Security Experts Warn Of Continuing Vulnerabilities In Wisconsin's Voting Systems

Before and immediately after the 2016 election, reports about malicious Russian activities drew attention to potential vulnerabilities in the voting infrastructure.

July 27, 2018

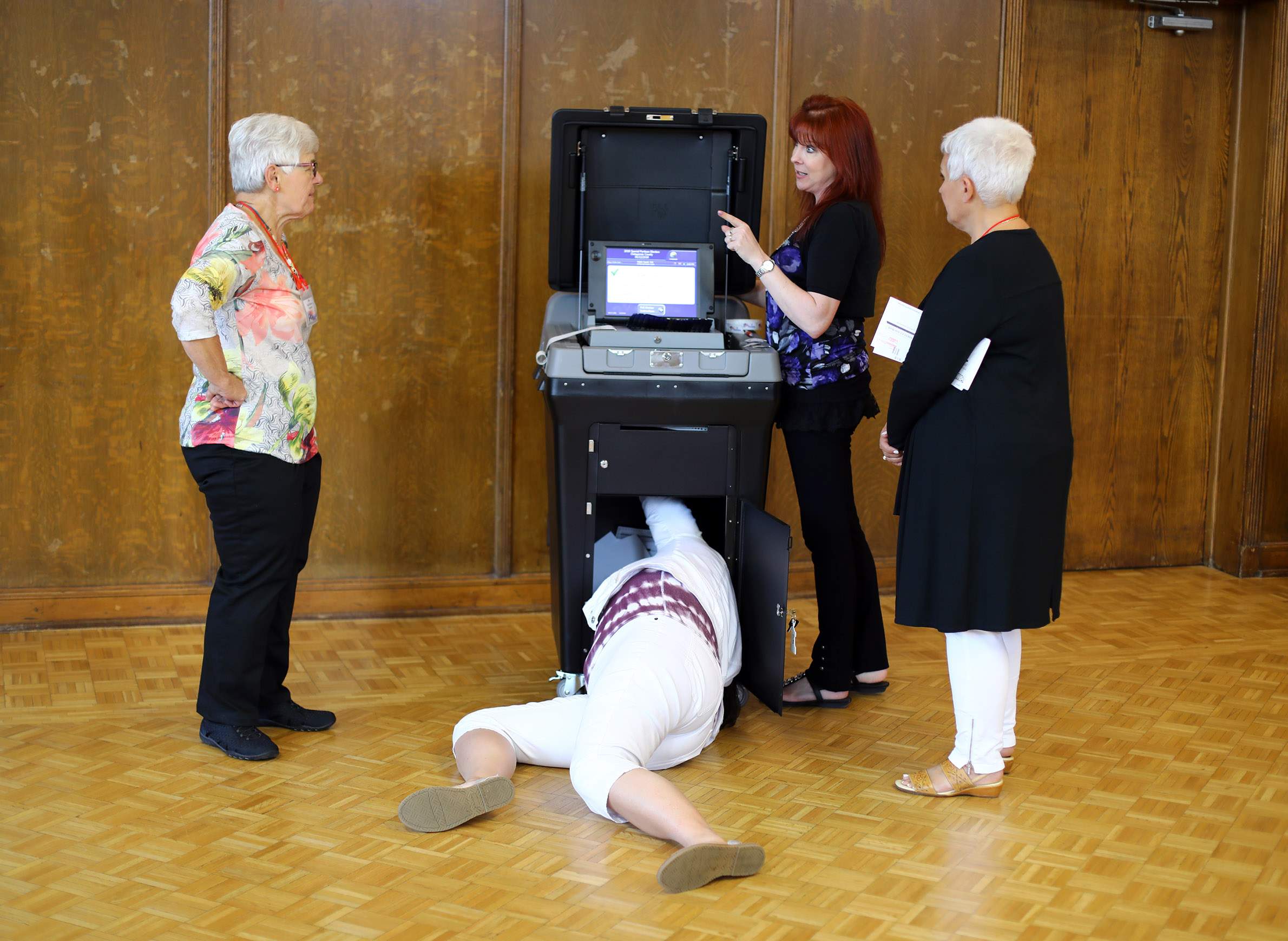

Voting machine at Little Chute village hall

Visiting Wisconsin on June 28, 2018, President Donald Trump tweeted “Russia continues to say they had nothing to do with Meddling in our Election!” It was not the first time the president cast doubt on Russian interference in the 2016 election, contradicting conclusions of the FBI, CIA and National Security Agency, as well as reports by bipartisan committees in both chambers of Congress.

But Russians have been testing the vulnerability of elections in Wisconsin and other states for years, and top U.S. intelligence officials have warned the 2018 midterm elections are a potential target of Russian cyberattacks and disinformation.

A key swing state, Wisconsin was the scene of Russian measures in 2016 that utilized social media and also probed the websites of government agencies.

Wisconsin and other battleground states including Pennsylvania were targeted by a sophisticated social media campaign, according to a University of Wisconsin-Madison study headed by journalism professor Young Mie Kim. This campaign tapped into divisive issues like race, gun control and gay and transgender rights. A Twitter account titled @MilwaukeeVoice and styled as a local news outlet was one of 2,752 now-deactivated Twitter bots and trolls — automated or human online fake personas — connected to Russia. Twitter vowed further purges of tens of millions of suspicious accounts.

Besides trying to influence Wisconsin voters through political ads and Twitter, alleged Kremlin-linked operatives also probed the website of the Democratic Party of Wisconsin. The websites of Ashland, Bayfield and Washburn counties in northern Wisconsin were targeted from Internet Protocol addresses listed in the joint FBI and Department of Homeland Security report on Russian malicious activity. And in July 2016, Russian government operatives attacked the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development website, state officials reported.

Early in May, the U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee issued a report finding that “in 2016, cyberactors affiliated with the Russian Government conducted an unprecedented, coordinated nationwide cyber-campaign against state election infrastructures.”

“Russian actors scanned databases for vulnerabilities, attempted intrusions, and in a small number of cases successfully penetrated a voter registration database,” the committee found. “This activity was part of a larger campaign to prepare to undermine confidence in the voting process. The Committee has not seen any evidence that vote tallies were manipulated or that voter registration information was deleted or modified.”

Such attempts continue. In a motion filed in court on June 12, Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s office wrote that “foreign intelligence services, particularly those of the Russian Federation … are continuing to engage in interference operations.”

Five top elections experts told the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism that Wisconsin’s voting systems are vulnerable. Some pointed to the Voting Machine Hacking Village demonstration in July 2017 at DEFCON, the annual cybersecurity conference held in Las Vegas. Hackers were set loose on more than two dozen voting machines used in the United States.

“By the end of the [four-day] conference, every piece of equipment in the Voting Village was effectively breached in some manner,” according to a report released after the conference. “Participants with little prior knowledge and only limited tools and resources were quite capable of undermining the confidentiality, integrity and availability of these systems.”

However, municipal and county clerks interviewed by the Center say they are not worried about a cyberattack, citing the fact that voting in Wisconsin is not centrally coordinated but conducted on a local level by 1,854 communities, large and small. They also note that the voting machines are not connected to the internet. As a result, many clerks resist proposals to conduct post-election audits, saying they have no resources for such efforts, which they consider unnecessary.

The fall 2018 statewide elections in Wisconsin are the primary on Aug. 14 and the general election on Nov. 6.

Throughout this year, the U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs chaired by Sen. Ron Johnson, Wisconsin’s Republican senator, has heard testimony from U.S. experts warning of Russia’s continued activities. Yet Johnson is not convinced it is a big problem.

In early July, Johnson visited Moscow with a GOP delegation. Returning home after meetings with Russian lawmakers and the foreign minister, Johnson suggested that to impose sanctions on Russia for the 2016 election meddling was an overreaction.

“The election interference … is not the greatest threat to our democracy. We’ve blown it way out of proportion,” he told the Washington Examiner.

Others are not so sure. The left-leaning Center for American Progress concluded in a report that Wisconsin’s “failure to carry out post-election audits that test the accuracy of election outcomes leaves the state open to undetected hacking and other Election Day problems.”

J. Alex Halderman, director of the University of Michigan’s Center for Computer Security and Society, agreed, saying “Rigorously auditing the outcome of the election is an essential safeguard against cyberattacks.”

Halderman was a driving force behind the 2016 recount of the presidential vote in Wisconsin, bankrolled by the campaign of Green Party candidate Jill Stein. Stein’s campaign is embroiled in a legal battle in Dane County Circuit Court for access to source code that it believes could reveal vulnerabilities in Wisconsin’s voting technology and to what extent the campaign’s findings should remain confidential. That case is pending.

Halderman was highly critical of claims that decentralization and diversity of systems would rule out a successful cyberattack.

“Diversity can be a strength, but in a statewide contest, I don’t have to hack all the machines,” Halderman said, citing Trump’s narrow 22,748-vote win in Wisconsin. “I just have to hack some machines.”

To illustrate his point: In 2011, a human error made by Waukesha County Clerk Kathy Nickolaus changed the outcome of a statewide Supreme Court election. Nickolaus said she forgot to hit “save” on a vote tally in a Microsoft database, failing to report 14,315 votes, according to an independent investigation of the incident. A recount followed, which switched the apparent winner from Joanne Kloppenburg to incumbent Justice David Prosser.

Recount confirms results, raises concerns

Before and immediately after the 2016 election, reports about malicious Russian activities drew attention to potential vulnerabilities in the voting infrastructure.

Jill Stein, who got just 1 percent of the vote in Wisconsin, requested a full recount of all ballots cast in three battleground states that gave a narrow victory to Trump — Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania. Wisconsin was the only state to authorize the recount.

Although it found no evidence of election tampering or foreign interference, the results uncovered thousands of miscounted votes. Most notable was in the city of Marinette, where a few outdated voting machines grossly miscounted votes, with one machine failing to count over 30 percent of the ballots.

“Our best estimate is that at least one in 117 votes [statewide] was miscounted, and probably more,” said Barry Burden, political science professor at the UW-Madison. Burden, who is a director of the UW’s Elections Research Center, led a study of the 2016 recount.

“As a voter, to think that there’s one in a hundred chance that my ballot would be miscounted — that would be alarming,” Burden said.

But many Wisconsin election officials say the concern is overblown.

Stein’s request “was an abuse of the recount prerogative, born of the irrational belief that Wisconsin’s highly decentralized and secure elections infrastructure is vulnerable to the kind of meddling that might overturn the will of the voters,”Dane County Clerk Scott McDonell wrote in a Wisconsin State Journal op-ed.

McDonell told the Center he is not particularly worried about election tampering in Wisconsin. “Even now with what happened with Russians intentionally trying to affect the election, I’m still more worried about a tornado or flood.”

State law has since been changed to prohibit candidates who lose by more than 1 percent of the vote from forcing a recount.

Activists push post-election audits

Among the experts and local activists consulted by the Stein campaign was Karen McKim, a coordinator for the Madison-based grassroots group Wisconsin Election Integrity, which focuses on the “appropriate use and management of election technology” to secure Wisconsin’s elections.

In the 2016 presidential race, McKim said she was was the first to catch the worst error made in Wisconsin. Even before the recount, she noticed that according to official numbers, roughly half of the 833 voters who cast ballots in the U.S. Senate race in the Oneida County community of Hazelhurst did not vote for president.

McKim reached out to the county clerk, asking whether there was a boycott. It turned out to be a human error; a poll worker was supposed to type in 484 votes for Trump, but accidentally typed the number 44. The outcome had already been certified in a countywide canvass. After McKim identified the mistake, the results were resubmitted.

Such an error, she said, “happens all the time.”

McKim has many such stories to tell. In 2014, hundreds of votes in a Stoughton municipal referendum were not initially counted, possibly because of “dust bunnies” that covered the optical scanners’ lenses. In Monroe, election officials lost 110 ballots cast in the state Senate Democratic primary of 2014.

A former Wisconsin Legislative Audit Bureau veteran, McKim not only identifies mistakes but seeks to correct them. Since 2012, she has been advocating post-election audits to verify the accuracy of election outcomes.

She favors a statistically based protocol known as a “risk-limiting audit” which involves counting a small sample of ballots. The procedure has been developed by election officials in collaboration with statisticians and security experts. It is recommended by the U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee and has become a requirement in Colorado, Rhode Island and Virginia. Ohio and Washington provide options for counties to run different types of audits, including these types of risk-limiting audits, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

In 2014, Wisconsin Election Integrity activists had a major victory, convincing the Government Accountability Board (now the Wisconsin Elections Commission) to change instructions clarifying county and municipal clerks’ right to verify the accuracy of the election outcomes. McKim said she is not aware of any clerks who have implemented this measure.

In 2016, McKim unsuccessfully ran for Dane County clerk. She did not expect to win, but used the campaign to raise awareness of post-election audits.

What have her efforts wrought? “Unanswered emails. Invitations to meetings unaccepted, even unacknowledged. Testimony at public meetings ignored,” McKim said.

Some officials skeptical audits needed

Wisconsin law already requires election officials to conduct voting equipment audits after general elections. The procedure, however, does not verify the accuracy of election outcomes, only whether the machines functioned properly. But that could change.

Wisconsin Elections Commission interim administrator Meagan Wolfe said her staff recently observed Colorado’s risk-limiting audit process. She said the agency is looking for ways to implement such audits consistent with existing law. The measure will be discussed at the next Commission meeting on Sept. 25, Wolfe said.

Barry Burden, the UW professor, said it likely will take a change in state law to require clerks to do post-election audits.

“If policymakers in the Legislature think that this security element is a good idea, they could pass a law pretty quickly, using models from other states, like Colorado, to implement it here,” he said.

Although Scott McDonell agrees risk-limiting post-election audits are probably a good idea, he does not plan to implement the measure anytime soon. He is confident in the integrity of Dane County’s system, noting that software that tallies the votes and programs the machine to read the ballots “are not connected to the internet.”

Said McDonell: “I’d say we’re safe.”

McDonell also said any significant change in how Dane County votes would be immediately obvious to him. “I know how every ward votes. You going to have Willy Street vote Republican? I mean …” McDonell smiled, naming one of Madison’s most liberal neighborhoods.

Like McDonell, the majority of municipal clerks are not particularly worried about hacking, said Barbara Goeckner, president of the Wisconsin Municipal Clerks Association.

“I know that the [Wisconsin Elections Commission] is overseeing election security in the equipment we use, the processes of the conducting of our elections and how our equipment is tested and certified,” said Goeckner, adding that the diversity of Wisconsin’s election systems is the best security check.

Goeckner added that conducting post-election audits is burdensome and expensive.

“To do those audits before certification is really difficult,” she said. “The difficulty lies in the timeline to complete the audits. Elections are not the only duties clerks have to complete. However, they take up a great deal of our time while we are preparing, conducting and finalizing them afterward.”

One advantage Wisconsin has over some other states: Paper ballots. No matter what kind of machine is used at a polling station, there is also a paper ballot produced for every vote cast.

But in interviews with the Center, leading national experts said that keeping the paper trail is not enough. They said robust post-election risk-limiting audits are a crucial tool to ensure accurate results.

“That’s the reason why you have paper — it shouldn’t be for show,” said Lawrence Norden, the deputy director of the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law. “There’s no question Wisconsin doesn’t do the kind of audits it should be doing.”

Hackers pierce veil of security

In April, J. Alex Halderman staged a demonstration on how to hack AccuVote TS and TSX touch-screen voting machines. Machines breached in Halderman’s experiment were in use in 2016 in municipalities in about half of the states, including Wisconsin. As of Jan. 1 of 2018, municipalities in the following Wisconsin counties were using AccuVote TSX machines for voters with disabilities: Calumet, Manitowoc, Walworth and Waushara counties.

In the demonstration, University of Michigan students were asked to pick the better school in a race with two candidates — Michigan itself and The Ohio State University. From his office computer, Halderman remotely altered the tally, making Ohio State the winner in a race where the majority of voters picked Michigan.

Vulnerabilities in other types of voting machines were demonstrated in the Voting Machine Hacking Village at DEFCON’s 2017 gathering. The co-founder of the village is Jake Braun, former director of White House and public liaison for the Department of Homeland Security. Braun, who is also a strategic advisor to DHS and the Pentagon on cybersecurity, wanted to draw lawmakers’ attention to vulnerabilities in the national election infrastructure.

During the event, more than 25 voting machines and electronic poll books were breached. Some of them had default usernames and passwords, such as “admin” and “abcde,” while others turned out to have internal parts manufactured in China, which could be designed to be vulnerable to manipulation, according to the DEFCON report.

While all the voting systems hacked by DEFCON participants and Halderman operate on touch-screen machines, experts also question the assertion that optical scanners, which are in wide use in Wisconsin, are unhackable.

A New York Times Magazine report published in February 2018 explored the ways those machines can be subject to attack, even when not connected to the internet. It cited the case of a machine in Pennsylvania’s Venango County that was miscounting votes

Although the machine was offline, officials found it had remote-access software, which allowed a county contractor to work on the machine remotely — but also made it vulnerable to hacking from someone else. (The miscounting turned out to be a “simple calibration error,” the magazine reported.)

Like that county, some Wisconsin counties outsource pre-election programming to equipment vendors — private companies whose operations are not regulated by any federal standards. It is unclear how widespread the practice is in Wisconsin.

“The [Wisconsin Elections Commission] does not currently track which, or how many, counties, program their equipment in-house or by using a vendor,” Meagan Wolfe said.

According to a leaked National Security Agency report published by The Intercept, an unnamed U.S. voting software supplier was the target of a cyberattack conducted by the Main Directorate of the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces, better known as the GRU, the intelligence agency whose 12 officers were recently indicted as part of the Mueller investigation.

Summarizing the leaked report, The Intercept reported, “Russian military intelligence executed a cyberattack on at least one U.S. voting software supplier and sent spear-phishing emails to more than 100 local election officials just days before last November’s presidential election.”

Wisconsin, Congress take some action

In March 2017, Wisconsin Democratic U.S. Rep. Mark Pocan introduced the Secure America’s Future Elections Act (H.R. 1562) that, among other things, would require routine audits of election outcomes. Since then, the bill gained 22 cosponsors but has not gotten out of committee.

This March, Congress passed a bipartisan measure allocating $380 million to boost election systems security in all 50 states. Wisconsin received $7 million.

Wisconsin’s grant will support six full-time election and cybersecurity positions at the Wisconsin Elections Commission. The commission also plans to strengthen WisVote, the statewide voter registration system, and conduct election security trainings for local officials.

Meagan Wolfe said all of the resources, including the six security-related positions, will be in place by the November election.

Despite this, Karen McKim said she plans to keep pushing for the audits.

“What gives me the energy to keep going through over six years is because it is so easily fixed,” McKim said. “All they have to do is unseal those bags and count votes in public and prove that the voting machines are working right. But they don’t. I just keep thinking that next month, all the election officials are going wake up and say, ‘Oh, we can do this.’ And they don’t.”

Grigor Atanesian, a native of St. Petersburg, Russia, is an Edmund S. Muskie fellow at the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism. He studies investigative reporting at the University of Missouri School of Journalism via a Fulbright grant. The nonprofit Center collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates. The Center’s coverage of democracy issues is supported by The Joyce Foundation.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us