Where Coliforms Were Found In Wisconsin Utility Water In 2015

As the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources noted in its 2015 annual report about municipal water utilities, coliform bacteria are found in systems across the state. In fact, water samples testing positive for these bacteria outnumbered those showing higher-than-permitted levels of other contaminants.

August 4, 2016

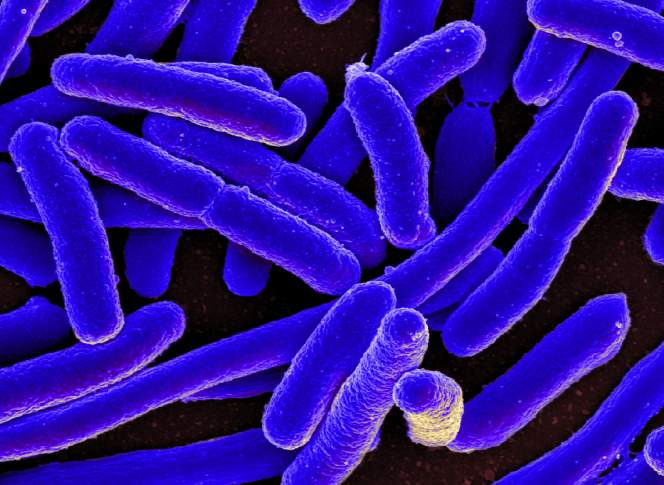

Colorized Escherichia coli bacteria via electron micrograph

As the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources noted in its 2015 annual report about municipal water utilities, coliform bacteria are found in systems across the state. In fact, water samples testing positive for these bacteria outnumbered those showing higher-than-permitted levels of other contaminants. The DNR’s report does not indicate where these bacterial detections were found in the state.

However, information about where coliform bacteria were found in public water utilities is available. Using records from a DNR online database, the following map and chart show the counties and utilities where this contaminant was detected.

The state can’t test for every type of bacteria, viruses or protozoa that might be present in drinking water, so regulators often use coliforms as “indicator organisms.” Coliform bacteria are just one subcategory of the many microbes that can contaminate drinking water. In fact, many coliforms aren’t necessarily dangerous, though others are, including E. coli. But these bacteria are common in the digestive tracts of many mammals, so when they show up in drinking water, that suggests there’s human or animal fecal matter contamination, which means other, potentially more troublesome microbes may also be present. If coliforms are detected, state regulators and local water officials can run further tests for specific kinds of bacteria and viruses.

The federal Safe Drinking Water Act requires all public utilities to monitor for coliform bacteria, under specifics the United States Environmental Protection Agency spells out in its Total Coliform Rule. Bigger utilities are required test water samples more frequently, and that any that finds coliform bacteria must conduct follow-up testing. This practice helps to explain why some utilities, like the city of Eau Claire’s, showed high numbers of positive samples in 2015. (A major leak from Eau Claire’s sewer system into the Chippewa River was recently detected, though it’s not clear how long it lasted or how it may have affected the quality of nearby groundwater used by the city’s water utility.)

It’s important to understand that about one-quarter of Wisconsinites get their drinking water from private wells, and information about the quality of these sources is not included in this data set. It’s possible to live in an area where public water utilities don’t have a known coliform problem but private wells do — in fact, that’s exactly what’s happening in Kewaunee County and elsewhere around the state. For more information about this aspect of drinking water quality, the Center for Watershed Science and Education’s Wisconsin Well Water Quality Viewerprovides local data about quality issues in private wells across the state.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us