What to know about Wisconsin's inconsistent system for tracking police caught lying

What is a the legal basis of Brady lists used by prosecutors and how is this doctrine applied to identifying and tracking law enforcement officers who may have credibility issues across the state?

Wisconsin Watch

May 28, 2024

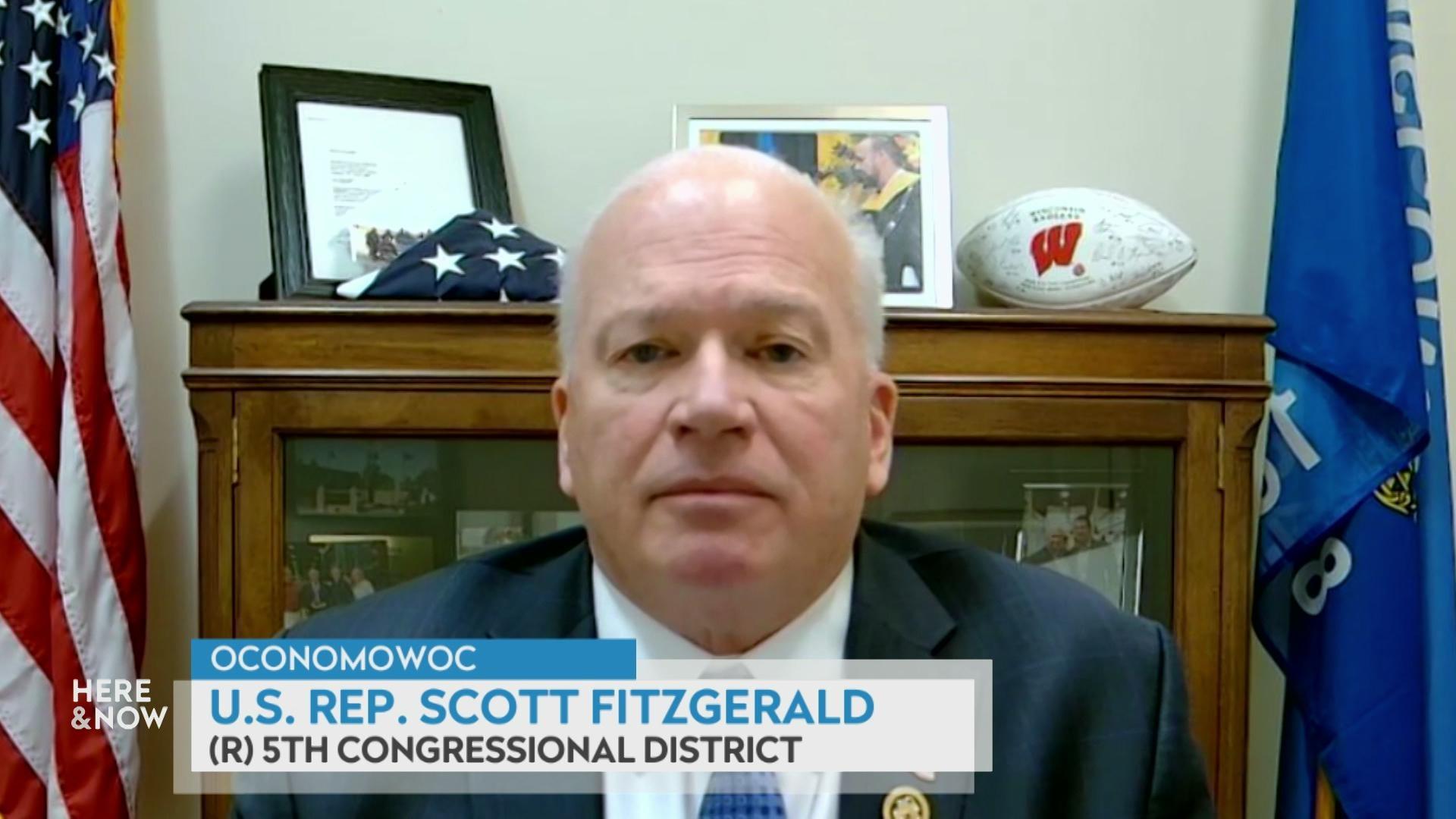

Former Appleton Police Officer Jeremy Haney, right, sits in court April 30, 2024, with his lawyer. Haney pleaded no contest to one count of misconduct in public office, a class I felony. Additional charges of forgery and obstructing an officer were dismissed. The felony conviction ensures Haney will never serve as a police officer again. Haney stated that had he received the treatment he needed for PTSD and anxiety, this never would have happened. (Credit: Shane Fitzsimmons for Wisconsin Watch)

This article was first published by Wisconsin Watch, a nonprofit, nonpartisan newsroom.

Public access to information about police officers caught lying is inconsistent across Wisconsin’s 72 counties. That’s the key takeaway after Wisconsin Watch filed records requests with every district attorney’s office and the state Department of Justice.

Here’s a recent example and a look at Wisconsin’s inconsistency compared with Colorado — the first state in the nation to mandate tracking and disclosure.

Drug investigator caught forging signatures on warrants

An Appleton police sergeant investigating suspected drug trafficking was caught forging the signatures of a prosecutor and circuit court judge on a warrant that would’ve otherwise lapsed. For this misconduct he resigned and on April 30 pleaded no contest to a single felony that carried a maximum 3 1/2 years in prison and $10,000 fine.

Special prosecutor Wendy Lemkuil said former Appleton Police Sgt. Jeremy Haney’s dishonesty has tainted other investigations by the Lake Winnebago Metropolitan Enforcement Group — a multi-agency drug task force he had been assigned as an investigator.

“It’s affected the work that other officers have done,” Lemkuil told the court. “Because now there’s challenges on a lot of different co-defendants of the initial underlying case, as well as other cases, whether or not the credibility of those cases can stand based upon the fact that Mr. Haney may have been involved.”

Even so, the Brown County prosecutor and Haney’s defense attorney agreed to a deal that spared the former officer any jail time. And the court lowered the fine to $500 plus court costs.

Sentencing Judge Raymond Huber noted that when an officer is caught being dishonest it can taint future cases they are involved in.

“I want any law enforcement officer who’s sitting out there (to know),” he said in open court, “their actions have long-term consequences.”

Former Appleton Police Officer Jeremy Haney ultimately pleaded no contest to one count of misconduct in public office, a class I felony. Additional charges of forgery and obstructing an officer were dismissed. (Credit: Shane Fitzsimmons for Wisconsin Watch)

Haney — whose plea of no contest does not admit or deny guilt — apologized for his actions.

“I’m sorry for what I’ve done,” he said. “I’m sorry to everybody involved.”

What is a Brady list?

Haney’s deliberate falsehoods — the crime of forgery — is the type of offense that can land a police officer on a Brady list. Because he’s a felon, Haney’s career in law enforcement is over.

But not all examples of misconduct are prosecuted, and officers sometimes continue to give sworn testimony against criminal defendants despite documented cases of dishonesty. Defendants often use evidence of past misdeeds to attack the credibility of their accusers. That’s why prosecutors often keep a list of officers with a Brady letter in their file, as a reminder of their constitutional duty to inform defense counsel of an officer’s past credibility issues.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1963 that police and prosecutors cannot withhold evidence that could sow doubt on a defendant’s alleged guilt. The decision, named after the U.S. Supreme Court case Brady v. Maryland, brought the term “Brady” into common use in the criminal justice system. In that case, prosecutors used the testimony of one man to help convict another of murder even though the first man had admitted to the crime. That confession was never disclosed to the defense.

The U.S. Supreme Court again expanded disclosure requirements in the 1972 case Giglio v. United States. In that case, the government had withheld the fact that it had granted leniency to a key witness in exchange for testimony used to secure an indictment.

Both cases helped establish a standard in which prosecutors must disclose any material that could be used to call into question the credibility of prosecutorial witnesses, including police officers involved in a case.

Sometimes the lists of dishonest police officers that district attorneys keep are called Brady/Giglio lists or just Brady lists. Whether a Brady violation would be admissible in court and disclosed to a jury is ultimately left up to a judge.

The consequences for flouting the Brady rule can be far-reaching. If a violation is discovered during trial, the judge can declare a mistrial and even prohibit prosecutors from using evidence called into question by the withheld information. More often Brady violations are found after a conviction and are used in appeals with the aim to overturn a conviction.

How is the Brady doctrine applied in Wisconsin?

The Brady doctrine is applied inconsistently across Wisconsin. Some district attorneys keep a list, some keep paper records on each individual case and some didn’t disclose their policies at all, saying their work files are protected from public disclosure as part of a prosecutor’s case file.

Wisconsin Watch found no evidence DOJ provides uniform guidance to local prosecutors.

Green Lake County District Attorney Gerise LaSpisa noted the state agency is “statutorily charged with providing guidance and advice to Wisconsin prosecutors.”

Several other district attorneys reported they only began canvassing local law enforcement agencies for names of potentially dishonest officers after Wisconsin Watch requested a Brady list.

“Given my recent appointment, upon receiving your initial email, I inquired from law enforcement as to whether there were any officers subject to (Brady) disclosure,” wrote Oneida County DA Jillian Pfeifer, who took office on Aug. 1.

None of the agencies reported any law enforcement officers with Brady disclosures, she added.

Oconto County DA Hannah Schuchart, who was appointed in October 2022, said she was aware of only one five-year-old case that led to that officer’s termination.

“I am developing a formal procedure for Brady lists since one did not exist prior to my appointment here,” she told Wisconsin Watch.

St. Croix County District Attorney Karl Anderson said there were no Brady list procedures when he was elected in 2021. He doesn’t send out letters but brings up the issue when he meets with the county’s police chiefs.

“I know some offices send out letters,” he told Wisconsin Watch. “I’d be curious to know how many offices do that, versus something like the approach I’ve done, or otherwise. There isn’t clear guidance on it in case law, other than we have a duty to seek it out.”

Ashland County District Attorney Blake Gross, whom Evers appointed in October, said he couldn’t locate any Brady lists left by his predecessors. But after Wisconsin Watch’s inquiry he reached out to area law enforcement for names. He learned of one corrections officer in the sheriff’s office and said he plans to regularly canvas each agency at least every year to keep his list current.

Colorado offers a statewide model

In 2019, Colorado became the first state to pass a law mandating standards for tracking dishonesty in law enforcement.

The following year a Denver Post investigation found inconsistencies in the way Brady listed officers were tracked with only nine of 22 district attorneys willing to release their lists.

A follow-up bill expanded disclosure requirements to make Brady list policies and mechanisms transparent to the public. But how it worked out in practice is debatable.

Unlike Wisconsin, Colorado maintains a searchable Peace Officers Standards and Training (POST) database that includes decertifications and disciplinary files including untruthfulness. The 2021 law required dishonesty flags be made public.

Jeffrey Roberts, executive director of the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition, points to recent watchdog reporting that found gaps in the data and inconsistencies in enforcement.

“What is unclear to me is how complete this is,” Roberts said of the state-run database.

The listings of dishonesty flags don’t go further back than 2022, when state lawmakers mandated the data be publicly available.

“It’s a lot better than it was, as far as disclosure, but there’s still issues with it,” he said.

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us