said.

When it may take months for a patient to get a clinic visit, pharmacists say they bridge that gap, available for anyone to walk in and ask questions at any time. And prevention leads to health care savings.

“For patients with asthma, we did a study with the Pharmacy Society of Wisconsin and showed that when they sat down with the pharmacist on two 30-minute interventions, that they reduce the number of ER visits, the number of hospitalizations. These things are making a difference in overall reducing health care dollars spent, she said.

Like with most retail stores, it would be reasonable to assume that internet sales put pharmacies out of business. And while mail-order and online retailer giants like Amazon do compete with on-site service, advocates diagnose a much deeper and chronic issue.

“Pharmacy benefit managers have been around for a very long time,” noted Felzkowski.

Pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs, act as middlemen between drug manufacturers, wholesalers, providers, insurance companies and pharmacies.

“They have monopolized, and they’ve gotten in between prescribers and the delivery of drugs,” Felzkowski added.

The three largest PBM companies accounted for 80% of prescription claims in 2025.

“They’ll claim that they negotiate with drug manufacturers and pharmacies to reduce overall prescription drug costs. However, despite these claims, PBMs regularly inflate what patients pay and force pharmacies to operate at a loss,” said Ben Pearlman, director of state government affairs at the National Association of Chain Drug Stores.

“It’s become very powerful, and independent pharmacies like myself have no negotiating power anymore with these PBMs,” Schreiner said.

“The impact that PBMs are having on rural pharmacies is staggering,” said Bob Jaskolski, president and CEO of T.A. Solberg Co., Inc., which owns grocery stores and other businesses in northern Wisconsin.

The legislation takes aim at a number of their practices, including not allowing patients to fill prescriptions at certain pharmacies, punitive audits against pharmacists who inform patients of lower-cost options, and perhaps the biggest of all for pharmacies, reimbursing the price of medications below cost.

“PBMs dictate where prescriptions can be filled, what to charge a patient” said Jaskolski, “what they will reimburse the pharmacy, and when they’ll pay the pharmacy.”

Those practices force pharmacies to take losses.

At a Wisconsin Senate Committee on Health hearing on May 28, numerous local pharmacies attested to this issue.

“My pharmacy is currently operating in the red right now, solely due to PBM reimbursement rates,” said Nic Smith, a pharmacist and owner of Smith Pharmacy in Little Chute.

“Margins estimated to PBMs have increased by 46%, and during the same time, margins to pharmacies have decreased by 47%,” said Larry Crowley, a pharmacist at Hometown Pharmacy in Dodgeville.

“The contracts have become basically take it or leave it,” Schreiner said. “They’ve continued to erode year after year after year, and it’s estimated that independent pharmacies, depending on your particular location in the country, can have anywhere from 20% to 40% of their claims actually reimbursed below cost.”

But not all health industry experts agree.

“We believe all these provisions will be associated with increased costs to health plans and sponsors,” said Abbey Rude, a lobbyist with the Madison-based Alliance of Health Insurers.

Those in opposition to the bill, such as health insurers, say it will increase prices for health plans, employers and patients. The exorbitant cost of drugs, they say, begins with the drug manufacturers.

“Instead of taking away the few tools that health plans and employers use to address ever-increasing drug prices, the Legislature should focus on fixing the market distortion caused by drug manufacturer pricing schemes,” said Patrick Lobejko, a regional lobbyist with the Washington, D.C. firm America’s Health Insurance Plans.

“Some of our employer groups do not agree with portions of that,” Felzkowski said, “and we’re going to work very hard on showing them through data from other states that have allowed that — have the same legislation — where it’s actually lowered the cost of health care.”

Whatever the cause, the impact on the patient is real, like the ability to obtain diabetes medications.

“GLP-1s: Some pharmacies are just choosing not to carry them because they get reimbursed below their cost,” Schreiner noted.

Or having your insurance accepted.

“Some pharmacies are choosing not to carry particular plans because of the poor reimbursement,” she added.

“Every day in my pharmacy, I witness patients facing exorbitant co-pays, sometimes exceeding $500 for medications they cannot afford. These patients are confused, they’re overwhelmed, and they’re forced into impossible decisions about their health,” Crowley said.

For a patient having to fill prescriptions at multiple pharmacies, the consequences can cost them their lives.

“Recently, when interviewing a patient, we learned that they had a duplicate prescription that was at another pharmacy from a different doctor. If they had gone home and taken both, they would have needed emergency care and it could have been fatal,” said Josie French, director of pharmacy with Trig’s grocery stores in northern Wisconsin.

Independent pharmacists say from the COVID-19 pandemic to the work they do every day, their commitment is to their community.

“What happens if PBMs continue to drive us out of business? Who will step up during this crisis? Who’s going to be doing seven-day-a-week testing? Who’s going to deliver meds late at night for a hospice patient? Who’s getting a call at 2 a.m.? I just got that last week. It won’t be a mail order pharmacy in another state that’s doing that. I guarantee you that,” Smith said.

“Being able to provide that service to patients,” said Schreiner, “and to be part of making sure that they are taken care of is really what we want to ultimately do.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us