Wastewater surveillance for COVID-19 virus poised to detect future Wisconsin outbreaks

A statewide network that tracks coronavirus in sewage has served as a "leading indicator" of infections during the omicron wave of the pandemic, and while testing remains the primary method of surveillance, health agencies are working to continue refining this population-level tool.

By Will Cushman

January 25, 2022

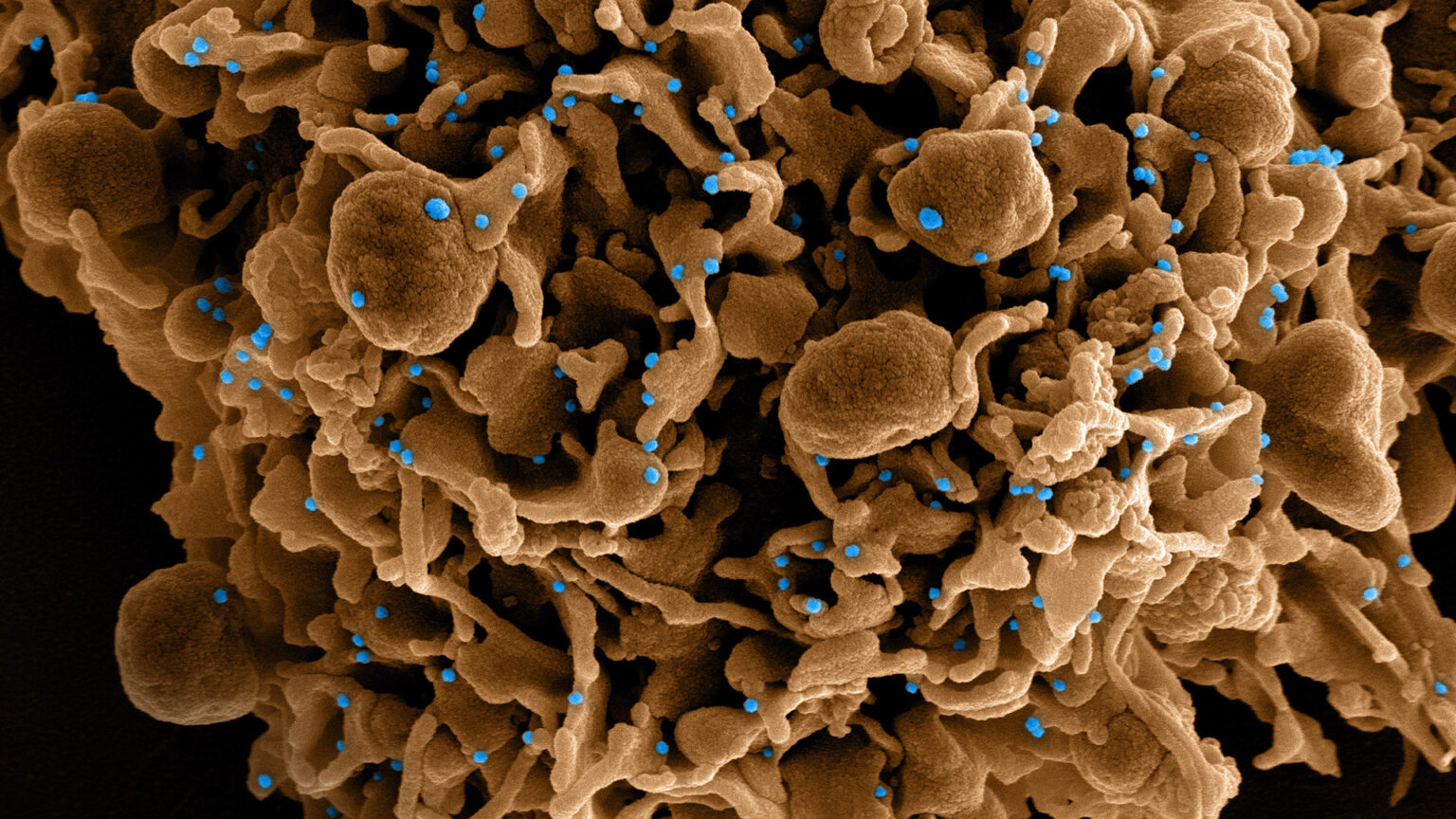

A colorized scanning electron micrograph shows a cell in brown infected with SARS-CoV-2 virus particles in blue, isolated from a patient sample. (Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases)

Of all the tools scientists have developed to take on COVID-19 — vaccines, treatments, medications, tests — one that has mostly evaded attention is wastewater surveillance.

Testing wastewater for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, has been touted as a potential early detection system for new outbreaks. People with active infections transmit SARS-CoV-2 via mucus and saliva that escapes their mouth and nose, but they also “shed” the virus in their excrement. These virus particles can hitch a ride in human feces whether or not someone who is infected develops symptoms of COVID-19.

The presence and amount of the virus in a community’s wastewater can therefore help gauge the prevalence of COVID-19 in that community — even if few people are getting tested.

Researchers have been testing community wastewater for SARS-CoV-2 since 2020 in many places, including Wisconsin, but this approach to surveillance received new attention in late 2021 and early 2022. That’s when the highly transmissible omicron variant spread rapidly around the globe, leaving many people with mild or asymptomatic infections and stressing the supply and availability of testing.

Gauging virus levels in sewage was able to track the trajectory of omicron infections around the United States, even as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention continues to work on a more organized network it’s calling the National Wastewater Surveillance System.

In Wisconsin, researchers at the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene partnered with the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences to begin testing wastewater samples for SARS-CoV-2 during summer 2020 in a project funded by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

Dr. Ryan Westergaard, state epidemiologist for communicable diseases, described wastewater surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 as a “surprising success” in the pandemic response during a Jan. 20 media briefing with state health officials.

“We haven’t used that type of technology for getting awareness of respiratory virus infections ever,” Westergaard said. “I wouldn’t say that it gives us better information than [tracking] cases, but it’s another dimension — another perspective — that we can use,” he said.

The Wisconsin Coronavirus Wastewater Monitoring Network offers the state’s major cities and small villages alike a free and voluntary method to track the silent spread of COVID-19 in their community. The state health department set a goal of including 100 “sewersheds” covering nearly 60% of Wisconsinites within the surveillance system. A sewershed is an area where raw sewage from homes and businesses are collected to a central treatment system. Some larger communities, like Milwaukee, are split into multiple sewersheds, while some sewersheds encompass multiple municipalities.

As of January 25, 2022, 46 sewersheds representing communities all across Wisconsin were actively participating in the state surveillance system, while an additional 22 were identified as inactive participants.

Residents in nearly all the state’s larger cities live in sewersheds participating in the system, including Milwaukee, Madison, Green Bay, Kenosha, Racine, Janesville, La Crosse, Appleton, Oshkosh, Eau Claire, Sheboygan and Wausau. Wastewater treatment facilities in dozens of smaller cities were also participating as of late January, including in Marinette, Merrill, Platteville, Portage and Superior.

Testing indicated that virus levels were decreasing in many of the sewersheds being monitored during the first weeks of January 2022, including Milwaukee, Madison, Green Bay, Kenosha, Racine and Janesville. However, virus levels increased over similar time periods in other places, including La Crosse and Superior.

Wastewater treatment facilities send samples for testing on their own schedules, which means the samples reflect trends over different periods of time. These differences mark one reason the state health department has indicated that wastewater surveillance shouldn’t be used to compare the amount of virus detected between communities at any given point in time. The agency instead recommends following trends over time.

Local health officials can use wastewater data from communities within their jurisdiction to help contextualize local infection trends. In theory, the wastewater surveillance could also serve as a “leading indicator” helping to foreshadow a rise or fall in local cases. However, health officials warned the present data are not robust enough to replace individual testing as the primary way to track outbreaks.

Morgan Finke, communications coordinator for Public Health Madison & Dane County, said the health department’s data team has described wastewater surveillance data as “very bouncy” and “somewhat difficult to interpret.”

Finke said the winter 2020-21 COVID-19 surge in local cases did not align very well with data coming from wastewater. On top of that, only some municipalities in the health department’s jurisdiction submit wastewater for testing, making it difficult to develop a thorough view of the virus’s presence within Dane County.

Instead, Finke pointed to what she described as consistent, accessible and abundant local options for testing in Dane County as having been sufficient for tracking local outbreaks.

“It’s possible our case data is more timely and relevant than in other locations where testing may be less accessible,” Finke said. “As such, in our experience, this data hasn’t served as an early warning of COVID surges compared to our case data, but that may be true for other areas.”

If testing and case data don’t provide a sufficient warning signal of an impending outbreak in the future, Finke said wastewater surveillance could help provide another tool.

However, “long term, it’s unclear how long this kind of surveillance will continue,” she said.

In early 2022, the CDC is “currently ramping-up efforts through partnerships with state, local, tribal and territorial health departments” to expand wastewater surveillance for SARS-CoV-2, according to an agency fact sheet.

Meanwhile, Dr. Ben Weston, chief health policy advisor for Milwaukee County, said during a Jan. 25 media briefing that he believed wastewater data would prove useful for keeping tabs on future outbreaks as public health agencies begin shifting out of crisis mode following the omicron surge.

“In the future, once we get into more of a surveillance mode with covid, which, remember, the acute phase of the pandemic is not forever … the sewershed data will be really valuable,” Weston said.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us