Tribal sovereignty at center of Wisconsin road dispute

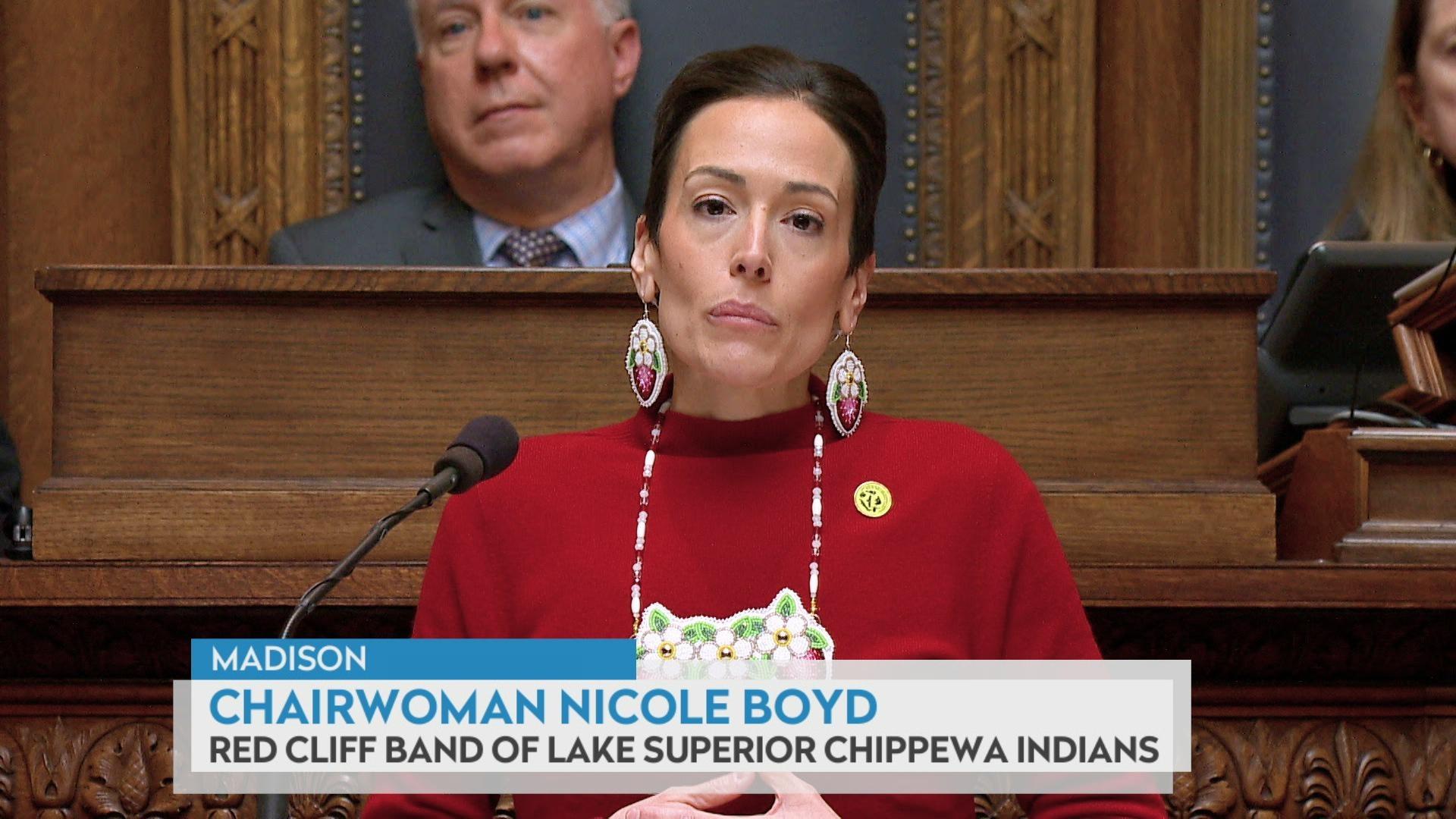

Tensions rise as 19th-century Indian policy divides community members over the rights-of-way for roads on Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa reservation lands in northern Wisconsin.

ICT News

February 17, 2025 • Northern Region

A sign marks a roadblock on Feb. 6, 2023, in the town of Lac du Flambeau. The U.S. Department of Justice filed a lawsuit on May 31, 2023, to force the northern Wisconsin town to pay unspecified damages for failing to renew road access easements with the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. (Credit: Courtesy of WJFW-TV)

This story was originally published by ICT, formerly Indian Country Today.

LAC DU FLAMBEAU, Wisconsin — Dave Kievet never dreamed he’d know so much about Indian land tenure, federal Indian policy and tribal history.

But as a non-Native homeowner living on one of four roads entangled in a dispute over right-of-way easements between the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians and a nearby town, he’s become a quick study.

He’s one of dozens of homeowners forced to use the roads through tribal lands to access their properties, and though he shares his neighbors’ frustrations over what seems to be a never-ending bureaucratic struggle, he has also gained understanding of the tribe’s position.

Now he’s convinced the solution to the problem should come at the national level.

“I firmly believe that Congress needs to step in and fix this,” he said. “They could buy back the land from the homeowners and give it back to the tribe.”

The dispute over the easements have been simmering for years, since the expirations began more than 10 years ago of four leases that had allowed nontribal members to access their properties by using roads that cross through tribal lands.

The easements are paid agreements in which the property owner — the Lac du Flambeau tribe — allows nonmembers to use the roads.

After more than a decade of failed negotiations over renewing the easements with property title companies and the town of Lac du Flambeau, however, tribal council members voted to set up barriers along the roads on Jan. 30, 2023.

The barricades — chains strung between two concrete blocks — prevented homeowners from driving to and from their properties. The blockade shocked town residents, and homeowners took their case to the media and lawmakers. The outcry was immediate: How could an obscure 19th century Indian policy — the Dawes Act — block taxpaying property owners from their homes in a respectable vacation community?

A federal judge refused to force the tribe to open the roads in response to a lawsuit brought by homeowners, but the tribe agreed to temporarily open the roads in exchange for monthly payments from the city.

Now the dispute is tangled up in federal court, the new Trump administration apparently has blocked the federal government’s ability to grant easements until further notice, and property owners are uncertain about their homes nestled among the lakes in northern Wisconsin. Interior Department officials did not respond for comment.

John Johnson, president of the Lac du Flambeau tribe, said the temporary deal provides a window of opportunity for the town and title companies to make a viable offer to renew the easements.

“To be crystal clear, the tribe still expects compensation for unauthorized land use and disregard of our private property,” Johnson said in a statement. “This includes expenses incurred over 10 years as well as terms to protect tribal lands from unauthorized use, so future generations of tribal membership can live peacefully without worry.”

History comes full circle

About 70 homeowners live in the nicely kept neighborhood built in the 1960s in the Town of Lac du Flambeau.

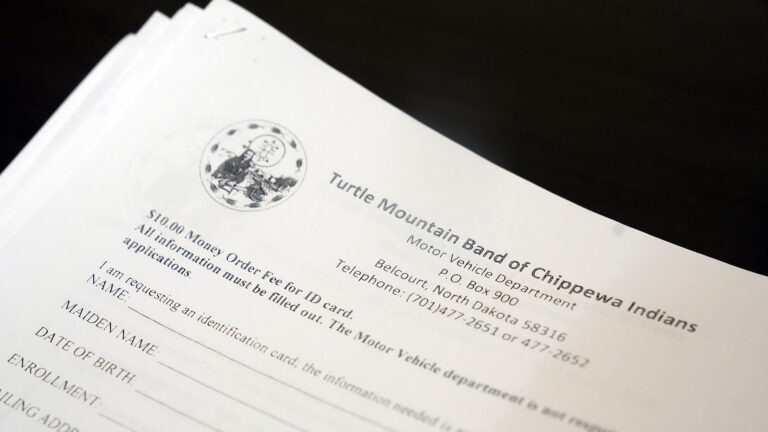

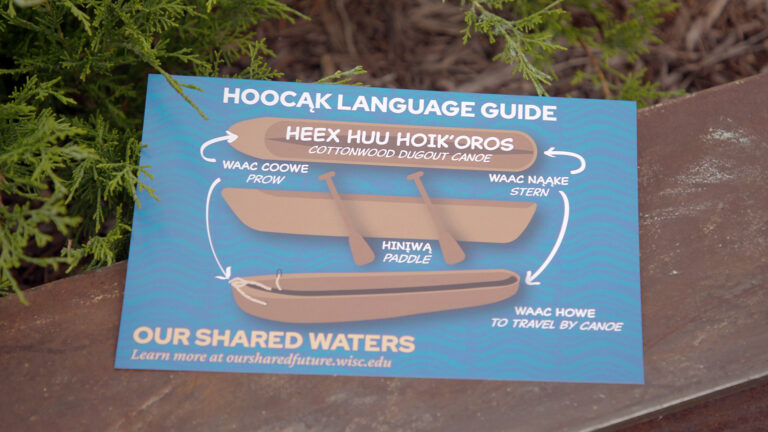

Before the roads were briefly barricaded in 2023, the homeowners knew little about the easement issue that springs from the Indian Allotment Act, known as the Dawes Act, a 19th century federal Indian policy that granted allotments to individual Native people in an effort to break up large tribal land holdings.

The act also allowed the federal government to open up what they described as excess or unallotted tribal lands to homesteaders. Poverty forced many Native allottees to sell their lands and much was lost for failure to pay taxes. By the time allotment ended in 1934, Native people had lost more than 90 million acres across the country.

For Native Americans, the pain and trauma from such epic land losses remain today. But for the non-Native people around Lac du Flambeau, like most Americans, the policies negotiated by their forebears are part of a vague, long-ago past that has little impact on their lives today.

The residents along the roads in question, however, soon found out that federal Indian policy is ancient history – until it isn’t.

Corporations and communities across the U.S. have faced similar situations in recent years. Many of the now-expired easements and lease agreements involving use of tribal lands were negotiated in the 1960s and 1970s, and most were conveyed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs without consultation with tribes.

At the time, the negotiations and payments were largely perfunctory. When property developers began building the Lac du Flambeau homes in question, for example, they paid the BIA $88 for the original 50-year easements.

Limited resources prevented tribal leaders from taking action. But those days are over.

In January 2023, the Lac du Flambeau tribe blocked access to the roads and notified the title companies, town and property owners that the tribe wanted $20 million to remove the barricades and secure a 25-year right-of-way agreement. The money, they said, would pay for attorney’s fees and a decade of trespassing.

In February, the homeowners filed suit against the Lac du Flambeau Tribal Council seeking access to the properties. The tribe opened the roads a few weeks later by granting temporary access permits to the Town of Lac du Flambeau in exchange for monthly payments from the town. Those payments ended in August 2024 when the town said it had exhausted its $600,000 road budget paying for the temporary permits, according to federal court documents.

By then, the federal government — acting at the direction of then-Interior Secretary Deb Haaland and the U.S. attorney general – had filed its own lawsuit against the Town of Lac Du Flambeau in May 2023 on behalf of the tribe and tribal allottees. The suit accuses the town of illegally trespassing on lands held in trust by the U.S.

The town has maintained the roadways over the years, but the original easements began expiring in 2011, with the last easement expiring in February 2018, according to court documents.

Earlier in 2025, U.S. District Judge William Conley issued an order affirming that the roadways should not be blocked while the cases were pending. Trial is set for May 19.

‘Land Back’ efforts

Expired easements and leases like those in Lac du Flambeau are representing new opportunities for tribes to exercise sovereignty, according to the Indian Land Tenure Foundation.

Johnson agrees. In an interview with the Wausau Pilot and Review, he said renegotiating the leases is part of a broader effort among tribes to exert sovereignty.

“It’s happened in different states already,” Johnson said. “We just want what’s ours and we want to protect it.”

Monte Mills, director of the Native American Law Center at the University of Washington School of Law, told the Wausau Pilot and Review that federal policy is more supportive of tribal self-determination and sovereignty in recent years. Today, negotiations for leases and rights-of-way through tribal lands require consultation with tribes involved.

The Land Back movement, which began gaining traction around 2019, has been advocating for the return of Indigenous lands globally. In 2024, the Yurok Tribe in California entered into a co-management agreement with the National Park Service and California State Parks for a 125-acre stretch of land to be returned to the tribe in 2026.

“Give the land back to the first people as stewards of the lands,” said Yurok Chairman Joseph James. “We know how to protect, to preserve and to take care of our land. This is what it looks like when we talk about land coming back to Indigenous people.”

And the U.S. Department of the Interior returned three million acres of land to tribes through its Land Buy-Back Program that consolidates land and places it into trust for tribes.

Local officials had been in discussions about the possibility of returning land back to the tribe as a means of settling the easement dispute. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported in August 2024 that Lac du Flambeau town leaders have asked state officials about the possibility, and held a special public meeting to ask Tom German, executive secretary of the state Board of Commission of Public Lands if such a thing were possible.

The state board was created in 1848 to manage 1.5 million acres given to the state by the federal government. Much of that land was taken from Ojibwe tribes including the Lac du Flambeau tribe. Today, the board manages about 75,000 acres of land including some near the Lac du Flambeau reservation.

Johnson has indicated in the past that the tribe is interested in getting land back.

Caught in the middle

Kievet, who bought his home in Lac du Flambeau about 10 years ago, is among the non-Native homeowners whose access to their homes was cut off in 2023 by the tribe’s road closures.

“We felt blindsided,” Kievet told ICT. “The sheriff came by and delivered a note saying the tribe was going to close down the roads and then they closed them the next day. We got exactly one day’s notice before they barricaded them.”

Homeowners were worried about their health and safety, he said.

“People wondered what would happen during an emergency,” he said.

In a press release, tribal leaders offered assurances that residents would have continued access to emergency services, mail delivery and waste disposal services. Leaders also detailed how tribal staff had reached out to residents with food and medicine deliveries and conducted wellness checks.

“They weren’t blocked off from the world, we took very good care of them,” Johnson told ICT in a November 2024 interview.

According to Johnson, the tribal police chief opened gates for residents when they had doctors’ appointments or needed medicines.

“To me, this is unbelievable,” Kievet said. “I’m being held hostage on my property and no one seems to care.”

‘Rising tensions’

After the lawsuits were filed, community discussion turned heated. On its website, town leaders of Lac du Flambeau pleaded with citizens to tone down negative comments about the tribe on social media.

‘The posting of disrespectful and/or intolerant messages only inflames emotions during a time when reason, common sense, and mutual respect must prevail, if resolution is to be achieved,” they wrote in a public statement,

Homeowners turned to their state lawmakers. State Sen. Mary Felzkowski, a Republican from Tomahawk, and state Rep. Rob Swearingen, a Republican from Rhinelander, called on Wisconsin’s Democratic Gov. Tony Evers to find a peaceful solution.

Felzkowski and Swearingen issued a joint press release that cited “rising tensions” and a need to “deescalate” the situation.

“We cannot stress enough how vital it is for the governor to use all the tools at his disposal to find a peaceful resolution,” they said in the statement. “With physical barriers going upon the roads used by residents, and rhetoric turning negative very quickly, it’s imperative that action be taken immediately to ensure the safety of citizens who are not to blame for the current situation.”

Felzkowski attended a Lac du Flambeau town meeting intended to resolve the issue, during which she said the homeowners were being held hostage and compared the tribe to terrorists, according to the Tomahawk Leader.

Tribal leaders responded by officially banishing her from the reservation.

Felzkowski said later that she regretted that “she contributed to the narrative of division in this muddy conflict,” but noted that she “didn’t regret speaking up for her constituents.”

In response to ICT’s request for comment about the situation, Felzkowski’s press director Cameil Bowler sent a statement on behalf of the senator.

“I am continuing to monitor the situation and work closely with involved parties including our federal partners,” according to the statement. “Ensuring that homeowners have access to their properties is necessary and I am hopeful that the dispute can be solved in a timely and respectful manner.”

The governor later visited the reservation to discuss the matter with tribal leaders.

“As this is an ongoing private dispute, my priority as governor is encouraging everyone in the area to engage amicably and peacefully to resolve this issue quickly,” Evers said.

Johnson and council leaders say they understand their neighbors’ anger and confusion.

“We feel for the individual property owners impacted by the title companies’ refusal to negotiate in good faith over the course of 10 years,” Johnson said in a written statement. “The tribe is fed up with the title companies’ games. Title companies could have settled the situation by paying a fraction of what is being asked now.”

Although the tribe took down the barricades, the disagreement, at times contentious and emotional, continues.

Complicated laws and policies

In its typically restrained style, The New York Times described the Lac du Flambeau situation as “complicated.” An understatement if there ever was one.

Town leaders and homeowners maintain they were not aware they needed to take action to renew the easements.

Kievet told ICT that when he purchased his home and property more than 10 years ago he was not aware of an easement that might block access to his home. Many of the houses are built along lakeshores, with some appraised at more than $500,000, in this well-known tourist community of upscale retirement and vacation homes.

But since the easement dispute, according to Kievet, property values have plunged as much as 85 percent.

“My position is that I didn’t do anything wrong,” Kievet said. “I bought my property in fee simple; I have documentation that shows these roads are public.”

But during a meeting in June 2024, town board supervisor Bob Hanson admitted town leaders believed that the title companies were taking care of the easement renewals.

“And they did not,” Hanson said. “I’m including myself in this. We as a board did not follow up to make sure they were doing it.”

A title company that was involved in the dispute offered the tribe more than $1 million to settle the issue, but also demanded the tribe extend easements in perpetuity, Johnson said.

Company representatives claim they followed the BIA process. This, however, runs counter to federal law as well as the tribe’s constitution, which limits easement agreements to 25 years, according to Johnson.

“They told us, ‘It’s forever or nothing,'” Johnson told ICT. “We can’t even give forever permits to tribal members.”

Johnson said the town and companies have disregarded the tribe’s sovereignty, which allows them to enforce laws and regulations “to preserve and protect the 12-by-12-square-mile reservation we have remaining after ceding millions of acres of land to the federal government.”

Johnson expressed disgust with the federal government’s repeated admonishments to mediate with the town and title companies.

“There’s nothing to mediate,” he said. “We’re sick of getting pushed around all the time. How many times did someone on our reservation lose land because they couldn’t pay taxes? Then it got sold off from underneath them.”

Earlier in 2025, the tribe announced they would once again erect barricades along the roads only to reverse themselves after a federal judge ordered the roads remain open while the situation plays out.

The judge issued an amended injunction instructing the federal government to take immediate action to prevent any effort to restrict access to the four roads. He encouraged the tribe to remove any barriers and refrain from imposing any additional restrictions. The tribe, however, issued a statement that officials would be issuing citations to those trespassing on the roads.

Neither the Town of Lac du Flambeau nor the tribe responded to emails asking about the citations. Kievet, who runs a Facebook page, “Behind the Barriers,” said he hasn’t heard of anyone yet receiving a citation. In a recent meeting, according to Kievet, an attorney for the Department of Justice instructed homeowners receiving citations to alert the agency.

Kievet said his research into the history of the tribe and federal Indian policy has helped him understand how the situation has gotten so contentious.

“I understand more about how things happened and I even understand the tribe being angry; I empathize with them,” he said. “But they’ve chosen to take it out on the wrong people.”

The fact is, according to Kievet, the federal government created the problem when officials created the Dawes Act.

Since President Donald Trump took office in January, however, a solution to the easement problem is likely to be put on hold for at least another 60 days.

On Jan. 20, 2025, the acting Secretary of the Interior Walter Cruickshank issued a temporary suspension of delegated authority for the Department of the Interior. Under the suspension, the agency is prevented from issuing any easements or leases related to the National Environmental Policy Act. This is in accordance with limits the president is seeking related to federal environmental policy. The agency did not respond to an email asking for clarification.

Looking ahead

Kievet told ICT that he believes discussions are still underway for perhaps a land-back deal that could solve the easement dispute.

Neither the tribe nor the town responded to emails from ICT asking about the proposal, but Kievet said he hopes to hear more in coming weeks.

The lawsuits are continuing as well, but the issues could be complicated by the new presidential administration. U.S. government lawyers on Feb. 5 sought an extension of deadlines to allow time for the Trump administration to review the case.

In Wisconsin, meanwhile, tensions remain high, with warnings that citations could be issued for those who use the roadways.

But the roads, for now, remain open to traffic as opposing parties work to resolve the issues. Kievet believes a final resolution needs to come at the federal level.

“Trying to make people solve this at the local and tribal level,” he said, “is too fraught and emotional.”

The Associated Press contributed to this article.

ICT, formerly Indian Country Today, is a nonprofit news organization that covers the Indigenous world with a daily digital platform and news broadcast with international viewership. Sign up here for ICT’s free newsletter.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us