Why Immigrant Workers Became The Backbone Of Wisconsin's Dairy Business

Immigration as a top line issue for dairy farmers would have been unthinkable just a generation ago when Wisconsin's agricultural landscape was dominated by small and medium-sized dairy farms run by the families that owned them.

October 5, 2017

Immigrant worker in milking parlor at Ripp's Dairy Valley in Dane, foreground

On a recent cool, summer evening in the rolling hills just outside Madison, the capital of America’s Dairyland, the lofty pole barn of Ripp’s Dairy Valley farm briefly transformed into a town hall meeting.

As twilight descended, a crowd of more than 60 farmers, public officials, dairy workers and rural residents grabbed bowls of ice cream and took their seats for the event, sponsored by the Professional Dairy Producers of Wisconsin, to learn about farming and discuss the direction of the state’s signature industry.

Chuck, Troy and Gary Ripp, owners of the farm, a large operation with about 850 milk cows, faced the crowd and fielded questions. The main topic of the night, elevated to the forefront by the election of President Donald Trump: immigration.

“Well, it’s a hot topic, and every night on the news you hear about building a wall and what we’re gonna do, like we’re gonna kick everybody out,” Chuck Ripp told the group. “First of all, Trump has a lot of power, but I don’t think he has that much power. He doesn’t quite understand, I don’t think, everything that involves in our lives all the time here on the dairy farm.”

Immigration as a top line issue for dairy farmers would have been unthinkable just a generation ago when Wisconsin’s agricultural landscape was dominated by small and medium-sized dairy farms run by the families that owned them.

Now, the nation’s No. 2 milk producing state is home to a growing number of large concentrated animal feeding operations. These businesses, which operate 24/7, year-round, require work that farmers insist most Americans will not do.

Nationally, more than half of dairy workers are immigrants, according to a 2015 industry-sponsored study, with farms that employ immigrant labor producing 79 percent of the nation’s milk.

The Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism asked farmers, academics, a union activist and the state’s recently retired agriculture secretary how Wisconsin’s dairy industry came to rely on immigrants to keep it afloat — and what could be done to put it on a more sustainable and legal path.

The answers include raising wages and benefits paid to dairy employees, increasing automation so jobs are less physically demanding and farmers need fewer workers, and changing federal law so immigrants can work here legally.

How did we get here?

Shelly Mayer believes the problem is broader than the dairy industry.

“We’re just short of people,” said Mayer, executive director for the Wisconsin dairy producers’ group that helped organize the get-together at the Ripp dairy farm.

“Immigration is … really a symptom of a rural labor shortage,” she said. “I don’t think any of the farmers are trying to work around the system. They just need a person they can rely on to care for cows.”

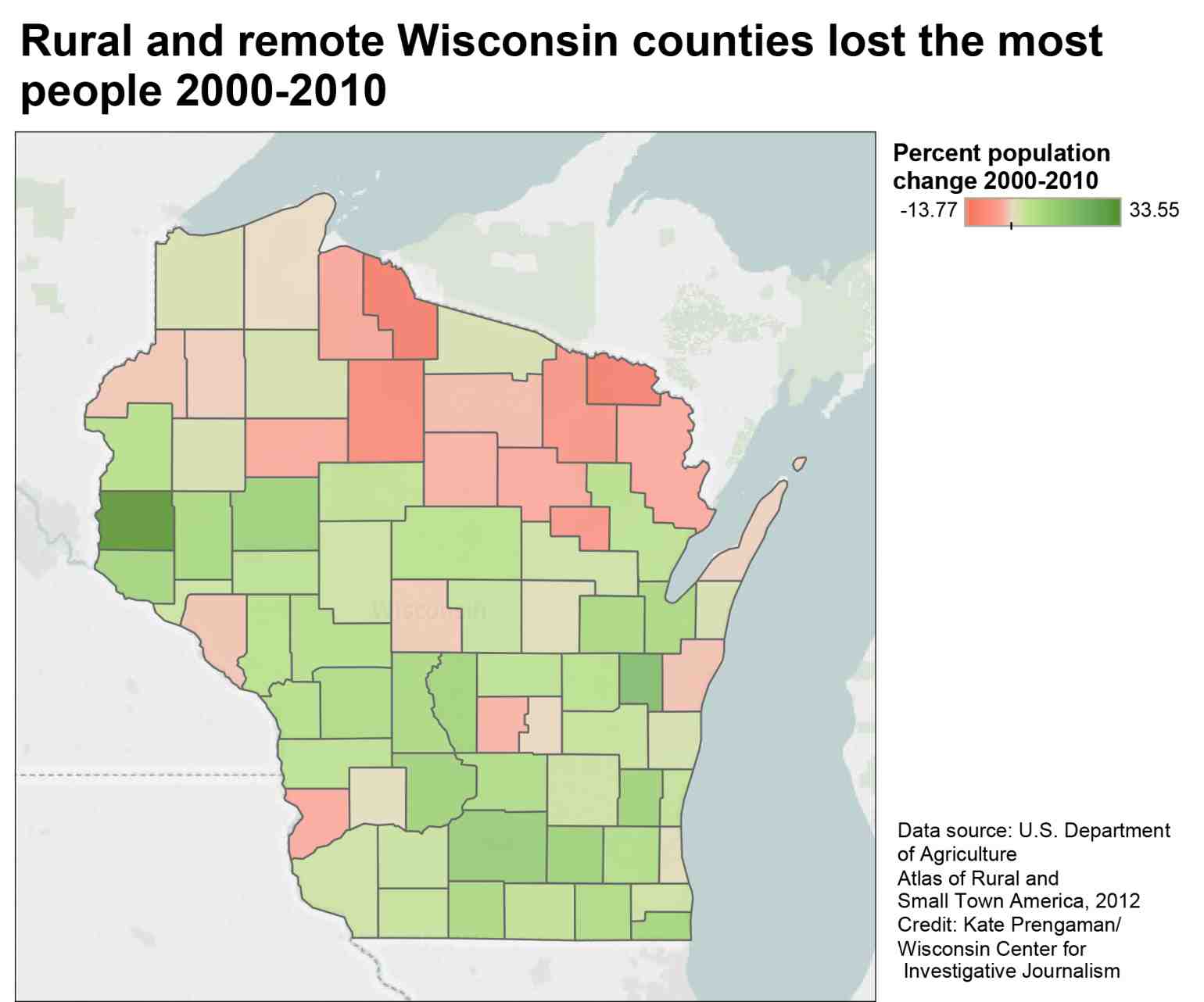

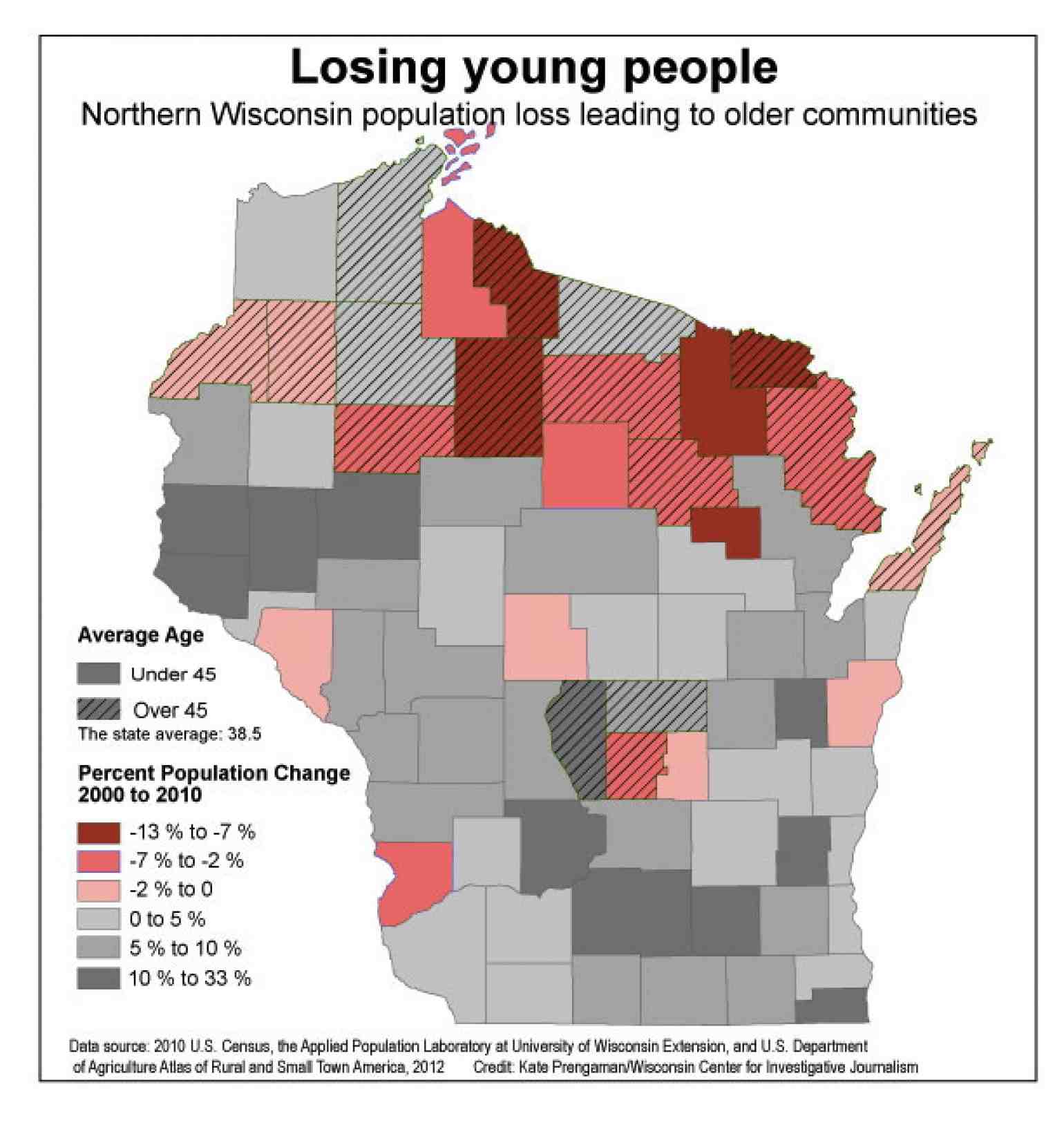

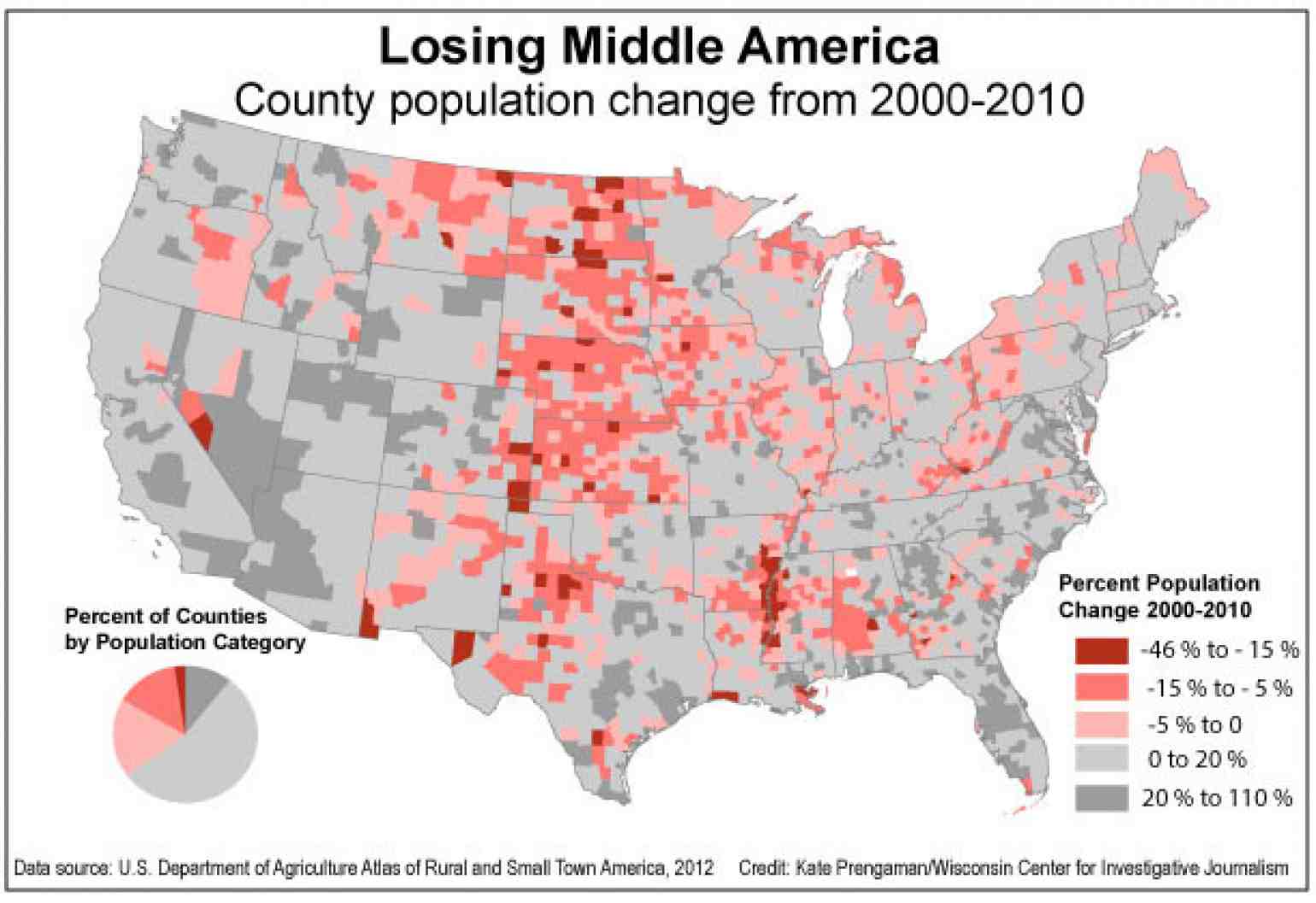

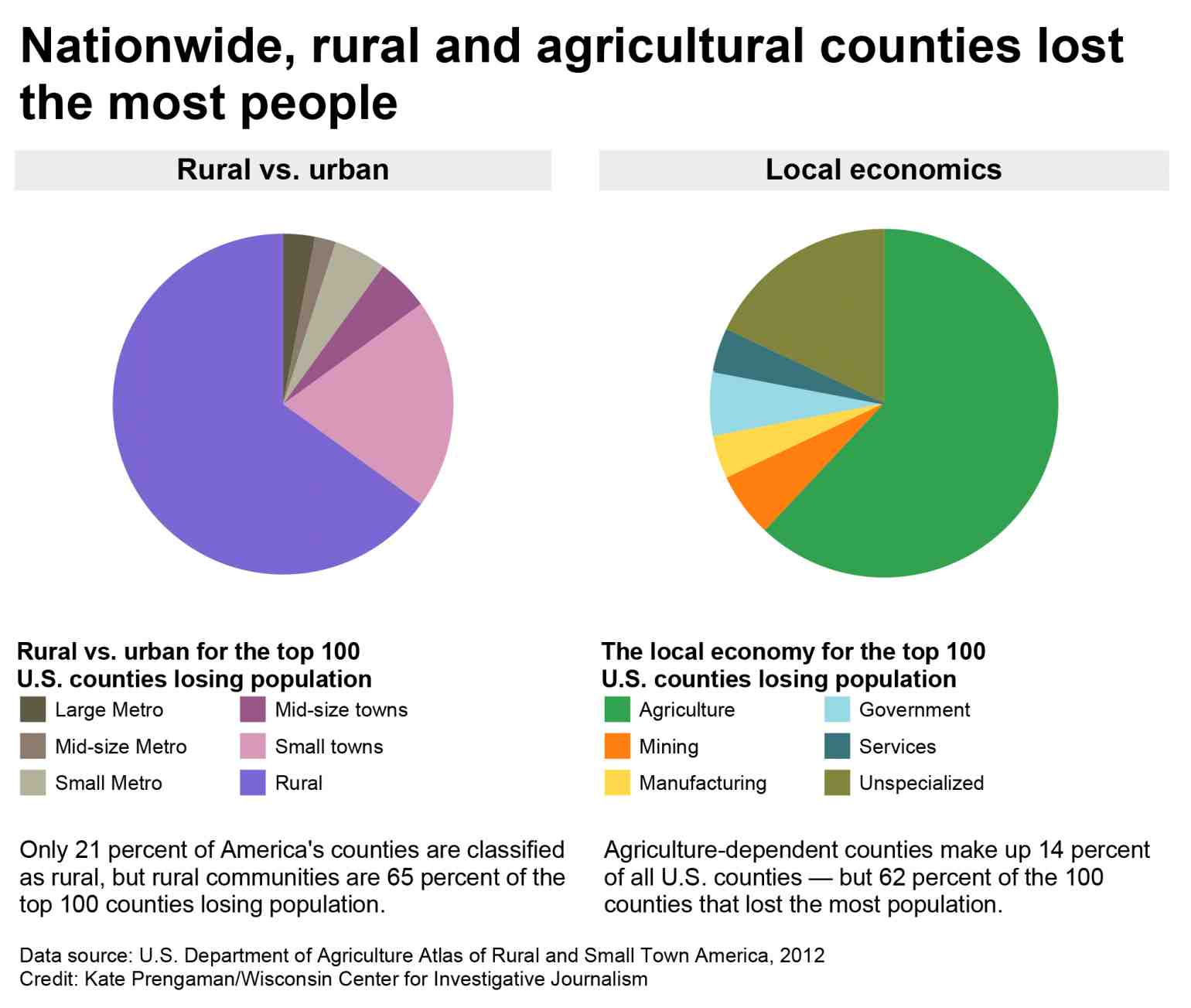

There is no doubt that in recent years, residents have fled rural counties in Wisconsin, and many of them are young people. Between 2000 and 2010, Wisconsin’s population grew by 6 percent, but more than a quarter of Wisconsin’s 72 counties lost population. Most of the losses in Wisconsin and nationally were in rural areas where the main industry is agriculture, the Center has reported.

These days, Wisconsin businesses complain they cannot find enough workers to fill positions as the state’s near-record 3.2 percent unemployment rate means just about everyone who wants a job has one.

At the same time, federal figures show the number of hired workers on dairies in Wisconsin has nearly doubled since 2006 to about 14,000 — a reflection, Mayer said, of the move away from family labor that fueled small farms that once dominated the industry.

Ben Brancel, Wisconsin’s recently retired agriculture secretary, said the nation’s “cheap food” policy puts pressure on farmers to keep down costs, including labor. Immigrants, he said, “provide valuable support for our food-producing systems.”

‘Rather have a Latino’

Another factor is what farmers such as Tim Keller describe as a lack of work ethic by U.S.-born workers. Keller milks 330 cows on his 600-acre farm near Mount Horeb, about 25 miles west of Madison. He has five immigrant workers, including his “right hand man” who hails from Uruguay. Keller said the employee, who is here legally, has worked for him for 11 years.

Keller said he voted for Trump but disagrees with the administration’s threats to deport all undocumented immigrants. His Hispanic employees are hard-working — and highly valued, Keller said.

“Even if an American guy came up right now, I don’t know if I’d hire him,” Keller said. “I’d rather have a Latino.”

Chuck Ripp said before his farm started to grow, he and his brothers hired local high school students to help on the farm. But they never lasted. Now, 11 of the 12 non-family members who work there are Hispanic immigrants.

“We cannot find the American person to come in and work full-time on a dairy,” Ripp said in an interview. “It’s too many long hours. It’s too hard of work. And it’s seven days a week, 365 on a dairy farm. … A cow does not take a day off.”

He added, “We’ve run ads in the papers, looking for milking technicians or people to help milk cows and things like that. We don’t even get a bite. We don’t even get calls.”

In recent years, dairy farmers have become accustomed to cheap, flexible labor, said Jill Lindsey Harrison, a former University of Wisconsin-Madison faculty member who studied the rise in immigrant dairy workers in Wisconsin, a trend that started around 2000.

Harrison, who now teaches at the University of Colorado-Boulder, said such workers are willing to work long hours under “pretty crummy” conditions to support themselves and their families.

Wisconsin farmers have said it is nearly impossible to convince Americans to take the jobs, which entail cleaning out stalls, night, weekend and holiday shifts and working in every type of weather, including subzero temperatures, blazing heat, rain and snow.

Immigrant workers who do not have legal status, Harrison said, are easier to manage because “they’re going to not ruffle any feathers.” They are generally “afraid to speak up for themselves and demand better jobs,” she said.

Activist: Boost pay, benefits

Neil Rainford is a long-time labor activist who has negotiated wages for employees in workplaces including a municipal sewer plant, jail and aluminum manufacturing, which he said are “easily as dirty, dangerous and hard as dairy work.”

“In all those communities, it was a matter of what wages needed to be paid to get people to do onerous jobs that most people don’t want to do,” said Rainford, a Madison-area field representative for AFSCME who was speaking for himself and not the public employee union.

Rainford does not buy the argument that Americans will not clean out barns or get up in predawn hours to milk cows.

“The labor market for the dairy industry in Wisconsin is the same as any other labor market,” he added. “If demand outstrips supply, then the price — of labor in this case — must increase to meet demand.”

Rainford said relying on immigrant labor drives down wages to “unnaturally low” levels for dairy work, meaning U.S. citizens cannot get jobs with family-supporting income in their home communities.

It is not good for immigrants either, Rainford argued, noting that undocumented workers do not qualify for public benefits other workers do, such as Obamacare or government-subsidized health care.

Such workers, he said, are allowed “to labor without the basic social protections that are part of our social and legal compact are easily exploited, suffer sub-market wages and benefits and are denied many of the basic minimums that we have agreed upon as a society.”

But raising wages could leave farmers short when the sometimes-volatile price of milk drops, Oconto Falls farmer Tim O’Harrow said at a forum on the future of the immigrant dairy workforce in Madison last month.

“If we pay [workers] more, how do I get the money out of you [consumers]?” O’Harrow asked attendees at the Cap Times Idea Fest. “Milk is a commodity. We don’t control the price.”

Brad Barham, a professor of agricultural economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told the group that immigrant labor “keeps the economy of rural Wisconsin humming” and “it is not replaceable by domestic labor — it’s not going to happen.”

Shortage prompts higher wages

Farmers insist their immigrant workers are paid fairly, and that pay is rising.

In just the past year and a half, Ripp said his farm boosted starting wages from $8.50 an hour to $11 — plus housing — as the flow of immigrants crossing the southern U.S. border has slowed. Workers with their own housing start at $12 an hour, he said. Some of his longer tenured Hispanic workers earn $15 an hour.

Dane County, where the Ripp farm is located, considers $12.50 an hour and above to be a living wage.

America’s No. 1 milk producer, California, is raising the minimum wage for nearly all workers, including those in agriculture. By 2023, farmers and other employers will have to pay at least $15 an hour. Employees working more than eight hours a day or 40 hours a week also will be eligible for overtime pay.

But Chuck Ripp said in an interview that raising pay too much could hurt the dairy industry, which has been hit by low milk prices.

“As labor costs go up, people go out of business, plain and simple,” he said. “If it gets too high, people are going to say, ‘I just can’t do this anymore.’ We’re going to lose some farms. And I don’t think that’s what the economy wants.”

“We could probably get them [U.S. workers] to come with a lot higher wages,” Ripp said. “But the turnover would be very high.” Troy Ripp added that it would probably take three to four domestic workers to cover the shifts that one of his immigrant laborers is willing to work.

Machines vs. immigrants

Philip Martin, an expert in agricultural employment, said farms can deal with labor shortages with the help of Congress, increased automation and better pay and benefits. Martin is a professor emeritus of agricultural and resource economics at the University of California-Davis.

Martin said farm owners need to increase mechanization — such as automatic cow feeders and robotic milking systems — to improve productivity, make jobs less physically demanding and ultimately shrink the size of the workforce. He noted that such labor-saving devices have led to a sharp decline in the proportion of the U.S. workforce engaged in agriculture. About 200 years ago, 72 percent of employees worked on farms. Today, it is less than 2 percent

Mark Misch sees the trend toward mechanization as he travels the Upper Midwest selling cow waterbeds, which are considered more comfortable for the animals.

“A lot of people are looking into robots to replace the labor, having a robot do it,” said Misch, who works for DCC Waterbeds in Sun Prairie. “It could be a robot that milks the cows. It could be a robot that feeds the cows. There’s robots that push the feed up to the cows, so the people don’t have to do those jobs.”

Former ag secretary: Change the law

Martin said more machines and better pay will not be enough, however. He noted that Congress is considering expanding the guest worker program to include dairy workers.

Currently, the so-called H-2A program is confined to seasonal farm workers. U.S. Rep. Dan Newhouse, R-Washington, has proposed allowing dairy farms to bring in guest workers, calling it “a small starting point of relief” for farmers needing workers. The measure passed the House Appropriations Committee in July but still needs full House and Senate approval.

Brancel agrees immigration law needs to be changed. Brancel, who served as a Republican lawmaker and state-level director for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, said politicians in Washington, D.C., need to stop arguing immigration policy “at the extremes” and adopt law changes that recognize the need for immigrant labor in agriculture while still limiting the people who can qualify for citizenship.

“Unfortunately right now, there isn’t any stability in immigration policy,” said Brancel, who retired from public service in August to run his beef cattle farm in central Wisconsin.

Chuck Ripp also wants changes. He worries about his workers being arrested because some cannot legally drive in Wisconsin. And some of his employees, like Sergio Rivera — who has worked on the Ripp farm for 14 years — can go long periods without seeing their extended families because they fear being barred re-entry into the United States.

“I like [to go] back to Mexico to see my family … but right now it’s just more hard,” said Rivera, who cares for calves on the farm.

Being denied re-entry would mean Rivera would be separated from his wife and daughter, who live with him on the farm. That bothers Ripp.

“I really like these guys, I get to know them well, they’re working hard for me,” Ripp said. “It would be nice for me to know that Sergio could go home and then in a month come back, but right now, we’re all afraid that once they leave, once they go into Mexico, can they get back into America?”

There is anecdotal evidence that some immigrant workers are leaving Wisconsin in the face of stepped up enforcement.

In the Chicago regional office of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which encompasses six states including Wisconsin, arrests are up under Trump, from an average of 538 per month at the end of President Barack Obama’s presidency to an average of 776 arrests per month for the first six months under Trump.

At the same time, deportation rates have gone down, in part because of record-level backlogs in the courts. In the Chicago region, the pending case backlog is about 25,700, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University.

Despite the threat of arrest emanating from Washington, Harrison said she does not expect a wave of voluntary departures.

“You’ve got people who are desperate to be here to work,” Harrison said. “So they’ll keep a low profile. They’ll say ‘yes’ to what’s offered to them. They’ll make as much money as they can while they can. It’s heart-breaking.”

Elise Foley of HuffPost contributed to this story, reported in collaboration with HuffPost as part of its Listen to America bus tour. The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us