When The University Of Wisconsin Persecuted Gay Students

For nearly two decades after World War II, leaders at the University of Wisconsin-Madison systematically outed gay students to their families, extended harsh punishments for suspected homosexual activity and participated in harmful attempts at psychiatric treatment.

June 18, 2019

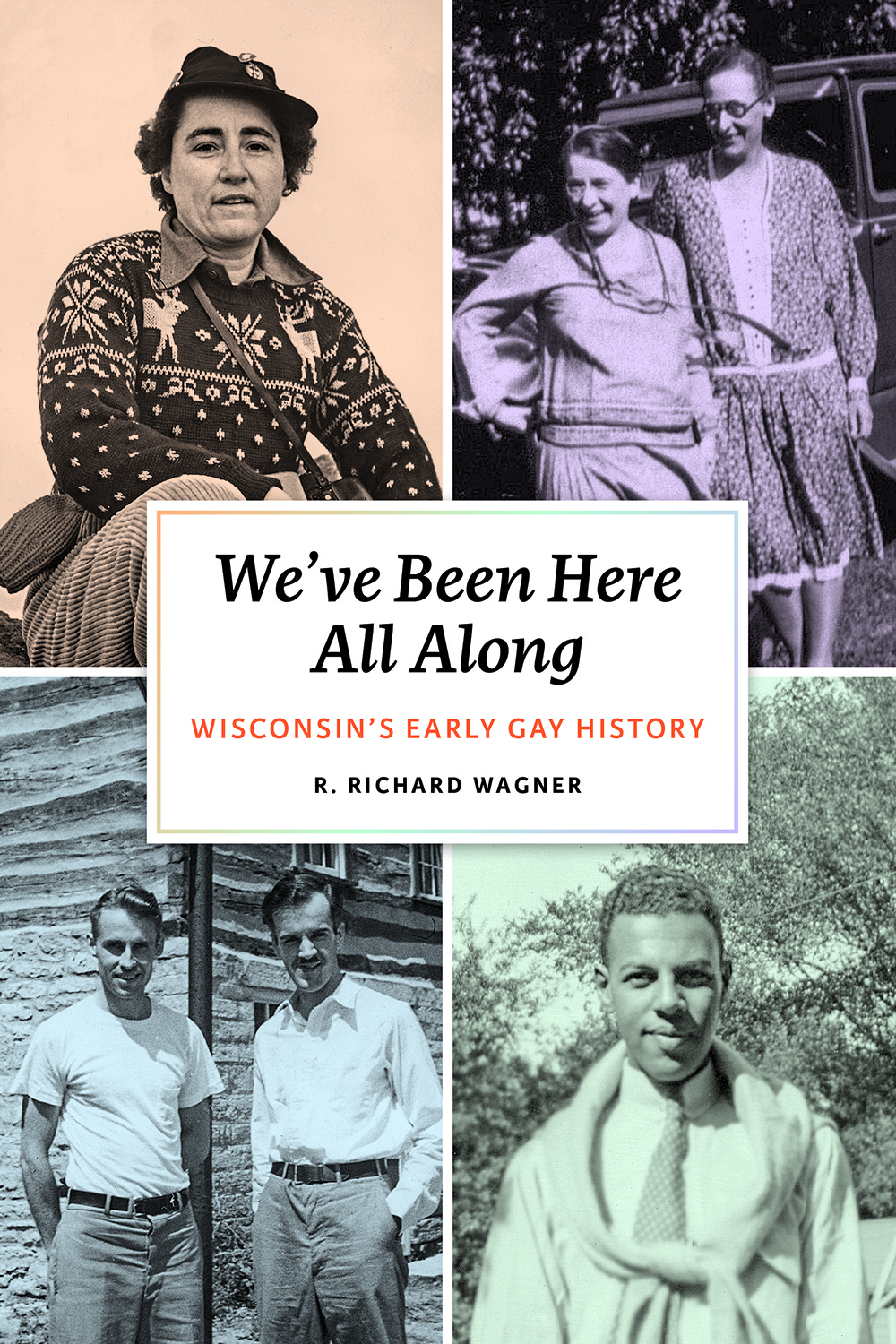

UW Bascom Hall 1950s postcard crop

Wisconsin’s LGBTQ residents are more visible than ever in the state. Despite facing ongoing prejudice, Wisconsin’s queer community enjoys rights that were not extended to previous generations, including protections against workplace discrimination and the equal right to marriage. On a political level, gay and lesbian officeholders represent Wisconsinites in local, state and federal elected positions. But inclusion of LGBTQ Wisconsinites into the state’s cultural, educational and political institutions is a relatively new development. For much of Wisconsin’s history, the contributions of queer men and women went largely unrecognized in the public sphere; instead, law enforcement, institutional leaders and the media most often acknowledged their presence by way of public derision and persecution. Through meticulous archival research, R. Richard Wagner — the first openly gay Dane County supervisor — explores the lives of pre-Stonewall queer Wisconsinites in the 2019 book We’ve Been Here All Along: Wisconsin’s Early Gay History published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press. From local newspaper coverage of the trials of the gay Irish poet and playwright Oscar Wilde to public depictions of queer social life in the 1960s, the book sources news clippings, personal letters, photography and official records to shine a light on early LGBTQ experiences in Wisconsin. An excerpt from the book recounts a post-World War II period during which leaders at the University of Wisconsin-Madison systematically persecuted students who were suspected of being gay. During this time, university officials ruined the academic and future careers of many students. They did so by outing the students to their families, extending harsh punishments for suspected homosexual activity, including expulsion, and participating in harmful attempts at psychiatric treatment, including what is today known as conversion therapy, a debunked practice that seeks to alter the identity of its subjects.

“K—— tells me that his parents know nothing of the statement which he made to the police, nor anything whatsoever concerning the incident,” a school official wrote in 1948. “I felt that it might be well to inform them of the facts.”

In fact, in this period, the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s policy required officials to tell parents about their sons’ homosexual behavior, effectively outing them without consent. One student asked “that the disgrace and shock to his mother” be taken into consideration.

The official response noted in his file was that “It was agreed that C——’s parents should be notified.” One student pleaded for mercy, writing, “The degree means so much to me and to my parents.” Another student discipline record shows that a doctor met with both a student and his father, though at separate times.

In one case the university did not need to inform the parents because the matter was covered in the newspaper. But some parents did correspond with Dean Theodore Zillman. One student’s parents wrote, “It is our aim to place him under the care of a competent psychiatrist and also to arrange for a complete physical check-up at the Mayo Clinic. Our one purpose in life will be to get him back on the right path so he can take his proper place in society.”

The dean responded, “I feel certain that the understanding and assistance which D——’s situation is receiving from his parents can only lead to a happier life for him.” This student was eventually let back into the university.

For some, getting caught resulted in coming out, not only to their parents but also to clergy.

One student, a member of the First Unitarian Society of Madison who worked with the church’s youth group, felt the “situation necessitated” that he apprise the Reverend Max Gaebler. After the student offered to resign from the church’s high school youth group, Reverend Gaebler was “so impressed with his complete frankness, his intelligent recognition of his difficulty and his eagerness to seek further psychiatric assistance” that Gaebler refused the resignation and wrote to Dean Zillman on the young man’s behalf.

The assistant director of the Wisconsin Union provided another character reference, and the student was permitted to continue at the university, though he was placed on disciplinary probation. In another case, a young man’s attorney quietly withdrew from the record a pastor’s letter written as a character reference — perhaps the clergyman got cold feet.

One case put the university’s policy to a real test.

An official wrote, “I feel that this student would benefit by administrative handling and would recommend that his father, a physician, should be informed and cooperate in any therapeutic plan.” However, the student expressed “the hope repeatedly that his parents learn nothing of the affair.”

Ultimately, the father was informed and called the dean to arrange a meeting for Wednesday of the following week. But on Monday, the family’s pastor called to report the father had suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and passed away.

The student told the school officials his father had died “with little or no insurance and while his mother insisted that he finish out the semester, he doubted that he could return to Wisconsin in the fall.” The school official handling the matter concluded, “I do not think that there should be anything further done at this time.”

Before “coming out” and “outing” were part of the gay dialogue, the university already had a decided policy. Getting caught as a homosexual could mean a notation on a student’s official transcript that the individual was “not entitled to honorable dismissal.” This was similar to the military’s dishonorable discharge.

When former Wisconsin students sought to apply to other institutions, their homosexual pasts followed them, thanks to university officials. Regularly, UW staff sent out letters to officials at other universities, stating, for example, “Mr. D—— was unfortunately involved with a group of our students last spring who confessed to homosexual behavior,” or that a student’s “problem related to a sexual aberration.”

Some letters not only mentioned the incidents but also contained notes from students’ medical records, such as, “He is a passive individual. He recognizes that he is easily disturbed and led by other more aggressive and dominant personalities.”

When a student withdrawing from Wisconsin asked if another college would hear about his case, the response was clear. One doctor wrote, “I pointed out to him that it was standard operating procedure for one university to inform another, in the case of a transfer student, not only of his academic work but of anything which might bear on his total personality picture.”

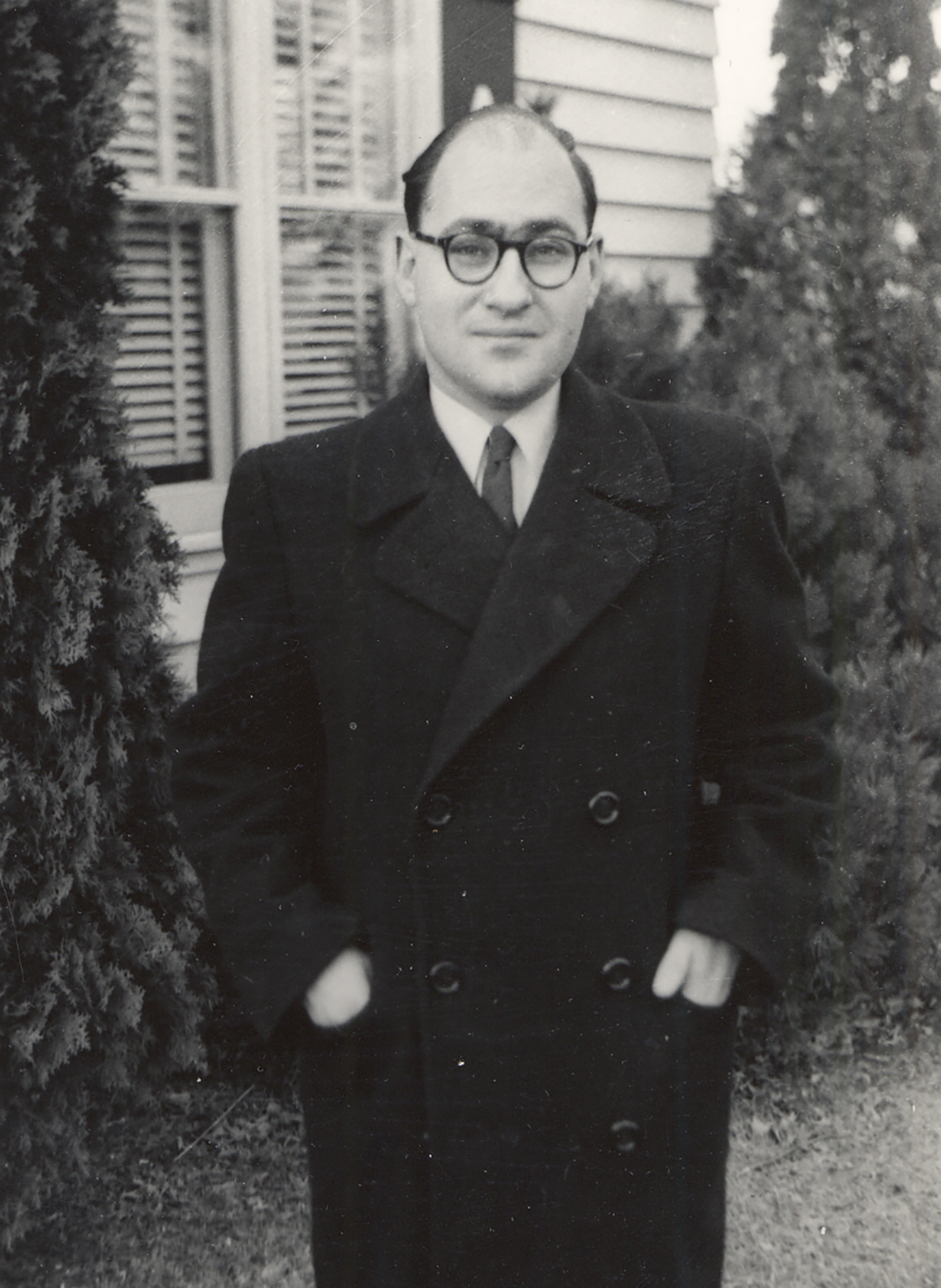

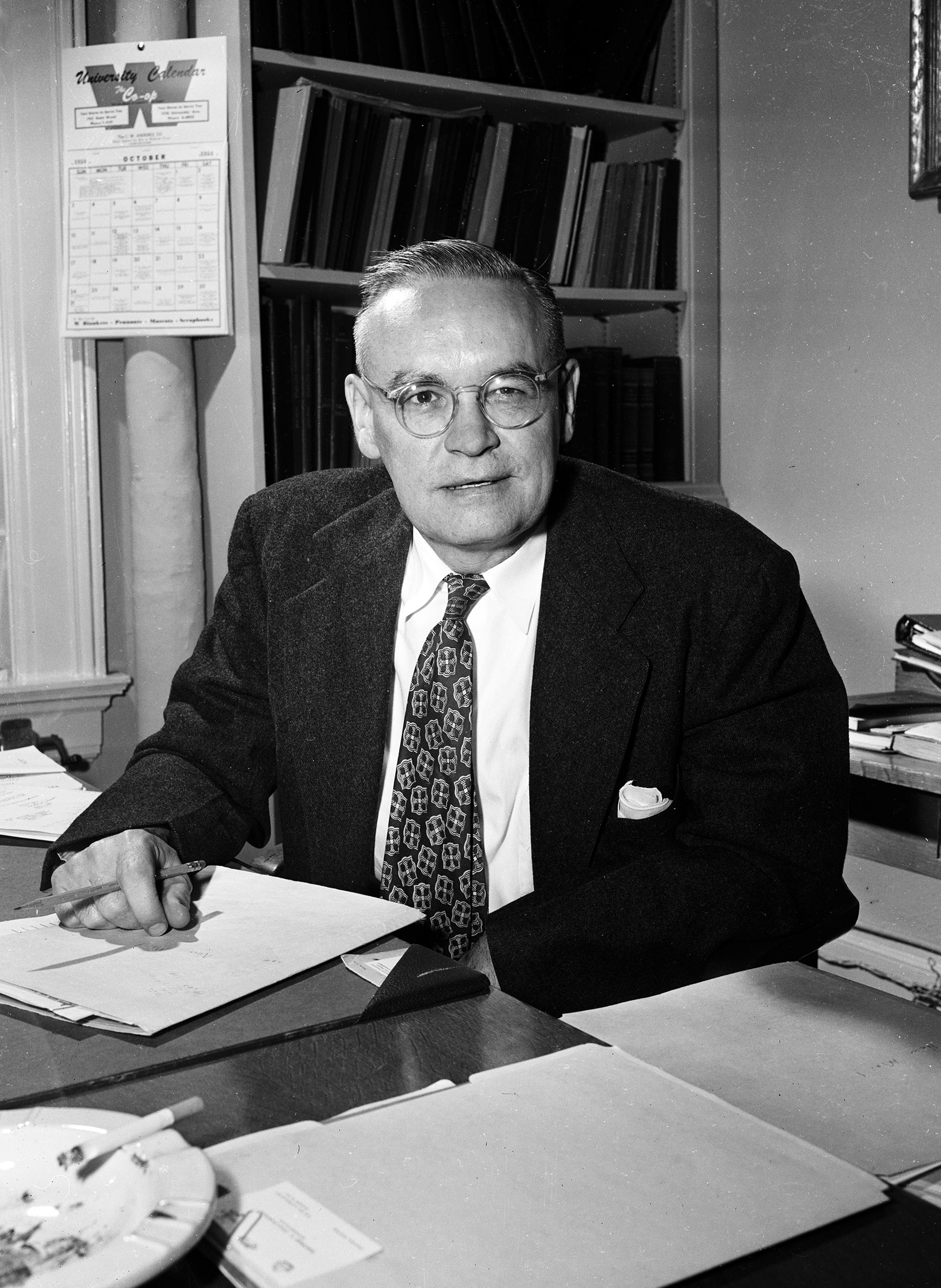

The man who sent most of these letters was Dean Zillman. Originally from Chicago, he had received his bachelor’s degree in 1926 from Wisconsin, where “his special fields of study were administration, psychology and psychiatry.” He attended law school and practiced law in Chicago, served in the army as a major, and became director of the UW Office of Veterans Affairs after the war.

In May 1950, he became the university’s dean of men, in charge of male student discipline. At this time, the university had a policy of acting in loco parentis to control student behavior in nonacademic matters. In a 1954 interview about students, Zillman explained: “I try to help them think through their behavior . . . to help them profit from their mistakes.” However, he did have a reputation as a disciplinarian. In the same interview, he stated, “They must realize they have to follow laws not individual dictates.”

Students understood that university officials making others aware of their homosexual status could be harmful.

One former student pleaded, “My position is particularly trying since without what is termed an ‘honorable dismissal’ from the University, no college however small will accept my application.”

One black student set to graduate was to have his degree withheld, but a mix-up sent it to him anyway. He wrote to Dean Zillman in Madison while doing summer work in Tuskegee: “I believe that I can be of great service to my people if I am allowed to remain here. There is a great need among Southern Negroes for good teachers.”

Dean Zillman then corresponded with a psychiatrist in Tuskegee who was treating the young man: “We feel that the homosexual activity which he did exhibit on one occasion here demanded of us that any future employer of his be alerted to his difficulty.”

Zillman was concerned that the Tuskegee officials did not know about the young man’s homosexuality and was hinting that the psychiatrist should tell them.

“Have we played fair with Tuskegee Institute under these circumstances?” Zillman asked. The doctor did not want to reveal patient information, but the matter became moot as the student left Tuskegee after the summer.

Wisconsin officials also cooperated with the military concerning former students.

In one case, the military had the police record from a student’s campus days and also knew the individual had visited the university psychiatrist. In this case, the navy commander of a Board of Officers wrote, “It is recognized that frequently psychiatric reports on a patient are unavailable but due to the importance of this matter, both to Mr. K—— and to the U.S. Navy, it is requested that either the report or a paraphrase of the report be made available to this Board.” The university could not do so in this case because the doctor involved had left the university, taking his patient records with him.

Psychiatrists treating students for homosexual problems often believed the students would “benefit rather well and rapidly from psychiatric help.”

“He is amenable to psychiatric treatment,” wrote one. Another described a student who “proved to be a very cooperative patient and anxious to help himself and improve his situation.”

George Chauncey has noted that some American psychiatrists from this era believed society should not treat as sexual psychopaths the “relatively harmless nonconformist, such as people who engaged in premarital sex or homosexual relations, so long as they kept their behavior hidden.”

Not all cases could be dealt with so easily or quickly, however. Some students continued to be seen for incidents over a long period; one case covered “a considerable period of time during which period they have been in contact with Dr. [Annette] Washburne’s office.”

And not all students were thought of as suitable for a cure.

One university psychiatrist wrote of a student he treated, “You may recall that we were by no means hopeful of what could be accomplished in the way of therapy. Our attitude was largely due to the belief that we were dealing with an essentially inadequate personality. . . . It is believed that this student will not substantially benefit by psychiatric therapy due to a lack of desire to effect a substantial change in his personality structure.”

Another psychiatrist admitted “psychotherapy under compulsion is difficult.”

Even when a case was referred to a psychiatrist, the therapy was not always successful. A student caught “in flagrante delicto” in the UW Arboretum in the fall of 1953 had been seen “for the past two years and was making excellent progress with his problem” according to the record. Excess use of alcohol was blamed for his relapse in 1953.

The Student Health Service put great store in applying “extensive objective psychological tests” to these students. The list of tests described as “psychometric” included the Bernreuter Personality Inventory, P-S Experience, Problem Checklist, Minnesota-Multiphasic, Wechsler-Bellevue, and Rorschach.

One report on a student opined that the individual was “devoid of insight and exhibited marked emotional instability and immaturity during each conference, which apparently was associated with his former experimental incident of homosexuality in 1948.”

The Student Conduct Committee’s view on disciplined students who might be permitted to continue or, if they had been suspended, seek readmission was expressed in the statement: “You were to receive psychiatric treatment indicating that you had been cured of your tendencies.” Doctors did recognize that homosexual patients might experience realistic “anxiety concerning the recurrence of an investigation of events long past.”

Most students were quick to agree that they would be “happy to cooperate” in getting psychiatric treatment.

One admitted, “I made a very foolish mistake which has done irreparable harm to my character and perhaps my future. . . . To attempt an explanation is impossible; such things cannot be explained.” Another agreed he would “freely undergo any measures the psychiatrist may suggest to assure my proper adjustment in this matter.” Another stated that his “homosexual contact had been quite frequent over the period of the last two years and that it was a matter of concern to him and he sincerely wanted to rid himself of the misbehavior pattern.”

Some truly believed the university was helping them by requiring psychiatry. One police officer noted, “Mr. L—— tells me that he should see a psychiatrist but has been afraid to go.”

Many students hoping for favorable consideration by the Student Conduct Committee declared that the treatment was working. One claimed that as a result of the psychiatric assistance, he had “abstained from any homosexual activities since that date.” Another felt “certain that he has got his old difficulty well in hand and that we need have no fear on that count.” Another claimed he had “everything under control,” but the university official disagreed, writing, “I pointed out to him that this was patently not so, as evidenced by the record. He admitted the strength of that argument.”

One student made the statement that he had “not engaged in any homosexual activities at this time but that his desires to do so were sometimes extremely high.” This student felt that the doctor had “helped him some but does not believe the doctor has helped him to the extent that he can be sure of his actions.”

The Student Conduct officials firmly required a recommendation from Student Health based on a competent psychiatrist who was a member of the American Board of Psychiatrists before they would expunge a record or readmit a student to the university.

Martin Duberman provided a good example of what may have been going through the minds of some homosexual students in his classic 1991 book Cures: A Gay Man’s Odyssey, which describes his own college days at Princeton in the 1950s.

“Many of us cursed our fate,” he wrote, “longed to be straight. And some of us had actively been seeking the ‘cure.'” He says he thought “about ‘conversion’ as my only hope for a happy life” and describes “fits of remorse over quitting therapy.”

Since Duberman went on to be an openly gay public man of letters and a professor of history at CUNY, he knew these earlier impulses to find a cure were misplaced. He later observed, “Orthodox psychiatry had based its negative conclusions about homosexuality on studies of people who had come to therapists for help or on captive populations in prisons and mental hospitals.”

Duberman’s insights show the underside of therapeutic discipline as it was used on college campuses at this time, as well as the regret that could set in after cooperating in a “cure.”

On the other end of the spectrum, however, some students did not fully embrace the university policy or the therapy.

A student from Milwaukee wrote, “I don’t intend to submit myself to a court or committee to be smeared and muckraked by the local newspapers.” Yet another expressed that to acknowledge the need for psychiatry would be “incriminating.” One believed the proposed psychiatric treatment was of “a purely suggestive nature,” although he also said, “I have succeeded in accomplishing the basic requisites for a normal adjustment.”

By 1960, another man had specifically challenged the Rorschach test, explaining the “validity of which . . . is most seriously doubted by many leading men in the field.” The same student felt that since he “did not evince a hypocritical condemnation of homosexual relations as a whole while at the hearing,” this hurt his case. He further asserted, “I have never had any interest in partaking of such a way of life.”

Others rejected the judgment that they needed help altogether. “I earnestly believe I am not in need of psychiatric treatment,” said one student. Another confirmed that he had not accepted a year of psychiatric help for two reasons: “Financial limitations have been of great importance, but there has also been a sincere question in my mind concerning the real need which I have of such help.”

The consequences of engaging in homosexual activity at the university and getting caught, although not as dire as the proposed treatment of sexual psychopaths, were still severe. Some students simply packed their bags and left. One such grad student sent a telegram to his professor indicating that he would not show up for his teaching assistant sections. In one instance, five students were referred to the Student Conduct Committee and two avoided official action by “voluntary withdrawal.” One student who was dropped in 1953 took seasonal work, hoping to be readmitted. In 1956 he was granted probationary status as a student.

For students who hoped to go into teaching professions, the repercussions could be dire.

One student was informed that the School of Education had dropped him, denied him his teaching certificate, and withheld his course credits in education. Another who aspired to teach wrote, “I have been severely handicapped in seeking employment during the five year period that has elapsed since I left Madison in June 1953.”

However, in some cases, officials believed the students accepted the university’s actions. In one instance, an official noted that a student “agreed in our concern over the possibility of his engaging in the teaching profession and understood the University’s desire that he refrain from entering the teaching profession, given his present difficulties.”

No matter the field of study, many students struggled in their searches for employment due to the university’s actions.

One student wrote, “Not knowing whether the degree will be granted is making it difficult to apply for positions, and even to complete writing of the thesis.” This individual did eventually earn his degree because the psychiatrist reported that he had “made reasonable progress” and “has adjusted satisfactorily.”

Another student lamented, “Due to my not having my degree I have lost out on several job opportunities that would have been of great value.” He also eventually got his degree.

A student seeking employment with the Bank of America in California, however, learned that the university had sent a letter to the bank reporting that the young man “was involved with a group who confessed to homosexual behavior.”

And one student studying to be a doctor was told by the UW psychiatrist Benjamin Glover, “It is difficult to answer your question about entering medicine, but I believe that it would be extremely difficult for you to gain admission to a medical school under the circumstances of your past record.”

George Mosse, a gay faculty member who arrived at the university during this period, has described how he handled his homosexuality with his teaching colleagues in the history department.

In Confronting History: A Memoir, originally published in 1999, he wrote, “The closet door had to be tightly closed, and was even so with the members of this group whom I knew to have had some gay adventures when younger.”

Members of the history department may have been even more paranoid than others because a few of the students who had been caught were history majors. In Mosse’s published scholarship on masculinity, after he was more out, he wrote, “To a large extent the physician took over from the clergy as the keeper of normalcy.” As he astutely observed, “The age of personal revelations was not yet upon us.”

Women and sexual discipline on campus

Between the end of World War II and the early 1960s, while some 50 cases involving male homosexuality were being investigated by campus authorities at UW–Madison, a similar number of female students were being investigated by campus police, deans and the Student Conduct Committee, but with one interesting difference. Of the 49 cases, every woman was being investigated for a heterosexual act.

In 28 cases, the reports indicate that the women were caught in flagrante delicto or that they confessed to cohabitating or to participation in sexual relationships. A number of cases involved adultery, such as female students having sex with married men. At least half were caught in parked cars; others were spotted out in the open. One report noted that the campus police officer observed for a while to make sure he understood what he was seeing. While some officers described exposed penises and women’s clothing shed, one more delicately described “extreme intimacy.”

Finding privacy for sex on campus during these years was difficult, and women were most frequently apprehended at the Arboretum, Picnic Point, Willow Drive, and Observatory Hill.

Another twenty-one women had stayed out late or slept over at hotels with men, but women who denied that any sexual activity had occurred were disciplined for violating the sign-out regulations of the women’s residences or for underage drinking.

In some heterosexual discipline cases, the files show that campus authorities notified the woman’s parents but not the man’s.

Several couples attempted to justify their actions by pleading that they were engaged or about to be. Some couples practiced birth control by using condoms or performing mutual masturbation.

Rarely was psychiatry suggested for these heterosexually active women, and only in cases of extreme immaturity. Most of the women under investigation were put on probation, and a number were dropped from the university. The men were also disciplined.

It is fascinating that during the two decades that saw dozens of male students disciplined for homosexual activities, not a single case of lesbianism came to the attention of the campus authorities. That the total number of women under discipline for heterosexual activity nearly matched the number of men under discipline for homosexual activity shows the lopsided focus on gay men and a total ignorance or intentional avoidance of lesbianism.

This item was excerpted from We’ve Been Here All Along: Wisconsin’s Early Gay History, published by Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

Author R. Richard Wagner is a scholar and activist, and was the first openly gay member of the Dane County Board of Supervisors, where he served for fourteen years. In 1983 he was appointed by Governor Tony Earl to co-chair the Governor’s Council on Lesbian and Gay Issues, the first in the nation. In 2005 he joined the board of Fair Wisconsin to fight the constitutional amendment against marriage equality. Wagner has served on the Wisconsin Arts Board, the Wisconsin Humanities Committee, the board of Downtown Madison Inc., the Madison Plan Commission, the Madison Urban Design Commission, the Madison Landmarks Commission, Historic Madison, the Madison Trust for Historic Preservation, the board of the Olbrich Botanical Gardens and the board of the Friends of UW Libraries.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us