The Path Towards Peak Population In Rural Wisconsin

They're older and aging faster, and persistently whiter than Wisconsin as a whole. More people are moving out than in. In some, deaths are already eclipsing births.

September 20, 2016

Price County farmhouse lens flare

They’re older and aging faster, and persistently whiter than Wisconsin as a whole. More people are moving out than in. In some, deaths are already eclipsing births.

They’re Wisconsin counties, and this is what they look like when they’re losing people.

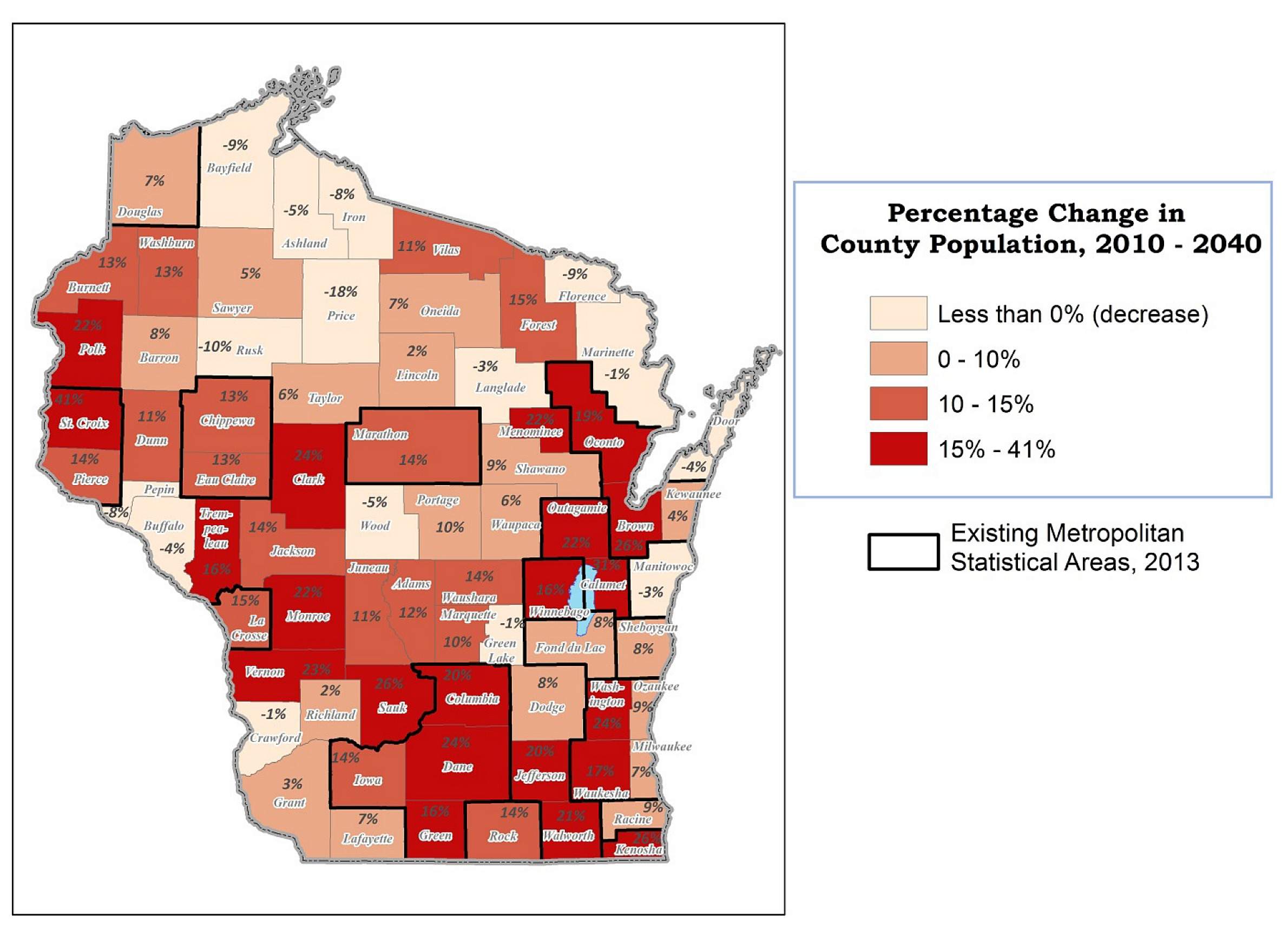

Currently at over 6.5 million people, the state’s population as a whole is still growing and could reach 7.7 million by 2040, according to a report issued by the University of Wisconsin Applied Population Laboratory. Much of the anticipated growth will happen in areas that already are heavily populated, especially the Madison area, the Fox Valley, Milwaukee’s suburbs and the Twin Cities’ exurbs near the St. Croix River. Over the same period, rural areas, especially those far removed from metro areas, will lose population, sometimes at significant rates.

The APL projected that 15 of Wisconsin’s 72 counties will have smaller populations in 2040 than they did in 2010. Nearly all of these counties are largely rural, with most in northern Wisconsin, relatively distant from the state’s largest cities and the nearby urban influence of the Twin Cities and Chicago.

These projections aren’t necessarily shocking — they line up with a trend of urbanization that has been ongoing in the U.S. since its founding. In this century, the growth of urban areas has continued around the nation, fed in part by the draw of cities for younger adults. But these changes are particularly dramatic for a state whose identity is so defined by rural life.

Demographers like the researchers at APL measure population change in terms of net migration (people moving in an area minus those moving out) and natural increase or decrease (the difference between births and deaths). Different areas that are losing population might show different combinations of these factors — i.e., some places might be losing people primarily to either death or migration, while other places might be seeing a convergence of both factors.

“You’d have to describe it as sort of a slow drip,” said David Egan-Robertson, an APL demographer and one of the report’s authors. The lab’s projections are partially based on extrapolating from past demographic trends, but also take into account the impact that aging populations have on different places. Rural areas are currently less likely to draw in new residents, so if more people are dying than being born — a negative natural increase — those locations will have a harder time making up for the population loss.

“In-migration tends to be focused in more metropolitan areas and cities,” noted Egan-Robertson.

For the sake of geographic diversity, the story of rural population loss around Wisconsin can be examined through what’s projected for three counties in different parts of the state: Price County, in north-central Wisconsin; Buffalo County, along the Mississippi River; and Manitowoc County, on Lake Michigan near Green Bay. Price County is projected to lose 18 percent of its population between 2010 and 2040 — the highest percentage decline in the state. Buffalo and Manitowoc counties face more modest losses of 3 and 4 percent, respectively. And in a state that is still about 87 percent white but gradually becoming more racially and ethnically diverse, each county is over 90 percent white.

Price, Buffalo and Manitowoc counties have plenty in common, but each demonstrates a slightly different way in which an area can shed population.

Price County

Population peak in 2010

Projections like those in the Applied Population Lab report are based partially on previous trends, and Price County in northern Wisconsin has been steadily shrinking population for years. Since the turn of the century, it has lost more than 2,000 people. People are dying faster than they’re being born in the county, but the bigger factor is that its residents are leaving. From 2000 to 2010, Price County had a negative net migration of 1,014 people. That’s a significant loss for a rural county whose population was about 14,365 in 2014.

But a negative natural increase can have a long-term undermining effect as well, especially in a place where dairy is a dominant industry. As deaths increase and the birth rate drops, that erodes the base of people forming new families in the area, which means there are fewer children to eventually inherit and continue the work on family farms. That’s a big concern, considering that 93.6 percent of Price County’s farms were family owned as of 2014, according to a UW-Extension fact sheet.

A lot of population growth around northern Wisconsin has in recent decades been driven by retirees from elsewhere in the state. That pattern could hold up well enough in places like Vilas County, Egan-Robertson said, but elsewhere in the region, the 2007-08 financial crash stymied the influx of retirees.

“With the recession happening, we noticed that all these counties that we just expected to continue to gain elderly people over the years, the flow just basically stopped,” he said. “That seems to be basically true now halfway through this decade.”

Price County is projected by the APL to lose 18 percent of its population between 2010 and 2040. That’s the largest loss of any Wisconsin county. More broadly, the lab’s projections place the county in a big swath of northern Wisconsin where several counties are expected to lose population over the next two-and-a-half decades, with a handful of other nearby counties growing, though mostly at modest rates.

This region already has a higher percentage of residents who are senior citizens (age 65 and older) than elsewhere around Wisconsin, and the APL expects that difference to grow more dramatic by 2040. In fact, the average age of almost the entire state will get a bit older, though northern Wisconsin will see the bulk of that change. Price County isn’t the oldest in the state, but it’s up there, with 22.1 percent of its residents senior citizens, compared to 14.4 percent for the state as a whole as of 2014.

Buffalo County

Population peak in 2010

Buffalo County is located between three growing areas of the state — the La Crosse area, the Eau Claire area, and the Twin Cities exurban growth centered in St. Croix County. But rather than driving up the population in Buffalo County, being at the center of that triangle seems to be drawing people away.

Residents in Buffalo County also feel the pull of a fourth city — Winona, Minnesota, which is just across the Mississippi River. A 2015 county profile from the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development indicated that while about 1,200 people lived in Buffalo County and crossed the river to work, only some 50 Minnesotans commuted in the opposite direction.

“Approximately 55 percent of Buffalo County’s employed residents work in another county or in another state,” the report noted. “This is an extremely high level of outu2010commute. The statewide average indicates 28 percent of workers commute out of the county in which they reside.”

Between 2000 and 2010, births stayed slightly ahead of deaths in Buffalo County, making for a natural increase of about 1.7 percent. But during that time, the county also saw a negative net migration of 3.3 percent, and the median age in the county increased from 39 to 44.

In some ways Buffalo County’s challenges with an aging population are similar to Price County’s: Farming provided about 2,700 jobs in the county in 2014, according to a UW-Extension fact sheet, and 86.7 percent of the county’s farms are owned by families or individuals. By comparison, the biggest non-farming source of employment was the trade, transportation, and utilities sector — a rather bulky catch-all the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics uses for several industries — which employed 1,383 people in 2014. This sector and agriculture overwhelmingly dominate the jobs picture in Buffalo County; the next largest sector, education and health, accounted for 679 jobs that year.

Manitowoc County

Population projected to peak in 2030

On the map of the APL’s projections, Manitowoc County looks like it’s being left behind by its neighbors. It’s entirely surrounded by counties that are expected to grow, especially in the Green Bay and Fox Cities areas to the west. Even small, rural Kewaunee County to the north is projected to get a modest 4 percent bump in population by 2040.

Between 2000 and 2010, Manitowoc County lost 1.8 percent of its population, which is now at 81,442 people. It had 789 more births than deaths over that decade, but also saw a net migration of negative 2,240.Unlike Price or Buffalo counties, though, Manitowoc could keep growing in population, or hold steady, until 2030. Egan-Robertson sees two main reasons for this difference: Manitowoc County has a more even age distribution, so the passing of the baby-boomer generation will take longer to affect it. The county also has more balance between agricultural and manufacturing jobs.

In 2014, about 10,000 Manitowoc County residents worked in manufacturing, according to a Wisconsin DWD profile. More than 5,000 county residents worked in agriculture that year, noted a UW-Extension fact sheet. Meanwhile, the DWD predicted manufacturing will grow slightly faster in Manitowoc County than it does in Wisconsin overall between 2012 and 2022, which may help to explain why the area may be a bit more resilient than Price and Buffalo counties.

Then again, those DWD projections were released before Manitowoc Crane announced that it would leave the county for Pennsylvania, taking more than 500 jobs with it. That accounts for about 5 percent of the county’s manufacturing jobs, and it highlights how much influence one company’s decision can have in areas dependent on the sector.

The demographic changes at work in Price, Buffalo, and Manitowoc counties illustrate some of the challenges rural areas face, but even urban and urbanizing areas in Wisconsin face some of the same issues. The primary demographic common thread across the state is aging. As stated in the APL report: “Whereas nearly half of the counties had fewer than 15 percent of their populations age 65 and over in 2010, and none had greater than 30 percent (the highest being 26 percent), by 2040 no county will have fewer than 15 percent of its population being elderly, and one-third will have elderly populations greater than 30 percent.”

Dramatic as these numbers may seem, Egan-Robertson pointed out that the news isn’t all bad for rural Wisconsin. The state’s population as a whole is relatively steady, currently not subject to huge spikes or sudden losses. Compared to other parts of the Midwest, rural areas in Wisconsin also tend to be a bit more economically diversified and therefore more resilient.

“Wisconsin does have some advantage in that there’s a lot of small manufacturing around in a lot of rural counties, which is holding on OK, and in some places it’s declining,” he said. “When you look in western Minnesota or the eastern Dakotas, you do have just this long pattern of people exiting, particularly in counties that are very agriculture-dependent.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us