What Wisconsin's 2016 Voter ID Study Means And Doesn't Mean

In a study commissioned by the Dane County Clerk that was released Sept. 25, 2017, University of Wisconsin-Madison political scientist Kenneth Mayer found that the state's voter ID law did keep significant numbers of people from voting in Dane and Milwaukee counties in the November 2016 election.

October 3, 2017

Wisconsin Elections Commission polling place PSA screenshot

Wisconsin’s voter ID law, enacted in 2011, has gone through years of legal wrangling — leaving it variously in and out of effect in part or in whole — and the federal court battles aren’t over. Throughout these lawsuits, judges have also issued rulings expanding early-voting access and compelling the state government to expand efforts to educate voters on how to comply with the voter ID law.

November 2016 was the first time the state’s voter ID law was enforced in a presidential contest — an election that, in Wisconsin, also brought a hard-fought U.S. Senate race. In this election, Donald Trump would end up winning the state, the first Republican candidate to do so since 1984, incumbent Republican Senator Ron Johnson won reelection, and the GOP would capture historic majorities in the state legislature.

In a study commissioned by the Dane County Clerk that was released Sept. 25, 2017, University of Wisconsin-Madison political scientist Kenneth Mayer found that the state’s voter ID law did keep significant numbers of people from voting in Dane and Milwaukee counties in the November 2016 election. Of the registered voters in those counties who didn’t vote in the election, his research found, 11.2 percent were deterred from voting because of the voter ID law. So, while this finding shows that voter ID wasn’t the biggest factors helped keep voters in Wisconsin’s two largest counties from the polls, the voter ID law affected between 16,801 and 23,252 voters among them.

These findings have thrown fuel on the fire of an intense state and nationwide battle over voter ID laws. Their supporters, primarily Republicans, claim that these regulations protect the integrity of elections against voter impersonation fraud, despite there being no evidence that this is a widespread problem at state or federal levels. Opponents of voter ID requirements consider them to be part of a broader effort to weaken the voting power and representation of minorities, the poor, the elderly and college-age voters.

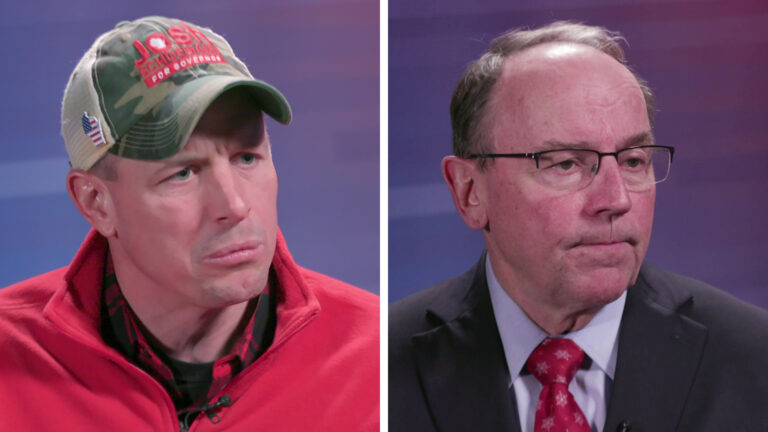

Mayer discussed the study in a Sept. 29, 2017 interview on Wisconsin Public Television’s Here & Now. Here’s what he had to say, and a few things to keep in mind about what the study means and what it doesn’t.

Voter ID laws largely deter voters through confusion.

Most of the voters whom Wisconsin’s voter ID law deterred in Dane and Milwaukee counties would have actually been legally allowed to vote.

“Most of the people who cited ID as a reason they didn’t vote actually turned out to possess a qualifying form of ID,” Mayer said on Here & Now. Some voters thought that the address on their driver’s license had to be their current address — that is not so.

For eligible voters without a valid driver’s license, it might be difficult to navigate the various other forms of identification that meet the law’s requirements, or get ahold of those forms of ID. Voter ID opponents have pointed out that minorities and the elderly disproportionately lack driver’s licenses and other forms of ID, yet Mayer’s study shows that confusion and shortcomings in state programs to educate voters about the law have potentially more impact on turnout.

The study says a lot about local disparities, not much about statewide impact.

The impact of the voter ID law fell much harder on low-income voters and African-American voters in Dane and Milwaukee counties, Mayer’s study found. Among African-American registrants in both who did not vote, voter ID was a factor for 27.5 percent, compared to 8.3 percent for whites. Additionally, non-voters making less than $25,000 per year were three times as likely as those making more than that amount to cite voter ID as a factor. In both the racial and income categories, though, each group was more likely to be deterred by confusion over the voter ID law than by actually falling short of the law’s requirements.

On Here & Now, Mayer said that the study’s findings can’t be extrapolated to the rest of the state. Milwaukee and Dane counties have the largest African-American populations in the state by a wide margin. The state as a whole has become more racially and ethnically diverse since the 1970s, but the makeup of that diversity varies widely from one locality to the next. Mayer’s study says nothing about how voter ID affected low-income voters living across the state, or, say, elderly voters in rapidly aging areas of rural Wisconsin.

The study doesn’t claim that voter ID affected the outcome of the 2016 election.

Mayer stressed that the study doesn’t indicate that Wisconsin’s voter ID law flipped any results in the 2016 election. Even had the law kept 23,252 voters from the polls — the maximum in Dane and Milwaukee counties, according to the study’s calculations — and all of them had planned to vote for Democrats, that wouldn’t have closed Trump’s margin over Hillary Clinton in the presidential race or Ron Johnson’s margin over challenger and former U.S. Senator Russ Feingold in the Senate race.

The study doesn’t attempt to gauge voter ID’s impact beyond the two counties, but that doesn’t mean it couldn’t have had broader effects on a statewide level. Confusion and impediments created by voter ID requirements, combined with wavering enthusiasm among voters and the public’s general distaste for both Trump and Clinton, might have made a huge difference as well. The study doesn’t set out to determine that possibility, though, just whether the law got in voters’ way in two counties.

The study doesn’t discuss the political motivations ascribed to voter ID laws.

Mayer’s study says a lot about how voter ID impacted Wisconsin’s two biggest strongholds of Democratic voters. Republican legislators across the country, and in Wisconsin, have been accused again and again of deliberately using voter ID laws to suppress the votes of populations that tend not to vote for GOP candidates; several of them have even made public statements to that effect.

The lack of evidence for widespread in-person voter impersonation fraud — which voter ID laws are promoted as guarding against — strengthens the case that these requirements aren’t material in protecting the integrity of the elections process. American elections are decentralized, carried out and monitored by thousands of state and local elections officials of both major political parties, as well as those affiliated with minor parties or no party at all, so organizing voter fraud on a mass level would be an extremely cumbersome enterprise.

Both Dane and Milwaukee counties have large numbers of Republican voters, but Mayer’s finding that voter ID disproportionately affected low-income and African-American voters suggest it did the most harm to Democrats, whose voting base is much more racially diverse and includes more low-income voters than Republican candidates, including Donald Trump in 2016. However, when discussing his study, Mayer was adamant about not delving into the intentions of legislators passing voter ID laws. While an observer might read between the lines about voter ID’s political impact, the study didn’t ask respondents about their party affiliations or who they voted for.

Mayer considered the empirical data from his study is enough on its own to reflect poorly on the effect of voter ID laws.

“In my view, the harm here is not simply whether the election would have changed. That’s the wrong metric,” he said on Here & Now. “When you have thousands of people who are effectively disenfranchised, unable to vote — and I should point out that about 80 percent of the people that we identified as being affected by this, the voter files show that they actually voted in 2012 — that’s a serious harm. Disenfranchising people for no reason is in itself a harm to the integrity of the electoral process.”

Other studies back up the Wisconsin study’s findings.

The findings in the UW study pertain to one extraordinary election and two counties that deviate demographically and politically from the rest of the state around them. However, this study has a lot in common with other scholarly efforts to understand the impacts of voter ID laws around the country.

A University of Houston study released in April 2017 investigates non-voters in the November 2016 election in Harris County, Texas, which includes much of metropolitan Houston. The study found that the Texas voter ID requirements did have an impact, but a small one compared to voters’ lack of enthusiasm for the presidential candidates and the candidates in a hotly contested Congressional race. About 16 percent of the non-voters surveyed for the study cited lack of ID as a reason, but only 1.5 percent cited it as the primary reason. As in Mayer’s study, most of these voters actually had the proper identification but were confused about the voter ID requirements.

Like Mayer’s study, the growing body of research about voter ID laws shows that these requirements tend to disproportionately affect racial and ethnic minorities. These studies also tend to show that the laws benefit Republican candidates, though, again, Mayer’s study didn’t look at that aspect. And, of course, all of these studies vary in their scope, methodology, and geographic and electoral context.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us