What Did Wisconsin's Farm-To-School Coordinator Accomplish?

As the state of Wisconsin considers eliminating funding for the farm-to-school coordinator position at the Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection in its 2017-19 budget cycle, advocates fear they'll lose a crucial leg up for farmers and school districts.

April 12, 2017

Bruschetta garden at Toki Middle School in Madison

As the state of Wisconsin considers eliminating funding for the farm-to-school coordinator position at the Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection in its 2017-19 budget cycle, advocates fear they’ll lose a crucial leg up for farmers and school districts.

The currently vacant position would cost the state about $66,400 per year in minimum salary and benefits when filled, said DATCP spokesperson Bill Cosh. People who work on farm-to-school programs in Wisconsin say the role of the position they’ve found most valuable is how it can help schools in various situations figure out the logistics of starting and expanding their efforts in this arena.

Districts with farm-to-school programs often have to go through some supply-chain gymnastics even to get vegetables, fruit or milk from area farms to their cafeterias. The School District of Holmen in western Wisconsin even raises some of its own chicken meat, though most aren’t quite that ambitious. It’s when districts are figuring out their particular needs that they tend to turn to the statewide coordinator at DATCP.

Mike Gasper, nutrition director for the Holmen district, said the previous and only coordinator helped him figure out how chickens his students raised could be processed and served while complying with health and safety regulations.

“There were all those resources that were able to help us figure out the steps we had to take in order to make this happen,” Gasper said. “I have to give a lot of credit to DPI and the farm to school coordinator… I think that position is so valuable for the $86,000 that was budgeted for it. The amount of money that that position is ultimately responsible for bringing into the local economy is tremendous.”

The Wisconsin Legislature created DATCP’s farm-to-school coordinator position and accompanying program with 2009 Act 293, but didn’t fund the job until the 2011-13 state budget, Cosh said. The position wasn’t filled until July 29, 2013, and that employee left on May 27, 2016 — the position has been vacant since, Cosh said.

For now, DATCP has a limited-term employee managing two programs funded by United States Department of Agriculture grants: a $56,000 Farm to Cafeteria grant, and a $19,000 farmer training grant.

“The work is subcontracted to UW-Madison Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems, various nonprofit community groups and consultants,” Cosh said. “These groups are eligible to apply for USDA grants. DATCP also manages an AmeriCorps grant of $191,000 used for school nutrition education, field trips, and school gardens. In the future, [the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction] will be managing this grant.”

The Department of Public Instruction also has its own staff members who work on farm-to-school projects.

Even though Governor Scott Walker’s proposed budget eliminates the DATCP coordinator position, Cosh noted that it does not defund the state’s farm-to-school efforts generally. He said other employees at the agency, including a separate local-foods coordinator, “will continue to work with producers, food distributors and processors to develop and expand markets for local products, including schools.”

Tom Evenson, a spokesperson for Walker, pointed out that the coordinator position is currently vacant and said farm-to-school and other local foods efforts in the state, some federally funded, will continue. Evenson also noted a statement DATCP Secretary Ben Brancel made to the state legislature’s Joint Finance Committee, indicating the agency proposed the cut as part of its response to 2015 Act 21. (This law requires state agencies to reduce their budget requests by 5 percent.) Brancel’s statement also pointed out DPI’s role in farm-to-school programs, and said that agency is “best positioned to work with the schools on nutrition education.”

According to farm-to-school advocates, the former coordinator helped the state and individual school districts secure at least $200,000 in federal grants. Cosh said DATCP doesn’t track the amount of grant money the farm-to-school coordinator helped acquire, and therefore could not corroborate this figure. However, he said the agency does keep track of people and organizations who reach out to the state for help with farm to school programs. On that front, DATCP gets about 50 inquiries per year from school districts, and hears from about 70 farmers per year.

“Most assistance provided to school districts is to refer questions to DPI staff who work with food service personnel, farm-to-school nutrition education, and school garden programs,” Cosh said. “Most of the questions asked by schools are about education or federal meal program requirements.”

Complications of starting farm-to-school programs

One reason the DATCP state coordinator position has been valuable is that a school district can’t always just ask its existing food providers to start carrying more local items, said Vanessa Herald of the Great Lakes Region Farm to School Network and the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems.

“There’s a huge demand, and that demand is really for schools and other institutions who want to be able to have access to Wisconsin-grown foods through the distribution systems that they’re already using,” she said.

Perhaps illustrating this limitation, the Benton School District, located in southwestern Wisconsin, responded to the USDA’s 2015 Farm To School Census that it sources food from major distributor Sysco. Specifically, the district noted the company defines local as “within the U.S.”

Most districts participating in farm to school programs define “local” foods as coming from within the state, or even more narrowly, as within 100 or 200 miles. But whatever distance food travels, a lot of the heavy lifting on farm-to-school programs is all about assembling a supply chain by connecting growers, processors and distributors.

Another reason assistance from a state coordinator is valuable, said Herald, is that it helps districts find ways to implement farm-to-school programs in a cost-effective way.

“One of the biggest barriers…is that Wisconsin-grown is more expensive, and what we’ve really learned is that there’s smart and efficient ways to incorporate Wisconsin-grown into food service — like taking advantage of product when it’s in season or super abundant, or cosmetically imperfect seconds,” she said. “There’s also a lot of really creative ways to take advantage of product when it’s in season and at a good cost and also balance your commodity spending.”

The logistics of farm to school also present a learning curve for the farmers. Emerald Meadows, an organic farm in Columbus, sells vegetables and fruit to the Columbus, Wisconsin Dells and Sauk Prairie school districts. Becky Breda, who runs the business side of the farm, said she found the DATCP coordinator helpful.

“It was new for all of us,” Breda said. “My husband and I know our farm…but we didn’t really know anything about farm to school until somebody reached out to us. The farm-to-school coordinator can connect all the different players.”

Breda, whose background is in early childhood education, has since become heavily involved in advocating for farm-to-school programs and childhood obesity prevention. As an activist, she’s urged legislators to get the DATCP coordinator position put back into the state budget. She also points out that the local food movement has potential to go beyond schools, from early childhood education providers to hospitals to prisons.

Of course, some schools had gardens and served some local produce before “farm to school” became a better-known phrase, but most progress has been in the past decade or so, said Natasha Smith of Madison-based food advocacy organization REAP Food Group. The organization estimates that Wisconsin schools now spend about $9 million per year on products from local farms.

Vanessa Herald said local ingredients can be a wise investment even if they end up costing a district more up front,because farm to school programs have been shown to increase the number of students who eat meals served at school. That means more revenue for districts from students who buy their lunches, and via state and federal reimbursement for free or reduced-price meal programs.

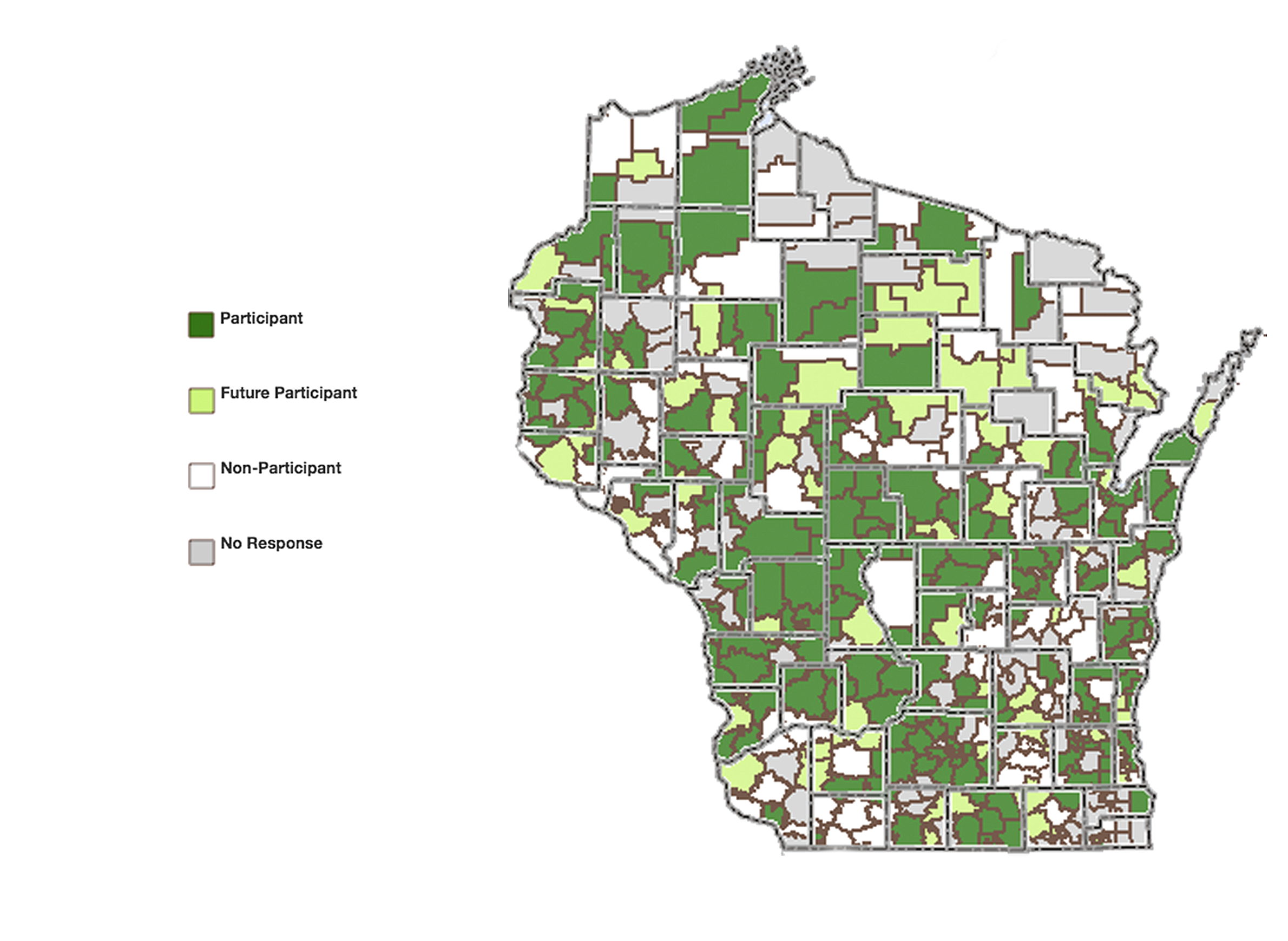

The farm-to-school concept has spread across the state, embraced by school districts both large and small, urban and rural. DATCP created a map, based on the Farm To School Census, the most thorough data-gathering project to date on farm-to-school efforts nationwide. The census reflects what schools were doing during the 2013-2014 school year — even then, though, 277 districts around Wisconsin reported implementing a farm-to-school project in one form or another. Additional schools reported that they planned to start engaging in these activities in the near future.

On DATCP’s map, a handful of counties show sparse participation, but farm to school generally has a diverse geographic reach around the state, with programs in more rural areas like Juneau, Washburn, Rusk and Polk counties, among many others. Most of the state’s big urban public school districts, including Milwaukee and Madison, have farm-to-school programs, but these districts account for less than half of the 565,559 students in Wisconsin that were participating in one way or another in 2013.

Based on a WisContext analysis of Farm To School Census responses, 164 districts reported spending money on local foods, 148 reported having at least one school garden and 211 reported having other farm to school learning activities (such as nutrition lessons and field trips).

Like other advocates, REAP is urging the state to continue funding the DATCP coordinator position. Smith believes that at the local level, farm to school is not at all a divisive political issue.

“Recently it’s kind of been politicized, even though it’s not a partisan issue and the benefits are not partisan benefits. But it has somehow been lumped to the left, which is not really accurate,” Smith said.

The geographic breadth of these programs speaks to interest in many corners of the state — farm to school is popular in left-leaning urban areas including Dane County and Milwaukee, but there’s also a lot of participation in more conservative rural areas, and even around increasingly urbanized but still relatively right-leaning areas like the Fox Valley and St. Croix County.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us