What more at-home COVID-19 tests mean for Wisconsin's pandemic surveillance

A new coronavirus subvariant is spreading, a combination of vaccination and past infections have provided some level of broad immunity, and public health officials are keeping tabs on multiple data sources — case counts, hospitalizations and wastewater — to gauge the threat of emerging outbreaks.

By Will Cushman

April 7, 2022

Light shines in to an empty ICU room on Jan. 5, 2022, at Meriter Hospital in Madison. (Credit: Angela Major / Wisconsin Public Radio)

As at-home antigen testing for the coronavirus becomes more accessible, are daily COVID-19 case counts becoming less reliable? Does this change in testing practices possibly obscure trends in the virus’s transmission? How else might health officials keep tabs on the disease to ensure that hospitals and public health departments are prepared for future outbreaks?

These questions are at the forefront as the United States enters a stage of the pandemic in which yet another extremely contagious subvariant, omicron BA.2, is spreading amid minimal public health restrictions and shifting resources for responding to COVID-19.

Average daily case counts have long provided a snapshot of the disease’s movement through communities. Testing providers are required to report positive COVID-19 results to public health authorities. In Wisconsin, these reports ultimately make their way to the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, which in turn calculates daily statewide case counts that it updates five days a week.

But with rapid at-home tests becoming much more widely available since late 2021, an unknown but potentially large number of positive test results are going unreported. While this dynamic may pose a challenge to public health officials tracking COVID-19, the challenge is not insurmountable. That’s according to Ajay Sethi, an epidemiologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“The fact that we have home-based testing is a good thing,” Sethi said. “While it may compromise our ability to have a good record of cases that are in the community, we don’t necessarily want to abandon this very important way that people can test and take action, so we have to find a workaround.”

In fact, multiple workarounds are taking shape to ensure that COVID-19 surveillance remains adequate despite a future with fewer reported test results. These include sampling community wastewater for genetic material from the SARS-CoV-2 virus and keeping tabs on the number of people seeking health care for covid-like illness, similar to a long used strategy for tracking the ebb and flow of seasonal influenza.

Another more limited workaround depends on systematically testing the same group of people in a community on a regular basis — a strategy known as sentinel surveillance that can provide a snapshot of transmission occurring in the wider community.

Even with more people getting positive test results via at-home testing, Sethi said average daily case counts remain a useful, if imperfect, metric for forecasting new and worsening outbreaks.

“I do not ignore the case data simply because it’s not representative, mainly because it’s never been representative of everybody who should be getting tested,” Sethi said. He added that the shifting testing landscape underscores the importance of tracking multiple disease metrics, including test positivity and daily hospitalizations.

Indeed, the latest tool for assessing local COVID-19 risks offered by the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention takes into account both local case rates and hospitalizations. On the other hand, this CDC measure — termed “community levels” — allows for scenarios in which testing may not adequately capture high rates of local transmission. Hospitalization trends can trigger a heightened risk assessment on their own under the new tool if they are severe enough.

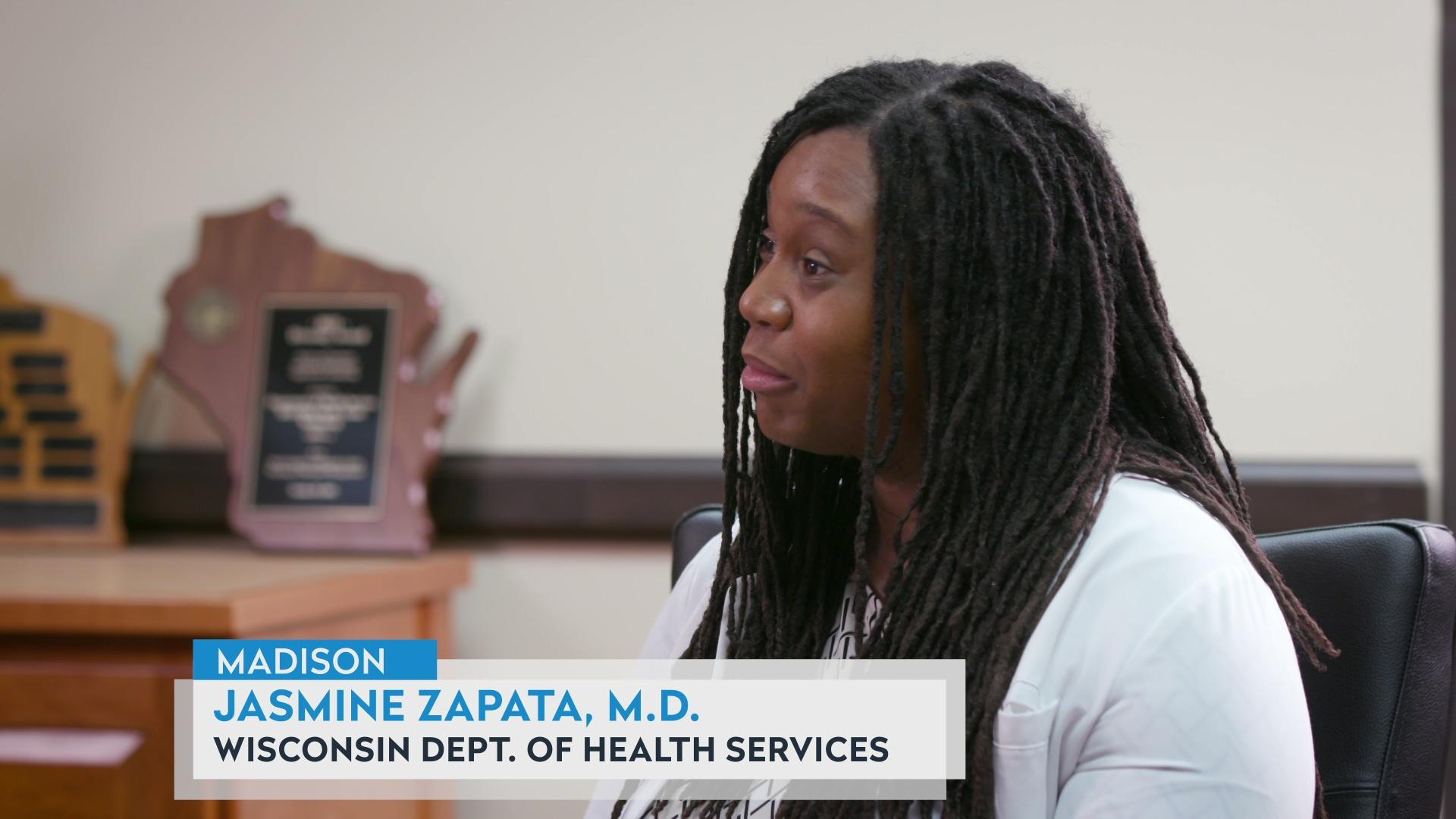

In Wisconsin, the state health department is continuing to emphasize the central role of testing in its COVID-19 response.

“DHS is committed to ensuring all Wisconsinites have access to testing services,” said Elizabeth Goodsitt, a department spokesperson, in an email to PBS Wisconsin. “We know testing is a critical tool in our efforts to stop the spread of COVID-19.”

Goodsitt pointed to programs such as the department’s free at-home PCR test collection kits and free community testing sites around the state.

For the time being, reported test results appear to continue to provide a reasonable view of transmission in Wisconsin. New COVID-19 cases have ticked up in the state in late March and early April 2022, in line with increasing virus levels in wastewater and a similar rise in test positivity.

At the same time, a sustained decline in covid-related hospitalizations is persisting — at least for the time being. The trajectory of COVID-19 hospitalizations has lagged trends in cases since the start of the pandemic, but this lag might be becoming more pronounced as widespread immunity — primarily through vaccination — slows not only transmission but the rate at which at-risk individuals become sick enough to require hospitalization, Sethi explained.

“We can have a lot of transmission, but we’re not necessarily going to see a subsequent rise in hospitalizations if all the cases were in people who are vaccinated and they’re most likely not going to require hospitalization,” he said.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us