What happens when patients cannot afford 'specialty' drugs

Rx Uncovered: A Wisconsin man being treated for chronic lymphocytic leukemia seeks to understand why a cancer drug that costs $13,000 a month would not be covered by his self-funded health plan.

By Marisa Wojcik | Here & Now

July 18, 2025

A Wisconsin man asks why a cancer drug would not be covered by his health plan.

For decades, the cost of prescription medications has been ever increasing. At the same time, health coverage of these medications has been decreasing, forcing patients to make harder decisions about their health. Rx Uncovered is a series from “Here & Now” producer Marisa Wojcik that dives into the complex systems driving these trends and the stories of patients facing life or death choices. The second story is about a leukemia patient who had a promising treatment that cost the same as buying a house, and he couldn’t access it without paying up front.

“All of a sudden. my numbers were at like 167,000 compared to like 4-5,000, said Kevin Voltz, who has what’s called chronic lymphocytic leukemia, or CLL — a type of blood cancer. He was suddenly in urgent need of treatment.

“My cancer center — I can’t say enough about them,” he said.

Voltz’s oncologist had a prescription that was promising, but it came at a price.

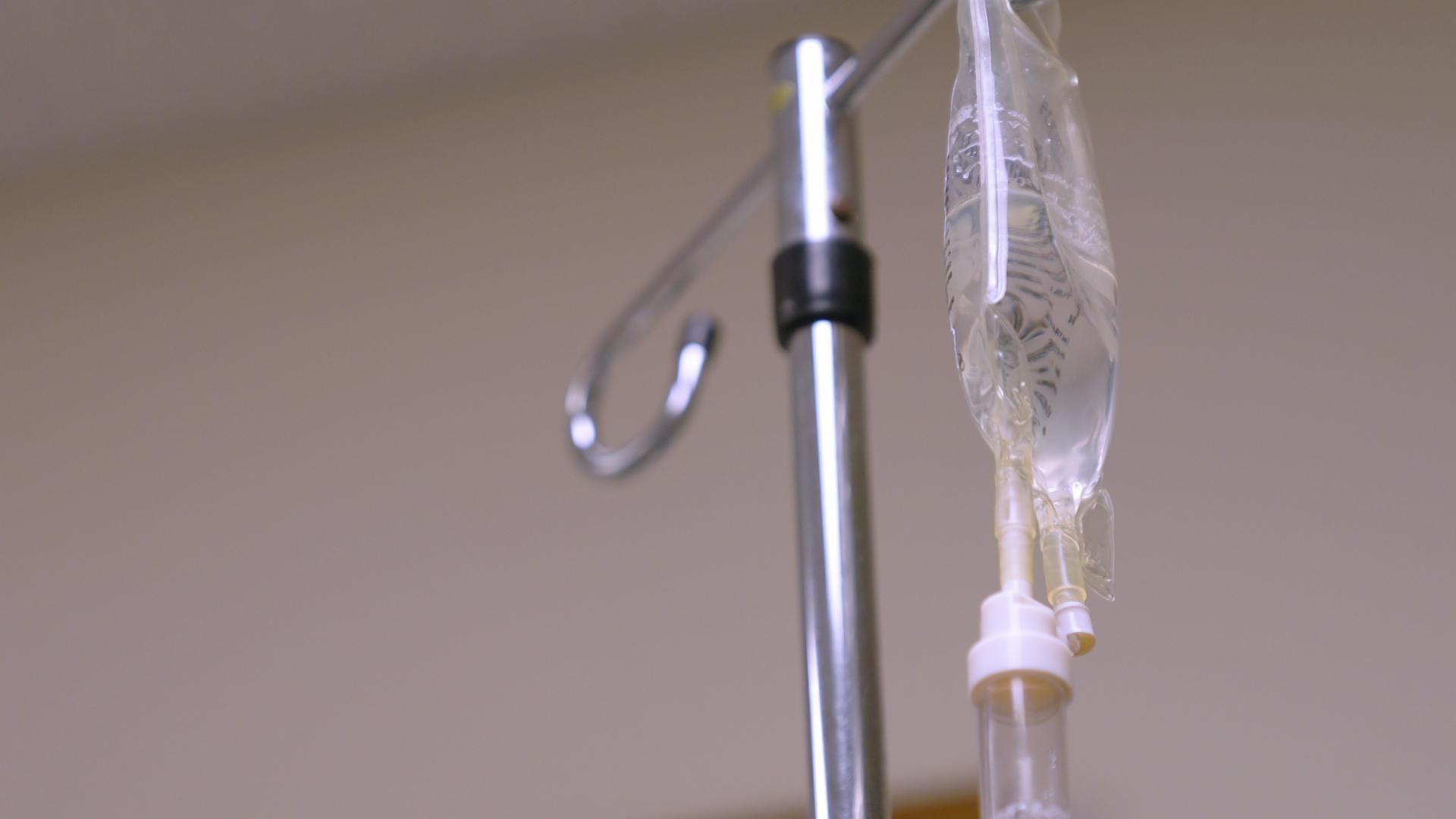

“She said, ‘We need $13,000 before we can ship this.’ And I said, ‘$13,000?’ ‘Yes, that’s what this drug costs to be delivered without insurance,'” Voltz recalled.

He soon discovered his health plan wouldn’t be covering a dime of his medication, calling it a non-preferred-speciality drug — and putting him on the hook for 100% of the cost.

“Nobody could do that. I don’t care who you are. Voltz said.

This specialty drug cost $13,000 per month. It’s a non-chemotherapy treatment and the first FDA-approved medicine for people with a “high-risk” form of CLL — with no generic equivalent. Voltz’s clinic pleaded with his health plan to cover some portion of his life-saving medication.

“They got lots of denial letters and stuff over the months saying that there was nothing they could do,” he said. “And I’m running low on my month’s supply. And what am I going to do next month?”

Under the Affordable Care Act, health insurance plans have cost-sharing requirements and limits to what a patient has to pay out of pocket. Covering prescription drugs is considered an essential health benefit.

However, Voltz’s health plan doesn’t fall under the ACA, because it’s not technically insurance. Instead, his health coverage through his employer is what’s called a self-funded plan.

These plans are also known as self-insured, which is a misnomer.

“We don’t cover that because we’re a self-funded insurance company,” Volz said.

“A self-funded plan is not insurance,” said Sarah Davis, who is the director of the Center for Patient Partnerships, a research and advocacy program at UW-Madison.

“Being insurance is what triggers state regulation, and there are rules those companies need to follow in terms of mandatory benefits they need to cover,” she said.” If there are claims being denied, the protections that that consumer has are reduced in self-funded plans.”

In 2025, self-funded plans are the most predominant form of health coverage in the United States, and it’s because they help employers save money.

“Self-funding lets the employer take control of the second or third biggest line item on their budget. The last few years — that’s been a double-digit increase,” said Mike Roche, who is the director of business development at The Alliance, a Wisconsin organization that helps employers design self-funded health plans.

“If you’re not trying to manage it and you’re fully insured, you’re going to get an increase probably every year. The last few years, that’s been a double-digit increase, and it’s getting more and more difficult for employers to find a way to control that cost,” he explained. “The last few years, that’s been a double-digit increase, and it’s getting more and more difficult for employers to find a way to control that cost.”

Those increases make it difficult for employers to afford health coverage. A December 2024 study issued by Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce shows the top issue for Wisconsin businesses is to “make health care more affordable.”

“The reason that self-funded plans came about is that employers realized they were paying a fixed amount to the insurance company, and then it was the insurance company that while holding the risk could make the profit. And so employers realized, hey, if we hold all that money ourselves and only pay a percentage in claims, we’re keeping that profit,” she explained. “The concern I have as a health advocate is that a large motivation for having a self-funded plan is to save money, and the place that the money is saved is in paying out less claims.”

But it’s often difficult for people to even know what kind of plan they have.

“It takes advocates and patients sometimes quite a bit of time to parse out and figure out that it is not insurance,” Davis said.

“I think a lot of it comes back to transparency,” Roche said.”What employees need to know is that your employer has now become the insurance company.

He went into further detail.

“Whether you’re fully insured or self-funded, that plan doc is the same. I think as long as an employee understands the high-level pieces of their plan design — deductibles, co-insurances, what’s on their formulary list and their PBM, who’s in network from a doctor and hospital standpoint — that’s going to cover 95% to 98% of everything they do during the year,” he said.

That same study found the majority of people in Wisconsin are very worried about the cost of health care.

So, who pays for the big-ticket items?

“There’s a couple of drugs coming out. They’re going to be $3 million a piece,” said Roche. “How am I gonna cover those? And how does that trickle down to the Humeras and the Stellaras that folks need on a more regular basis, but are still thousands of dollars a month?”

Advocates say self-funded plans can create a conflict of interest for employers who suddenly have an employee with expensive health needs

“Maybe you could check into going part time and see if Medicare or something would help out,” Voltz recalled hearing from his employer. “Really? I thought to myself — really? You want me to go part time? Now I’m going to lose benefits. I’m going to lose my insurance and I’m going to be part time. Is this a way to weed me out eventually?”

Davis compared incentives between the two types of coverage.

“So, in an insurance situation, the employer wants to protect the employee, right? They want to get the most for their money,” she said. “Once we’re in a self-funded situation, the employee is at odds with the employer.”

The side effects of dealing with the situation took a toll on Voltz.

“One day, I sat on my phone on hold from one of the drug companies for over six hours. And they kept coming back and saying, we’ll be right with you,” he recalled, “and just stressing me out to the point where I was not paying attention to my healing.”

Advocates at his clinic didn’t let up, exhausting every possible avenue to access the medicine.

“They’re very persistent — very persistent,” said Voltz.

After months of setbacks, good news arrived from his clinic.

“She kept calling me and calling me and calling me,” Voltz said, “and she couldn’t tell me the news fast enough that they had come through.”

The drug manufacturer said they were going to provide the remaining dosage of his treatment, at no cost.

‘I don’t think anybody should have to fight for their life like that. It’s hard enough just to sit back and think about me not being here for the people around me,” said Voltz. “I worry about not being here.”]

Davis described her worries as well.

“I worry for people don’t have hours and hours and hours to read fine print, and make sure that they’re going to get what they need if they get ill,” she said.

In the end, Voltz hopes some good will come from his experience.

“My dad died from CLL several years ago.He would go and have spinal taps and stuff,” Voltz recalled, “and he always said ‘If they can learn something from my treatments for the next people, I’ve accomplished something in life.'”

Voltz emphasized he feels the same way: “I say the same thing. If they can get something out of me for other people, I’ve done exactly what I wanted to do in life.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us