What Karst Is, And How It Affects Wisconsin's Drinking Water

Any serious look at Wisconsin's geology and groundwater will at some point likely encounter the term "karst." The concept is hardly specific to Wisconsin, but it's helpful for understanding the land and drinking water across much of the state.

July 13, 2016

Cave of the Mounds stalactites

Any serious look at Wisconsin’s geology and groundwater will at some point likely encounter the term “karst.” The concept is hardly specific to Wisconsin, but it’s helpful for understanding the land and drinking water across much of the state.

Karst is a geological formation that results when naturally acidic rain or surface water seeps through soluble minerals in the bedrock underneath the topsoil. Most karst consists of limestone or dolomite — the latter predominates in Wisconsin. This long-term combination of water and minerals results in an underground landscape shot through with cracks, fissures and other fragmented characteristics.

The creation of karst can yield dramatic geologic features, from Wisconsin’s Cave of the Mounds to the striking “stone forests” of south China. When highly eroded karst causes the soil layer above it to give way, it creates a sinkhole. These depressions are but one of many different phenomena that occur in karst geology. A karst landscape is also conducive to the spread of environmental contaminants from the surface into groundwater.

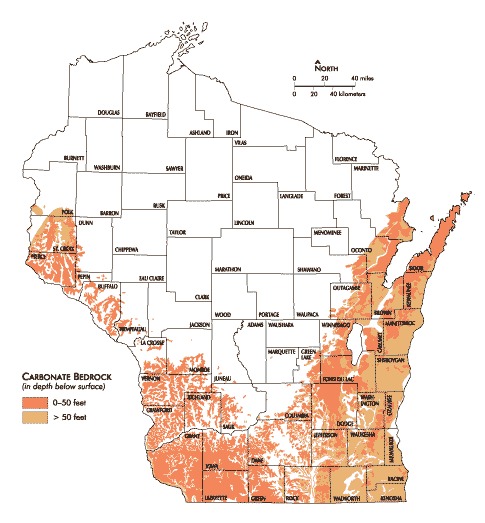

Karst geology underlies much of southern Wisconsin and extends northwards in a V shape along the eastern and western sides of the state. In the west, it accompanies the Mississippi River as far north as Polk County and includes a significant portion of southern Minnesota. Along Wisconsin’s Lake Michigan shore east, karst extends through southern Marinette County and into the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

A map from the Karst Waters Institute, a nonprofit research and educational organization, provides a broad overview of where this landscape is found across the United States. Wisconsin is certainly among the states where this geology most predominant, but it’s is far more dominant in Florida, where the entire state sits above one massive karst aquifer.

Comparing Florida and Wisconsin illustrates that not all karst geologies are equal. Florida, of course, is notorious for sinkholes that swallow cars, buildings and large trees, drain shallow lakes, and have sometimes even killed people. In Wisconsin, sinkholes are pesky and dangerous, but rarely so catastrophic. One reason for this difference is that Florida’s karst mostly consists of limestone, which dissolves more easily than the dolomite that predominates in Wisconsin. Considering Florida’s high humidity and frequent precipitation, that limestone can make for a much more volatile geology.

Groundwater Is Abundant But Fragile In Karst

In a porous karst landscape, water moves more easily between groundwater storage areas and surface water features like streams, lakes and rivers, meaning that contaminants that show up in groundwater are quicker to show up in surface water, and vice versa. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency sums up this dynamic: “In karst landscapes, the distinction between ground water and surface water is commonly blurry, and sometimes very tenuous. Groundwater may emerge as a spring, flow a short distance above ground, only to vanish in a disappearing stream, and perhaps re-emerge farther downstream again as surface water.” This process was one factor noted in a 2013 report that found nitrate levels going up in the Mississippi River.

Despite those disadvantages, karst is one of the reasons why Wisconsin is so rich in groundwater in the first place. A groundwater supply depends on rain and melting snow, but is also affected by where that water can flow. In a karst landscape, the extensive and interconnected network of fissures within soluble dolomite or limestone makes for an ideal storage system.

“It’s not true of every karst setting, but in the areas where we have karst, we have typically pretty good groundwater supplies,” said Madeline Gotkowitz, a hydrogeologist with the Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey.

In areas like north-central Wisconsin, the underlying geology is dominated by Precambrian rock like granite, quartzite, basalt, Gotkowitz explained. These rocks are less soluble in water, and don’t tend to form major fractures unless there’s an earthquake or unless humans fracture it deliberately with techniques like those used for oil and gas fracking. She said this geology causes problems in places like Taylor County, where agricultural operations have trouble expanding for lack of access to plentiful groundwater.

“It’s not that it rains any less there, it’s just that their aquifer doesn’t have the same level of storage,” Gotkowitz said. Without places to flow underground, precipitation instead runs off into streams and rivers.

Groundwater Concerns Vary Across Wisconsin

The behavior of karst itself also varies across Wisconsin, largely because of differences in the soil and sand that overlay the bedrock. As the landscape changes, so do potential contaminants and their potential to make their way into the water supply.

Soil can act as a natural filter, guarding against some contaminants and reducing the acidity that rainwater takes on when passing through the atmosphere. (Depending on the soil’s chemistry, it can also increase that acidity.) Thin soil offers more opportunities for water to erode the underlying dolomite, and it’s easier for contaminants from the surface to make their way into the groundwater. And despite bordering two Great Lakes, about two-thirds of Wisconsinites mostly rely on groundwater for their drinking water supply, according to the DNR, either through municipal water utilities or through largely unregulated private wells.

Major contaminants in groundwater include nitrate and manure-related pathogens (bacteria and viruses) from farms, more pathogens from septic systems leaking human waste, chemicals spilling from storage tanks and runoff from road salts. So while karst aquifers aren’t the only bedrock geologies vulnerable to groundwater contamination, they’re of particular concern when combined with thin soil and major agricultural or industrial activities.

Throughout Wisconsin, agricultural pollution is a major concern, especially in northeastern Wisconsin, where Door and Kewaunee counties have a karst landscape and relatively thin soil. Farmers in Wisconsin’s karst areas can end up polluting groundwater even when they’re taking the proper steps to control runoff, reported the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism in 2014. The issue has been building for years, with a 2007 report by the Northeast Wisconsin Karst Task Force (a collaboration of the University of Wisconsin-Extension and county conservationists in Brown, Calumet, Door, Kewaunee and Manitowoc counties) detailing the state of groundwater in the region at that time.

When geologists and water experts talk about karst, then, they’re talking about not a static feature of Wisconsin’s landscape, but a dynamic system with impacts that vary widely when affected by other geological factors and human actions.

“It’s dynamic at a geologic pace, not at a human-historical perspective,” Gotkowitz said. “I think farming practices change much more rapidly.”

To dig deeper into specific aspects of karst, the Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey provides background information about karst and sinkholes along with links to more resources about this geology in other states, and a pamphlet produced by UW-Extension and the Rock River Coalition offers tips to prevent groundwater contamination.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us